Bridewell Prison and Hospital

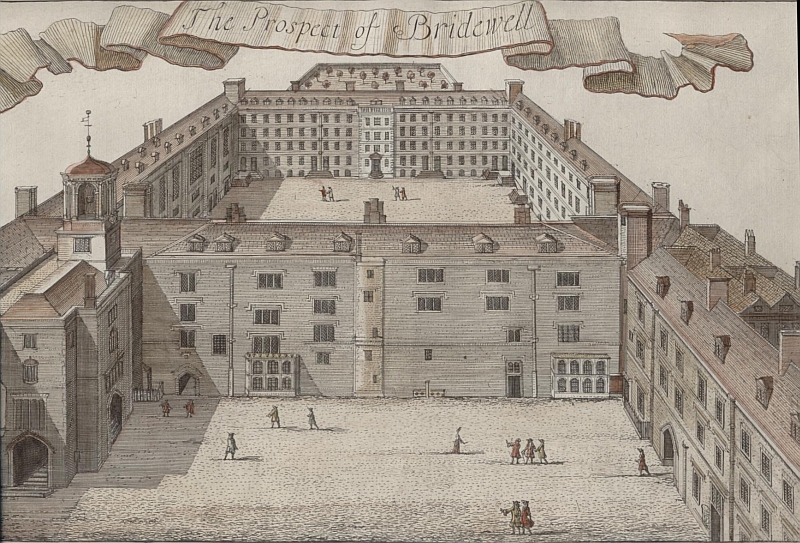

The Prospect of Bridewell from John Strype's, An Accurate Edition of Stow's Survey of London (1720). © Tim Hitchcock.

The Prospect of Bridewell from John Strype's, An Accurate Edition of Stow's Survey of London (1720). © Tim Hitchcock.

Introduction

Bridewell Prison and Hospital was established in a former royal palace in 1553 with two purposes: the punishment of the disorderly poor and housing of homeless children in the City of London. Located on the banks of the Fleet River in the City, it was both the first house of correction in the country and a major charitable institution (reflecting the early modern definition of a "hospital"). Its records provide valuable evidence of both petty crime and pauper apprenticeships in the eighteenth century.

Government

From the 1570s Bridewell was governed jointly with Bethlem Hospital (which treated the insane) by a Court of Governors. Because appointment as a governor was socially prestigious, and gave elite men the right to nominate apprentices, a large number of governors were appointed (there were 270 in 1700). Needless to say, only a small proportion showed up for meetings of the Court, and over the course of the eighteenth century the Court's business was increasingly devolved to committees, and the court met less frequently. As recorded in its Minutes (MG), the Court's business included determining the fate of prisoners and apprentices, the appointment of officers, and administering the hospital's properties and finances. One of the most important committees was the Prison Committee, whose Minutes (MB), and those of its sub-committee which met weekly, are included on this website.

Detail: A Scene in Bridewell, plate IV. William Hogarth, A Harlot's Progress, April 1732. © Tim Hitchcock.

Detail: A Scene in Bridewell, plate IV. William Hogarth, A Harlot's Progress, April 1732. © Tim Hitchcock.

From the 1770s, Bridewell became subject to increasing criticism from the City of London and prison reformers. As with other London prisons, reformers were concerned that prison life corrupted rather than reformed the prisoners, and the apprentices who mixed with them. There were suggestions that the apprentices might be better trained elsewhere, such as the London Workhouse, and that Bridewell should be turned solely into a disciplinary institution. Although the number of arts masters training the apprentices was reduced towards the end of the century, the apprentices remained until 1827.

Nonetheless, prison life was dramatically changed in the last two decades of the century, as Bridewell fell under the influence of the prison reform movement. A combination of improved conditions with more strict regimes made life different, if not necessarily better, for its inhabitants. Solitary confinement was introduced, and in 1792 the whipping of female prisoners was abolished. The same year, the prison sub-committee was established in order to carry out weekly inspections. In 1797, following the construction of a new wing, a new system of segregation and classification of inmates was introduced, and well-behaved women were invited to stay after their discharge from the prison while they waited until they found a place in service.

Apprentices

Bridewell hospital was established to provide a home and training for deserving children. Boys were referred by parishes, Christ's Hospital, and sessions, or they were nominated by the governors from the families of poor citizens. Unlike parish apprenticeships, those at Bridewell were considered highly desirable as their successful completion ensured both the freedom of the City of London and payment of a substantial charitable contribution (ten pounds, from the charity known as Lock's Gift) towards setting up as an independent master.

Bridewell and Bethlem, Minutes of the Court of Governors, 1713-22, 5 December 1718, Bridewell and Bethlem Archives, Ms. BCB-19 (Box C04/3), LL ref: BBBRMG202040401.

Bridewell and Bethlem, Minutes of the Court of Governors, 1713-22, 5 December 1718, Bridewell and Bethlem Archives, Ms. BCB-19 (Box C04/3), LL ref: BBBRMG202040401.

The boys were given a basic education (in 1675 a school master was appointed to teach them reading and writing), and, depending on the arts master to whom they were apprenticed, they were taught one of a number of trades, including weaving, shoemaking and glovemaking.

