Criminal Justice Overview

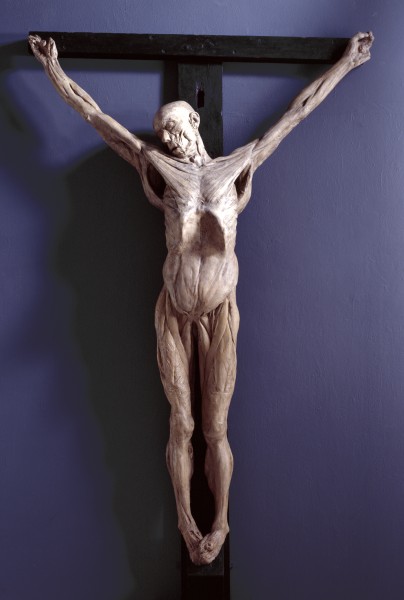

Thomas Banks, Benjamin West and Richard Cosway. Anatomical Crucifixion (James Legg), 1801. Royal Academy, 03/1438. © The Royal Academy.

Thomas Banks, Benjamin West and Richard Cosway. Anatomical Crucifixion (James Legg), 1801. Royal Academy, 03/1438. © The Royal Academy.

This page provides an introduction to the key features of criminal justice in eighteenth-century London and presents an overview of the changes which occurred over the century. It concludes with a discussion of the causes of these changes, and an explanation of how this website can shed light on them. For more detailed descriptions of the various features of criminal justice discussed here, consult the individual pages listed on the left.

Key Features

Unlike poor relief, criminal justice was a relatively centralised aspect of government, with only the appointment of constables and watchmen devolved to individual parishes. Felonies, the most serious crimes, were all prosecuted at a single court in London, the Old Bailey, though cases from the City of London and Middlesex were tried separately, by separate juries. In all other respects, criminal justice in the City of London and Middlesex were separate. Misdemeanours (lesser crimes) were tried at the separate sessions of the peace held for the City of London, Middlesex, and Westminster (a city within Middlesex). Many minor offences, particularly the petty offences of the poor, were subject to summary justice (conviction by one of two Justices of the Peace without trial) which often led to commitments to houses of correction, though depending on the offence those convicted could also be punished by whipping or a fine.

Early modern policing and criminal justice fundamentally relied on the activities of private individuals, who were variously responsible as householders for policing the streets, as witnesses and victims for apprehending and prosecuting offenders, and as Justices of the Peace and jurors for judging criminal accusations. In determining how to respond to individual cases, all these parties exercised enormous discretion in determining whether, and how, those deemed guilty of criminal acts should be prosecuted and punished. As a result, only a small minority of crimes were actually prosecuted and patterns of judicial activity were subject to considerable variation over time.

A Brief Chronology of Change

The widespread discretion exercised by all the participants in criminal justice was significantly curtailed in the eighteenth century. This was because the rapid expansion of London and the disruptions caused by economic change and frequent foreign wars led to increased concern about crime. Owing to the increased publicity generated by the expansion in printed literature which followed the expiration of press licensing in 1695, crime became a frequent topic of debate in eighteenth-century London. This stimulated many changes in public policy and in the behaviour of Justices of the Peace, those responsible for policing, and of the victims of crime.

The level of policing increased and its character changed. By offering statutory rewards for the conviction of those accused of the most serious crimes, Parliament encouraged victims and others to prosecute crimes more frequently, stimulating the development of thief-takers, who profited both from these rewards and from the fees offered by victims for the return of their stolen goods. Thief-takers soon acquired a bad reputation as "thief-makers", but Henry and John Fielding reinvented them as the Bow Street Runners and gave them a quasi-official responsibility to find and arrest the perpetrators of serious crimes. Attempts by groups campaigning for a reformation of manners to encourage private citizens to act as informers to prosecute minor offences such as vice were less successful.

