The Poor Law and Charity: An Overview

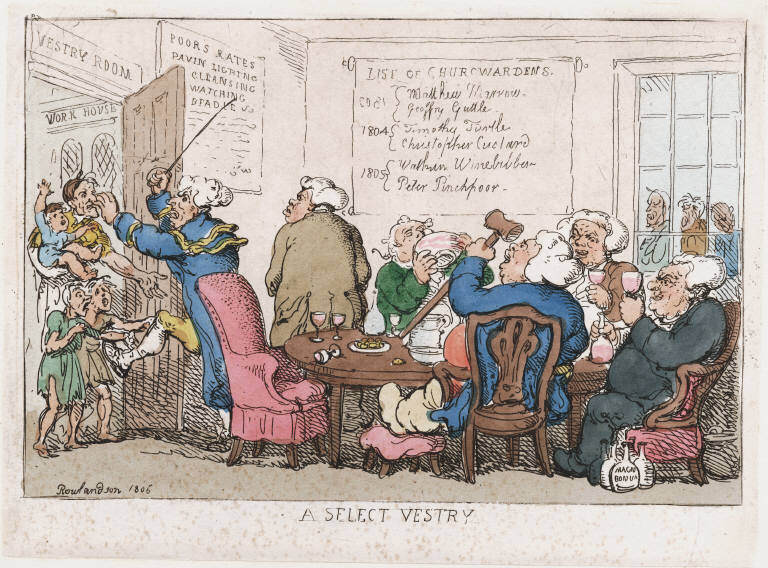

Thomas Rowlandson, A Select Vestry, 1806. Lewis Walpole Library, 806.0.49. © The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Thomas Rowlandson, A Select Vestry, 1806. Lewis Walpole Library, 806.0.49. © The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Introduction

The primary responsibility for poor relief in London rested with the individual parishes of the City of London and Middlesex, which, from the passage of the Elizabethan Poor Laws, were charged with electing overseers of the poor, who in turn could both raise a local tax or rate (based on the notional annual rent that might be charged for an individual property), and distribute the resulting income to needy parishioners.1 Which parishioners were entitled to apply for relief under this system was then defined by the Laws of Settlement. The initial Act defining the meaning of a settlement was passed in 1662, but was substantially revised in the 1690s.2 The workings of these Acts, and their implementation by the parishes, was in turn monitored by the local Justices of the Peace. Any JP could hear appeals by paupers against a parish, and order relief as he saw fit, or refer the matter to Quarter Sessions. Justices were further charged with confirming both the annual overseers' accounts and the secure election of new overseers once a year at the Easter meeting of the parish vestry.

The system that resulted has been described as a welfare state in miniature. But the patchwork and varied nature of local government in the metropolis, and in England and Wales more generally (the poor law in Scotland and Ireland were administered differently), ensured that a wide range of different levels and types of relief could be found even in neighbouring parishes. Competing layers of local government in the form of the parishes (and in particular the powerful and populous parishes of Westminster), the City of London itself, the Middlesex Bench and Court of Burgesses also contributed to ensuring that no single system nor set of administrative records ever fully encompassed the experience of a single pauper, much less the poor population of the metropolis as a whole.

Poor Relief and Charity

The boundaries between parochial relief and charity were also markedly porous. Throughout the eighteenth century, some parishes retained a distinction between money collected voluntarily for the poor after church -- known as the Collection and distributed to the most established paupers; and money raised as a rate or tax on householders and distributed to the simply needy. Among the parishes whose records are reproduced on this site, those of St Botolph Aldgate clearly make this distinction as seen in its volume of Payments to Paupers (AP). Most parishes also administered a range of bequests and gifts to the poor, frequently restricted by gender, age or perceived respectability. As a result, the system was both highly localised, and highly complex. Nor should we make an artificial division between poor relief and charity. From the late 1730s, in response to the passage of the Mortmain Act, London witnessed a remarkable flowering of Associational Charities. The Foundling Hospital, The Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes, and The Marine Society are simply the best known from among dozens of such institutions.3 These charities were frequently used by parishes as a means of keeping their own levels of expenditure low. Parish orphans and foundlings, for instance, were regularly given over to the Foundling Hospital.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 1740-45, B1066, LL ref: WCCDMV362070058.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 1740-45, B1066, LL ref: WCCDMV362070058.

