The Criminal Trial

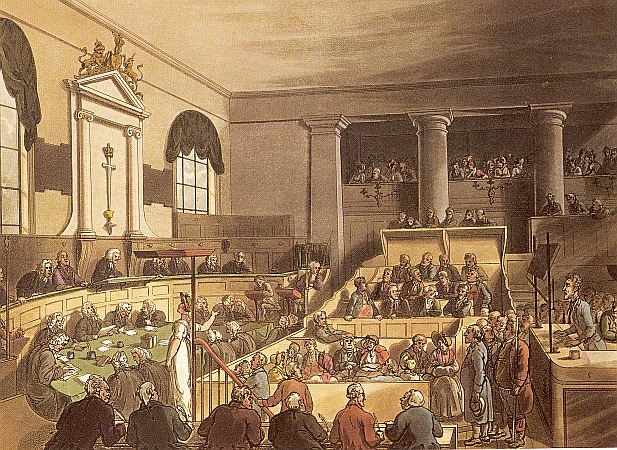

Thomas Rowlandson, The Old Bailey, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. © London Lives

Thomas Rowlandson, The Old Bailey, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. © London Lives

Introduction

Eighteenth-century criminal trials were very different from modern ones. They were quick, and typically pitted the testimony of victims and witnesses directly against the response from the accused. Until late in the century, lawyers were rarely present. Despite the fact the odds were stacked against defendants, a remarkably large number of defendants were acquitted, or convicted on a reduced verdict, reflecting the considerable discretion exercised by jurors. While trial procedures for misdemeanours tried at the sessions of the peace were fundamentally similar to those for felons tried at the Old Bailey, we have little evidence of the former, and most of the evidence contained on this page is derived from the printed accounts of trials held at the Old Bailey, the Proceedings.

Trial Procedure

Accused criminals sent for trial were either bound over to appear in court (if the offence was minor) or committed to prison (for more serious offences). Before the courts met, clerks drew up indictments laying out the formal charges against the accused, drawing on information provided by Justices of the Peace, prison keepers, and victims. This was an important stage in the process, since how the charge was framed shaped the type of punishment the accused would receive if convicted. In particular, whether the charge was a capital or non-capital offence was crucial.

At the start of the sessions, grand juries, composed of men from the middle class or above, met to decide whether there was sufficient evidence against the accused to merit conducting a trial before a trial jury. At this stage of the process only prosecutors and their victims could testify. Those cases which the grand jury approved were labelled true bills, while those rejected (a substantial minority) were labelled ignoramus and no further action was taken. The grand jury also had the right to make presentments directly charging individuals with crimes.

Defendants whose cases against them were approved as true bills were then brought into the court, formally charged, and asked to plead. At the sessions of the peace, about a quarter of those charged pleaded guilty, probably in the hope of receiving a reduced punishment. At the Old Bailey, on the other hand, where the prescribed punishment for many offences was death, the vast majority pleaded innocent. This practice was encouraged by the judges, even where guilt was certain, because holding a jury trial allowed them to find out more about the crime and therefore to determine the appropriate punishment.

Until the introduction of lawyers, each trial took the form of a direct confrontation between the prosecutor (normally the victim) and the defendant. First the prosecutor presented the case against the accused, supported by witnesses, all of whom testified under oath. The defendant, who was not put under oath, was then asked to respond, supported by any witnesses (who, from 1702, did testify under oath). Cross examination was conducted by judges, the parties, or, increasingly, lawyers. The judge then summed up, and the jury supplied its verdict. In most cases, the whole process took less than half an hour.

Trial jurors were all men, and had to meet a property qualification. By the 1730 Jury Act, jurors in Middlesex had to possess £100 in real or personal property, though in 1731 this was expanded to include leaseholders with £50. Although typically of lesser social standing than the grand jurors, trial jurors were still primarily middle class. Many served as jurors on several occasions, and had experience of office in local government, so they were familiar with the judicial process. Not precisely a jury of the defendant's "peers", the jurors were frequently from a higher social background, and often a different sex, than the defendants they tried. This, combined with the speed of trials, and the difficulty of putting together a case for the defence if they were in prison, put defendants at a considerable disadvantage in the courtroom.

