Prisons and Lockups

London Metropolitan Archives, City and Southwark Coroners' Inquests, CLA/041/1Q/02/001, LL ref: LMCLIC650010304.

London Metropolitan Archives, City and Southwark Coroners' Inquests, CLA/041/1Q/02/001, LL ref: LMCLIC650010304.

- Introduction

- Rebuilding and Reform

- Prisoners and the Making of the Modern Prison

- Borough Compter, Southwark

- Clink, Southwark

- Cold Bath Fields

- Fleet Prison

- Gatehouse Prison, Westminster

- Giltspur Street Compter

- Horsemonger Lane Gaol

- Hulks

- King’s Bench

- Ludgate

- Marshalsea

- Newgate

- New Prison

- Poultry Compter

- Savoy

- Surrey Gaol

- Watchhouses

- Wellclose Square

- Whitechapel Debtors' Prison

- Wood Street Compter

- Introductory Reading

- Footnotes

Introduction

When Daniel Defoe published his Tour thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain (1724-26), he reported that there were twenty two "public gaols" and many more "tolerated prisons" in London.1 The city was awash with places for confining prisoners, whether they were arrested for debt, petty crime, or serious crime. Most were run along commercial lines, though the fees charged were regulated by Justices of the Peace and others. Throughout the eighteenth century there were repeated scandals concerning the treatment of prisoners, and as penal principles changed and expectations increased towards the end of the century substantial efforts were made to rebuild prisons and reform conditions.

Following a section on the reform and rebuilding of prisons, this page describes, in alphabetical order, the most important individual prisons and lockups in London. For more general information about the role of imprisonment in eighteenth-century penal policy, and the growing use of imprisonment for the punishment of felons in the late eighteenth century, see the Punishment page.

