Vagrancy

Thomas Rowlandson, Arrest of a Woman at Night, c.1800. The Courtauld Institute of Art, D.1952.RW.3338. © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Thomas Rowlandson, Arrest of a Woman at Night, c.1800. The Courtauld Institute of Art, D.1952.RW.3338. © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Introduction

The eighteenth century inherited from the sixteenth and seventeenth a body of statute law that saw in vagrancy and vagabondage a powerful social threat deserving of serious punishment, and a category of offence that was distinct from the issue of settled poverty. As the system of legal pauper settlement evolved between the 1660s and the 1690s the obvious distinctions between vicious vagrancy and deserving poverty, however, became increasingly difficult to delineate. Two separate systems were retained throughout the eighteenth century, but their workings, and the experience of the poor within them, became ever more similar. Gradually, vagrants came to be punished less often, while the development of passes allowing the poor to travel unhindered (and to claim support from local constables and overseers along the way), ensured that little of the brutality evident in sixteenth-century vagrancy legislation can be found by 1690. Many examples of vagrancy passes are filed among the Sessions Papers (PS).1

The legal framework for the prosecution and removal of vagrants evolved incrementally over the course of the period covered by this website, with some twenty-eight different pieces of legislation passed between 1700 and 1824. Of these Acts of Parliament, the most significant was the Vagrant Removal Costs Act of 1700, which shifted the expense of removing vagrants from the parish to the county (or the city in the case of the City of London).2 Although in no way the intention of the law makers, this legislation effectively encouraged parishes to redefine paupers as vagrants, as a means of transferring the costs of their support and removal to the county. This change also ensured that vagrancy policy - in terms of punishment and removal - came to form a significant part of the business of the Middlesex Bench and the Common Council and Lord Mayor of the City of London.

After the Vagrants Removal Costs Act, a range of further Acts of Parliament were mostly directed at codifying and consolidating the law, rather than fundamentally changing policy. In particular, the 1714 Vagrancy Act consolidated current legislation, and widened the definition of a vagrant.3 It bundled together in this single category settled paupers who were thought in danger of deserting their wives and children, those who refused to work for the usual wages, those wandering abroad and begging, a wider set of travelling mendicants and traders, and all those who were unable (for whatever reason) to give a good account of themselves.

This 1714 Act was in its turn superseded by 1744 Vagrancy Act, which again added little that was new to the then current legislation, but provided the legal framework for the policing and punishing of vagrants until 1792.4 The 1780s also saw the passage of two further Acts reflecting explicitly metropolitan concerns. In 1783, individuals found in possession of either small arms or burglary implements were encompassed within the vagrancy acts, and in 1787 those running unlicensed lotteries and similar games of chance were also explicitly defined as vagrants.5

Who were Vagrants?

Following a centuries-old tradition of associating vagrants with a series of specific occupations and activities, the 1744 Vagrancy Act simply listed who could be prosecuted under the law. The list was a long one that owed as much to tradition as to eighteenth-century occupational categories, and included:

- Patent gatherers, gatherers of alms under pretence of loss by fire, or other casualty

- Collectors for prisons, goals, or hospitals

- Fencers and bear wards (those who travel with a bear or dancing bear)

- Common players of interludes

- All persons concerned with performing interludes, tragedies, comedies, operas, plays, farces or other entertainments for the stage, not being authorized by law

- Minstrels and jugglers

- Persons pretending to be Gypsies, or wandering in the habit of Gypsies

- Those pretending to have skill in physiognomy, palmistry, or fortune telling

- Those using subtle crafts to deceive and impose, or playing or betting on unlawful games

- All persons who run away and leave their wives and children

- Petty chapmen and pedlars, not duly licensed

- All persons wandering abroad and lodging in alehouses, barns, outhouses or in the open air, not giving a good account of themselves

- All persons wandering abroad and begging, pretending to be soldiers, mariners, seafaring men, pretending to go to work in harvest

- All persons wandering abroad and begging

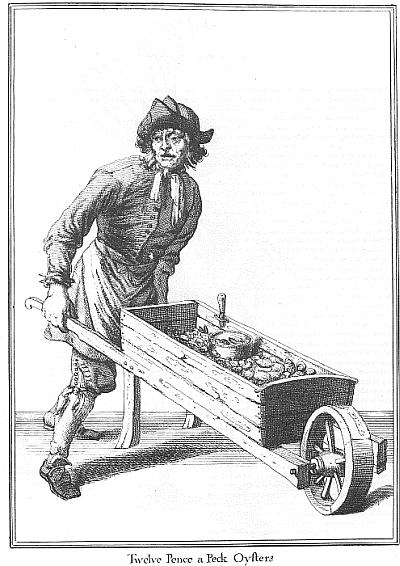

Twelve Pence a Peck Oysters, Marcellus Laroon, The Cryes of London, 1679. © London Lives.