For further details of trial procedures, see the Old Bailey Proceedings Online.

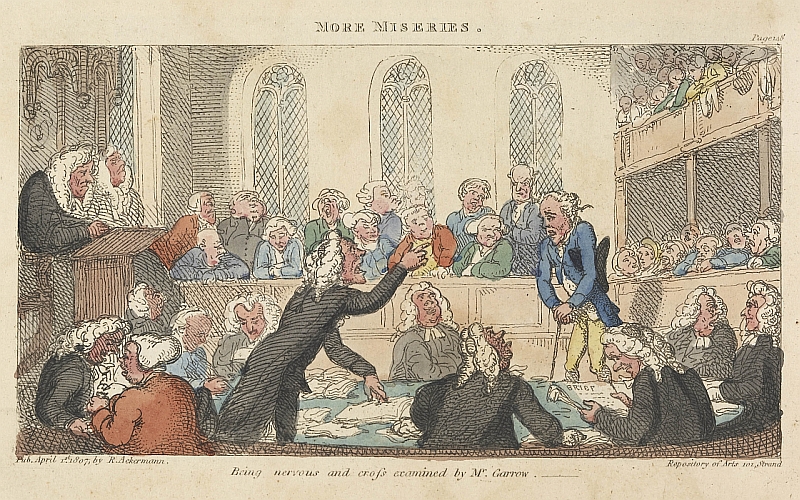

Thomas Rowlandson. More Miseries: Being Nervous and Cross Examined by Mr Garrow. 1808. British Museum, Satires 10841. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Thomas Rowlandson. More Miseries: Being Nervous and Cross Examined by Mr Garrow. 1808. British Museum, Satires 10841. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Testimonies

Over the course of the century the testimony of professional witnesses became increasingly important. These included those responsible for apprehending offenders, such as the Bow Street Runners, as well as doctors, surgeons and midwives. Although such evidence was more likely to be presented on the side of the prosecution, it was also increasingly challenged by defence lawyers, who questioned what the witness stood to gain by a conviction (where a reward was payable) or demanded high levels of certainty in the evidence presented.

Between 1730 and 1760, medical testimony was heard at more than half of the homicide trials at the Old Bailey and their testimony appears to have been given increasing weight.1 Surgeons were most common, testifying to the injuries caused by weapons and their contribution to the causes of death. Although medical witnesses appeared far more often for the prosecution than the defence, they were expected to provide disinterested evidence and not act in a partisan way. In infanticide cases, surgeons, midwives, and man-midwives often helped women obtain an acquittal by the use of the "surprise delivery" defence or by refusing to confirm that the baby had been born alive.

Unfortunately, reports of the testimony of defendants and their witnesses in the Old Bailey Proceedings were sharply curtailed compared with those of the prosecution, which makes it difficult to investigate the impact of different defendant strategies on verdicts. It is clear, however, that when testifying on their own behalf, defendants faced a difficult choice. If they robustly denied the charge, they might find that when a case amounted to their word against that of a more respectable prosecutor or professional witness, they were not believed, even when they assembled a number of respectable character witnesses to support them. An alternative strategy was to admit guilt, but plead extenuating circumstances in the hope of a partial verdict (if not acquittal) and a reduced punishment. A claim of poverty or distress, and plea for mercy, was particularly likely to help female defendants, who by presenting themselves as vulnerable could appeal to the sympathy of the male jury and judges. When made by men, however, such pleas could actually enhance juror perceptions of their guilt, and lead to a greater chance of conviction.2

Solicitors and the Pre-Trial Process

The introduction of lawyers, both solicitors preparing cases for prosecution and barristers conducting cases in the courtroom, profoundly altered the nature of the criminal trial in the eighteenth century. From the late seventeenth century, lawyers first began to participate in the pretrial process, assisting both prosecutors and defendants in preparing cases for trial. Solicitors also attended Coroner's Inquests (IC).

