Houses of Correction

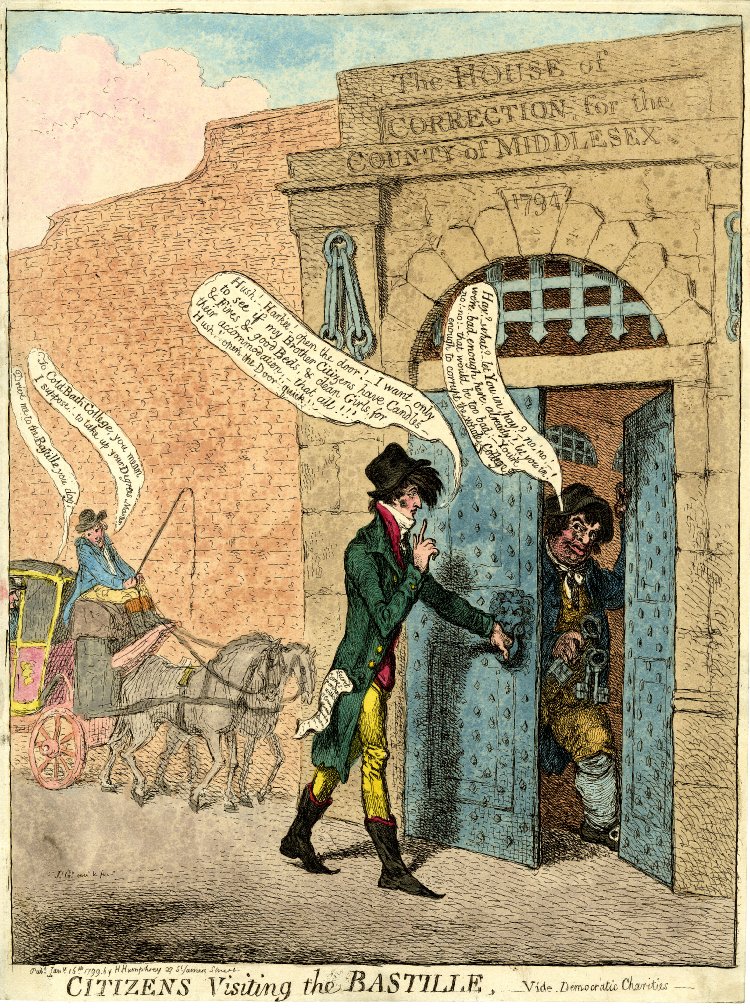

James Gilray. Citizens Visiting the Bastille. 1799. British Museum, Satires 9341. © Trustees of the British Museum.

James Gilray. Citizens Visiting the Bastille. 1799. British Museum, Satires 9341. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Introduction

Houses of correction were established in the late sixteenth century as places for the punishment and reform of the poor convicted of petty offences through hard labour. London contained the first house of correction, Bridewell, and the Middlesex and Westminster houses opened in the early seventeenth century. As reflected in the first reformation of manners campaign, the late seventeenth century witnessed renewed interest in reforming offenders in this way, and resulted in the growth in the number of houses established and the passage of numerous statutes prescribing houses of correction as the punishment for specific minor offences including vagrancy. In London, these developments led to a significant growth in the number of commitments to its four houses of correction.

During the eighteenth century houses of correction, which were often generically termed bridewells, evolved in response to increased legal scrutiny of the basis of commitments. The number of prisoners did not decline, but the types of people imprisoned changed. Like other prisons, in the last quarter of the century they were effected by the prison reform movement.

Offences and Punishments

Except in the City, where beadles could also make commitments, offenders were typically committed to houses of correction by Justices of the Peace, who used their powers of summary jurisdiction to order immediate punishment for those accused of minor offences. In the Middlesex and Westminster houses of correction in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries the most common charges against prisoners were prostitution, petty theft, and "loose, idle and disorderly conduct" (a loosely defined offence which could involve a wide range of misbehaviour). Some of these offences, particularly the thefts, were actually indictable as felonies, but plaintiffs and Justices of the Peace appear to have preferred the quick justice of a summary conviction and stint in a house of correction to more formal judicial procedures. In addition, a small number of prisoners were simply committed because they were unable to find sureties to guarantee their appearance at Sessions.