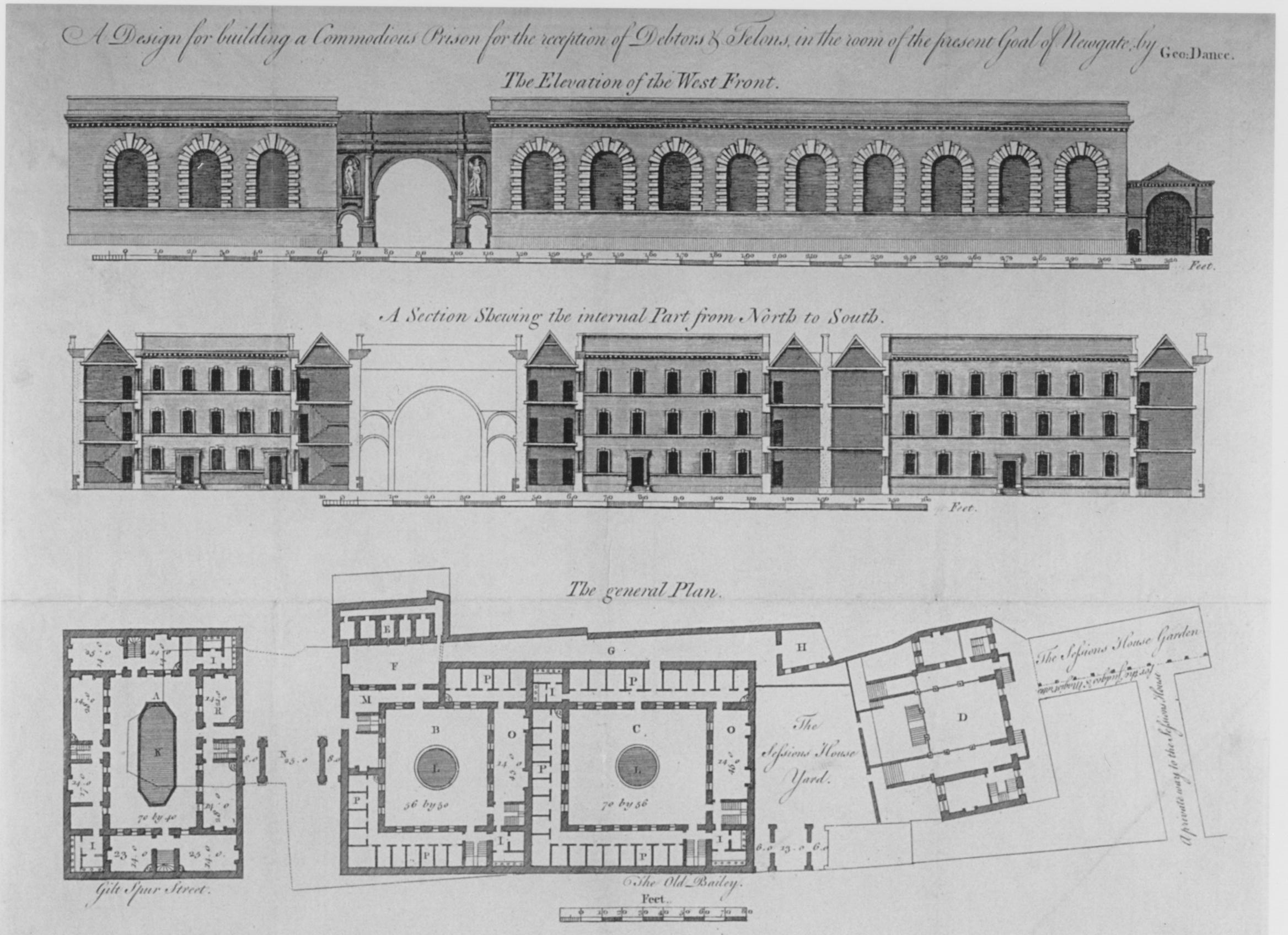

George Dance senior, West elevation, section from north to south and ground plan of Newgate Prison, Old Bailey'. c.1759. © City of London.

George Dance senior, West elevation, section from north to south and ground plan of Newgate Prison, Old Bailey'. c.1759. © City of London.

Rebuilding and Reform

While the late eighteenth century is widely recognised as a period in which a substantial amount of prison rebuilding took place, London prisons experienced change throughout the century as a consequence of a series of parliamentary statutes and local government decisions which sought to regulate existing prisons and facilitate their repair or rebuilding. As early as 1698, the Gaol Act gave Justices of the Peace the responsibility for repairing and building county gaols and dictated that those accused of murder and other felonies should be held in those gaols (rather than in private lockups).2 Occasional parliamentary investigations, such as the ones conducted into the Fleet and Newgate prisons in 1729, led to prohibitions of the sale of prison offices and other reforms.

The pace of reform quickened, however, in the 1770s. Following the publication of an English translation of Cesare Beccaria's Of Crimes and Punishments in 1767, which argued that punishments should attempt to reform the mind and not the body of the criminal and be proportionate to the severity of the crime, there was renewed interest in the reformative potential of imprisonment. In the 1770s Jonas Hanway argued that, if prisoners could be put to hard labour, kept in solitary confinement and subject to religious instruction, imprisonment had the potential to reform offenders. At the same time prison investigators called attention to the poor conditions in many existing prisons. John Howard's published account of his prison visits (The State of the Prisons, 1777) called attention to the insanitary and crowded conditions of many prisons, and in 1774 the Health of Prisoners Act mandated the appointment of a surgeon or apothecary for each prison, and the creation of separate prison infirmaries for men and women.3

In response to all these concerns, and to the interruption to transportation in 1776 which placed extreme pressure on the prisons, the Penitentiary Act was passed in 1779.4 This act authorised the building of one or more national penitentiaries and increased the length of sentences at hard labour. Although these prisons were never built, the Act stimulated further interest in prison reform and influenced the design of new prisons built in the 1790s, as explained below.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions Papers, February 1780, MJ/SP/1780/2, LL ref: LMSMPS507220072.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions Papers, February 1780, MJ/SP/1780/2, LL ref: LMSMPS507220072.