Begging and Vagrancy

There is also a further variety of charity that has left almost no records, but which nevertheless was probably the single most extensive form of poor relief available to needy Londoners: casual charity given to the poor on the streets, and at one's own door. Generalised complaints about the activities of beggars can be found in both the records of local government and the criminal justice system, but beggars remained a prominent fixture of the London street scene, suggesting in turn, that begging could form an important source of income. The parish poor were also themselves encouraged to supplement their relief with income generated through begging. And although superficially directed at limiting street begging, the passage in 1697 of the Badging Act, requiring all paupers in receipt of parish relief to display the initials of their parish and the letter P, to signify their status, had the effect of creating a cadre of the deserving poor whom parishioners could relieve with casual alms in the certain knowledge that the recipient had been vetted by the parish.

The complexity of the system was further increased by the workings of the laws against vagrancy. Having evolved in parallel to the Old Poor Law, vagrancy legislation created a distinction between criminal vagrants and deserving paupers.4 This distinction, however, grew less clear in the second half of the seventeenth century, following the passage of the Laws of Settlement, as both systems effectively worked to return individuals to their place of settlement. The inclusion of both vagrancy examinations and settlement examinations in the same parochial archives of Pauper Examinations (EP) (occasionally involving the examination of the same people) reflects this confusion. But, unlike parish paupers, vagrants came under the criminal justice system, and were the direct responsibility of the City of London and County of Middlesex. This is particularly important as the charge of transporting vagrants, as opposed to paupers, to their home parishes fell to the county and City rates, rather than to the parishes. Once passed to their home parish, and punished (normally with a week's detention at hard labour in a House of Correction), however, vagrants became the responsibility of the parish relief system. The tension between these two parallel and intertwined systems forms one of the major driving forces in the changing experience of eighteenth-century paupers, and the crisis in the management of vagrants in the 1780s forms a crucial turning point in the history of social welfare in the capital.

Oversight

The labyrinthine and chaotic character of the system was in part mitigated by the roles of the Middlesex Bench and Grand Jury, and of the Lord Mayor and Common Council in the City of London.5 The Grand Jury and Lord Mayor regularly issued policy documents seeking to address specific issues associated with poverty and disorder, for instance, seeking to suppress illegal markets for used clothing, or particular types or sites of begging "with menaces", or in Lincoln's Inn Fields. The Middlesex Bench and London Common Council also attempted to create overarching policies within which the parishes could work. In the City, for instance, the Common Council regularly ordered the redistribution of income from rich areas to poorer parishes. And both the Middlesex Bench and the Common Council acted as courts of appeal for disputed cases of pauper settlement and relief (which could in turn be further appealed to the Court of King's Bench). Some attempts were made to implement City- and county-wide reforms, such as the revival of the City's London Workhouse in 1698, but these reforms had a limited impact on the general system of relief.6

Workhouses

More significant for the experience of poor Londoners than attempts to create metropolitan-wide change was the activities of subsets of individual parishes. From the mid 1720s, following the passage of the Workhouse Test Act in 1723, and influenced by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, most of the large and increasingly urban parishes of Westminster established extensive workhouses, each accommodating hundreds of paupers, and requiring bureaucratic and professional management on a new scale.7 In the following decade the much smaller parishes of the City of London began to contract out their own poor relief services to independent undertakers, resulting, particularly from the late 1730s, in the development of a series of contract workhouses and madhouses located at the periphery of the City in areas such as Hoxton and Hackney.8

Paul Sandby, Old Clothes to Sell, 1759. © Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery.

Paul Sandby, Old Clothes to Sell, 1759. © Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery.

In 1776 a Parliamentary enquiry established that there were twenty-five workhouses in the City of London and Westminster, housing over 6,000 individual paupers (the workhouse belonging to St Martin in the Fields alone held over 700 individuals). And in the broader county of Middlesex, there were a further sixty-one houses, and over 8,800 inmates.

From the perspective of the poor themselves, the most enduring and characteristic aspect of poor relief in the capital was its sheer complexity. Between the parishes, with their varieties of relief - doles and workhouses -and the Associational Charities; and between casual relief, hospitals and infirmaries, work and educational schemes, clothing charities, and a dense calendar of events, each with its doles and alms, the poor were faced with perhaps the most densely patterned set of resources available to any group in Europe or beyond.

A Brief Chronology of Change

Although the basic parochial structures that underpinned poor relief remained largely unchanged through the course of the eighteenth century, gradual and incremental developments at the level of the parish, the City, the metropolis and nationally all impacted on the ways in which the system worked, cumulatively amounting to a significant transformation. These changes can be briefly characterised as follows:

- 1670-1690: The overall level of national expenditure on the poor grew significantly, turning a programme of partial support into a comprehensive parochial welfare system.

- 1690-1710: Extensive, but failed attempts to reform the Poor Law on a national level both encouraged individual cities, including London, to establish Corporations of the Poor, and led to a series of small but significant changes in poor law practice, including badging, and the creation of a certificate system that substantially ameliorated the workings of the Settlement Laws.