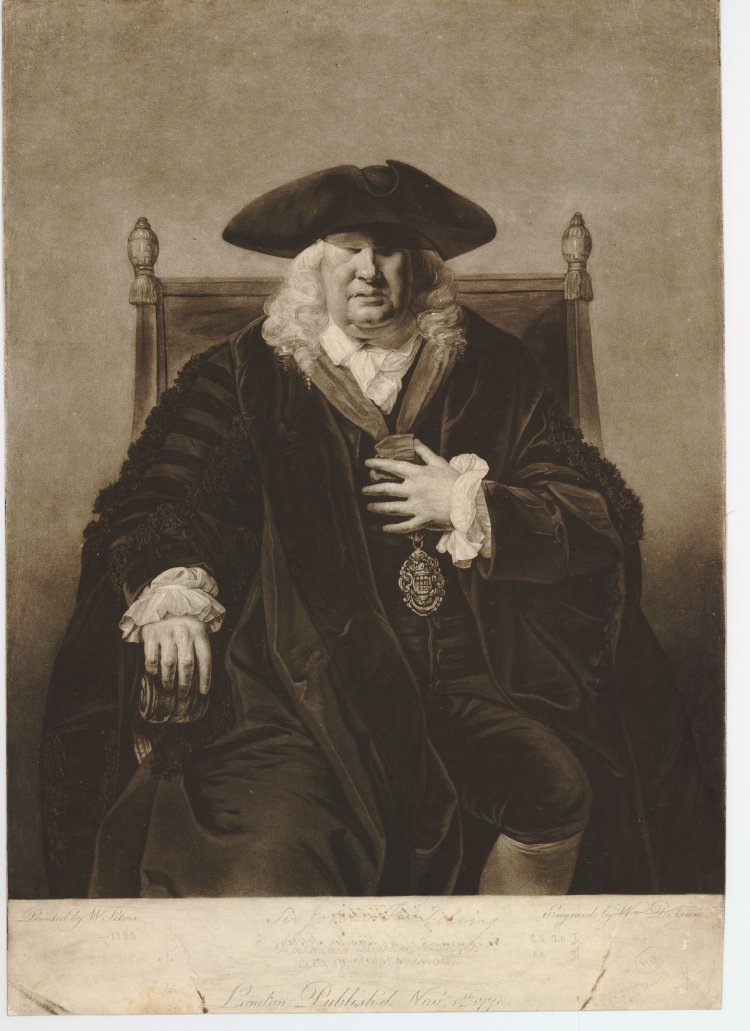

After Rev Matthew William Peters. Sir John Fielding. 1778. British Museum, Chaloner Smith 20 (undescribed state),Russell 20.I. © Trustees of the British Museum.

After Rev Matthew William Peters. Sir John Fielding. 1778. British Museum, Chaloner Smith 20 (undescribed state),Russell 20.I. © Trustees of the British Museum.

While thief-takers and informers profited from fees and rewards, for some policing and justice became a form of regularly paid employment. Many night watchmen and constables, who were previously householders serving by rotation, became full time paid officials, and their activities were more closely regulated. Similarly, following the increasing number of Trading Justices (Justices of the Peace who earned significant sums arbitrating the disputes of the poor), the 1792 Middlesex Justices Act created stipendiary Justices of the Peace, who served in one of eight public offices, staffed by salaried constables.

As a consequence of these reforms, policing became perceived as a more professional activity, and the notion that crime should be punished systematically, rather than at the discretion of victims and potential prosecutors, became more widely accepted.

The most important developments in judicial practice in the eighteenth century were the increasing use of summary justice for the punishment of minor offences, the creation of magistrates' courts for conducting pre-trial examinations of accused felons, and the growing use of solicitors and barristers by both prosecutors and defendants, which fundamentally changed the nature of the criminal trial. These developments encouraged the adoption of more precise legal definitions, more rigorous standards of evidence, and more standardised judicial procedures, some of which favoured defendants. These changes, in turn, encouraged more systematic record keeping practices, as can be seen in the more comprehensive documents found in the Sessions Papers (PS) later in the century, and the invention of a new type of record, the Criminal Registers (CR), in 1791.

These changes were also caused by the changing nature of punishment. Dissatisfaction with the death penalty, which did not seem to be serving as an effective deterrent to crime, and a desire for more effective secondary punishments, led to the adoption of transportation and imprisonment for less serious felonies and even some misdemeanours. The need to determine appropriate punishments for convicts (depending on factors such as the convict's age as well as the nature of the crime) and to keep track of convicts who had not been executed and who might return to crime contributed to the evolution of more precise record keeping practices.

Thomas Rowlandson. A Brace of Public Guardians. 1800. British Museum, BM Satires undescribed. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Thomas Rowlandson. A Brace of Public Guardians. 1800. British Museum, BM Satires undescribed. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Historiographical Perspectives

Traditional explanations for eighteenth-century criminal justice reforms identified elites as the primary agents of change. Polemicists such as Henry Fielding, John Howard, and Patrick Colquhoun, enlightened writers such as Cesare Beccaria and Jonas Hanway, and an increasingly active Parliament were given the credit for the reforms in policing, justice and punishment which were seen as inevitable steps in a Whiggish march of progress towards the modern criminal justice system. Major problems with this approach include not only the fact that many of the changes identified above predate the writings of these reformers, but also the fact that these explanations adopt an excessively top-down approach. More recent research has focused on the role of London's middle classes and broader forces of cultural change as the driving forces behind reform. Arguably, more attention needs to be paid to the pressures generated by the poor and the criminals themselves in forcing the pace (and direction) of change.