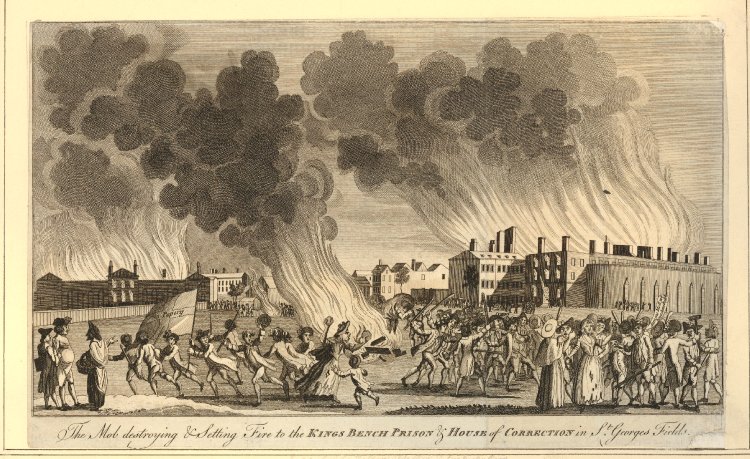

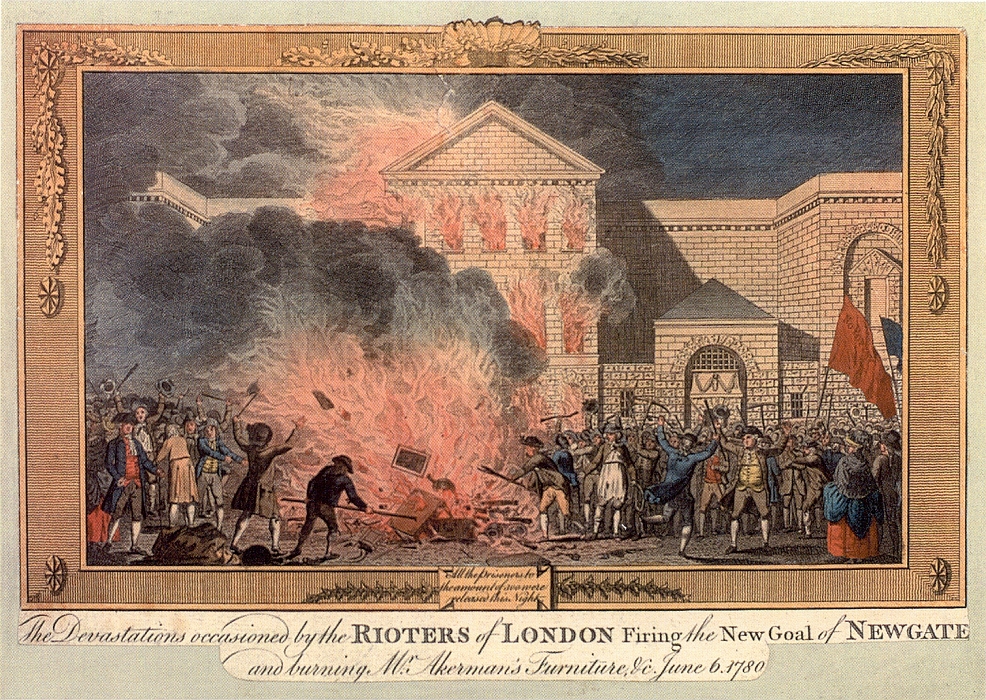

In 1780, perhaps reflecting widespread popular anger about prison conditions, the Gordon Riots resulted in the destruction of at least eight London prisons and houses of correction: Newgate, the Fleet, Clerkenwell House of Correction, New Prison, Surrey House of Correction, the Clink, King's Bench Prison, and the Borough Compter. All but the Clink were immediately rebuilt. Reflecting both the urgency with which the rebuilding took place and the fundamentally pragmatic approach of most magistrates, however, there were few changes to the design of these buildings.

But further reforms came in 1784, with the passage of an act which required regular inspections of county gaols, the segregation of prisoners by category, and the creation of separate infirmaries, chapels, and baths. Gaolers were to be paid salaries and not live off the fees charged to prisoners, and liquor and gambling were prohibited.5

A series of prisons built in London in the 1790s according to the plans set out in the Penitentiary Act demonstrates just how much had changed over the course of the century. Coldbath Fields, the Giltspur Street Compter, and the Horsemonger Lane Gaol all segregated prisoners according to sex and category of offence, put prisoners to hard labour, provided separate cells for felons and included high levels of surveillance by prison officers.

Prisoners and the Making of the Modern Prison

As the above narrative suggests, accounts of prison reform can easily be told from the top down, ascribing the impetus for change to reform ideologies, heroic prison visitors, parliamentary statutes, and the decisions of magistrates. But this is only part of the story. Given the reluctance of many of those in government to spend money, it took the actions of the prisoners themselves to force the pace of change.

The simple fact of the growth in the number of prisoners, even before the interruption to transportation in 1776, and the consequent overcrowding, frequent escapes, and disease made some kind of rebuilding inevitable. While a number of political factors contributed to the passage of the 1779 Penitentiary Act, for example, the most pressing reason for its passage was clearly stated by William Eden: "the fact is, our prisons are full".6 Given its potential to spread beyond the prison walls, as occurred when the judges in the Old Bailey courtroom were struck down in 1750, fear of the spread of contagious disease was a particularly strong motivation for reform. Prisoners' persistent demands for medical care thereby acquired a new force.

The fact that prisoners largely ran their own affairs inside prisons added to the pressure for change, both because prisoners knew how to make complaints which would excite the attention of the government (complaints of extortion and mistreatment by prison keepers were particularly effective) and because the alternative political culture of the prisons came to be seen as a challenge to the authorities. At the same time, improvements were often effectively resisted by prisoners as well as prison officers, both of whom sought to protect their traditional privileges, identities and customs.7

Prisoners were thus not merely the passive recipients of prison reform; in their numbers and by their actions they forced the pace of change and shaped its direction.

Borough Compter, Southwark

Located on the Borough High Street until 1717, and then on Tooley Street, this prison was used to hold debtors and accused criminals who were arrested in Southwark, south of the river. The prison catered primarily for debtors: in 1776 it held fifteen debtors and only one felon, and when it was rebuilt in 1787 it had accommodation for twelve felons and fifty debtors. There were complaints early in the century that the keeper extorted fees from the prisoners, and later that male and female debtors were not separated.

Clink, Southwark

Originally used principally for religious prisoners sentenced from the court of the Bishop of Winchester, in the eighteenth century the Clink acted as the local gaol for Southwark, holding a small number of debtors and minor offenders. Following its destruction in the Gordon Riots in 1780 it was not rebuilt.

