The City of London

Antonio Canaletto. Old London Bridge. 1746-1768. British Museum, constable 738. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Antonio Canaletto. Old London Bridge. 1746-1768. British Museum, constable 738. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Introduction

Originally the principal settlement around which the rest of the metropolis grew, the City of London has been governed independently since 886. The square mile of its jurisdiction included not only the land within the medieval walls, but also a crescent of land outside the walls, known as the City without the walls. With its powerful City-wide authorities of the Lord Mayor and the Courts of Aldermen and Common Council, its overlapping local jurisdictions of wards and parishes, and the separate corporations of the guilds, the City was governed differently and more intensively than any other part of the metropolis. Throughout the century, the City successful defended its independence from all other forms of metropolitan government, as exemplified in its exemption from the 1792 Middlesex Justices Act.

At the turn of the eighteenth century no more than a quarter, and at the end of the century no more than a sixth, of Londoners lived in the City, but it continued to exercise a disproportionate influence over the metropolis, and British government and society more generally. This was particularly true in relation to the formation of criminal justice policy in the first half of the eighteenth century, when lobbying by City officials, worried about the apparently relentless rise in violent crime, was instrumental in convincing the government to introduce several pieces of innovative legislation, notably the Transportation Act of 1718, which for the first time introduced a substantial alternative punishment to hanging. In 1737, the Lord Mayor and Aldermen set up the first regular magistrates' court in the metropolis. In the second half of the century, however, as the City's power within the metropolis declined, the impetus for criminal justice reform shifted to Westminster, where Henry and John Fielding introduced innovative policing and judicial practices from their office on Bow Street.

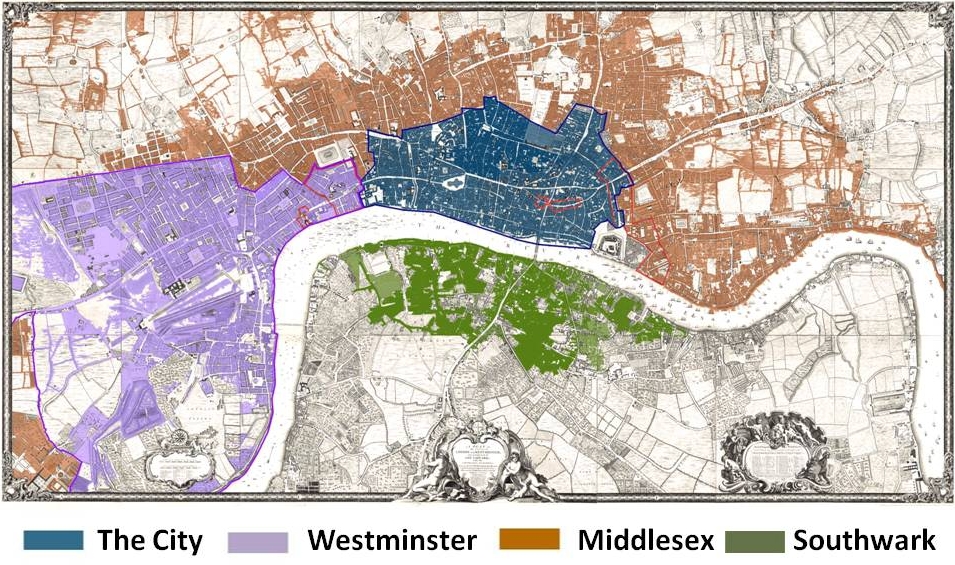

The City of London is indicated in dark blue, Westminster in purple, Middlesex in brown, and Southwark in green. The base map is John Rocque's, London, Westminster and Southwark, 1746. © Motco 2001 (base map only).

The City of London is indicated in dark blue, Westminster in purple, Middlesex in brown, and Southwark in green. The base map is John Rocque's, London, Westminster and Southwark, 1746. © Motco 2001 (base map only).

Having fully recovered from the devastating Great Fire of 1666, the City had between 125,000 and 150,000 inhabitants in the eighteenth century (128,000 in 1801), densely packed along its medieval streets. A mercantile and commercial centre, most people who worked in the City still lived there, though by the end of the century some of its wealthier citizens had moved out into the suburbs. Within the City walls, which were for the most part still standing, the population was predominantly wealthy and closely governed in small parishes, while the larger parishes outside the walls were populated primarily by craftsmen, labourers and the poor.

London Lives includes a full set of records of two City parishes, the wealthy inner City parish of St Dionis Backchurch and the poorer extra-mural parish of St Botolph Aldgate, part of which fell within the jurisdiction of the county of Middlesex.