- 1700-1720: First charity schools and then working charity schools, or industrial schools, popularised by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, were created in most London parishes, seeking to address the problem of child poverty and under-employment through education and work discipline.

- 1723-1750: These decades saw the development of a parochial workhouse system following the passage of the Workhouse Test Act of 1723. By mid-century most urban parishes, most especially in the metropolis, either ran their own workhouses, or contracted with independent undertakers or other parishes to care for the dependent poor. Although the aspiration was to impose a workhouse test, and force the able bodied to work, these rapidly evolved into general institutions largely occupied with care of the sick, the orphaned and the elderly.

- 1740-1760: Following the passage of the Mortmain Act of 1736, which made it illegal to establish charitable trusts through a will at death, a series of Associational Charities, dependent on regular subscriptions, were founded, catering for what might be described as popular or emotionally engaging forms of poverty.

- 1750-1760: The mid-century witnessed both renewed attempts at national reform of the poor law, and the growing desire to incorporate issues around poverty within an analysis of crime and social order.

- 1760-1770: Jonas Hanway's two Acts, passed in 1762 and 1767, substantially impacted on the treatment of poor children and apprentices by London's parishes. This decade also witnessed a series of poor law scandals, the Elizabeth Brownrigg case being the most widely reported.

- 1780-1800: The system of transporting London workhouse children to the spinning mills of Lancashire and Yorkshire was instituted; and the system of policing vagrancy fell into crisis, particularly following the Gordon Riots. Overall, expenditure on both the poor and vagrants grew significantly through these decades, reaching a crisis point during the 1790s.

Back to Top | Introductory Reading

Historical Perspectives

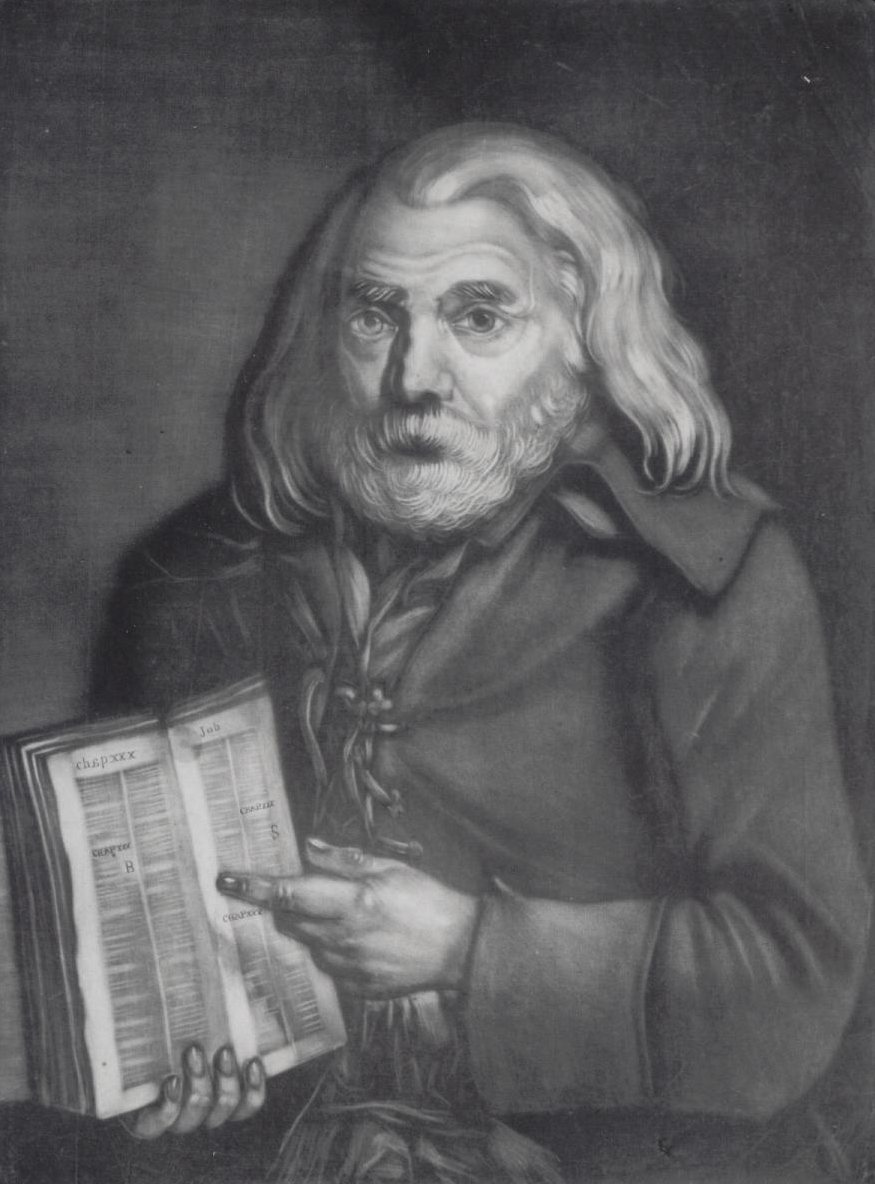

Simon Eedy, c.1780. NPG D1828. © National Portrait Gallery.

