St Thomas's Hospital

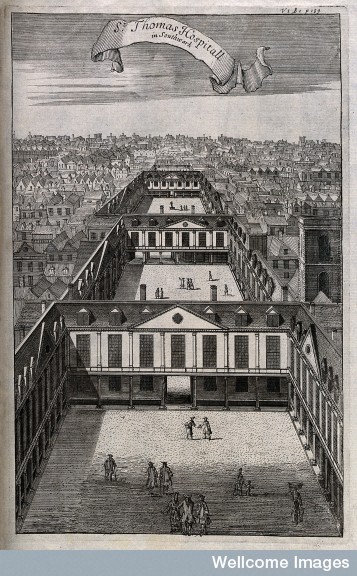

Thomas Cartwright. Old St. Thomas's Hospital, Southwark, 1739. Wellcome Library, ICV No 14033. © The Wellcome Library, London.

Thomas Cartwright. Old St. Thomas's Hospital, Southwark, 1739. Wellcome Library, ICV No 14033. © The Wellcome Library, London.

Introduction

St Thomas's Hospital had its origins in an Augustinian infirmary, established during the twelfth century and dissolved in 1540. The Hospital was refounded by royal charter in 1551, one of five major endowed royal hospitals established in London in the mid-sixteenth century, which also include Bridewell. St Thomas's functioned as a general hospital for the sick poor, including sufferers of venereal disease. The Hospital occupied the same site, on St. Thomas's Street in Southwark, for more than six centuries, from 1215 to 1862; it was, however, transformed by a major rebuilding programme at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Its extensive endowments gave St Thomas's a degree of financial security that was shared by few other hospitals, though its wealth and influence also made St Thomas's the subject of political interference from outside and factionalism within. Throughout the eighteenth century the Hospital continued to seek other sources of income, especially for large projects such as the rebuilding. It also charged patients admission fees, a policy which was condemned by the Hospital's critics for limiting the ability of the very poor to access its services.

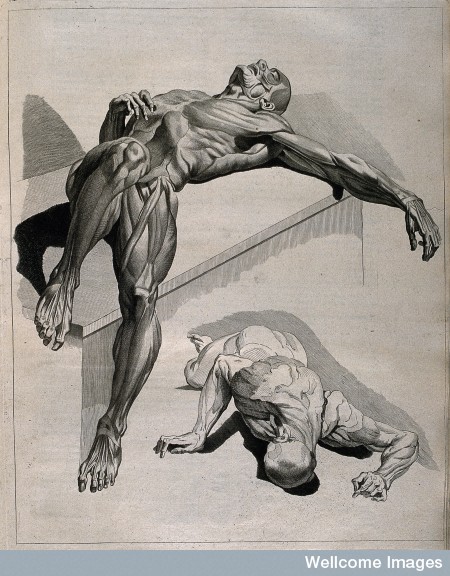

Jacques Gamelin. Nouveau Recueil d'Ostéologie et de Myologie. 1779. Wellcome Library, 569725i and ICV No 9027. © Wellcome Library, London.

Jacques Gamelin. Nouveau Recueil d'Ostéologie et de Myologie. 1779. Wellcome Library, 569725i and ICV No 9027. © Wellcome Library, London.

Government

The Hospital was governed by its General Court of Governors, headed by the Hospital's president, which usually met annually. Existing governors elected newcomers to join them for life. By its royal charter, St Thomas's governors were supposed to have the freedom of the City, but in the eighteenth century this restriction was largely ignored, and there could be be more than 200 governors at any one time. Anyone elected had to be wealthy enough to afford the customary £50 gift to the Hospital.

The active governors who oversaw day-to-day management of the Hospital formed a much smaller group. By the end of the seventeenth century, much routine administration was delegated to committees working with the Hospital's senior administrators, the secretary and treasurer. Governors also served with senior medical staff as takers-in overseeing patient admissions. In addition, visiting governors regularly toured the wards to inspect the Hospital and report any irregularities to the committees.

General Courts and the high profile governors who directed them were far less concerned with the minutiae of Hospital administration and patient care. The Minute Books (MG) of the General Court document the power they held through exploitation for political influence of the Hospital's extensive properties and revenues, as well as appointment to its senior medical and administrative posts. As a result, both the City and the crown frequently made efforts to gain control of the Hospital's Whig-dominated governing body.