Reflecting the fact that most of these offences were victimless, in the sense that no specific individual could be identified as the victim, the plaintiffs behind these commitments were primarily official, especially night watchmen and constables, and informers attached to the reformation of manners campaign. Other plaintiffs included the victims of theft and the parents and masters of disorderly children and apprentices. Over two-thirds of the prisoners were female, and although information about prisoners' backgrounds is limited, most appear to have been poor, single, and recent migrants to London.

Virtually all the prisoners were put to hard labour, typically beating hemp. In addition, over half were whipped, particularly those deemed guilty of theft, vagrancy, and lewd conduct and nightwalking (prostitution). More than half of offenders were released within a week of their commitment, and two-thirds within two weeks. For the most part, punishment in houses of correction took the form of a short, sharp shock.1

The character of commitments to London's houses of correction changed in the eighteenth century, however, as they were subjected to increasing legal scrutiny. The number of prisoners committed for idle and disorderly conduct and street walking declined as Justices began to charge prisoners with a wider range of more specific offences. At the same time, a much larger number of offenders, including felons, were simply committed for safekeeping until their trials. In 1720 an act allowed the use of houses of corrections for purely custodial detention of "vagrants, and other criminals, offenders, and persons charged with small offences".2 By the 1760s and 1770s, prisoners awaiting trial accounted for more than three-quarters of those committed to the Middlesex and Westminster houses.3

By the late eighteenth century, bridewells were used increasingly like prisons, both as a place to hold those awaiting trials and as a place of punishment for those convicted. Between 1706 and 1718, an attempt was made to make imprisonment in houses of correction a punishment for convicted felons, but this failed. In response to the collapse of transportation in 1776, the act which led to the creation of the hulks once again authorised the use of houses of correction for the punishment convicted felons at hard labour, as did the 1779 Penitentiary Act.4

Like most prisons, conditions in houses of correction depended on whether a prisoner could afford to pay for luxuries and better treatment. Most prisoners were poor, and dependent on the "kindnesses of the keeper" and charity provided by prison visitors. Referring to the Middlesex House of Correction in Clerkenwell, in 1757 Jacob Ilive complained that:

Detail: A Scene in Bridewell, plate IV. William Hogarth, A Harlot's Progress, April 1732. © Tim Hitchcock.

Detail: A Scene in Bridewell, plate IV. William Hogarth, A Harlot's Progress, April 1732. © Tim Hitchcock.

In 1780s and 1790s, however, houses of correction fell under the influence of the prison reform movement. A 1782 act required county sessions to appoint Justices of the Peace to inspect houses of correction and ensure hard labour was provided, and in the same year Gilbert's Act provided measures for raising money for the reconstruction of houses of correction.6 In London, Bridewell was an early adopter, providing improved conditions for prisoners along with segregation of prisoners, solitary confinement, and regular inspections.

The opening of Cold Bath Fields in Middlesex in 1794 exemplifies all these trends: both a house of correction and a prison, it provided solitary confinement as well as an infirmary, religious instruction, and employment.

Prisoners and the Evolution of Houses of Correction

It is likely that most poor offenders had little control over whether they were committed to a house of correction. But the fact that Henry Fielding described houses of correction as "schools of vice" and "seminaries of idleness",7 suggests that bridewells may have been preferred by the poor to other prisons, where prisoners were forced to stay much longer, possibly with less charity, awaiting trials. Given the discretion exercised by plaintiffs and Justices of the Peace over how to prosecute many offences, it is possible that some of the accused were able to convince their prosecutors that a short (if painful) stint in a house of correction would be preferable to a longer stay in prison awaiting a formal trial, with all the additional costs that would place on the prosecutor. In this sense, a preference for this form of punishment over the traditional prison may have contributed to the continued use of incarceration in bridewell even in the face of repeated criticisms and legal obstacles. In the longer term prisons eventually became more like houses of correction rather than the reverse.

