Hospitals

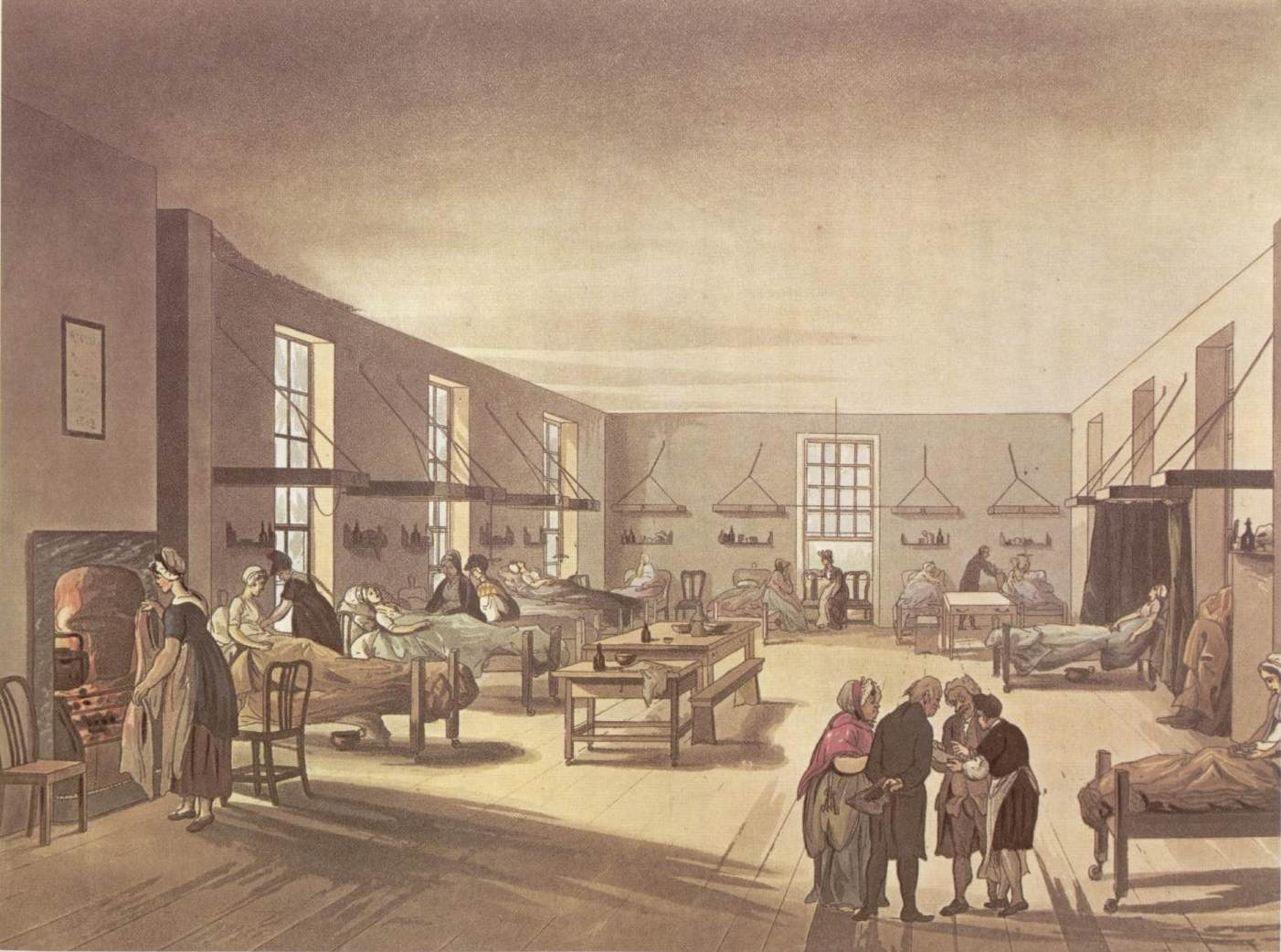

Thomas Rowlandson, Middlesex Hospital, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Thomas Rowlandson, Middlesex Hospital, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Introduction

Eighteenth-century London was for many an unhealthy place to live, but there was growing institutional provision for curing the sick and the lame. In addition to the extensive care available through the parish (available from parish nurses and workhouses), and a variety of more or less qualified doctors, apothecaries and "quacks" (for those who could afford them), by 1800 Londoners had available almost twenty general or specialist hospitals where treatment could be sought. These hospitals were a valuable source of medical care for the poor, particularly for those who did not have a settlement in London and therefore had no access to parochial relief.