Solicitors, often acting as magistrate's clerks, advised victims and prepared witnesses for trial. They were first used significantly by government departments such as the Mint, the Treasury, the Bank of England, and the Post Office, to investigate and gather evidence to prosecute cases. Solicitors were also employed by prosecutors of indictments for assault, where victims often hoped to use the pressure created by a criminal prosecution to extract a payment of damages from the defendant.

The role solicitors played in advising private prosecutors and defendants opened them up to charges of encouraging vexatious prosecutions and other improper conduct. In 1681, they were accused of tampering with witnesses and packing juries.3 During the first reformation of manners campaign (1690-1738) solicitors challenged many prosecutions of prostitutes and brothel keepers on procedural and other grounds, some of which were thought by observers to be illegitimate. In 1728, an anonymous pamphlet, Directions for Prosecuting Thieves Without the Help of Those False Guides, the Newgate Solicitors, complained that solicitors advised prosecutors to engage in illegal activities such as initiating false prosecutions, compounding felonies (dropping prosecutions in return for financial compensation), bribing juries, and exaggerating evidence in order to bring offences within the scope of government rewards for conviction.4 Solicitors acting for the defence were also accused of preparing false alibis. Concerns about all these activities contributed to the judges' decision in the 1730s to allow defence counsel in criminal trials. As John Langbein has demonstrated, the "lawyerization of the pretrial facilitated [the] lawyerization of the trial".5