In addition, and paradoxically, complaints by prisoners and others about overcrowding, disease, and mistreatment by keepers in houses of correction generated pressure which contributed to the reforms implemented in the late eighteenth century, including improved bedding and medical care and the introduction of regular inspections.

London Houses of Correction

City of London

See Bridewell

Clerkenwell

The Middlesex house of correction was originally built in 1616, and was rebuilt in 1774-75. It held many more prisoners than New Prison, the county prison intended to hold prisoners awaiting trial in Middlesex. This house of correction often contained more than one hundred prisoners at a time, and numbers increased with the inclusion of prisoners sentenced to hard labour following the suspension of transportation in 1776. John Howard found 171 prisoners when he visited it in 1779. Unsurprisingly, it proved difficult to prevent escapes, and there was a mass escape in 1782. In 1794, it was replaced by Cold Bath Fields.

Surrey

In 1770 this house of correction, in Southwark, was presented by the Surrey grand jury as "too small, unhealthy and unsafe".8 Two years later the decision was taken to build a new building, owing to "population growth and the need for more suitable prison accommodation".9 The following year the new building, on St George's Fields, opened, with separate wards for men, women, and children. Nonetheless, when John Howard visited the prison in 1776 and found twenty-nine prisoners, he criticised it for having dirty rooms (there were chickens in two or three of them) and no infirmary. Several sick prisoners were on the floor without any bedding or straw provided and there was no work for the prisoners.10 In 1780 the building was destroyed in the Gordon Riots; and when it was rebuilt wards were added for the correction of incorrigible rogues.

Tothill Fields, Westminster

Built in 1618 and enlarged in 1655, there was a tablet above the gateway stating "Here are several sorts of work for the poor of this parish of St Margaret's Westminster. As also this county according to law and for such as will beg and live idle in the said City and Liberty of Westminster." In 1776 it took on the function of a gaol when the nearby Gatehouse Prison closed. When John Howard visited the prison in 1777 he found 110 prisoners accommodated in three day rooms and seven night rooms, plus five small rooms for "faulty apprentices". While he praised the night rooms for being "constantly washed" and "quite wholesome", he noted that there was not enough space for the prisoners. Although there was no infirmary, there was "a little room used as a surgery".11 Even this prison, however, was touched by the reform movement; and a sick ward was incorporated by the end of the century.

Introductory Reading

- Innes, J. Prisons for the Poor: English Bridewells, 1555-1800. In Snyder, F. and Hay, D. eds, Labour, Law and Crime: An Historical Perspective. 1987, pp. 42-122.

- Shoemaker, Robert B. Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex. Cambridge, 1991, chap. 7.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 Robert B. Shoemaker, Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex (Cambridge, 1991), chap. 7. ⇑

2 6 George I c. 9. ⇑

3 Joanna Innes, Prisons for the Poor: English Bridewells, 1555-1800, in F. Snyder and D. Hay, eds, Labour, Law and Crime: An Historical Perspective (1987), p. 95. ⇑

4 16 George III c. 43; 19 George III c. 74. ⇑

5 Jacob Ilive, Reasons Offered for the Reformation of the House of Correction in Clerkenwell (1757), p. 33. ⇑

6 22 George III c. 64; 22 George III c. 83. ⇑

7 Henry Fielding, Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers (1751), p. 63. ⇑

8 Cited by C. W. Chalklin, The Reconstruction of London's Prisons 1770-99: An Aspect of the Growth of Georgian London, London Journal 9 (1983), p. 27. ⇑

9 Chalklin, Reconstruction of London's Prisons, p. 28. ⇑

10 John Howard, The State of the Prisons in England and Wales (Warrington, 1777), pp. 236-37. ⇑

11 Howard, State of the Prisons, pp. 193-94. ⇑