Justices of the Peace and the Pre-Trial Process

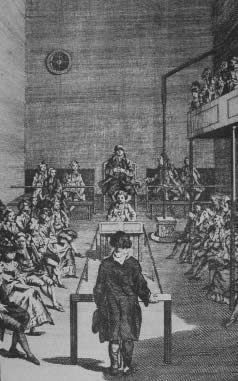

Thomas Rowlandson after Henry Wigstead. A Rotation Office. 1774. British Museum, Satires 5273. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Thomas Rowlandson after Henry Wigstead. A Rotation Office. 1774. British Museum, Satires 5273. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Introduction

In most respects the gatekeepers of the eighteenth-century criminal justice system were the Justices of the Peace. While any individual might initiate a prosecution, most prosecutors needed to appear before a Justice if a prosecution was to proceed. Once a criminal complaint was brought before him, a Justice of the Peace had a number of options, depending on the nature of the complaint, the wishes of the complainant, and his own preferences. Since Justices had so much discretion in how they enforced the law, it is important to know something about who they were, as well as the legal options available to them. Summary jurisdiction gave Justices extensive powers to punish petty offenders, though these were increasingly subject to judicial oversight. Traditionally, however, Justices had little flexibility when it came to suspected felons, who were supposed to be immediately committed to prison to await trial. Over the course of the eighteenth century the growing use of pre-trial hearings created an extra step in the judicial process, giving greater power to the Justices who conducted them. And at the end of the century the creation of stipendiary magistrates led to greater Home Office control over the work of JPs. In explaining how the Justices' pre-trial powers were reined in at the end of the eighteenth century, it is important to recognise the role not only of judicial and parliamentary reformers, but also of plebeian litigants, in terms of both the pressures created by the litigation they initiated and their challenges to the decisions Justices made.

Justices of the Peace

Created in the fourteenth century, Justices of the Peace were initially given the power to hear and determine felonies and petty offences against the peace. These powers were gradually added to over the centuries through a series of statutes giving them responsibility for numerous administrative matters, including poor relief. Justices were named in commissions of the peace granted by the crown for each county, and these could be renewed (and thus new justices appointed, and others dropped) at any time. During the "rage of party" in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries politically motivated purges and appointments periodically and occasionally dramatically altered the composition of the commissions of the peace, and had a significant impact on the criminal business heard at the Middlesex sessions. But from the 1720s these political alterations largely ceased and the number of Justices on the commission increased substantially during the rest of the century. While there were 129 Middlesex Justices in 1680 and 212 in 1702, this figure reached 499 in 1761.1