As John Beattie has demonstrated, London was in the forefront of these transformations in criminal justice because metropolitan merchants and artisans, particularly in The City but also in the parishes of Westminster and Middlesex, became deeply worried about crime in the eighteenth century, not least because they were so often victims of property offences.1 Through the participatory nature of both City government and the parish vestries, local elites were able to make changes to policing on their own terms, in ways that ensured regular street patrols while reducing their own liability to serve and keeping expenditure to a minimum. At the same time, the City of London effectively lobbied Parliament for more severe punishments of crimes such as shoplifting, and to remove offenders from the country through transportation. Because the King. his ministers, and Parliament all resided in London, the government and MPs were acutely aware of the state of crime in the metropolis, and often willing to pass criminal justice legislation, even, on occasion, when the state had to absorb to the costs of implementing the changes.

We should also, as Peter King has recently argued, pay more attention to the actions of those who actually ran the criminal justice system from the "margins"--the Justices of the Peace, jurors, clerks, and lawyers involved in individual cases who often invented important new policies, such as the differential treatment of young and female offenders and the increasing use of magistrates' courts, without reference to the central government.2

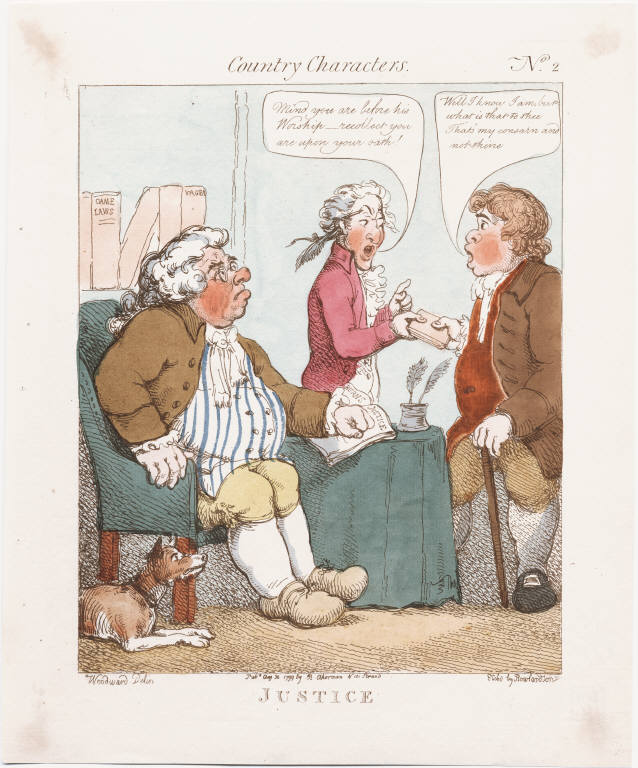

Woodward and Rowlandson. Country Characters No.2, Justice. 1799. Lewis Walpole Library, 799.8.30.2. © Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Woodward and Rowlandson. Country Characters No.2, Justice. 1799. Lewis Walpole Library, 799.8.30.2. © Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Victims and Prosecutors

In this respect, the growing pressures placed on those responsible for policing and the courts by victims and prosecutors need to be acknowledged. Victims' desires to get their stolen goods back, no questions asked, by offering rewards encouraged the development of thief-takers, while their willingness to report crimes to the Bow Street Runners ensured that this innovation would be a success. Similarly, their willingness to hire lawyers to ensure the success of their prosecutions, together with their use of thief-takers, prompted the courts to admit barristers for the defence in felony trials. The practice by poor victims of crime of taking their complaints to Trading Justices encouraged the development of stipendiary magistrates in the 1792 Middlesex Justices Act, which was passed in large part to curb the perceived abuses of Trading Justices. And the widespread practice of making vexatious prosecutions encouraged the development of increasing constraints on the use of the law, reducing the amount of discretion available to prosecutors and legal officials.

As argued by historians such as Randall McGowen and Greg Smith, all these changes were shaped by the evolving cultural context of the eighteenth-century London middle class. Expectations of order were becoming more demanding and violence was less likely to be tolerated. Consequently, those responsible for policing and punishment faced new pressures to curb violence and disorder while treating offenders in a more enlightened manner.3

Criminals and the Accused

Arguably historians have failed to pay sufficient attention to the pressures generated by criminals themselves, and those accused of crime, in shaping the evolution of criminal justice. The pressures generated by increased criminality stimulated elite fears and responses throughout the century. The crucial years when Londoners believed they were experiencing crime waves, leading to dramatic increases in the number of criminal prosecutions, were those when the demobilisation of soldiers followed the conclusions of wars, in particular 1714 through the 1720s, 1748 to 1756, and 1783 to 1793. Not coincidentally, these were periods of substantial judicial innovation, notably the 1718 Transportation Act, the creation of the Bow Street Runners in 1749, and the rebuilding of prisons and development of transportation to Australia in the 1780s (both stimulated by the sheer number of accused criminals and convicts in prison and the resulting overcrowding and disease).