Robert Neal Hind. A Study of an Alderman. 1855. British Museum, British Roy PVII. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Robert Neal Hind. A Study of an Alderman. 1855. British Museum, British Roy PVII. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Government

The City was governed by a Corporation, led by the Lord Mayor, with a Recorder, Court of Aldermen, Court of Common Council, and Common Hall. The Lord Mayor was chosen by the aldermen and served for a year. The Recorder was the City's chief legal officer, and often served as a judge at the Old Bailey. The Court of Aldermen was the upper house of City government, and met weekly to govern the City. Aldermen were required to possess at least £10,000 in property (£15,000 from 1710) and served for life. In contrast, the Court of Common Council, the lower house, consisted of more than 250 members and only met when summoned by the Lord Mayor. The Court of Common Council had the power to pass by-laws regulating City life, including the night watch, but the Court of Aldermen, who also sat on Common Council, had the power to vet the agendas for their meetings, and claimed the power to veto their resolutions. Both the Court of Aldermen and the Court of Common Council were elected by the freemen of the City, householders who paid at least £10 a year in rent, and 30 shillings a year in taxes. Most freemen acquired this status through their membership of a guild. Common Hall, an assembly of several thousand guild freemen, had the power express a preference for the choice of Lord Mayor, elect one of the City's two Sheriffs, and choose the City's Common Councilmen and its four Members of Parliament.

While the City's government was thus strongly hierarchical in structure, it was also highly participatory, with a large proportion of the householders being able to participate in the selection of local officers. This meant that public concerns about social problems could be directly channelled to the officers who had the responsibility for dealing with them.

Wards and Parishes

The City was divided into twenty-six wards, each of which elected an alderman. Each ward was divided into precincts, whose householders met once a year to nominate one or more constables for the ensuing year; there were 240 precincts in total. In turn, all the householders in each ward met once a year at the wardmote, when officers were appointed and an inquest jury was named, with the duty of surveying the ward and reporting any wrongs to the Court of Aldermen. Day to day government of each ward was carried out by the common council of the ward, composed of the alderman, deputy aldermen, and common councilmen. Wards had the responsibility for policing the City, and their officers were responsible for introducing some important innovations in the eighteenth century.

Robert Neal Hind, Study of a Common Councilman. 1855. British Museum, British Roy PVII. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Robert Neal Hind, Study of a Common Councilman. 1855. British Museum, British Roy PVII. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The City was also divided, like the rest of the country, into parishes, a unit of church governance which also regulated the distribution of poor relief. The boundaries between parishes and wards in the City were rarely the same, with many parishes sitting in more than one ward. There were 108 parishes in the City, ranging widely in size and wealth. Central parishes such as St Dionis Backchurch consisted of only a handful of streets and a population under a thousand, while parishes outside the City Walls, such as St Botolph Aldgate, were much larger and poorer, with populations well over 10,000. Under orders from the Court of Aldermen, these poorer parishes regularly received financial aid from the wealthier inner city parishes in order to meet their poor relief costs. As with the Middlesex parishes, City parishes each had churchwardens and overseers of the poor, and were governed by a vestry. Some parishes, including St Botolph Aldgate, extended beyond the City's jurisdiction into Middlesex, making parochial government particularly complicated.

Magistrates

In the early eighteenth century, the Justices of the Peace for the City were selected from the Court of Aldermen, and included the Lord Mayor, the Recorder (the chief legal officer in the City), and senior aldermen. In 1741, however, the growing unwillingness of aldermen to serve in this role meant that all aldermen were automatically appointed as magistrates. As in Middlesex, City magistrates held sessions of the peace eight times a year, for hearing misdemeanor criminal prosecutions and other business. More serious criminal trials were held at the Old Bailey, where the Lord Mayor, Recorder, and aldermen sat as judges alongside those from the high courts at Westminster.

For the work of the Lord Mayor and Justices hearing criminal accusations outside sessions, and the formation of City magistrate's courts for the conduct of such business in 1737, see Justices of the Peace and the Pre-Trial Process.

Guilds

Although their role in regulating economic activities was in decline, guilds continued to play an important role in the political life of the City, as is evident in the fact liverymen had voting rights in Common Hall, and in the City's social life, through regular dinners and the distribution of charity. See the separate page on this subject.

Introductory Reading

- Beattie, J. M. London Crime and the Making of the "Bloody Code", 1689-1718. In Davison, L. et al, eds, Stilling the Grumbling Hive. Stroud, 1992.

- Beattie, J. M. Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror. Oxford, 2001.

- Harris, Andrew T. Policing the City: Crime and Legal Authority in London, 1780-1840. Columbus, Ohio, 2004.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography