Associational Charities

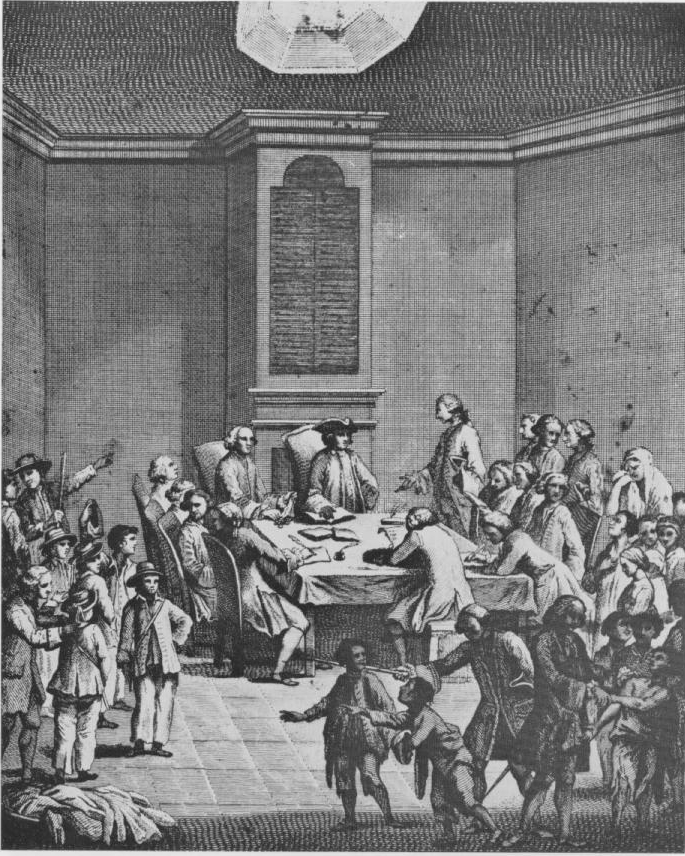

Thomas Rowlandson, The Magdalen, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. ©London Lives.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Magdalen, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. ©London Lives.

Introduction

In 1700 London possessed a centuries-long tradition of posthumous bequests creating parochial and civic charities. The charities were normally governed by the parish or other corporate bodies such as guilds. The Carpenters' Company, St Dionis Backchurch, St Botolph Aldgate and St Clement Danes all administered a large portfolio of charities, as did every other parish and guild in the capital.

But, from the second half of the seventeenth century this tradition of posthumous foundations was in decline. Concern over the poor administration of bequests, and worry that the rightful heirs of a family's fortune were being stripped of their inheritance, contributed to a marked decline in the rate at which London wills included the poor among their beneficiaries. The publication of Bernard De Mandeville's scathing Essay on Charity Schools (1723), which questioned both the motivations behind legacies for the establishment of these schools, and their impact on the children of the poor, simply added scorn to a declining tradition. And when, in 1727, Thomas Guy left his substantial fortune for the establishment of Guy's Hospital, his name was roundly cursed by commentators more sympathetic to his distant relatives who had hoped to inherit his estate than to the ill and ill-starred of London.1

In part, this decline in posthumous charitable giving was a reflection of the rise of a more activist and explicitly Protestant tradition of direct charitable engagement during life. Exemplified by the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge, with its promotion of education and the establishment of workhouses, and by the Societies for the Reformation of Manners, whose pursuit of Sabbath breakers, prostitutes and homosexuals was part of a wider religiously inspired agenda to enforce social discipline, this new pattern of social activism was most fully evidenced in the creation of Associational Charities.2

With the example of the joint stock companies that had recently revolutionised finance, and with the passage of the 1736 Mortmain Act outlawing charitable donations of land within a year of one's death, the stage was set for the creation of a new variety of charities in which the living hand of the activist took on a new role.3

Through the middle decades of the eighteenth century a slew of new-style charities were created. They were directed at specific social problems (foundling children, prostitutes, venereal disease), funded by subscription, dependent on public support and organised as associations of the living. They also used all the new tools of the emergent popular press in order to raise awareness. We have not been able to include a comprehensive set of the records of these establishments in this website (though samples from the Registers of Recruits to the Marine Society have been included), but it is important to recognise that these foundations fundamentally transformed both how individual Londoners thought about their social obligations to the poor, and how the poor interacted with the institutions of the capital. Three specific examples stand in for many more.