Simon Eedy, c.1780. NPG D1828. © National Portrait Gallery.

The history of poor relief in eighteenth-century London has not generated a coherent historical analysis. The largest body of directly relevant scholarship has been primarily concerned to use the system of relief to explore the evolution of the state - both local and national. Starting with the work of E.M. Leonard on the sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries, and furthered by Sidney and Beatrice Webb and Dorothy Marshall, the broad outlines of the development of the national system was characterised in the first half of the twentieth century as a story of gradual improvement and growing efficiency.9 In this literature the eighteenth century tends to be depicted as a period noteworthy primarily for the inefficiency and corruption of parochial administration. In most respects this early literature depicts eighteenth-century practice as a low point, from which the system gradually improved.

More recently, this tradition of administrative analysis in pursuit of a history of governance has been furthered in the work of Paul Slack, Steve Hindle and Joanna Innes. Paul Slack, in particular, has charted the evolution of urban relief experiments from the fifteenth century to the eighteenth, and suggested that the development of Associational Charities in the mid-eighteenth century as supplements to parochial relief created a positive context that allowed social problems to be more effectively addressed and for the total amount of resources dedicated to the poor to increase. He sees the fifteenth and eighteenth centuries as two ends of a period dominated by state-led innovation.10 Steve Hindle has produced a similar narrative for the evolution of relief, concentrating on rural areas, and emphasising the limited and discretionary nature of parochial provision.11 In contrast, working specifically on the eighteenth century, Joanna Innes has illustrated both the uniquely comprehensive nature of the English system by comparison to its European counterparts, and the underlying strength of what she has described as the "mixed economy of welfare" in England.12

Economic historians have taken a slightly different approach to many of the same topics. In particular, Steven King has charted a complex landscape of eighteenth-century relief, characterised by stark regional differences in the levels of relief, with Northern England suffering marginal levels of support, while a system catering for "welfare junkies" evolved in the South.13

There is a substantial body of further work that addresses specific aspects of the history of London's poor relief from a variety of disciplinary perspectives. The history of medicine has been particularly important in this regard, with the work of Kevin Siena, Elaine Murphy and Alysa Levene all forming important contributions that have done a great deal to chart the history of medical care as experienced by the poor.14 Economic history has similarly addressed the issue of levels and distribution of poverty and to a lesser extent poor relief, with studies by Craig Spence, Leonard Schwarz and Jeremy Boulton; which in their turn have built on the much older, but still overwhelmingly important work of Dorothy George.15 David Green's recent study of nineteenth-century London poor relief, written from the perspective of historical geography, provides the most detailed account of poor relief in London for the period after 1790.16

Vagrancy has been much less studied, with the work of Nicholas Rogers and Audrey Eccles forming significant exceptions to an otherwise largely unexplored topic; while the detailed history of associational charities has been the subject of important volumes by Donna Andrew, Ruth McClure, and taking the form of a biography, by James Stephen Taylor.17

Recent work by Tim Hitchcock has attempted to reconfigure this literature and reconstruct the history of poverty and its relief from the perspective of the poor themselves, and their experience of using a variety of governmental systems, as part of a personal pauper strategy.18

Areas of substantial intellectual debate and disagreement include:

- Whether the poor had a right to relief, and whether this was legally enforceable or customary.

- How effective were the strategies of the poor in accessing relief, and whether these strategies amounted to an effective form of agency.

Areas that have not been substantially addressed include:

- The relationship between charities and parochial relief.

- Why and how expenditure on poor relief grew so substantially through the course of the century, particularly in London (and prior to the subsistence crises associated with the 1790s).

Back to Top | Introductory Reading

Introductory Reading

- Andrew, Donna T. Philanthropy and Police: London Charity in the Eighteenth Century. Princeton, 1989.

- Ben-Amos, Ilana Krausman. The Culture of Giving: Informal Support and Gift-Exchange in Early Modern England. Cambridge, 2008.

- Green, David. Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1860. Farnham, Surrey, 2010.