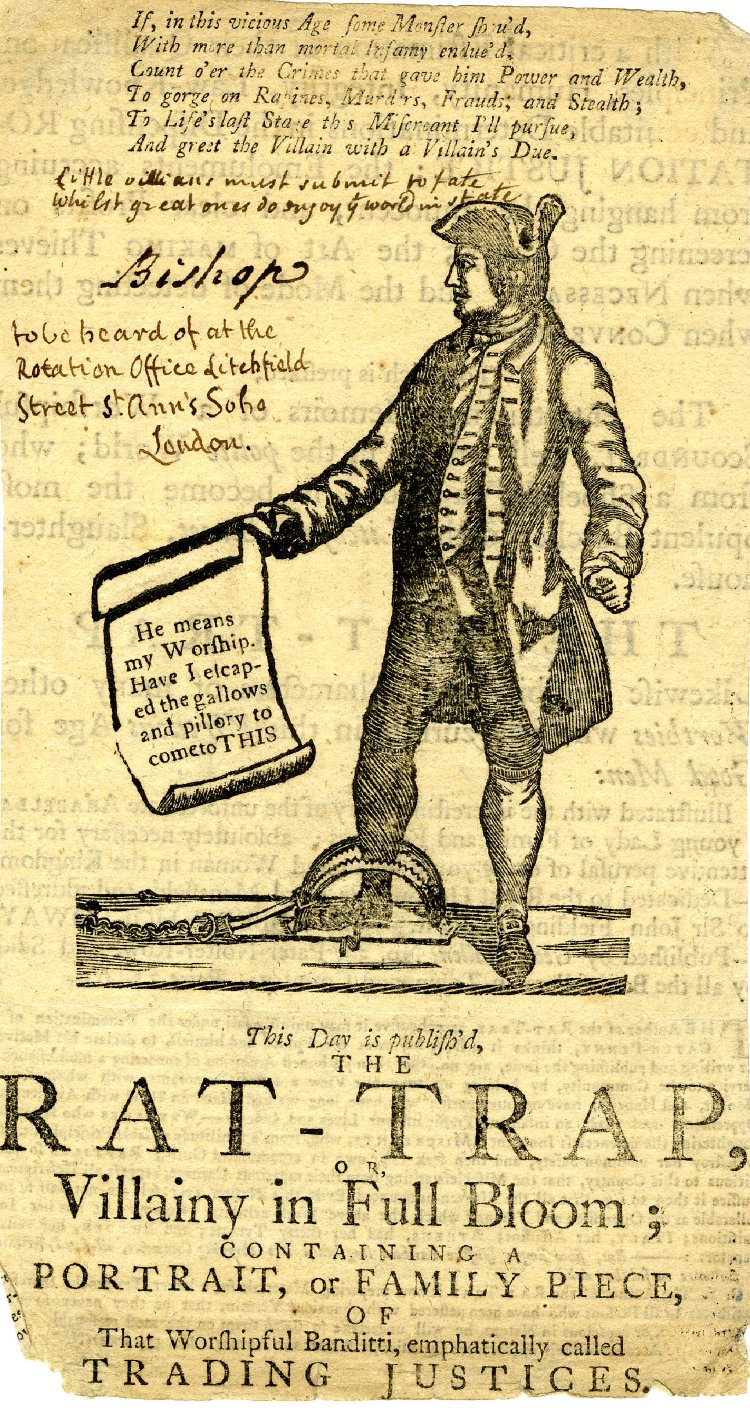

The rat-trap, or villainy in full bloom. 1773. British Museum, Satires 5197. © Trustees of the British Musuem. text

The rat-trap, or villainy in full bloom. 1773. British Museum, Satires 5197. © Trustees of the British Musuem. text

Justices were not paid by the government, though they were entitled to charge small fees for their services. They were expected to be leading men of property in their counties, but over the course of the eighteenth century it became increasingly difficult to find landed gentlemen who were willing to act in London, given the volume of business they had to deal with and the fact they were frequently subject to physical, verbal and legal abuse from their social inferiors. By the late eighteenth century the Middlesex commission was increasingly dominated by merchants and tradesmen. Despite the increase in the size of the commission, the number of active Justices, always a small proportion of the number appointed, decreased still further, as judicial business was increasingly dominated by a handful of zealous magistrates, who attracted a bad reputation as a result of their alleged low social status and corrupt practices.

Trading Justices

The low status of the Justices who conducted the majority of judicial business in the capital resulted in them being labelled "Trading Justices", because they allegedly treated the office primarily as a source of income. They were also accused of engaging in corrupt activities, such as committing alleged prostitutes to prison in order to share the fees with the gaolers, and fomenting disputes among the poor in order to profit from the fees of complainants. Recent scholarship, however, has demonstrated that the most active Justices in the metropolis were neither invariably corrupt nor of particularly low status, and that their judicial activities were simply a response to demands for their services, particularly from the poor. It is true that Trading Justices were concentrated in the poorer parts of the metropolis, such as in the East End parish of St Botolph Aldgate, and that they did issue large numbers of recognizances to attend sessions, but this does not mean their services were not valued by complainants who perhaps could not afford more substantial forms of legal action. In fact, it is possible that some of these Justices were paid salaries by local businessmen to carry out their work adjudicating complaints in the locality. Nonetheless, contemporary complaints concerning the alleged corruption of Trading Justices contributed to the passage of the Middlesex Justices Act in 1792, effectively eliminating their role.

Detail: William Hogarth. Night. The Four Times of the Day. May 1738. © London Lives.

Detail: William Hogarth. Night. The Four Times of the Day. May 1738. © London Lives.

The "Court Justice"

Because maintaining law and order in London was so important to the government, from the sixteenth century successive governments pursued a policy of identifying a reliable justice in Westminster who could provide intelligence to the government and who could be relied on to carry out government orders. Known as "Court Justices", these Justices were financially rewarded for their efforts. Those active in the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries include:

- 1670s: Sir Edmund Berry Godfrey

- 1681-89: Sir John Reresby

- 1720s: Nathaniel Blackerby

- 1729-46: Thomas De Veil

- 1748-53: Henry Fielding

- 1754-80: John Fielding

- 1761-80: John Hawkins

Thomas De Veil, who was also accused of being a Trading Justice, received a grant of £250 from the Treasury within five years of his appointment as a Justice, and another £100 in 1740. In 1738 he was appointed Inspector-General of Imports and Exports with a salary of £500 per annum. For seventeen years he was the most active Justice in London, breaking up gangs of robbers, implementing the 1736 Gin Act, and prosecuting frauds on the revenue. But he also knew how to maintain his reputation among the public, by looking the other way when too rigorous enforcement of the law would have been unpopular. Although he was often accused of corruption, including consorting with prostitutes in return for protecting their brothels, he was never caught doing anything improper. Indeed, it could be argued that his relationships with brothel keepers allowed him to control that trade (though it also allowed the madams to have some power over him). By conducting his judicial business from an office, first in Leicester Square and later in Bow Street, he laid the foundations for some of the innovations introduced by Henry and John Fielding - his immediate successors.

When De Veil died the government found it difficult to replace him, but eventually the novelist, Henry Fielding, who served as a Justice between 1748 and 1754 (until shortly before his death), took his place. Fielding met the property qualification for serving as a Middlesex Justice through the patronage of the Earl of Bedford, and was apparently secretly in receipt of a £200 salary from the secret service fund. Although unpopular among the lower classes for his attacks on vice, his role in the hanging of the alleged rioter Bosavern Penlez in 1749, and his support of the government candidate in a parliamentary by-election, Fielding's innovations in establishing the Bow Street runners were important for the history of policing, and his Bow Street office, taken over after his death by his half-brother John Fielding, led the way in the development of pre-trial hearings.

Bridewell and Bethlem, Minutes of the Court of Governors, 1689-95, Bridewell and Bethlem Archives, Ms. BCB-16 (Box C04/3), LL ref: BBBRMG202010246.

Bridewell and Bethlem, Minutes of the Court of Governors, 1689-95, Bridewell and Bethlem Archives, Ms. BCB-16 (Box C04/3), LL ref: BBBRMG202010246.

Summary Justice

Many minor offences could be adjudicated by a single Justice, or pair of Justices, with a formal conviction and order for punishment (fine, whipping, or commitment to a house of correction) issued immediately. The Justices' powers of summary jurisdiction increased considerably over the eighteenth century, as parliament passed a series of statutes which gave them authority to make summary convictions for specified crimes.

This form of justice affected large numbers of plebeian Londoners, primarily as the accused but sometimes as plaintiffs. Summary conviction was an attractive option for Justices and plaintiffs because it was quick and inexpensive, leading to the immediate punishment of the convict. Summary proceedings also avoided the unpredictability associated with jury trials. Both masters and servants (and other employees), for example, found summary justice useful for bringing the other to account for not fulfilling their side in contracts of employment. But because magistrates were more likely to be sympathetic to masters than to servants, and because the number of statutes protecting the interests of employers increased faster than those protecting servants, summary law favoured masters rather than servants.