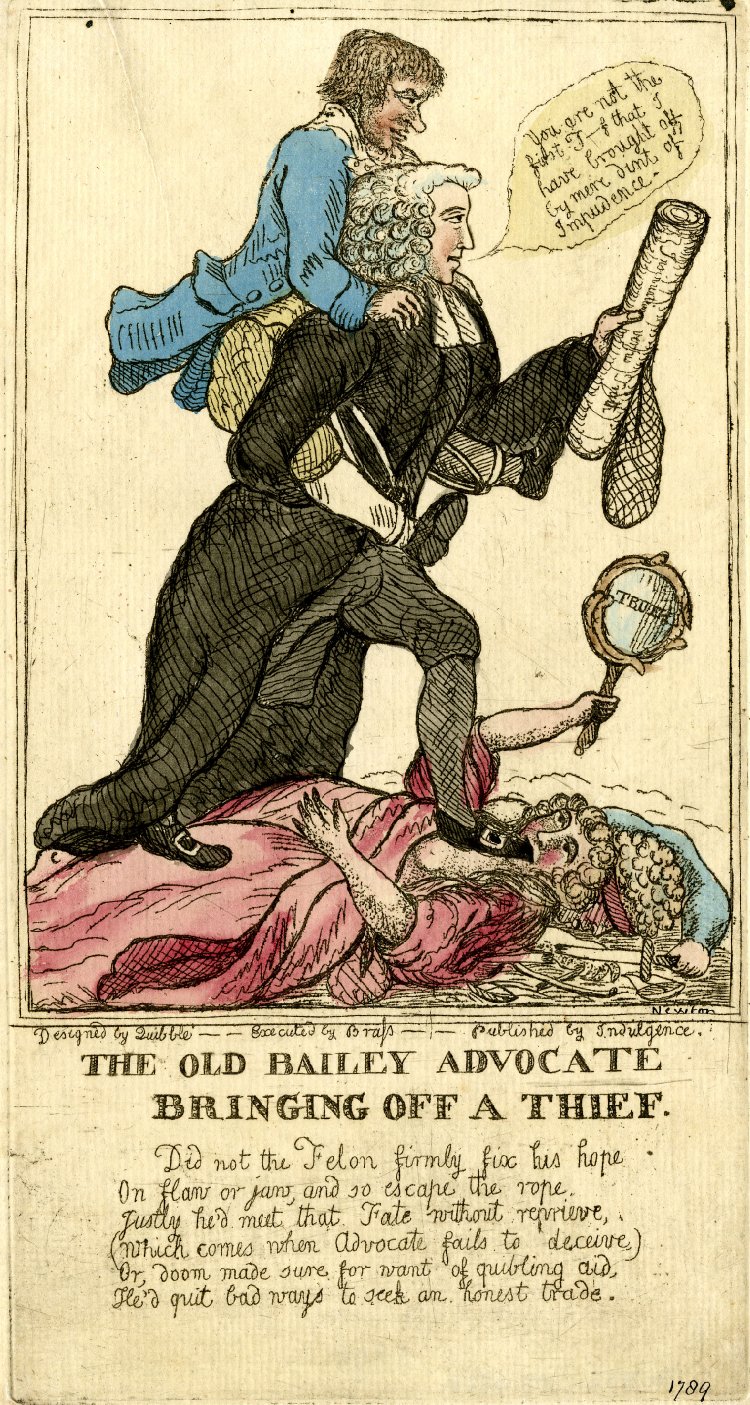

The Old Bailey Advocate bringing off a thief. 1789. British Museum, Satires 7593. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The Old Bailey Advocate bringing off a thief. 1789. British Museum, Satires 7593. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Barristers and the Criminal Trial

Although lawyers for the prosecution were allowed in all trials at the start of the eighteenth century, few prosecution lawyers were present in felony trials until the 1720s and 1730s, when their increasing use appears to have persuaded the judges to allow them to act for the defence as well, though defence barristers were not allowed to summarise the case or address the jury until 1836.

Neither prosecution nor defence barristers appeared very frequently, however, until the 1780s, when barristers appeared on at least one side in over 10% of Old Bailey trials. Their numbers further increased in the 1790s, and in 1800 they appeared for the prosecution in 21% and for the defence in 28% cent of trials. Since their presence was not always recorded, the actual number appearing was probably higher. Although they had appeared first for the prosecution in the 1720s, barristers for the defence outnumbered those for the prosecution throughout the rest of the century.6

In addition to the stimulus provided by the participation of solicitors in the preparation of cases for trial (and associated worries about vexatious prosecutions), there are a number of reasons why lawyers were introduced into the criminal trial in the eighteenth century. The initial impetus came from the government, particularly following the Hanoverian Succession in 1714. Worried about the stability of the regime and the crime wave which followed the end of the War of the Spanish Succession, the government funded lawyers to prosecute selected cases of serious crime (riot, sedition, murder, rape and violent property offences) in order to ensure that they were successful.

The presence of lawyers for the prosecution but not the defence created concerns about the fairness of the trial process, which is probably why the judges allowed barristers to appear for the defence (in a limited capacity) for the first time in the 1730s. They were probably also concerned about the increasing number of prosecutions initiated by thief-takers hoping to claim government rewards, or which relied on criminal accomplices who had turned crown evidence in order to save their lives. Both created concerns about perjured evidence, particularly in light of scandals surrounding the false prosecutions initiated by the thief-takers Jonathan Wild in 1725 and John Waller in 1732. In this context, giving defendants extra assistance to allow them to challenge problematic prosecutions must have seemed desirable.

Although thief-takers continued to be active, and raise concerns, later in the century, somewhat different reasons explain the dramatic increase in the number of counsel who appeared in trials from the 1770s to the end of the century. In the 1760s and 1770s the growth of radical politics in London, notably centred around John Wilkes, led to increased use of the law to challenge the government on a number of issues. While the criminal courts were not the focus of their activities, radical lawyers did use the courts to initiate prosecutions for murder against a Justice of the Peace and a soldier following the killing of a protester during a demonstration outside King's Bench Prison in 1768.

Changes in the penal system in the late 1770s and early 1780s, notably the increased use of imprisonment as a punishment, the introduction of the hulks, and the resumption of transportation (to Australia), together with the dramatic increase in the number of criminal trials following the Gordon Riots in 1780 and the end of the American War three years later, further contributed to the growing use of defence counsel. Those at the sharp end of the criminal justice system adopted an increasingly adversarial relationship towards the courts, challenging their prosecutors, verdicts and sentences, with and without the assistance of barristers, with increasing vigour. Most notable among the barristers who argued criminal cases at the Old Bailey was William Garrow, who in the ten years from 1783 acted in over one thousand trials, three quarters of which on the side of the defence.7 In the 1790s, further increases in the number of lawyers acting for the defence may have been stimulated by the radical political inclinations of the Recorders of the City of London who oversaw many trials at the Old Bailey.