The Foundling Hospital

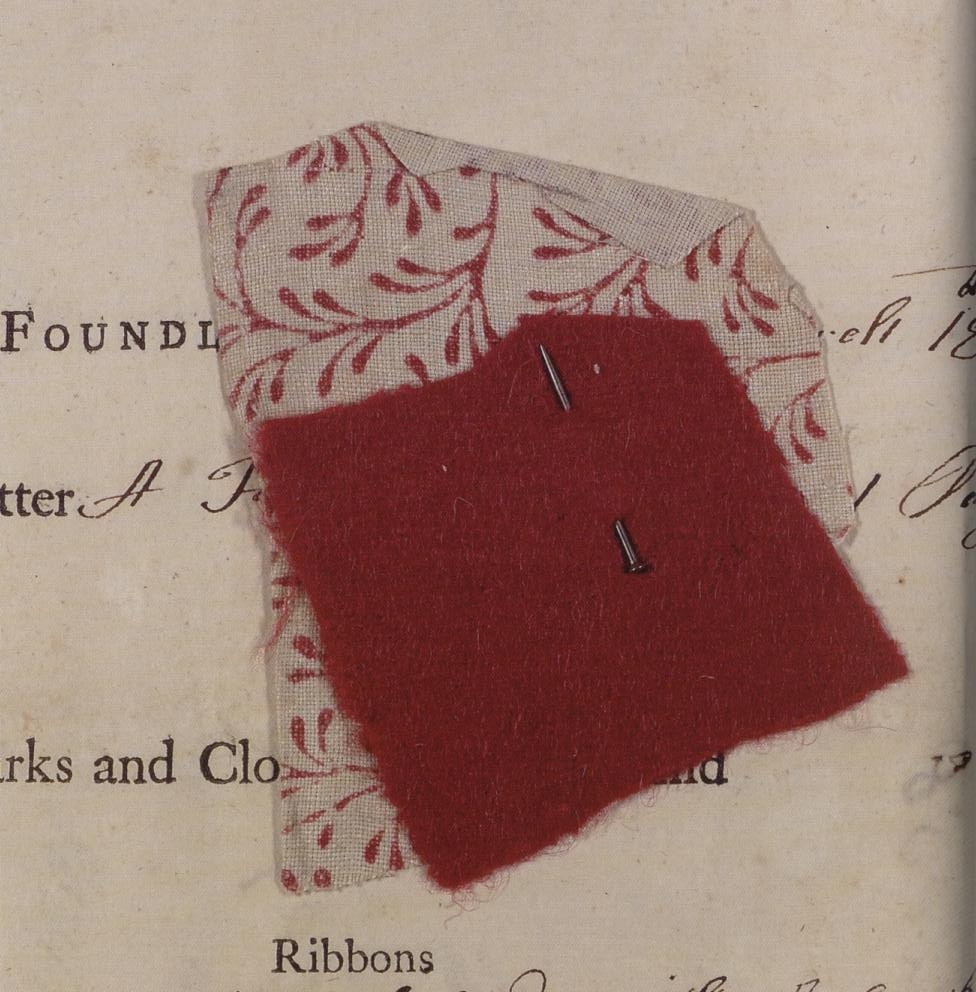

London Metropolitan Archives, A/FH/A/135, Foundling no. 12058. © John Styles and The Foundling Hospital Museum.

London Metropolitan Archives, A/FH/A/135, Foundling no. 12058. © John Styles and The Foundling Hospital Museum.

The granting of a Royal charter for the creation of the Foundling Hospital in 1739 marked the first great milestone in the creation of these new-style charities. In part a response to the plight of parish children, frequently left to the tender mercies of the parish nurses, the Foundling Hospital, grew from the vision of Thomas Coram. At the same time, the Hospital was also inspired by a desire to discipline the criminal children of the poor, and to address the problems of Blackguard children and criminal gangs. Captain Coram made a fortune as a shipbuilder in North America before retiring to London; and he campaigned vigorously for the hospital, in the face of much scepticism, through the 1720s and 1730s.4

The first foundlings (actually children delivered by their mothers or the parish) were accepted in March 1741, and by 1743, a grand neo-classical hospital had begun to rise on a site just outside the urban boundaries of the capital in St Andrew Holborn. Over the next decade and a half approximately 100 babies a year were taken in, and from 1743 sent to nurses in the countryside, before (at the age of seven) being brought back to the hospital (first occupied in 1745 and completed in 1751) for a schooling that emphasised basic literacy and industrial skills.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1753, J/SP/1753/10, LL ref: LMSMPS504220023.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1753, J/SP/1753/10, LL ref: LMSMPS504220023.