- Hindle, Steve. On the Parish?: The Micro-Politics of Poor Relief in Rural England, c.1550-1750. Oxford, 2004.

- Hitchcock, Tim. Down and Out in Eighteenth-Century London. 2004.

- Innes, Joanna. Managing the Metropolis: London's Social Problems and their Control, c.1660-1830. In Clark, Peter and Gillespie, Raymond, eds, Two Capitals: London and Dublin 1500-1840 (Proceedings of the British Academy, 107). Oxford, 2001, pp. 53-79.

- King, Steven. Poverty and Welfare in England, 1700-1850. Manchester, 2000.

- Lees, Lynn Hollen. The Solidarities of Strangers: The English Poor Laws and the People, 1700-1948. Cambridge, 1998.

- Slack, Paul. From Reformation to Improvement: Public Welfare in Early Modern England. Oxford, 1999.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 The significant legislation was passed between 1598 and 1601, and was codified in 43 Elizabeth c. 2. ⇑

2 See 14 Charles II c. 12; 3 William & Mary c. 11 and 8 & 9 William III c. 30. ⇑

3 Donna T. Andrew, Philanthropy and Police: London Charity in the Eighteenth Century (Princeton, 1989). ⇑

4 Nicholas Rogers, Policing the Poor in Eighteenth-Century London: The Vagrancy Laws and Their Administration, Histoire Sociale / Social History, 24 (1991), pp. 127-47. ⇑

5 Joanna Innes, Managing the Metropolis: London's Social Problems and their Control, c.1660-1830, in Peter Clark and Raymond Gillespie, eds, Two Capitals: London and Dublin 1500-1840 (Proceedings of the British Academy, 107, Oxford, 2001), pp.53-79. ⇑

6 Stephen M. MacFarlane, Social Policy and the Poor in the Later Seventeenth Century, in A. L. Beier and Roger Finlay, eds, London, 1500-1700: The Making of the Metropolis (1986), pp. 252-77. ⇑

7 Tim Hitchcock, Paupers and Preachers: The SPCK and the Parochial Workhouse Movement, in Lee Davison, et al., eds, Stilling the Grumbling Hive: The Response to Social and Economic Problems in England, 1689-1750 (Stroud, 1992), pp. 145-66. ⇑

8 Elaine Murphy, The Metropolitan Pauper Farms 1722-1834, London Journal, 27:1 (2002), pp. 1-18. ⇑

9 Most significantly, Beatrice and Sidney Webb, English Local Government: English Poor Law History: Part 1. The Old Poor Law (1927). ⇑

10 Paul Slack, From Reformation to Improvement: Public Welfare in Early Modern England (Oxford, 1999). ⇑

11 Steve Hindle, On the Parish?: The Micro-Politics of Poor Relief in Rural England, c.1550-1750 (Oxford, 2004). ⇑

12 Joanna Innes, The 'Mixed Economy of Welfare' in Early Modern England: Assessments of the Options from Hale to Malthus (c.1683-1803), in Martin J. Daunton, ed, Charity, Self-interest and Welfare in the English Past (1996), pp. 139-80. ⇑

13 Steven King, Poverty and Welfare in England, 1700-1850 (Manchester, 2000). For the reference to "welfare junkies", see p. 268. ⇑

14 Kevin Siena, Venereal Disease, Hospitals and the Urban Poor: London's "Foul Wards," 1600-1800 (Rochester, New York, 2004); Murphy, Metropolitan Pauper Farms ; and Alysa Levene, Children, Childhood and the Workhouse: St Marylebone, 1769-1781, London Journal, 33:1 (2008), pp. 41-59. ⇑

15 See for example, Craig Spence, London in the 1690s: A Social Atlas (2000); Leonard D. Schwarz, London in the Age of Industrialisation: Entrepreneurs, Labour Force and Living Conditions, 1700-1850 (Cambridge, 1992); and Jeremy Boulton, The Poor Among the Rich: Paupers and the Parish, in the West End, 1600-1724, in Paul Griffiths and Mark S. R. Jenner, eds, Londinopolis: Essays in the Cultural and Social History of Early Modern London (Manchester, 2000), pp. 197-225. ⇑

16 David Green, Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1860 (Aldershot, 2010). ⇑

17 For vagrancy see Rogers, Policing the Poor in Eighteenth-Century London. For associational charities see Andrew, Philanthropy and Police and James Stephen Taylor, Jonas Hanway, Founder of the Marine Society: Charity and Policy in Eighteenth-Century Britain (1985). ⇑

18 Tim Hitchcock, Down and Out in Eighteenth-Century London (2004). ⇑