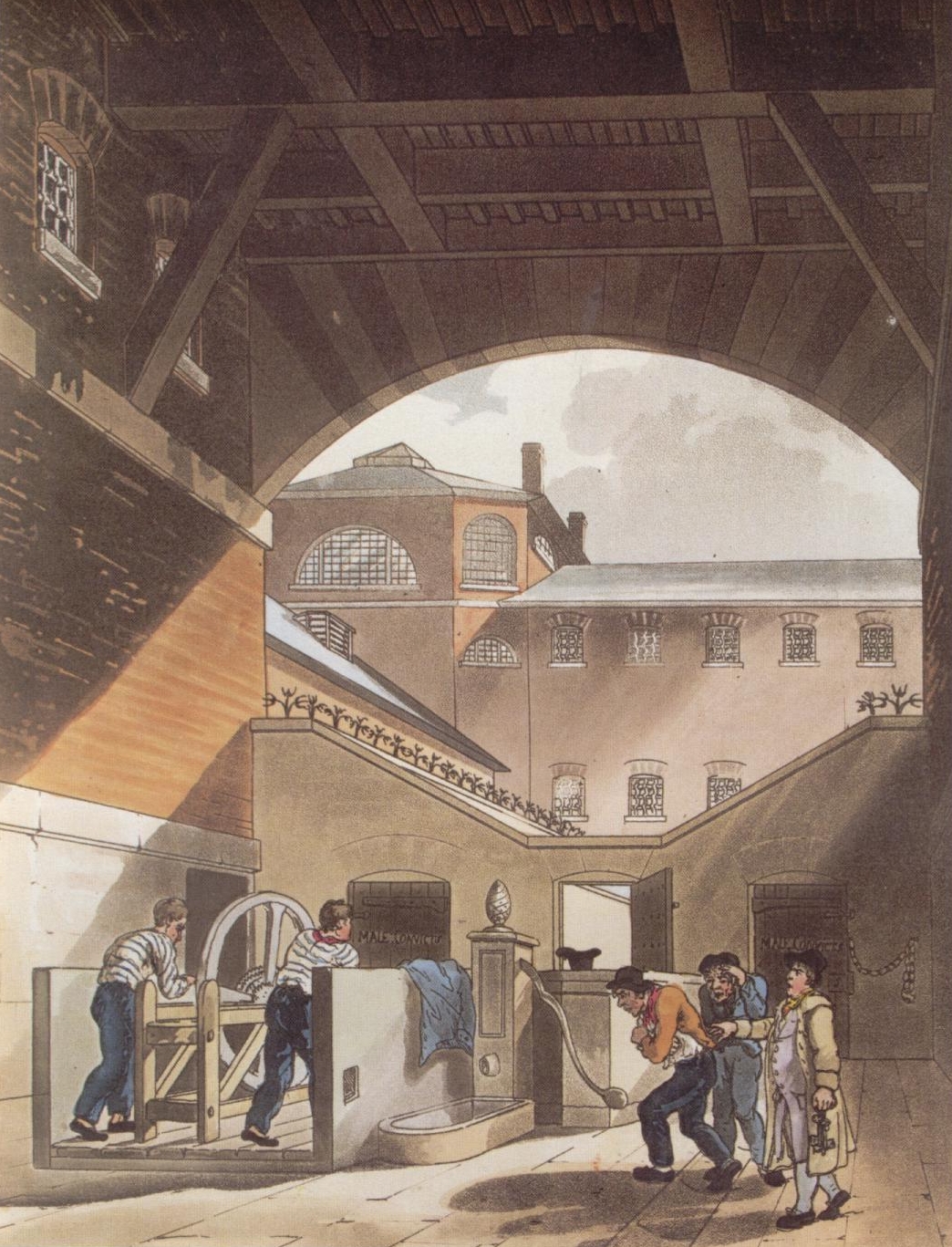

Thomas Rowlandson, Coldbath Fields Prison, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. ©London Lives.

Thomas Rowlandson, Coldbath Fields Prison, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. ©London Lives.

Cold Bath Fields

Built in 1794 according to the designs provided in the 1779 Penitentiary Act, this house of correction held 384 prisoners of both sexes. It had 232 single cells and radial wings consisting of two stories of sleeping cells above a vaulted ground floor. The prisoners were provided with an infirmary, religious instruction and employment. The use of solitary confinement in order to force prisoners to reflect on their sins proved controversial, however, and there were complaints that inmates suffered from cold, hunger and abuse.

Fleet Prison

Located next to the Fleet River in the City of London, the Fleet was a debtors' prison, not just for those arrested in London but also for those imprisoned elsewhere in the country who were transferred there under a warrant from the high courts. Like most debtors' prisons, within the walls it was a relatively free community of more than 300 prisoners, run by a prisoners' committee. The small number of officers who ran the prison had little power to regulate internal conditions, and most did not even have access to the prison at night. Wealthier prisoners stayed on the master's side, where they had their own rooms and lived in relative luxury, while the poor prisoners lived in squalid conditions on the common side, and depended on prison charities for survival.

In 1729 complaints about oppressive practices by the keeper, Thomas Bambridge, led to the formation of a Parliamentary inquiry into his government of the prison. The committee's report found him guilty of extorting money from prisoners, and blamed the abuses on the system of making keepers purchase their office, which required them to charge substantial fees to the prisoners. Bambridge was also accused of torturing prisoners and was tried for murder and acquitted. He was subsequently also tried for the theft of a prisoner's goods and acquitted. Nonetheless, Bambridge was dismissed from his office and new rules for future keepers were drawn up which included a prohibition on the sale of prison offices.