While the two oldest hospitals date back to the middle ages, most were founded in the eighteenth century as a result of the growth of associational charities. Although admission was restricted and the medical care available was limited and possibly sometimes counter-productive, these hospitals nonetheless contributed to the improvement in Londoners' living standards which occurred in the second half of the century. By 1800, when London hospitals catered for between twenty and thirty thousand patients a year, recorded baptisms in the metropolis were for the first time beginning to exceed burials.1 Reflecting the wider understanding of the charitable functions of hospitals prevalent in the pre-modern period, these hospitals attempted to cure more than physical illnesses, paying attention to the patients' moral and spiritual care as well.

The records of one hospital, St Thomas's, are included in London Lives.

Royal Hospitals

London's oldest hospitals, both general hospitals founded by Augustinian monks in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, were St Bartholomew's in West Smithfield, and St Thomas's in Southwark. Both were dissolved during the dissolution of the monasteries in the 1530s and refounded shortly thereafter by royal charter under the government of the City of London, which also had responsibility for Bethlem Hospital, for the insane, and Bridewell Hospital and Prison, which housed homeless children and punished the disorderly poor. All were endowed with lands to provide them with a steady, though insufficient, income. Owing to their endowments and royal charters, these hospitals felt a responsibility for caring for a wider range of illnesses than the voluntary hospitals. Despite concerns about both physical and moral contagion, both St Thomas's and St Bartholomew's cared for fever patients and those with venereal disease, though they kept the latter separate from the other patients, and charged higher fees.

St Thomas's Hospital, Admissions Register, 1796, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms. HO1/ST/B/003/011, LL ref: LMTHRH554110005.

St Thomas's Hospital, Admissions Register, 1796, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms. HO1/ST/B/003/011, LL ref: LMTHRH554110005.

Voluntary Hospitals

With the growth of associational charities in the eighteenth century, several hospitals were founded by philanthropic men who wished to ameliorate the lives of the poor, contribute to the increasing population and prosperity of the nation, and improve their own social position. These hospitals tended to be more selective than the royal hospitals in the range of people and conditions they cared for, and included:

- The Westminster Hospital, founded in 1720 "for relieving the sick and needy and other distressed persons".

- Guy's Hospital, founded by Thomas Guy, a printer and publisher who made his fortune in stocks, in 1727. Unusually, Guy's was intended for incurables, including lunatics.

- St George's Hospital, founded in 1734 in Knightsbridge (where patients could receive the benefit of country air), for the relief of poor, sick and disabled persons.

- The Foundling Hospital, established in 1739 by Thomas Coram, a sea captain, for the care of infants abandoned by their parents.

- The London Hospital, founded in 1740 in Moorfields, for the sick and injured poor of the East End, particularly manufacturers and seamen and their families.

- The Lock Hospital, opened by William Bromfield in 1747 for the treatment of venereal disease.

- The Middlesex Infirmary, founded in 1754 on Windmill Street, for the sick and lame, and cancer patients.

- The Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes, founded in 1758.

In addition, several lying-in hospitals were established to assist women in giving birth, starting with the Lying-in Hospital for Married Mothers (later the British Lying-in Hospital), founded in 1749. Most, but not all, restricted entry to married women.

Criteria for Admissions

The criteria for admission to these hospitals varied, but it was never automatic. Hospitals rarely admitted those with contagious diseases, and many prevented entry to those with venereal disease, or charged higher fees. Only the two royal hospitals and Guy's accepted fever patients, and only Guy's and the Middlesex admitted "incurable" patients. Admission typically required some combination of nomination by a governor or subscriber, a petition, the payment of fees, and provision of a surety who guaranteed to pay the burial expenses if the patient died. In many cases, fees were paid by friends and family, or by the parish, though in some cases of extreme need hospitals waived the fees. It was typically expected that patients with a settlement in London should be paid for by their parish. Sureties were provided by the parish, employers, a military or naval officer in the case of wounded soldiers or sailors, or commercial bondsmen. Most hospital patients were from the lower classes as wealthier Londoners preferred to pay doctors to attend to them in their homes.