Plaintiffs were frequently supported by lawyers and summary convictions were easier to obtain. Moreover, these convictions were unlikely to be subject to any kind of judicial review. And in a reversal of standard legal practice, some statutes underpinning summary prosecutions presumed the defendant guilty until they could prove their innocence. In order to be acquitted of possessing stolen goods, for example, those accused of this offence had to demonstrate that they had acquired them honestly. In the eyes of the law, the relatively minor punishments inflicted for these offences appear to have justified the reduced standards of evidence needed for convictions.

Records of convictions are largely organised by the type of punishment. Certificates of conviction by fine (particularly for profane swearing and cursing) can be found in the Sessions Papers (PS), though only a portion have survived. Records of those punished in houses of correction can be found in house of correction calendars. Few records survive of punishments by whipping.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers 1718, MJ/SP/1718/10, LL ref: LMSMPS501730024.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers 1718, MJ/SP/1718/10, LL ref: LMSMPS501730024.

Offences

Of the numerous offences subject to summary conviction, those most frequently punished were various types of vice and disorderliness, including drunkenness, selling ale without a licence, permitting tippling in an alehouse, working on the Sabbath, and profane swearing and cursing. Vagrancy and idleness, disobedience on the part of servants, certain types of petty theft and embezzlement, assault, and violations of wide variety of economic and administrative regulations were also prosecuted summarily.

Unlike in some other counties, petty thefts in London were frequently punished summarily in houses of correction, which helps explain the relative dearth of such prosecutions at Sessions and the Old Bailey. Over the course of the century the passage of a number of statutes expanded the range of property offences punishable by summary jurisdiction, including several types of embezzlement from the workplace, extending even to the failure of workers to return goods lodged with them by their employers.

In the late eighteenth century a large number of assaults were heard in the magistrates' courts in the City of London, with cases normally settled informally or with the punishment of a fine. It has been estimated that perhaps one in seven households in the City were involved in assault cases at the summary courts in the late eighteenth century, ten or twenty times more cases than were prosecuted in the higher courts, but it is important to note that many of these cases involved very little actual violence, and were essentially civil cases.2 Owing to low costs and ease of access, many of the litigants were plebeians.

Under the vagrancy laws, Justices could order the punishment of beggars, "idle and disorderly" persons, people who had no means of subsistence and refused to work, and those who did not stay in the parish to which they had been removed by the settlement laws. The lack of specificity of some of these offences, notably "idle and disorderly" conduct, contributed to the passage of the 1744 Vagrancy Act, which specified that those convicted should have committed one or more specific "acts of vagrancy". Further statutes extended the definition of vagrancy to those suspected of theft and other felonies. In order to bring discretionary powers of JPs under control, the 1792 Middlesex Justices Act specified for the first time a minimum sentence for vagrancy.

Judicial Review

Justices of the Peace often interpreted their powers of summary conviction broadly, for example by defining as "petty theft" larcenies involving goods considerably over the maximum value of a shilling. In doing so, they were conscious that their actions were unlikely to be subject to judicial review. Although there were a number of legal mechanisms by which summary convictions could be challenged, they were all expensive and unlikely to be used by the people mostly likely to be subject to summary conviction, the poor. In any case, the high court judges were inclined to give Justices the benefit of the doubt, so it was difficult to have a conviction overturned.

In the late eighteenth century, however, the number of challenges increased, and the high court began to expect more evidence from Justices that the correct procedures had been followed. King's Bench judges established new standards in the conduct of summary hearings, for example specifying that the accused should have been given a chance to defend themselves. Statutes giving Justices summary powers increasingly specified the procedures which had to be followed, and allowed for those convicted to appeal to sessions.