The Proceedings at the Sessions of the Peace, and Oyer and Terminer, for the City of London and County of Middlesex. December 1729, LL ref: t17291203-48.

The Proceedings at the Sessions of the Peace, and Oyer and Terminer, for the City of London and County of Middlesex. December 1729, LL ref: t17291203-48.

The Fleet was rebuilt between 1770 and 1774, but when the prison reformer John Howard visited it in 1778 he found it crowded and dirty. The prison was destroyed in the Gordon riots in 1780, though the prisoners were warned in advance so they could remove their goods before the rioters set fire to the prison. Rapidly rebuilt, in the early 1790s there were once again complaints about the prison being in poor repair and escapes. Because the prisoners were debtors rather than criminals, this was not one of the prisons affected by the late eighteenth-century reform movement, and in 1814 the Fleet was described as "the largest brothel in the metropolis".8

It was not only the keeper who was accused of abuses. Indeed, there were complaints that some of the wealthier prisoners exploited the debt laws by moving into the prison, where they could live in comfort, in order to escape their creditors. Fraudulent tradesmen allegedly entered the prison and then took advantage of the periodic insolvency acts to gain their release with their debts cleared. Some debtors imprisoned elsewhere deliberately obtained writs which allowed them to be committed to the Fleet, a more salubrious prison compared to provincial prisons. Similarly, it was alleged that some prisoners used writs of habeas corpus to move between prisons so that they could spend their winters in the warmer Fleet, and their summers in more airy King's Bench prison south of the river. For the resourceful debtor, the Fleet provided a valuable route to survival.

Gatehouse Prison, Westminster

The Gatehouse held those accused of felonies and petty offences who were awaiting trial in Westminster, as well as, owing to the presence of the royal palace and Parliament nearby, state prisoners. The prison was vulnerable to escapes, and in 1749 was stormed by twenty-four armed Irishmen who released a member of the gang who had been accused of pickpocketing.9 It was pulled down in 1776 and the prisoners transferred to Tothill Fields.

Giltspur Street Compter

Located close to Newgate Prison in the City of London, this prison was built on reformed principles in 1791 in order to replace the Poultry Compter and the Wood Street Compter. Intended to hold 136 prisoners, the prisoners were divided into four classes: debtors, felons, petty offenders, and those charged with assault. There were rows of cells for felons, separate buildings for male and female debtors, and separate rooms for those apprehended by the night watch. Despite the aspiration to keep prisoners divided by classification, in practice inmates were moved around the prison regardless of their class according to the space available.10 In this sense, the prison "marked a perpetuation of the existing regime".11

Horsemonger Lane Gaol

This was the county gaol for Surrey, located near St George's Fields outside Southwark. Built in 1792-99, it was a model prison, with 177 cells in three wings for petty criminals, and a fourth wing for debtors. A control keeper's house oversaw eight separate courtyards, allowing the prisoners to be both separated by sex and offence (felons, petty criminals, debtors) and constantly watched. Two surgeons attended.

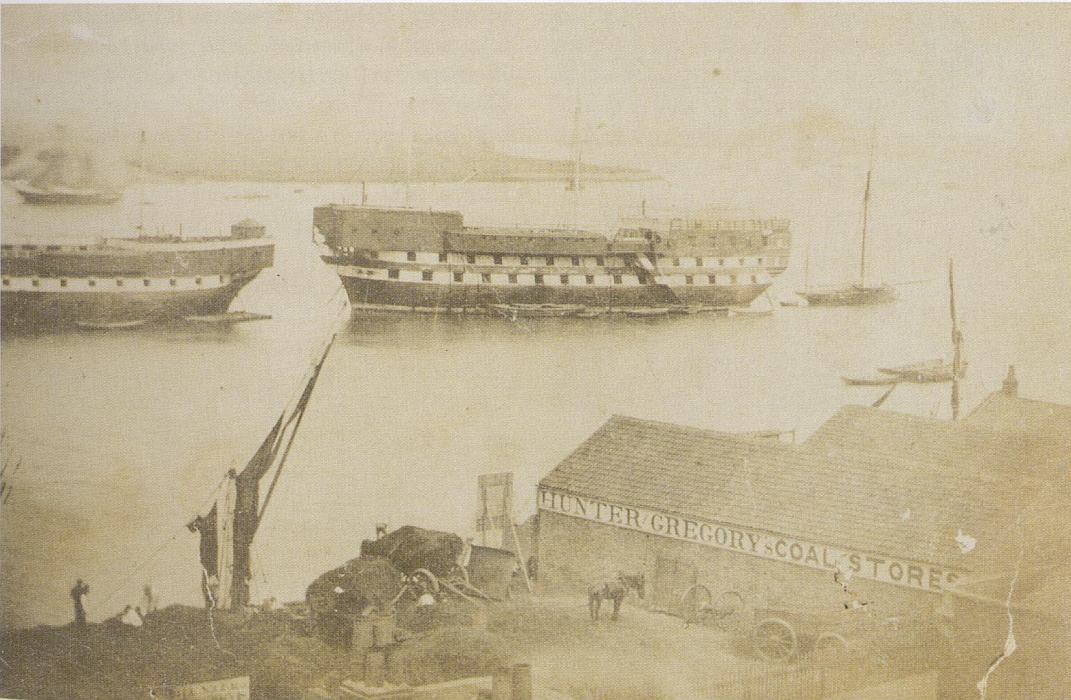

Prison Hulks on the River Thames, Woolwich, c.1856. © Greenwich Local History Library.