By the late eighteenth century the practice of providing counsel to some poor defendants free of charge, combined with the relatively low charges of barristers in straightforward prosecutions, meant that artisans, labourers, servants, and even "women of the town" frequently used counsel.8

The Impact of Lawyers

Thomas Rowldandson. The Judge. c.1800. Tate Britain, T08531. © Tate Britain.

Thomas Rowldandson. The Judge. c.1800. Tate Britain, T08531. © Tate Britain.

When the judges first allowed prosecution counsel in criminal trials in the 1720s they could not have imagined that their presence would become so commonplace, nor that defence counsel would come to outnumber those for the prosecution. Even more importantly, they did not anticipate that the presence of counsel would fundamentally transform the nature of the criminal trial in England, as jurors, judges and defendants were increasingly sidelined in favour of the dominant role played by counsel. Over the course of the century challenges by counsel, predominantly for the defence, led to the adoption of more stringent criteria for the admissibility of evidence and higher standards of evidence needed for conviction. In particular, over the course of the eighteenth century the following rules were established through trials held at the Old Bailey:

- where evidence against the accused was provided by an accomplice who turned crown evidence, corroboration was required.

- confessions were inadmissible unless they were voluntary, and not made in hope of receiving favourable treatment.

- the exclusion of hearsay evidence.

- the idea that the defendant must be presumed innocent until proven guilty.

- the idea that the defendant should be proved guilty beyond reasonable doubt.

- a prohibition against self-incrimination by defendants.

These principles were developed through the practices carried out by defence counsel of aggressive cross-examination of witnesses and persistent challenges to the evidence, demanding that once a principle had been voiced in one criminal case it should be adopted in others. In the 1780s these practices became more aggressive as the number of counsel in court grew, their presence was increasingly accepted, and the accused adopted an increasingly antagonistic stance towards the courts. Consequently trials became more adversarial, and the focus of trials shifted from the defence to the prosecution as the key question came to turn on whether the prosecution had satisfactorily proved the accusation. Defendants, who had previously been the focus of the criminal trial, were encouraged to remain silent.

Arguably, therefore, the presence of lawyers in the courtroom shifted the balance of power in the courtroom towards the defendant, prompting concerns that the guilty were able to evade justice. As the magistrate Patrick Colquhoun complained in 1796, as soon as a thief is arrested, "recourse is immediately had to some disreputable attorney, whose mind is made up and prepared to practice every trick and device which can defeat the ends of substantial justice".9 One highwayman (Jerry Abershaw) called the prominent barrister William Garrow "my Old Bailey Physician". The ability of offenders such as Mary Harvey to avoid conviction for long periods with the assistance of counsel is indeed impressive. There is some evidence that those who were defended by counsel were more likely to be acquitted: over half of William Garrow's clients were acquitted, compared to just 35 per cent of all defendants in the same years.10

The evidence suggests that these developments worried the authorities, particularly after 1789 when anxieties about radicalism and social instability escalated. Concerns about the high level of acquittals, and that defendants were learning tricks for evading justice by reading printed accounts of trials, led the City of London to prohibit the publication of trials which resulted in acquittals in the Old Bailey Proceedings between 1790 and 1792.

The impact of barristers was even wider. Those who served at the Old Bailey also practised in other London courts, and also dealt with poor law appeals, vagrancy cases, and cases of debt. John Silvester, one of the most active Old Bailey counsel, regularly appeared on briefs for settlement and vagrancy cases for the 1770s.11 In the same way that these men forced legal innovations which worked to the advantage of those accused of crime, they may have shaped changes in poor law practice which helped the poor.