There were at least two causes of this increasing oversight of summary jurisdiction. A change in the dominant legal culture favoured greater specificity in the conduct of legal procedures. But it is also important to recognise the important role played by challenges to summary convictions made by plebeian Londoners, including several women accused of streetwalking, a notoriously vaguely worded offence. Assisted by lawyers, who were also playing an increasing role in Old Bailey criminal trials from the 1780s, these women helped to bring to light procedural irregularities in summary convictions that became increasingly difficult to ignore.

St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 1754-60, Westminster Archives Centre, Ms. B1069, LL ref: WCCDMV362100151.

St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 1754-60, Westminster Archives Centre, Ms. B1069, LL ref: WCCDMV362100151.

Magistrates' Courts

Although many of the summary powers available to Justices of the Peace could be exercised by individual Justices at any time, others required two Justices to act together. From this arose the practice of Justices holding petty sessions, where local Justices, often grouped according to the "division" of the county in which they lived, met together to conduct business which could not be completed individually, but which did not need to be referred to a full meeting of the Justices at sessions. Among the business conducted at petty sessions were settlement and bastardy examinations, alehouse licensing, and the appointment of parochial officers. In the eighteenth century such meetings were increasingly also used for coordinating attempts to suppress vice, while a related institution, the magistrates' court, evolved for the purpose of conducting preliminary hearings of those accused of both petty and serious crimes.

In Middlesex, divisional meetings date back to the early seventeenth century. Given the large population of the metropolitan area, and its attendant social problems, it is not surprising that these petty sessions flourished in the eighteenth century. The Middlesex sessions frequently ordered Justices to meet in "their petty sessions", sometimes twice a week. In Westminster, where Justices frequently sat on the parish vestries, these petty sessions often coincided with vestry meetings, as occurred in St Margaret, St Paul Covent Garden, and St Clement Danes (the records of petty session activity for the first two parishes no longer survive). In these meetings judicial and parochial business became indistinguishable, with the Justices issuing orders about the administration of poor relief, and the other members of the vestry participating in deciding the outcomes of appeals to the Justices. References to petty sessions in the East End are more sporadic.

Detail, William Hogarth. The Industrious 'Prentice, Alderman of London, the Idle one brought before him & Impeached by his Accomplice. Industry and Idleness. Plate X. October 1747. © London Lives.

Detail, William Hogarth. The Industrious 'Prentice, Alderman of London, the Idle one brought before him & Impeached by his Accomplice. Industry and Idleness. Plate X. October 1747. © London Lives.

City Courts

In the City of London, where the ward system provided efficient local government, petty sessions were unnecessary, except with respect to criminal business and poor law appeals. For this purpose the Lord Mayor and the aldermen who were appointed magistrates were entitled to hear complaints on the same basis as any other Justice of the Peace. As the chief magistrate of the City, the Lord Mayor sat daily at his residence to hear complaints, while in the early eighteenth century some aldermen acted as magistrates in their own houses. The complaints heard by the Lord Mayor and aldermen primarily concerned accusations of theft, assault, abuse or neglect of office, swearing, nightwalking, Sabbath breaking, vagrancy and begging, and religious dissenters taken in conventicles.

But the growing reluctance of the aldermen, an elite group, to spend time adjudicating such complaints, together with the growth in the volume and complexity of such business, led to the creation, in 1737, of "the first consciously created magistrates' court in the metropolis".3 Aldermen now sat in rotation daily in the Guildhall to hear complaints arising from the western half of the City, while the Lord Mayor sat in the Mansion House (following its construction in 1753) to hear cases from the eastern half. By the late eighteenth century, the two courts were hearing around 7,000 cases a year, far more than was heard in any other criminal court, and involving potentially half of the households in the City. Most of the business concerned accusations of petty theft, violence, and regulatory offences such as disorderly conduct, traffic and Trading violations, vagrancy and begging, and prostitution. A large proportion of the business, even when the accused crimes were felonies, was settled through informal settlements and summary convictions, without referring the case to the City Sessions or the Old Bailey. And importantly, this form of justice was available to prosecutors from a wide variety of social backgrounds, including women and the poor.4

The extensive business conducted by these courts also contributed to the development of pre-trial judicial hearings, during which evidence against accused criminals was assembled and vetted; an innovation which was further developed in the hearings conducted by John Fielding discussed below. With their facilities for accommodating an audience, these hearings also contributed to making the administration of justice more public.