Care and Conditions

Eighteenth-century medical care was limited by incorrect diagnoses and the limitations of the prevailing humoural understanding of the body, but this was true both inside and outside hospitals. Surgery was rarely carried out due to the lack of anaesthesia and was primarily confined to amputations and lithotomies (removal of stones from the urinary bladder). Instead, what hospitals offered patients besides food and a bed were basic medicines and external cures.

Conditions inside hospitals, however, were often unhygienic. Patients typically shared beds, and bed bugs were common. Contagious diseases such as typhus could spread easily. After visiting London's hospitals, the reformer John Howard complained in 1789 that "white-washing of the wards is seldom or never practised, and injurious prejudices against washing floors, and admitting fresh air, are suffered to operate".2 Nonetheless, death rates were usually low (under 10 per cent) and most patients were cured and discharged. Perhaps this is not surprising given that those deemed incurable or suffering from contagious diseases were usually not admitted, and few surgical operations were carried out. Most eighteenth-century Londoners expected to die at home.

William Hogarth. A Harlot's Progress, Plate V, She Expires, while the Doctors are Quarrelling, April 1732. © London Lives.

William Hogarth. A Harlot's Progress, Plate V, She Expires, while the Doctors are Quarrelling, April 1732. © London Lives.

Reflecting the broader functions of hospitals at the time, as well as the reforming zeal of some of the founders, patients were often subjected to attempts at moral and spiritual care as well as medical cure. Patients were expected to work and receive religious instruction. Those at the London Hospital were required to thank the Hospital Committee on their discharge and go to their parish church to thank God for their cure. Rules prevented patients from leaving hospitals without a pass, and punished those caught swearing and cursing, drinking, stealing, and behaving immodestly.

The very existence of these regulations, of course, suggests that some patients failed to follow them. Some ran away, or were discharged for bad behaviour. Patients also abused the system by lying about their personal circumstances and medical conditions in order to gain admission, for example hiding the fact they were pregnant, or were suffering from smallpox, fever or venereal disease, and they often discharged themselves when they felt they had received sufficient treatment. While rules and regulations constrained the medical care available, the poor learned how to navigate them in order to get the care they needed. The very fact so many institutions came to care for those with venereal disease, for example, despite its immoral connotations and the unpleasant and expensive treatments involved, indicates that the demands of the poor shaped the provision of medical care in hospitals.

Towards the end of the century, however, changing medical attitudes and the growing role hospitals played in medical education altered the relationship between doctors and patients. Rather than treating disease as a problem of both mind and body, and engaging with patients in discussions about their conditions and cures, doctors and surgeons began to focus on the body only, excluding the patient from their deliberations. Whether this shift was also a response to the increasing demands poor patients placed on doctors is impossible to determine, but the result was to marginalise the role of the patient in the provision of medical care.