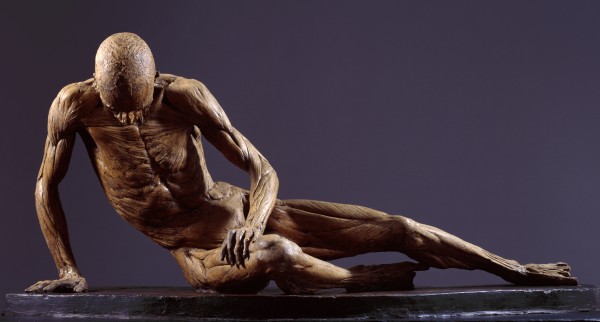

William Pink after Augostino Carlini. Smugglerius. Cast in 1834 using moulds created in 1776. Royal Academy, 03/1436. © Royal Academy of Art, London.

William Pink after Augostino Carlini. Smugglerius. Cast in 1834 using moulds created in 1776. Royal Academy, 03/1436. © Royal Academy of Art, London.

Equally, how accused criminals (increasingly assisted by solicitors and barristers) responded to their treatment by the judicial system contributed to the increasing specificity of legal practice. The options of the authorities were increasingly limited by challenges to policing and judicial authority. The use of defence lawyers limited the scope of summary justice and shaped the development of the criminal trial.

Of course, resistance, particularly in the form of riots, could have the effect of leading to innovations which strengthened policing and the state and made such resistance less likely to be effective in the future. The riots which opposed the Hanoverian accession in 1714-15 prompted the Riot Act in 1715, although it was rarely fully enforced, while the Gordon Riots in 1780 led to strengthened policing. Escapes from prisons and the hulks in the 1770s and 1780s increased the pressure for prison reform and also encouraged the renewal of transportation.

The most effective resistance occurred in the case of vice and similar victimless offences, where the goals of reformers appear to have been effectively frustrated, and their attempts to promote systematic prosecutions ultimately failed. The resistance of the accused, aided at different times by mobs, lawyers and sympathetic judicial officials, prevented reformers from developing the law into a more aggressive tool for controlling deviants. Houses of correction, for example, which were used extensively for punishing the "idle and disorderly" in the early eighteenth century, were less often used for this purpose later in the century. This resistance resulted in a narrowing of the scope of the law, in that it became clear that the kinds of sins and misdemeanours prosecuted by reformation of manners campaigns could not be systematically prosecuted.

In a sense, therefore, the substantial pressures brought by the users of the criminal justice system—both those who sought "justice" and those whose misbehaviour they sought to punish—repeatedly forced the authorities to innovate, and innovate again when those changes generated resistance and created new problems. Through the records of criminal prosecutions, appeals and decisions about policing, the records included in this website allow those pressures to be investigated in detail and the role of plebeian Londoners in the evolution of modern criminal justice to be ascertained. For advice about using these records, consult the Research Guide.

Introductory Reading

- Beattie, J. M. Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror. Oxford, 2001.

- Innes, Joanna. Managing the Metropolis: London’s Social Problems and their Control, c. 1660-1830, Proceedings of the British Academy, 107 (2001), pp. 53-79.

- King, Peter. Crime and Law in England, 1750-1840: Remaking Justice from the Margins. Cambridge, 2006.

- McGowen, Randall. The Problem of Punishment in Eighteenth-Century England. In Simon Devereaux and Paul Griffiths, eds, Penal Practice and Culture, 1500-1900: Punishing the English. Basingstoke, 2004, pp. 210-231.

- Smith, Greg. Violent Crime and the Public Weal in England, 1700-1900. In McMahon, Richard ed., Crime, Law and Popular Culture in Europe 1500-1900. Cullompton, 2008, pp. 190-218.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 J. M. Beattie, Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror (Oxford, 2001). ⇑

2 Peter King, Crime and Law in England, 1750-1840: Remaking Justice from the Margins (Cambridge, 2006). ⇑

3 Randall McGowen, The Problem of Punishment in Eighteenth-Century England, in Simon Devereaux and Paul Griffiths, eds, Penal Practice and Culture, 1500-1900: Punishing the English (Basingstoke, 2004), pp. 210-231; Greg Smith, Violent Crime and the Public Weal in England, 1700-1900, in Richard McMahon, ed., Crime, Law and Popular Culture in Europe 1500-1900 (Cullompton, 2008), pp. 190-218. ⇑