Records of these adjudications, known as the Lord Mayor's Waiting Books and the Mansion House Justice Room Charge Books, are available at the London Metropolitan Archives.

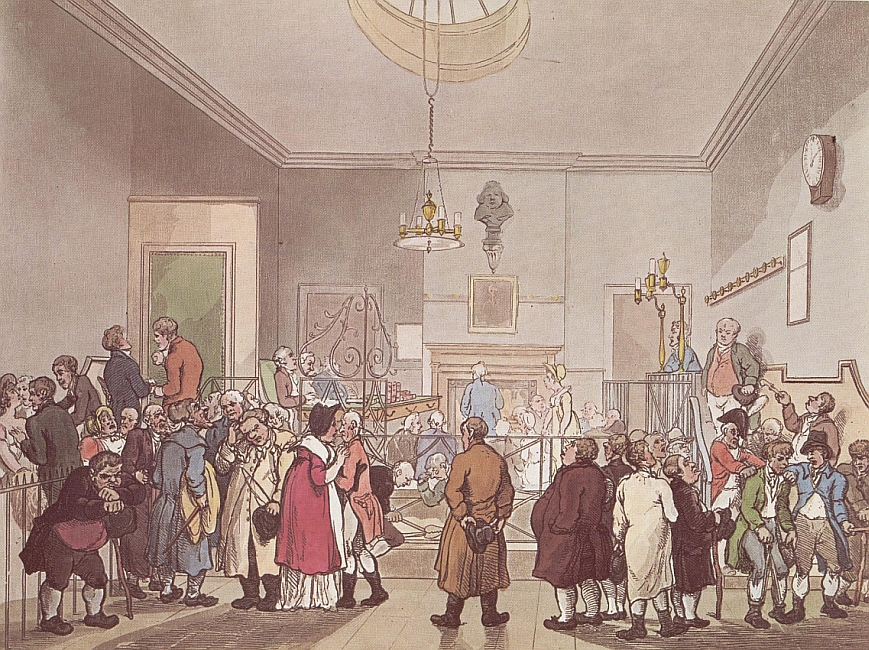

The Public Office, Bow Street magistrates office. The Malefactor's Register; or the Newgate and Tyburn Calendar (1779). 5 vols, frontispiece to vol. 3. ©British Library.

The Public Office, Bow Street magistrates office. The Malefactor's Register; or the Newgate and Tyburn Calendar (1779). 5 vols, frontispiece to vol. 3. ©British Library.

Bow Street

At about the same time that the City introduced its magistrates' court, the Court Justice Thomas De Veil started conducting public criminal hearings in an "office" in his house in Leicester Square. When he moved to Bow Street in 1740 he set up a courtroom in his house, and gained a reputation for conducting vigorous examinations of criminal suspects. Shortly after his death in 1746 the house was taken over by Henry Fielding. Between December 1748 and his departure for Lisbon in 1754 Fielding used the residence not only for hearing criminal complaints and conducting examinations, but also as a base for the Bow Street Runners.

Following Henry Fielding's departure, the Bow Street office was taken over by his half-brother John Fielding, who remained there from 1754 until his death in 1780. During this period John introduced further innovations, increasing the role played by magistrates' courts in the pre-trial process.

First, he established the Bow Street office as a central point for gathering information about crime and criminal suspects for the whole country. The office was open regular hours, and the public were invited to report all serious crimes and suspicious activities directly to the office, from which Fielding promised to promptly send out the runners in search of the culprits. Information about wanted men was also published in the press. In the 1770s Fielding started publishing lists of criminal suspects which later developed into the Police Gazette.