Because the Foundling Hospital and its many imitators were dependent on raising an income through annual subscriptions, they needed continually to engage the public imagination, and to promote their own activities as worthy of support. Through charity sermons and concerts, through the patronage of William Hogarth and George Frederic Handel, the hospital became a centre of social activity, as well as a working charity.

One impact of this new-model charity was to help create a new language of poverty. The children who benefited from the hospital had to be seen in the light of deserving innocence, and their support as a unproblematic social good, in order to ensure the continuing support of a fickle public. This new imperative in turn, helped to transform the rhetoric of deserving poverty, and to create a narratives to explain bastardy and female poverty as the result the immoral seduction of women by men, that was in turn embedded in British culture, and in British working-class culture in particular, over the next hundred years.

General Reception, 1756-1760

The Hospital's main impact on children and their parents came only with the advent of the General Reception between 1756 and 1760, a period during which some 15,000 infants were accepted. In these years the British government undertook to pay the Foundling Hospital to take on all infants presented to it. And many thousands were delivered up by overseers of the poor, keen to save the expense of raising a foundling child, which as in the case of a single child like Charlotte Dionis, left to the tender care of St Dionis Backchurch, could run to £160.

After just two weeks, almost 300 infants had been offered to the hospital and accepted. The startling level of demand forced the hospital to expand rapidly, creating provincial branches in Ackworth, Westerham, Shrewsbury, Aylesbury, Barnet and Chester, as well as recruiting hundreds of nurses and servants.

Over the course of the General Reception some 61% of the 15,000 infants in the Hospital's care died before the age of apprenticeship. And during the eighteenth century as a whole, the Hospital was left to bury the mortal remains of approximately two-thirds of the 18,539 children left to its well-meaning care.

When, in light of growing financial pressure and public criticism, the government withdrew its grant to the hospital, the level of intake dropped dramatically, and the Hospital's financial position became perilous. It was in an attempt to procure further government support, and to secure for the Hospital the role of parish nurse to the whole of London, that Jonas Hanway set about collecting statistics on child mortality among parish children, and promoting the passage of his Acts of Parliament requiring every parish to keep a register of the infant poor (RC).