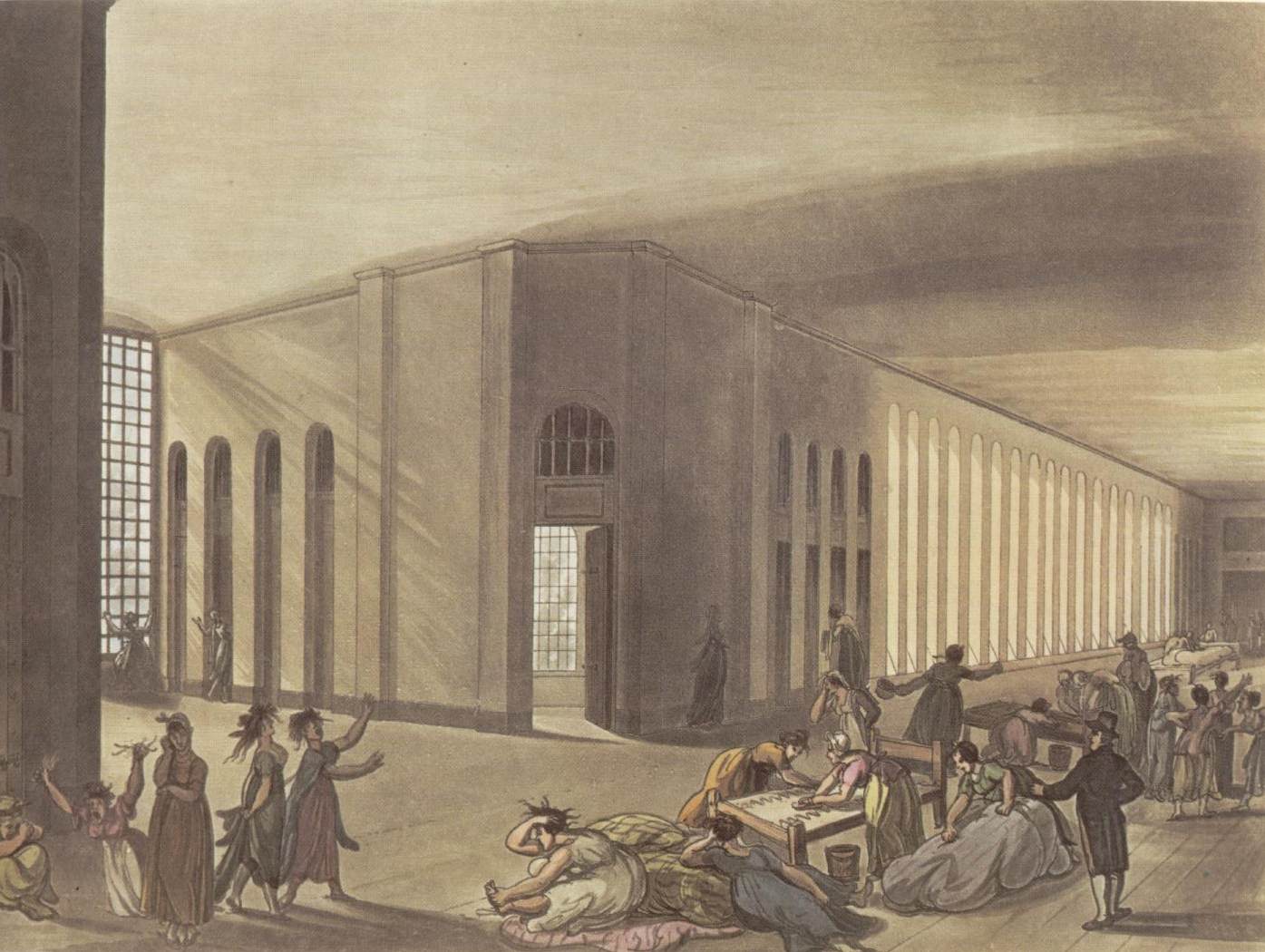

Thomas Rowlandson. St Luke's Hospital, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Thomas Rowlandson. St Luke's Hospital, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Conclusion

While the standard of medical care was low, hospitals provided an important service to the poor which had previously been unavailable, and the poor made the most of these opportunities. Together with the introduction of dispensaries, which treated contagious diseases and provided drugs for 50,000 poor patients a year in the London area at the end of the century, hospital care contributed to the improvement in living standards and decrease in mortality which occurred in late eighteenth-century London.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keyword Hospital:

Lives using the keywords St Bartholomew's Hospital:

Introductory Reading

- Andrew, Donna T. Philanthropy and Police: London Charity in the Eighteenth Century. Princeton, 1989.

- Porter, Roy. Cleaning up the Great Wen: Public Health in Eighteenth-Century London. Medical History, supplement number 11 (1991), pp. 61-75.

- Siena, Kevin. Venereal Disease, Hospitals and the Urban Poor: London's "Foul Wards," 1600-1800. Rochester (NY), 2004.

- Woodward, John. To Do the Sick No Harm: A Study of the British Voluntary Hospital System to 1875. 1974.

Footnotes

1 Roy Porter, Cleaning up the Great Wen: Public Health in Eighteenth-Century London, Medical History, supplement number 11 (1991), pp. 61-75. ⇑

2 John Howard, An Account of the Principal Lazarettos in Europe (Warrington, 1789), p. 141. ⇑