Prison Hulks on the River Thames, Woolwich, c.1856. © Greenwich Local History Library.

Hulks

Created following the 1776 statute which ordered that male prisoners sentenced to transportation should be put to hard labour improving the navigation of the Thames,12 the hulks were an emergency measure to cope with prison overcrowding following the interruption to transportation caused by the outbreak of war with America. The London focus of the act is evident in the fact the work took place on the Thames, and the influence of reformist principles can be seen in the fact that prisoners were put to hard labour and subjected to restrictive discipline. The first ships, the Justicia and the Censor, took on their first convicts in August 1776. The hulks were run by contractors, overseen by the Middlesex Justices of the Peace.

There were difficulties from the start. Crowded and insanitary conditions led to a high mortality rate (from August 1776 to April 1778 176 of 632 prisoners on board died), largely due to gaol fever (typhus).13 Belatedly medical treatment was provided, from 1779 in a separate hospital ship. There were mutinies, and many prisoners escaped from the work parties on shore. Problems with prisoner morale led the authorities to offer pardons to well-behaved prisoners; this practice also addressed the problem of overcrowding.

Despite attempts to address these problems, the hulks remained crowded and expensive, and in a sense contributed to the very phenomenon of criminal intransigence they were meant to solve. Their presence led to pressure for the resumption of transportation, but even after transportation was resumed the hulks remained, to be used as a place for confining and punishing prisoners prior to the departure of the transport ships. During the first twenty years, 8,000 prisoners spent time in the hulks.

The Mob destroying & Setting Fire to the Kings Bench Prison & House of Correction in St Georges Fields. c.1780-85. British Museum, Crace XXXIV.40. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The Mob destroying & Setting Fire to the Kings Bench Prison & House of Correction in St Georges Fields. c.1780-85. British Museum, Crace XXXIV.40. © Trustees of the British Museum.

King’s Bench

As a debtors' prison, King's Bench was largely run by the prisoners themselves, with conditions for individual prisoners depending largely on how much they were able to pay. There were persistent complaints of overcrowding and extortion by prison officers. In 1754, a Parliamentary inquiry prompted by a petition from the prisoners found mistreatment, misbehaviour and overcrowding, and led to an act authorising the building of a new prison. In 1758 the new building in St George's Fields, Southwark, opened (the site was chosen for the fresh air), with 224 rooms and an open courtyard. Despite its size, the prison was soon overcrowded. The open ground outside the prison provided a place for protesters to gather, as occurred when John Wilkes was imprisoned there in 1768 for libel. Radicalism spread inside the prison in 1770-71 when the prisoners campaigned for the abolition of imprisonment for debt and against the prison governors. In 1773 the Marshall petitioned the House of Commons for additional space, noting that there were no rooms for sick prisoners, nor to keep separate the small number of prisoners committed for "capital or high crimes and offences" (who therefore found it easy to escape). The prison was finally enlarged in 1780, shortly before it was entirely destroyed in the Gordon riots, after which it was rebuilt in the same form. In 1792 the Keeper demanded further repairs, in order to prevent escapes and "keep off the mob in case of riots".14 By the end of the century prison officers were apparently governing the prison more closely, but the prison was still known in the early nineteenth century for the laxity of its rules.

Ludgate

Originally one of the gates in the Roman wall of the City of London, this was used mainly for debtors, but also for petty offenders who were freemen of the City, clergy or attorneys. Prisoners elected the warden and essentially ran the prison. In 1760 when the City walls and gates were demolished, the prisoners were moved to a section of the London Workhouse in Bishopsgate Street.

Marshalsea

A debtors' prison, the Marshalsea was also used for smugglers and those who owed customs and excise fines. Like other debtors' prisons, there were complaints about mistreatment of the prisoners, and the fact that, although required by law, coroners' inquests were not held when prisoners died in the prison. Essentially in competition with the Fleet and King's Bench prisons for the business of wealthier debtors, the Marshalsea lost out in the late eighteenth century owing to its poor state of repair.

George Dance the younger. Newgate Prison. © Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

George Dance the younger. Newgate Prison. © Sir John Soane’s Museum, London.