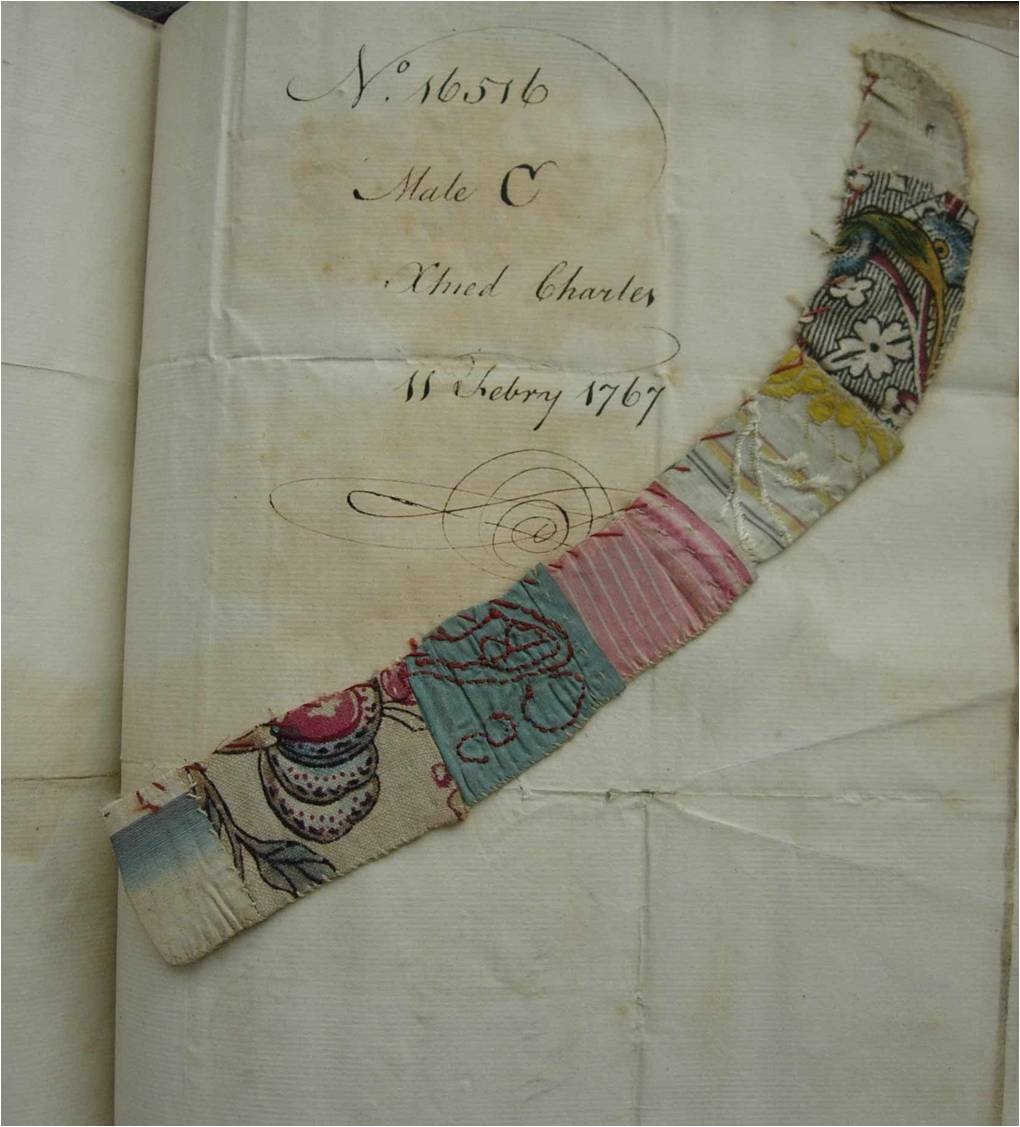

London Metropolitan Archives, A/FH/A/9/1/179: Foundling Hospital Billet Book, 1764-7, Foundling no. 16516. © John Styles and The Foundling Hospital Museum.

London Metropolitan Archives, A/FH/A/9/1/179: Foundling Hospital Billet Book, 1764-7, Foundling no. 16516. © John Styles and The Foundling Hospital Museum.

In years following the end of the General Reception the relationship between the hospital and the parents, particularly the mothers, of poor children gradually evolved. The system of Lottery that had been used to limit admissions in the period prior to the General Reception was abandoned when admissions began again in 1763. Form this date, the mothers (or parish officers or other carers), were obliged to petition the hospital for the admission of the child, laying out the nature of its circumstances, and that of the mother. The resulting petitions then formed the basis for an investigation by hospital staff. Very quickly, a new culture of petitioning evolved, in which a story of seduction and abandonment formed an important component. In the process, the Governors and the mothers of the children together helped to created a new explanation for an old social problem, bastardy and sexual incontinence, and in doing so, contributed to a substantial change in the nature of British attitudes towards gender and sexuality. At about the same time, the hospital also changed its policy towards parents attempting to reclaim abandoned children. It dropped its requirement that parents pay for the child's upkeep while it had been supported by the the hospital. As a result, to reclaim a child, all the parent was required to do from 1764, was to accurately describe the swatch of cloth or token originally left with the infant, and to petition the hospital, giving details of the parents circumstances. Between them, these changes helped to create a new space in which the mothers of primarily illegitimate children were encouraged to negotiate with institutionalised authority.5

The Foundling Hospital formed just one of large swathe of charities that took birth and the health of new-born children as soluble social problems. Lying-in hospitals were equally popular in these years, which saw the creation of the British Lying-In Hospital, established in 1749; the City of London Lying-In Hospital in 1750; and the General Lying-In Hospital in 1767. In a related development the Dispensary for the Infant Poor in Red Lion Square was established in 1769.6

The Marine Society

Just as the establishment of the Foundling Hospital was in part driven by a perceived need to address crime and poverty before they could take root, the Marine Society was also concerned with issues of crime and social disorder, and grew out of the criminal justice system. In 1756, John Fielding, now the senior magistrate at Bow Street, advertised to raise money in order to send to sea in the British Navy what he described as the "ragged and iniquitous, pilfering boys that ... infest... the streets of London". Having raised £600 through an advertising campaign, Fielding was able to send some 400 boys to a watery training in short order. In the mean time Jonas Hanway had established a charity with the related intent of clothing poor sailors. Marshalling their forces, the Marine Society came to take on Fielding's task of apprenticing children to sea service, and particularly through the course of Seven Years' War (1756-1763) used the rhetoric of boys saved from a life of crime, and of the nation in danger, to generate both large donations, and government support.7

Ragged street children transformed into useful sailors by the Marine Society. From Motives for the Establishment of the Marine Society (1757). © London Lives.