Twelve Pence a Peck Oysters, Marcellus Laroon, The Cryes of London, 1679. © London Lives.

There is little evidence that strolling players and Gypsies were prosecuted with any regularity under the Vagrancy Acts, but prostitutes, seasonal workers, street pedlars and aggressive beggars certainly were. The inclusion of a separate provision for the punishment of individuals who simply threatened to desert their families, also ensured that almost anyone lacking property or position might be prosecuted under the title of a vagrant.

Of a sample of the first 175 individuals removed from Middlesex in the last three weeks of January 1786, for instance, 43% (75) were women, 44% (77) men and 13% (23) children travelling with their parents. This is reasonably close to the mix of gender and family organisation found in contemporary workhouses, and suggests that for the most part vagrants were paupers under another name. In this small sample there were fourteen complete families, and a further ten single women travelling with one or more children. The vast majority came from England, and approximately 25 per cent came from Middlesex and London.

Some paupers actively sought arrest as a way of supporting a journey home at the end of the season. A special case was made for soldiers and sailors returning from military service. They had always been explicitly exempt from the charge of vagrancy, and were directed to carry a letter from their commanding officer, or later from a magistrate, specifying their destination and the amount of time they an expected to be on the road. As the British military expanded, and as the use of settlement certificates increased, the ability to distinguish legitimate and military travellers (and their families) from vagrants grew more difficult.6

Up until the early 1780s, the numbers passed through Middlesex (including most vagrants removed from the City of London) ran from several hundred a year to somewhere over a thousand. According to Nicholas Rogers, in the first five years of the 1760s the average number of individuals removed ran to just over 750 per year.7 From the early 1780s, however, the scale of removals, particular from the City of London, began to rise substantially, as did the costs. In a petition in 1784 for an increase in his monthly stipend, the vagrant contractor for Middlesex, Henry Adams, claimed to have transported on average 1,245 vagrants per year (on the legal basis of 860 passes) between 1774 and 1777, and that this had risen to an average of 1,982 people a year by the first half of the 1780s.

Policing

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1786, MJ/SP/1786/04, LL ref: LMSMPS508090276.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1786, MJ/SP/1786/04, LL ref: LMSMPS508090276.

Policing vagrancy - or more accurately arresting aggressive beggars and prostitutes - was the responsibility in the City of London of City Marshal, who worked through the wards to direct the constables and nightwatchmen; and in Middlesex fell to the beadles and constables directly. From 1662 a reward of two shillings per arrest was offered. This was raised by the 1744 Act to five shillings for the arrest of the idle and disorderly, and ten shillings for wandering rogues or vagabonds actually brought to punishment. The impact of these rewards was muted, however, as they were granted at the discretion of the committing Justice of the Peace. In Middlesex, and through most of the century, they were awarded in only 20 per cent of cases. The level of policing was also effected by the attitude of the wider populace, who frequently supported beggars and prostitutes against constables and watchmen.8

Magistrates and the Lord Mayors of London regularly sought to use privy searches and general warrants to enforce the provisions of the vagrancy acts in spasmodic purges of the streets of London. Changing policy towards vagrants and evidence of irregular attempts to more comprehensively enforce the laws against vagrancy can be found in the Justices' Orders of the Court (GO). These purges occasionally led to tragedy, and never had the full support of the broader populace. On 15 July 1742, for instance, Thomas De Veil organised a general search for vagrants in Westminster that resulted in the arrest of twenty-four female beggars and prostitutes, six of whom subsequently died as a result of overcrowding in the holding cell of the watchhouse belonging to St Martin in the Fields. The watchhouse keeper, William Bird, was eventually found guilty at the Old Bailey of their murder by wilful neglect, reflecting the growing popular distaste for the targeting of beggars whose poverty was self-evident.9

On arrest vagrants were taken to a Justice of the Peace where they were examined. Like a pauper examination (EP) (and unlike a bastardy examination, which was more formal and required the presence of two Justices), a vagrancy exam was primarily intended to establish the settlement of the examinee. In most instances, the vagrant was simply passed to their place of settlement after a brief stay at a house of correction; the examination itself being passed to the clerk of sessions. The full punishment available under the law was imposed in only a small minority of cases.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Examinations Book, 1741-1742, B1169, LL ref: WCCDEP358180040.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Examinations Book, 1741-1742, B1169, LL ref: WCCDEP358180040.