Newgate

The principal prison for holding those accused of serious crimes in the metropolis, Newgate was part of the city wall on the western side of the City of London, next door to the Old Bailey courthouse. In addition to male and female felons, who were generally kept in irons and whose numbers swelled before each meeting of the court, there were separate wards for male and female debtors, both master's side (for those able to pay for their accommodation) and common side. As with most debtors' prisons, the master's side could be very comfortable, but the common side was "hell".15 Despite the separate wards, prisoners could mix freely with other prisoners and visitors.

Rebuilt after the great fire of 1666, the prison was five stories high. In 1726-28, when the prison was extended and the total capacity increased to 150 prisoners, fifteen cells for condemned prisoners were added in order to allow them a period of solitary reflection before their executions. The remaining prisoners were held in large wards; in the mid eighteenth century there were thirteen common wards and four master's wards.

London Metropolitan Archives, London Sessions Papers, July 1777, CLA/047/LJ/13/1777, LL ref: LMSLPS150880094.

London Metropolitan Archives, London Sessions Papers, July 1777, CLA/047/LJ/13/1777, LL ref: LMSLPS150880094.

Like most eighteenth-century prisons, prisoners' fees paid for running the prison, and much of the day to day government, following the practice at Ludgate, was performed by the prisoners themselves. At the start of the century the prison was run by four partners, prisoners appointed by the keeper, but in 1730 these were replaced by elected officers, who were responsible for enforcing discipline. Garnish, a fee paid by each prisoner on their arrival, continued throughout the century despite the fact it was a source of frequent complaints. Those who could not afford to pay garnish had to surrender their clothes.

Newgate was frequently overcrowded, particularly just before meetings of the Old Bailey court, and poor sanitary conditions meant that disease was rife, with mortality rates particularly high in winter. In 1726 gaol fever killed eighty-three prisoners, and in 1750 the prisoners brought the fever into the Old Bailey courtoom, leading to sixty deaths, including the Lord Mayor. This disaster led to immediate consideration of plans for rebuilding the prison, though that would not be achieved for almost thirty years. Although ventilators were added in 1752, between 1755 and 1765 132 prisoners died. Overcrowding also contributed to frequent escapes, most notably that of Jack Sheppard in 1724.

The first stones of a new prison were finally laid in 1770. Opened fully in 1778, the new building had separate quadrangles for debtors, male felons, and women felons. (The use of courtyards to provide fresh air for inmates can also be found in eighteenth-century hospitals such as St Thomas's.) The building held 300 male felons, 60 female felons, and 100 debtors, and included an infirmary. The lack of individual cells for prisoners demonstrates the limited impact around 1770 of contemporary reformist discourses which would radically shape prison building in the 1790s. Shortly after the building was finished it was completely destroyed by the Gordon Riots in 1780. The rioters' support for the prisoners is evident in the fact that they struck off the irons of the felons who were liberated and prevented the authorities from recapturing them. Popular hostility to the prison can also be seen in the fact that chains from the prison were paraded in triumph the next day. This triumph, however, was short-lived, and the prison was rebuilt to the same design and completed in 1783.

The Burning and Plundering of Newgate & Setting the Felons at Liberty by the Mob. © London Metropolitan Archives.

The Burning and Plundering of Newgate & Setting the Felons at Liberty by the Mob. © London Metropolitan Archives.

Attempts to reform conditions in Newgate met with little success. In the 1750 a ban on the sale of spirits in the prison was circumvented by visitors who smuggled them in. A 1774 Act which specified rules for cleanliness and ventilation in response to problems with gaol fever was "almost a dead letter".16 Similarly ineffective were the 1784 Act requiring the classification of prisoners and a 1791 act requiring regular visitations of the prison. In the 1780s the sheriffs sought to introduce new regulations concerning prisoners' clothing but these were rejected by the inmates. When the taproom was closed, prisoners simply purchased beer from passers-by on the street through the grates.

The tradition of prisoner self-management clearly led to a strong culture of prisoner initiative and collaboration. Prisoners knew how to elicit sympathy from those who visited the prison, extracting food, money, and drink from visitors. They also collaborated in developing methods of obtaining the most favourable sentences and verdicts when they appeared in court. From the 1780s, those convicted of forgery helped each other write petitions to the Bank of England soliciting financial support, a plea bargain, or a reduction of their sentence, many of which were successful.17 In 1789, groups of prisoners anxious about the prospect of transportation to Australia conspired together in agreeing to refuse the royal pardon. In addition, the open nature of the prison allowed radical prisoners, such as John Wilkes, to coordinate their political campaigns from inside the prison. In the 1790s, partly stimulated by the presence of Lord George Gordon, a heterodox republican and Jacobin culture developed in the prison, which formed networks and even published radical literature.18