Buildings

St Thomas's Hospital itself was untouched by the Great Fire of 1666, although many of its local properties were damaged or destroyed, causing short-term financial problems. However, the rebuilding of London that followed the fire undoubtedly exacerbated dissatisfaction with the cramped Hospital buildings. There had been few changes to the Hospital fabric since its refounding in the mid-sixteenth century and it was increasingly dilapidated and expensive to maintain.

A fund-raising campaign was launched, headed by the president of the Hospital, Sir Robert Clayton, and between 1693 and 1720 more than £37,000 was raised in order to create an elegant classical structure constructed around three spacious courtyards, along with improved accommodation for the Hospital's administrative staff. The rebuilt Hospital had nineteen wards, including two foule wards for venereal patients and a cutting ward, with room for more than 400 patients. Male and female patients were strictly segregated, as were the venereal patients.

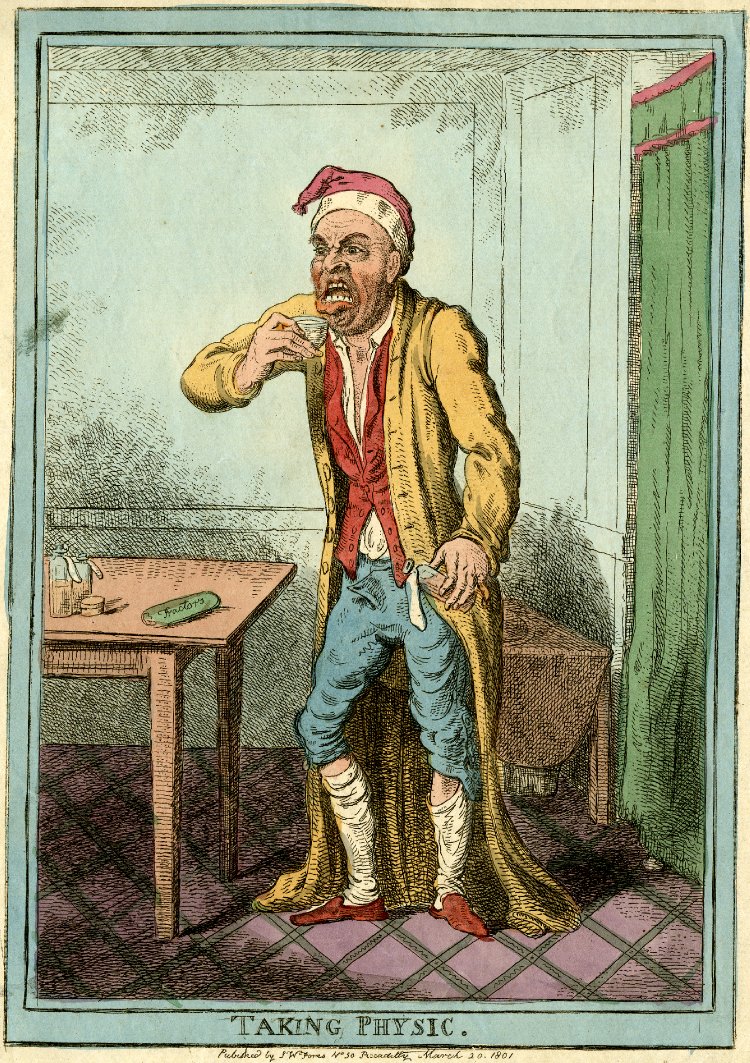

Isaac Cruikshank. Taking Physic. 1801 British Museum, Satires 9804. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Isaac Cruikshank. Taking Physic. 1801 British Museum, Satires 9804. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Medical Officers and Staff

The Hospital's senior medical officers, the physicians, surgeons and apothecaries, were elected for life by the General Court. There were three full physicians and three full surgeons, along with assistants and students. Physicians and surgeons were the only officers who did not reside in the Hospital. The apothecary was subordinate to the physicians and surgeons and was not permitted to marry or have a private practice.

The physicians and surgeons took turns to work with the governors each week admitting new patients. They also had regular hours for visiting their patients, attending on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays from 11 am to 1 pm. The apothecary and medical students largely took responsibility for day-to-day routine treatment of patients.