Ragged street children transformed into useful sailors by the Marine Society. From Motives for the Establishment of the Marine Society (1757). © London Lives.

Between 1756 and 1940 the Society fitted out and sent to sea some 110,000 boys. Initially, some parishes used the Society, and the authority of an earlier Act of Parliament, to off-load vagrant children. But if only because life in the Navy required a certain physicality, the Society was required to impose some restrictions on the types of children it could support. In addition to an explicit willingness to be sent, boys had to be at least thirteen years old, and 4' 3'' tall. On admission they were fed and cared for in a house on Grub Street before being marched across the South Downs to embark from Portsmouth. The sampled extracts from Registers of the Marine Society 1770-75, 1780-83, 1792-93, 1800-04 are available in the form of a data base through this site.

After the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, the Society was temporarily closed, only to recommence its activities in 1769. From this date, however, the children catered for tended to come exclusively from the settled and respectable poor, rather than from among the street urchins of London, and John Fielding later attempted to establish a separate fund for the more criminally inclined.

In many respects, the Society gradually came to take on an important function for the children of artisans and craftsmen, the settled poor. But it also generated a vociferous ideological campaign that tarred London's children with the brush of delinquency and helped to single out the children of the working poor as in need of reformation.8

The same concern to discipline London's children and to shift them from the ways of criminality can also be found in rhetoric of establishments such as the Asylum for the Reception of Orphaned Girls at Lambeth, established, again with John Fielding's involvement, in 1759. It is also evident in Jonas Hanway's related campaign to regulate the chimney sweeps of London. Like the publicity surrounding the Marine Society, Hanway's 1785 Sentimental History of Chimney-Sweepers once again retailed a series of stereotypes about the children of London, painting them in the light of an ongoing social problem, while generating a new series of narratives to explain that problem. The Philanthropic Society established in 1788 ploughed the same furrow; directing its efforts to training beggarly street children in cottage industries.9

The Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes

The Magdalen Hospital for Penitent Prostitutes grew out of the activities of many of the same men as the Foundling Hospital and the Marine Society - most particularly Jonas Hanway and John Fielding. And, as its name suggests, it was designed to provide respite and care for prostitutes; and to encourage their "reformation". Although several different proposals were published, ranging from the creation of an isolated rural retreat to an industrial establishment (favoured by Fielding) and a quasi-house of correction as proposed by the magistrate Saunders Welch, the eventual foundation took the form of an urban hospital. Following a flurry of pamphleteering by Hanway among others, a subscription was raised and the new institution opened on Prescot Street in August 1758.

The Magdalen rapidly attracted the attention of the wider social world of London, and the chapel associated with it became a fashionable resort for the well heeled. On Sundays a congregation flocked there both to hear the sermons of the ever popular preacher, William Dodd (at least up until his execution for forgery following his trial in 1777), and to gawk at the screened figures of the penitents themselves.

City scavengers cleansing the London streets of impurities!! (1816). British Museum Satires, 12814. ©Trustees of the British Museum.

City scavengers cleansing the London streets of impurities!! (1816). British Museum Satires, 12814. ©Trustees of the British Museum.

The regime emphasised silent regularity, isolation and hard work, and was almost monastic in its formulation. And in terms of its assumptions about how introspection might aid in the reformation of the criminal classes, it prefigures similar developments in the use of imprisonment for the punishment of felons.

After an early period of success in which the Hospital attracted both ready penitents and generous subscriptions, it began to fall out of favour by the 1770s, and although it survived as an institution until 1958, it heyday was in its first decade.