In the late seventeenth century, there were around 100 apprentices in the hospital, but reflecting the overall decline in apprenticeship in the eighteenth century, the numbers decreased over time: 132 in 1705, 74 in 1750, 26 in 1791. The concentration of such a large number of adolescents unsurprisingly led to numerous disciplinary problems, which were recorded in a separate Register (IA). There were also complaints that the masters were negligent and dissolute.

In addition to the register of disciplinary cases, the apprentices can be found in several other Bridewell records: Registers of Apprentices (RA), which list those indentured and the name and trade of the master, and the Court Minute Books (MG) and Committee Minute Books (MC), which include apprentices indentured and those made free on the completion of their service, and the governor's decisions on problem cases.

Prisoners

Petty offenders were committed to Bridewell by a number of City officers, including constables and magistrates, and even occasionally by parents and masters. Beadles were supposed to search their wards daily and bring any vagrants and idle persons to the prison. From 1785, however, only magistrates were allowed to make commitments.

As recorded in the Warrants of Commitment and Discharge (PM) and the Minutes of the Court of Governors (MG), those committed were accused of a very wide range of offences, including vice, vagrancy, and property crimes. In 1797 188 women were committed for prostitution, 43 women and 95 men were committed for "smaller acts of dishonesty", and 34 were disorderly apprentices. But by this time the vast majority of prisoners, 979, were vagrants "committed according to act of parliament".1 Although felons were supposed to be committed to Newgate and not Bridewell, in fact many inmates were accused of indictable property thefts. Between 1701 and 1760 all these offenders could also be sent to the Workhouse of the London Corporation of the Poor in Bishopsgate; it appears that the offenders from the eastern half of the City were normally sent to the London Workhouse, while those from the western half were sent to Bridewell.

The wide range of offences punishable in Bridewell meant that a very large number of offenders passed through its doors. Faramerz Dabhoiwala estimates that in most years there were at least nine or ten commitments per 1,000 inhabitants in the City. While there were significant annual fluctuations in the total number of prisoners, numbers peaked around 1700 (1,474 in 1702) during the first reformation of manners campaign. Commitments then declined gradually (but with periodic peaks during the crime panics of 1723, 1748-54 and 1762-63) to a low of 336 in 1764, followed by a gradual increase (with peaks during the economic difficulties of the late 1760s, the late 1770s when transportation was suspended, and the crime wave of 1783-84), to high levels from 1792, perhaps owing to worries about disorder prompted by events in France. The century ended with 1,989 commitments in 1800, but the highest total for the century came in 1784 (2,956), during the panic about crime which followed the end of the American War.2

The purpose of a house of correction was to punish and correct offenders, not merely hold them in incarceration. Most prisoners were therefore given punishments, which were determined by the governors. These were usually whipping and/or being put to hard labour, typically beating hemp. Whippings were notoriously carried out in front of the governors, and could be observed by others from a public gallery.

Conditions

Like other eighteenth-century prisons, Bridewell was initially an open prison, where different categories of offenders could intermingle and visitors could bring in money, food, gin, and other gifts. Men and women were kept separate, however. As we have seen, during the late eighteenth century increased segregation of prisoners and solitary confinement were introduced.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Passroom at Bridewell, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Passroom at Bridewell, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Prisons were notoriously unhealthy places, but as both a hospital and a prison, Bridewell was more advanced than any other eighteenth-century prison in providing medical care. It had a surgeon, physician and infirmaries, and the prisoners were regularly inspected for disease. The introduction of bathing tubs, straw bedding, and regular clothes-washing helped prevent the spread of disease. Such was the level of treatment and facilities available that it is possible that the poor used commitment to Bridewell as a means of accessing medical care.

When the prison reformer John Howard visited Bridewell in 1789 he praised the prison for its facilities:

While confinement in Bridewell was certainly no picnic, it is likely that the London poor viewed it more favourably than some of the other prisons in the metropolis. During the Gordon Riots in 1780, when several London prisons were burned to the ground, the mob only broke into Bridewell and released the prisoners, leaving the buildings intact. Nonetheless, it was customary for prisoners discharged from Bridewell to take the free loaf of bread given them upon their discharge and stick it on the railings outside the prison to show their contempt. It was, after all, a prison.

Documents Included on this Website

Introductory Reading

- Cowie, L. W. Bridewell, History Today, 23:5 (1973).

- Dabhoiwala, Faramerz. Summary Justice in Early Modern London. English Historical Review, 121 (2006), pp. 796-822.

- Griffiths, Paul. Lost Londons: Change, Crime and Control in the Capital City 1550-1660. Cambridge, 2008.

- Hinkle, William G. A History of Bridewell Prison, 1553-1700. Lampeter, 2006.

- O'Donoghue, E. G. Bridewell Hospital, Palace, Prison, Schools, Vol. 1 : From the Earliest Times to the End of the Reign of Elizabeth; Vol. 2: From the Death of Elizabeth to Modern Times. 1923-9.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 Thomas Bowen, Extracts from the Records and Court Books of Bridewell, p. 61. The parliamentary act was the 1792 Vagrancy Act (43 George III c. 61). ⇑

2 Faramerz Dabhoiwala, Summary Justice in Early Modern London, English Historical Review, 121 (2006), pp. 796-822. ⇑

3 John Howard, An Account of the Principal Lazarettos in Europe (Warrington, [1789]), p. 127. ⇑