The nursing staff had its own hierarchy. The matron was an elected officer, lived in the Hospital, and was usually of higher social status than the sisters and nurses. She was a purely administrative officer, responsible for the domestic management of the infirmary, and supervision and discipline of servants and nurses.

The sisters were the most senior nursing staff on the wards. There was a sister on each ward, with two assistant nurses, who were on duty from 6 am until lights-out at night. The sisters and their assistant nurses lived in and had to be single or widowed. They were responsible for patient care (except for dressing wounds) and discipline, as well as housekeeping duties,and organizing food and drugs, fuel and lighting, and cleaning. At night, night-watches took over, making regular rounds of the wards and inspecting the most ill patients. Generally the watches were poor older women who lived in their own homes, receiving a modest wage to supplement their incomes. Nevertheless, even the most lowly of Hospital nurses were regarded in a more favourable light than were parish nurses.

St Thomas's Hospital, Admissions Register, 1796, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms. HO1/ST/B/003/011, LL ref: LMTHRH554110005.

St Thomas's Hospital, Admissions Register, 1796, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms. HO1/ST/B/003/011, LL ref: LMTHRH554110005.

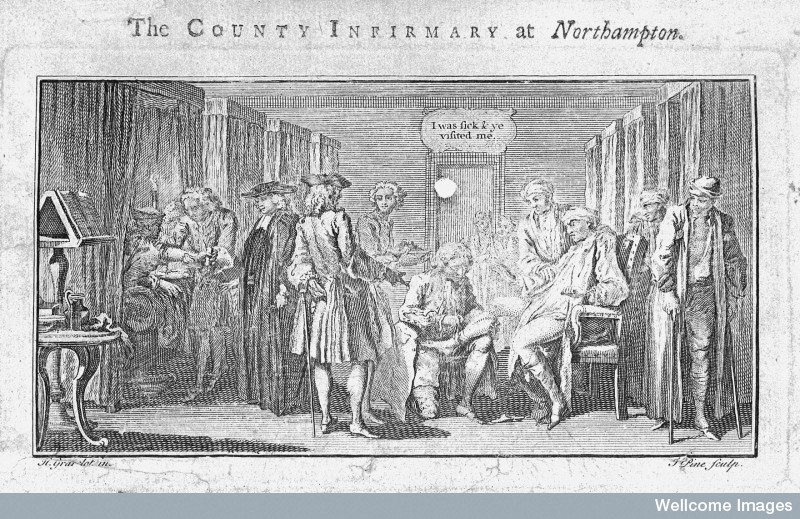

Admissions and Patients

St Thomas's catered for patients with a wide range of medical and surgical conditions. The Hospital excluded those classed as "incurable" and the insane, but it did admit patients with venereal diseases, for which there were specialist wards. Hospital rules dictated strict segregation of the sexes and of clean from foul patients. Each ward was named, and when there were four foul wards, Job and Naples were for men, and Magdalen and Susannah for women. Patients were normally not permitted to stay longer than three months, after which they were deemed incurable.

The Hospital treated large numbers of patients. Several thousand were admitted for treatment on the Hospital wards every year, with more treated as outpatients: in 1800 the total number of in-patients was more than 3,200, with a further c.4,700 outpatients. In wartime the numbers were often supplemented by large numbers of wounded soldiers and sailors. Vagrants, paid for by the City of London, also made up a significant portion of the Hospital's inmates; particularly as the number of vagrants passing through London increased in the 1780s.

For much of the eighteenth century, most patients were required to pay fees for their treatment, and to provide financial securities to cover burial costs if they died in hospital. Venereal patients were charged considerably higher fees than "clean" patients (10s 6d versus 3s 6d in the late eighteenth century), but nonetheless comprised a substantial proportion of the Hospital's population, approximately 28 per cent in the 1770s.

The levying of these charges was criticised as exclusionary by supporters of voluntary hospitals. The governors could at their discretion waive fees for the poorest patients, but in practice most patients who could not pay their own way had to obtain financial support from their parish, other institutions or private patrons in order to obtain treatment. During the 1770s, about 9 per cent of patients were supported by their parishes, with women more likely to be sponsored than men. While the relationship between patients and private sureties is usually obscure, it seems that some chose to avoid or could not access poor relief institutions or family networks, and instead turned to commercial men (and occasionally women), often victuallers and alehouse keepers, who acted as sureties for a fee.