Punishments

Besides listing the categories of people who might fall within the definition of a vagrant, the 1713 and 1744 Acts divided vagrants into three broad classifications:

- Idle and Disorderly Persons

- Rogues and Vagabonds

- Incorrigible Rogues

A different punishment was specified for each. For the Idle and Disorderly, essentially the settled but unruly poor, a period of hard labour for up to one month in a house of correction was specified. For Rogues and Vagabonds, all the bear wards and minstrels, strolling players and jugglers listed in the Act, a public whipping followed by incarceration in a house of correction was mandated. These vagrants were also subject to a further examination at the next meeting of sessions, at which time they might be imprisoned and set to hard labour for a further six months. At the completion of their sentence rogues and vagabonds were either removed to their place of settlement by a pass, or if male and above twelve years old, sent to the army or navy.

When presented at sessions, rogues and vagabonds could be re-classified as Incorrigible Rogues (primarily persistent and well-known offenders), and sentenced to between six months and two years further imprisonment and hard labour, and a further round of whippings. And if, having been condemned as an incorrigible rogue, the prisoner escaped, they could be transported for seven years.10

In practice the imposition of these punishments was markedly random. Local beggars and prostitutes, the idle and disorderly, were frequently sentenced to longer periods of hard labour than were the unknown and travelling poor, rogues and vagabonds. By contrast, these travelling vagrants were frequently passed to their place of settlement without further punishment. Whipping was restricted to a small number of cases. From 1744 provision was also made to allow a vagrant's bundle to be searched, and for their money or goods to be confiscated in order to defray the costs of their removal.11 This provision was honoured primarily in the breach.

Vagrant Contractors

Detail: A Scene in Bridewell, plate IV. William Hogarth, A Harlot's Progress, April 1732. © Tim Hitchcock.

Detail: A Scene in Bridewell, plate IV. William Hogarth, A Harlot's Progress, April 1732. © Tim Hitchcock.

Because the removal of vagrants fell to the county after 1700, there gradually developed a sophisticated system of contracting out the task of transportation out of the county. In Middlesex up until 1757, vagrants were passed directly by parish constables, who then claimed a mileage allowance, but from that date, and for the rest of the century Middlesex employed a contractor (first James Sturges Adams and then his son Henry) to clear the houses of correction of vagrants several times a week, and transport them to the county boundary. The details of this arrangement were laid out in the contract entered into by James Sturgis Adams in 1757. Adams was charged to collect vagrants twice a week from the houses of correction at Clerkenwell and Tothill Fields, alternating between collecting those going north, and those heading south. He was to provide a covered cart and horses, and was allowed six pence a day per vagrant for their subsistence, and ten pounds a month for his trouble.12

Adams, succeeded in 1774 by his son Henry, maintained a large establishment at Islington where vagrants stayed a couple of days before being carted to the county boundary at Staines, Colnbrook, Mimms or Enfield, depending on their direction of travel. Once there, they were handed over to the contractor for the next county to be speeded on their way.

As a part of this same contract, Adams and his successors were obliged to deliver a:

Numerous quarterly accounts of this sort, detailing the names and settlements of vagrants can be found among the Sessions Papers (PS) reproduced on this site.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1785, MJ/SP/1785/01, LL ref: LMSMPS507920077.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1785, MJ/SP/1785/01, LL ref: LMSMPS507920077.

The Crisis of the 1780s

The impact of the system of punishment and removal of vagrants is difficult to assess. Up until the 1780s the implementation of the provisions of the Vagrancy Acts was haphazard and subject to periodic bursts of carceral enthusiasm. The rise of the use of more informal passes (and friendly passes in London and Middlesex), meant that the number of individuals effected, and the role of the system in the poor's economies of makeshift, is impossible to determine. But from the early 1780s the system came under increasing pressure, and was eventually forced to change.