Second, and like his predecessors, John Fielding also conducted examinations of suspects, but he used these pre-trial hearings more proactively to vet cases, dismissing weak cases and building up the case against those who would be sent for trial at the Old Bailey. In 1768, when three magistrates served in rotation, Fielding claimed:

In 1772, Fielding built a courtroom to encourage public attendance at these hearings, and he advertised them in the press so as to encourage witnesses who could supply relevant information to attend. Defendants who were able to prove their innocence were dismissed, while those against whom he wished to build up a case were detained under the vagrancy laws and re-examined publicly in front of new witnesses. In developing these procedures, Fielding created "what was essentially a new stage in the pretrial procedure".6 It was also technically illegal, since Justices were supposed to commit all suspected felons to prison for trial by jury and not dismiss them before trial.

By 1770 these pre-trial hearings had become a major feature of criminal justice in London, with Bow Street responsible for sending a significant proportion of all the suspected felons tried at the Old Bailey. They encouraged greater participation of lawyers, both at Bow Street, where defence council were able to get the case dismissed before trial, and at the Old Bailey. In 1785, the practice of giving the accused the opportunity to answer charges at a pre-trial hearing was enshrined in law, when it was ruled in the Court of Common Pleas that accused felons should not be committed to prison for trial without a preliminary examination.

But in publicising the hearings so widely, Fielding's procedures also had the effect of creating adverse publicity against the accused which could prevent them from obtaining a fair trial. His practices were challenged in a lawsuit at King's Bench in 1780, when the attorney-general complained that press reports of hearings at Bow Street led to "crimes [being] magnified; prisoners calumniated, prejudiced, and in the minds of men convicted before hearing".7 Although the hearings continued, the press was forced to stop reporting them in such detail.

Middlesex Sessions Records, General Orders of Court Books, 1763-74, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms. MJ/OC/8, LL ref: LMSMGO556050014.

Middlesex Sessions Records, General Orders of Court Books, 1763-74, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms. MJ/OC/8, LL ref: LMSMGO556050014.

By 1792, the Bow Street office saw itself as having jurisdiction over the whole metropolis. Most felony prosecutions were heard there, particularly when initiated by public officials, including secretaries of state and Justices of the Peace.

The new judicial practices at Bow Street were imitated by Justices in other parts of the metropolis. In the late 1750s, Saunders Welch established a rotation office in Litchfield Street, and in 1763 three were established for the urban divisions of Middlesex, in Whitechapel, St Andrew Holborn, and St Giles in the Fields. These offices depended on voluntary service by the Justices, however, and they developed a poor reputation as centres of corruption. The Litchfield Street rotation office collapsed once its leading Justice, Saunders Welch, withdrew. Bow Street's innovations, however, were enshrined in law with the passage of the Middlesex Justices Act.

1792 Middlesex Justices Act

During the second half of the eighteenth century, the Middlesex Justices acquired a reputation, largely undeserved, for corruption and inefficiency. Trading Justices provided a useful service for poor Londoners who sought the arbitration of disputes without having to initiate a formal prosecution. But their relatively low social status, and the fact many depended on the income derived from their judicial activities, made them vulnerable to attack, and the over 500 per cent increase in the number of recognizances issued by Middlesex Justices from 1750 to the early 1790s looked suspicious. The government did not like the way litigants, and Justices, were using the judicial system. At the same time, growing concerns about levels of crime and disorder in the metropolis (particularly in the context of the French Revolution), and the apparent success of the Bow Street magistrates' court, provided support for reform.