At some point, however, all had to enter into negotiations in order to obtain the Hospital's medical care. Gaining admittance to the Hospital was subject not only to the assessments of doctors but also the approval of lay Hospital governors acting as takers-in whose concerns were financial as much as medical.

County Infirmary, Northampton, from Richard Grey. A Sermon for ... Sick and Lame Poor. 1744. Wellcome Library, Slide number 4443. © Wellcome Library, London.

County Infirmary, Northampton, from Richard Grey. A Sermon for ... Sick and Lame Poor. 1744. Wellcome Library, Slide number 4443. © Wellcome Library, London.

Care and Conditions

The medical care provided was subject to the limitations of all available treatments in the eighteenth century. Nonetheless, and despite complaints about poor sanitary conditions, most patients left the Hospital in a better state than when they entered.

When John Howard visited the Hospital in September 1788 he found the "wards were fresh and clean, except the three foul wards... these were very offensive and had not a window open. There were no water closets." Although he found that "the bread was excellent", he complained about "the great quantities of beer brought from public houses into this and other hospitals" and the fact that since the patients could easily get in and out through the hospital gates, "the adjoining gin shops often prevent the efficacy of medicine and diet".1 These comments are more a reflection of new standards being applied than a statement of specific inadequacies of St Thomas's.

Despite Howard's complaints, death rates at St Thomas's were relatively low. In the year ending Easter 1726, it was reported that 4,873 patients were cured and 392 died, a mortality rate of 7.4 per cent. Similarly, in the year ending Easter 1735, 4,688 patients were cured and 307 died, a mortality rate of 6.1 per cent. Later in the century mortality rates were very similar: 7.1 per cent between 1773 and 1783, and 6.4 per cent between 1783 and 1793.2 These mortality rates were typical for hospitals in the eighteenth century, a time when most people expected to die at home.

The Hospital's authority over its patients extended beyond purely medical matters. The Hospital's governors were as much concerned with the souls as the bodies of the sick. Hospital rules required patients to attend services in the chapel every Sunday, as well as prayers on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday mornings (with the exception of the venereal patients, who were banned from entering the chapel). The rules (prominently displayed on the wards) also forbade swearing, assaulting other patients, stealing, gambling. excessive drinking and "immodest" behaviour. Strict segregation of men and women was practised. The movements of patients on the venereal wards were strictly circumscribed.

How conscientiously the rules were applied in practice, however, might depend on the willingness of volunteer governors to enforce them. The Hospital's records document various forms of disobedience including disruptive behaviour, harassing other patients or nurses, petty theft, and leaving the wards at night without permission. Some patients simply ran away before the completion of their treatment, especially venereal patients subjected to the deeply unpleasant and painful mercury-based "salivation" treatments.

Documents Included on this Website

- Lists of Governor Takers-In of Patients to St Thomas's (LT)

- Minute Books of Hospital/Guild Courts and Committees (MC)

- Minute Books of the Court of Governors of Bridewell/St Thomas's (MG)

- Out-Letter Books: Copies of Correspondence Sent from St Thomas's Hospital (LB)

- St Thomas's Admission and Discharge Registers (RH)

Introductory Reading

- McInnes, E. M. St Thomas' Hospital. 1963.

- Siena, Kevin Patrick. Venereal Disease, Hospitals and the Urban Poor: London's "Foul Wards" 1600-1800. Rochester (NY), 2004.

- Woodward, John. To Do the Sick No Harm: A Study of the British Voluntary Hospital System to 1875. 1974.

Online Resources

- History of St Thomas's Hospital

- St Thomas's Hospital Historical Collection

- Records of Patients in London Hospitals (LMA leaflet, pdf)

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 John Howard, An Account of the Principal Lazarettos in Europe (Warrington, 1789), pp. 134-35. ⇑

2 John Woodward, To Do the Sick No Harm: A Study of the British Voluntary Hospital System to 1875 (1974), pp. 126-28. ⇑