Like the Foundling Hospital, the Magdalen was just one of a range of institutions established to address the same broad social problem – in this case the immorality and sexual misbehaviour of women, and in consequence threatening women's ability to birth the nation.10 The Lock Hospital, opened by William Bromfield in 1747, and the later Lock Asylum for the Reception of Penitent Women, were directed at much the same audience; and these institutions themselves overlapped with the Asylum for the Reception of Orphaned Girls at Lambeth.11

Summary

Although we do not have a clear account of the volume of charity funnelled through the Associational Charities of London, they unquestionably expanded significantly the resources available to the poor. As importantly they created a newly complex variety of systems for the distribution of charity. Whereas a seventeenth-century pauper was likely to deal with his or her parish or guild to the exclusion of other sources of relief, an eighteenth-century Londoner needed to navigate a sea spotted with large and small charities of all kinds. For medical care, and the education of your children, for help in lying in, and in supporting the resulting child, an eighteenth-century pauper needed to be savvy about where they could turn.

At the same time, because the new Associational Charities were dependent upon public subscription they needed to be able to sift the wider pool of paupers to find those they could most easily present in the most sympathetic and pathetic light they could find; and to create a rhetoric of poverty that pulled most effectively at the heart strings of the middling sort.12

The result was the double-edged gift to the poor of a series of new rhetorical strategies. The seduced maid, the succourless child, the good-hearted adolescent let down by feckless parents, could all be turned to account in the daily scrabble for charitable relief. But in the process, new lines of demarcation were drawn between the recipients of charity and its donors, which in turn helped to shape the new nineteenth-century rhetorics of juvenile delinquency, the white slave trade, and a lumpen working class abandoned from all better sensibility.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keyword Foundling:

Lives using the keywords Foundling Hospital:

Introductory Reading

- Andrew, Donna T. Philanthropy and Police: London Charity in the Eighteenth Century. Princeton, 1989.

- Alysa Levene. Childcare, Health and Mortality at the London Foundling Hospital, 1741-1800: "Left to the mercy of the world". Manchester, 2007.

- Lloyd, Sarah. Pleasing Spectacles and Elegant Dinners: Conviviality, Benevolence, and Charity Anniversaries in Eighteenth-Century London. Journal of British Studies, 41:1 (2002), pp. 23-57.

- Payne, Dianne. Rhetoric, Reality and the Marine Society. London Journal, 30:2 (2005), pp. 66-84.

- Peitsch, Roland. Urchins for the Sea: The Story of the Marine Society in the Seven Years War. Journal for Maritime Research, December 2000.

- Taylor, James Stephen. Jonas Hanway, Founder of the Marine Society: Charity and Policy in Eighteenth-Century Britain. 1985.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 Donna T. Andrew, Philanthropy and Police: London Charity in the Eighteenth Century (Princeton, 1989), pp. 35-41 ⇑

2 Tim Hitchcock, Paupers and Preachers: The SPCK and the Parochial Workhouse Movement, in Lee Davison, et al., eds, Stilling the Grumbling Hive: The Response to Social and Economic Problems in England, 1689-1750 (Stroud, 1992), pp. 145-66. ⇑

3 9 George II c. 36. There is no serious secondary literature addressing the impact of the Mortmain Act, but see Gareth Jones, History of the Law of Charity, 1532-1827 (Cambridge, 1969), ch.7. ⇑

4 The most comprehensive general work on the history of the hospital remains Ruth McClure, Coram's Children: The London Foundling Hospital in the Eighteenth Century (New Haven, 1981). ⇑

5 McClure, Coram's Children, pp. 124, 139-141. ⇑

6 For a detailed analysis of the conditions suffered by children left in the care of the hospital and mortality rates, see Alysa Levene, Childcare, Health and Mortality at the London Foundling Hospital, 1741-1800: "Left to the mercy of the world" (Manchester, 2007). ⇑

7 James Steven Taylor, Jonas Hanway, Founder of the Marine Society: Charity and Policy in Eighteenth-Century Britain (1985), ch. 6. ⇑

8 Dianne Payne, Rhetoric, Reality and the Marine Society, London Journal, 30:2 (2005), pp. 66-84. ⇑

9 Taylor, Jonas Hanway, ch. 9. ⇑

10 For a complex analysis of charity, science and reproduction in this period, see Lisa Cody, Birthing the Nation: Sex, Science, and the Conception of Britons (Oxford, 2005). ⇑

11 For a detailed survey of these foundations see Andrew. Philanthropy and Police, ch. 4. ⇑

12 For an excellent account of the role of sociability in the creation of these institutions see Sarah Lloyd, Pleasing Spectacles and Elegant Dinners: Conviviality, Benevolence, and Charity Anniversaries in Eighteenth-Century London, Journal of British Studies, 41:1 (2002), pp. 23-57. ⇑