Verdicts

Overall, a remarkably high proportion of defendants were found not guilty throughout the eighteenth century, even before the introduction of lawyers. Between 1690 and 1800 38% of all defendants were acquitted, and a further 20% were convicted on a reduced charge. In contrast, in the nineteenth century only 23% of defendants were acquitted, and 4.5% convicted on a reduced charge. Thus only 42% of defendants in the period 1690 to 1800 were convicted on the full charge laid against them, compared to 72% in the following century.12

There are a number reasons why there were so many acquittals and partial verdicts in the eighteenth century. At a time when the death penalty was still in frequent use, jurors were reluctant to make decisions which might condemn any but the most egregious offenders to death, and this was especially true of female offenders, particularly towards the end of the century. If they felt the defendant nevertheless merited punishment, jurors could decide on a partial verdict, which would lead the convict being whipped, branded, or transported instead.

While verdicts were determined by juries, and broadly reflected the attitudes of the middle classes, there were various means by which defendants and their counsel could make an acquittal more likely. Where they were in a position to challenge the evidence, a barrister could conduct the case as discussed above. In cases where the fact they had committed the crime was irrefutable, it was possible to plead diminished responsibility. Taking advantage of the evolving language of emotion and mental instability during the century, defendants could claim, with the support of a surgeon and lawyer, that they had been temporarily insane when they committed the crime. The Justice Thomas Deveil reportedly complained that the defence of a man who had led a riot "was made for him, [which] was that at certain times he was right out of his mind… as the jury found him not guilty".13 These pleas were particularly common in infanticide cases in the second half of the century, and were usually successful.14 In fact, no one was convicted of infanticide at the Old Bailey after 1775.

Introductory Reading

- Beattie, J. M. Scales of Justice: Defence Counsel and the English Criminal Trial in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries. Law and History Review 9 (1991), pp. 221-67.

- Crawford, Catherine. Legalizing Medicine: Early Modern Legal Systems and the Growth of Medico-Legal Knowledge. In Clark, M. and Crawford, C. eds, Legal Medicine in History. Cambridge and New York, 1994, pp. 89-116.

- Langbein, J. H. The Origins of Adversary Criminal Trial. Oxford, 2003.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 Thomas Forbes, Surgeons at the Bailey: English Forensic Medicine to 1878 (New Haven and London, 1986), p. 21. ⇑

2 Lynn MacKay, Why they Stole: Women in the Old Bailey, 1779-1789, Journal of Social History 32 (1999), pp. 626-27. ⇑

3 J. H. Langbein, The Origins of Adversary Criminal Trial (Oxford, 2003), p. 136. ⇑

4 Directions for Prosecuting Thieves Without the Help of those False Guides, the Newgate Sollicitors (1728). ⇑

5 Langbein, The Origins of Adversary Criminal Trial, p. 146. ⇑

6 J. M. Beattie, Scales of Justice: Defence Counsel and the English Criminal Trial in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries, Law and History Review 9 (1991), p. 227. ⇑

7 Beattie, Scales of Justice, p. 264. ⇑

8 David Lemmings, Professors of the Law: Barristers and English Legal Culture in the Eighteenth Century (Oxford, 2000), pp. 213-14. ⇑

9 Patrick Colquhoun, A Treatise on the Police of the Metropolis (1796), p. 24. ⇑

10 John Beattie, Garrow for the Defence, History Today, February 1991, pp. 51, 53; Heather Shore, 'The Reckoning': Disorderly Women, Informing Constables, and the Westminster Justices, 1727-33, Social History, 34 (2009), pp. 409-27. ⇑

11 Allyson May, The Bar and the Old Bailey, 1750-1850 (North Carolina, 2003), p. 66. ⇑

12 Statistics calculated using the OldBaileyOnline Statistics function. ⇑

13 Memoirs of the Life and Times of Sir Thomas De Veil (1748), pp. 41-2. ⇑

14 Dana Rabin, Identity, Crime and Legal Responsibility in Eighteenth-Century England (Basingstoke, 2004). ⇑