In 1787 the Middlesex Bench created a committee to investigate why the cost of passing vagrants through the county had risen substantially in recent years. Henry Adams, the vagrant contractor for Middlesex at the time, reported that the cause was the large number of vagrants being issued passes from the City of London and transferred on through Middlesex, in combination with the large number of such vagrants who were ill and required medical attention. In the same report Adams claimed to have passed 7,539 vagrants in the twelve months from October 1784, of whom 4,185 originated in the City of London (compared to 3,354 vagrants apprehended in Middlesex or passed from other parts of the country).

In the City of London during the same years the cost of referring vagrants from Bridewell to the Hospitals of St Bartholomew's and St Thomas's began to rise substantially. By the early 1790s, the cost of clothing and supporting vagrants in these hospitals amounted to almost £1,800 a year, forcing the prison committee of Bridewell to beg the Lord Mayor to address the problem.13

A reflection of this same situation can also be found in the Admissions Registers (RH) of the hospitals themselves. In 1790 at St Thomas's Hospital the registers record some 228 patients paid for by the City, overwhelmingly vagrants transferred from Bridewell; while by 1795 the Governors of Bridewell were complaining bitterly that the City magistrates were sending:

This substantial rise in the number of vagrants prosecuted and removed in part reflects a growing intolerance of urban disorder following the Gordon Riots, but it also reflects the increasingly instrumental use of the system by the poor in order to access transportation, subsistence and medical care. It was the pressures of numbers and of costs (which were not unique to London) that helped motivate the creation of the Proclamation Society and the convening of a unique Magistrates' convention in 1790. It was also these same pressures that contributed to the passage of the 1792 Middlesex Justices Act, and the 1792 Vagrancy Act.14 Both of these Acts sought to regularise the system of police and the treatment of offenders, and to ensure that punishment for vagrancy was uniformly imposed.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Passroom at Bridewell, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Passroom at Bridewell, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keyword Vagrant:

Introductory Reading

- Beattie, John. Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror. Oxford, 2001.

- Eccles, Audrey. The Adams' Father and Son, Vagrant Contractors to Middlesex 1754-94. Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 57 (2006), pp. 83-91.

- Hitchcock, Tim. "You bitches... die and be damned": Gender, Authority and the Mob in St Martin's Round-House Disaster of 1742. In Hitchcock, Tim, and Shore, Heather, eds, The Streets of London: From the Great Fire to the Great Stink. 2003, pp. 69-81, 224-7.

- Innes, Joanna. Inferior Politics: Social Problems and Social Policies in Eighteenth-Century England. Oxford, 2009.

- Rogers, Nicholas. Policing the Poor in Eighteenth-Century London: The Vagrancy Laws and Their Administration. Histoire sociale / Social History, 24 (1991), pp. 127-47.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 For the now classic work on the evolution of the laws against vagrancy in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, see A.L. Beier, Masterless Men: The Vagrancy Problem in England, 1560-1640 (1985). ⇑

2 11 William III c. 18. ⇑

3 13 Anne c. 26. ⇑

4 17 George II c. 5. ⇑

5 23 George III c. 88; and 27 George III c. 11. For a discussion of the 1787 Act see Audrey Eccles, A Superior Kind of Vagrant: Middlesex Lottery Vagrants in the 1790s, Transactions of the London and Middlesex Archaeological Society, 60 (2008), pp. 213-220. ⇑

6 Tim Hitchcock, Down and Out in Eighteenth-Century London (2004), ch. 7. ⇑

7 Nicholas Rogers, Policing the Poor in Eighteenth-Century London: The Vagrancy Laws and Their Administration, Histoire Sociale / Social History, 24 (1991), pp. 127-47. ⇑

8 John Beattie, Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror (Oxford, 2001), pp. 153-5. ⇑

9 Tim Hitchcock, "You bitches ... die and be damned": Gender, Authority and the Mob in St Martin's Round-House Disaster of 1742, in Tim Hitchcock and Heather Shore, eds, The Streets of London: From the Great Fire to the Great Stink (2003), pp. 69-81, 224-7. ⇑

10 Richard Burn, The Justice of the Peace and Parish Officer (1755), vol. 2, pp. 485-507. ⇑

11 Rogers, Policing the Poor. ⇑

12 Beatrice and Sidney Webb, English Local Government: English Poor Law History: Part 1. The Old Poor Law (1927), ch. 7. ⇑

13 Hitchcock, Down and Out, p. 178. ⇑

14 43 George III c. 61. ⇑