An attempt to establish metropolitan-wide commissioners to supervise Justices and policing, the 1785 Police Bill, failed, largely owing to opposition by the City of London, which sought to defend its historic independence. In 1792, however, the Middlesex Justices Act (which excluded the City) was passed with little opposition, radically changing the role of Justices of the Peace in the metropolis. The Act set up seven public offices, in addition to Bow Street, to which three salaried Justices each were attached. The Justices were paid £400 a year, but were not entitled to any fees. No other Justice in the metropolis was entitled to charge fees. Six men were appointed as constables in each office, and given the power to arrest any suspected persons and reputed thieves they found on the streets. Like Bow Street, the new offices held pre-trial hearings and exercised the powers of summary jurisdiction. In 1800 an eighth office, the Thames River Police Office, was opened, with a wide jurisdiction for dealing with offences committed on the river and the riverside area; this office became the focus for the "progressive extension of police powers".8

Thomas Rowlandson, Bow Street Office, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. ©London Lives.

Thomas Rowlandson, Bow Street Office, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. ©London Lives.

Beyond the payment of salaries to Justices of the Peace for the first time and the employment of a large number of salaried constables, what was new about the system created by the 1792 Act was the extent of Home Office control over metropolitan policing. The Justices were appointed, and could be dismissed, by the Home Office. The Home Office issued instructions on how they should act, and the Justices were required to send it weekly reports.

The Act led to a vast reduction in the number of recognizances issued in Middlesex, to levels not seen since the 1750s, and was possibly responsible for a small decline in the number of trials at the Old Bailey in the 1790s. Since Justices were no longer entitled to charge fees, they may have decided not to help the poor in the way that they had done prior to 1792, or they may have continued to provide such assistance, but without initiating formal legal procedures. Because recognizances were less often issued, their actions were simply not recorded. The evidence certainly suggests that the public still sought informal judicial mediation. But public demands for justice had led to a formalisation of procedures, and the opportunities (and abuses) which resulted from individual judicial discretion had narrowed.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keywords John Fielding:

Introductory Reading

- Beattie, J. M. Sir John Fielding and Public Justice: The Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, 1754-1780. Law and History Review, 25 (2007), pp. 61-100.

- Dabhoiwala, Faramerz. Summary Justice in Early Modern London. English Historical Review, 121 (2006), pp. 796-822.

- Gray, Drew D. Crime, Prosecution and Social Relations: The Summary Courts of the City of London in the Eighteenth Century. Basingstoke, 2009.

- Landau, Norma. The Trading Justice's Trade. In Landau, Norma, ed., Law, Crime and English Society, 1660-1830. Cambridge, 2002, pp. 46-70.

- Paley, Ruth, ed. Justice in Eighteenth-Century Hackney: The Justicing Notebook of Henry Norris. London Record Society, vol. 28, 1991.

- Paley, Ruth. The Middlesex Justices Act of 1792: Its Origins and Effects. PhD thesis, University of Reading, 1983.

- Shoemaker, Robert B. Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex. Cambridge, 1991.

Online resources

- Justicing Notebook of Henry Norris

- Henry Fielding and Thomas Deveil. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-10, requires subscription).

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 Norma Landau, The Justices of the Peace, 1679-1760 (Berkeley, 1984), appendix A. ⇑

2 Drew Gray, The Regulation of Violence in the Metropolis: the Prosecution of Assault in the Summary Courts, c. 1780-1820, London Journal, 32 (2007), pp. 75-87. ⇑

3 J. M. Beattie, Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror (Oxford, 2001), p. 100. ⇑

4 For a detailed analysis of these records from the late eighteenth century, see Drew D. Gray, Crime, Prosecution and Social Relations: The Summary Courts of the City of London in the Late Eighteenth Century (Basingstoke, 2009). ⇑

5 Extracts from Such of the Penal Laws, as Particularly Relate to the Peace and Good Order of the Metropolis (1768), p. 7. ⇑

6 John Beattie, Sir John Fielding and Public Justice: The Bow Street Magistrates’ Court, 1754-1780, Law and History Review, 25 (2007), text after note 30. ⇑

7 Beattie, Sir John Fielding and Public Justice, text at note 117. ⇑

8 Leon Radzinowicz, History of English Criminal Law and its Administration from 1750 (5 volumes, 1948-90), II, pp. 391-4. ⇑