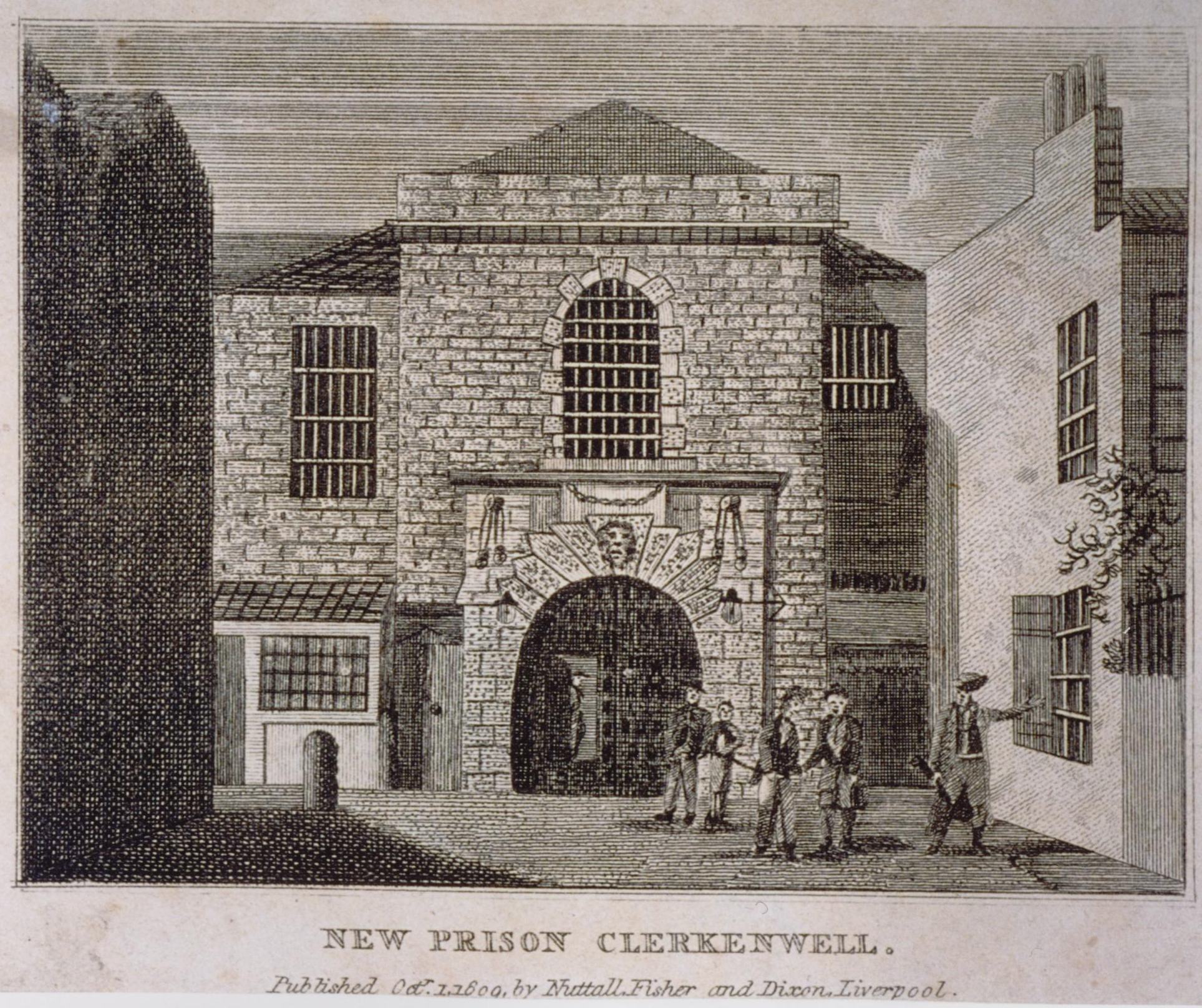

New Prison, Clerkenwell 1809. Reproduced from Mark Herber. Criminal London: A Pictorial History from Medieval Times to 1939. Chichester 2002, p.166. ©Mark Herber.

New Prison, Clerkenwell 1809. Reproduced from Mark Herber. Criminal London: A Pictorial History from Medieval Times to 1939. Chichester 2002, p.166. ©Mark Herber.

New Prison

Located in Clerkenwell, New Prison held those accused of petty and serious crimes in Middlesex while they awaited trial. Owing to overcrowding at Newgate, those who were to be tried at the Old Bailey were not transferred to Newgate until just before the start of the sessions. The original prison was extended in 1773-75 in order to accommodate more felons, but there were nonetheless escape attempts in the 1780s.

Poultry Compter

This was a sheriff's prison in the City, used primarily for prisoners committed by the Lord Mayor. Although primarily used for debtors, it also held those arrested by the night watch and accused criminals awaiting trial. The prisoners were not segregated and conditions were described as poor. In 1776 William Smith described this prison as a place where "riot, drunkenness, blasphemy and debauchery, echo from the walls, sickness and misery are confined within them".19 In 1791 it was replaced by the Giltspur Street Compter.

Savoy

Built in 1695 as a military prison, the Savoy held deserters and military offenders.

Surrey Gaol

This prison held those accused of crimes and awaiting their trials from Surrey, as well as convicts awaiting transportation. In 1770 it was the subject of a grand jury presentment which described it as "too small, unhealthy, inconvenient and unsafe".20 Although enlarged in 1771, it was replaced with the Horsemonger Lane Gaol in 1791.

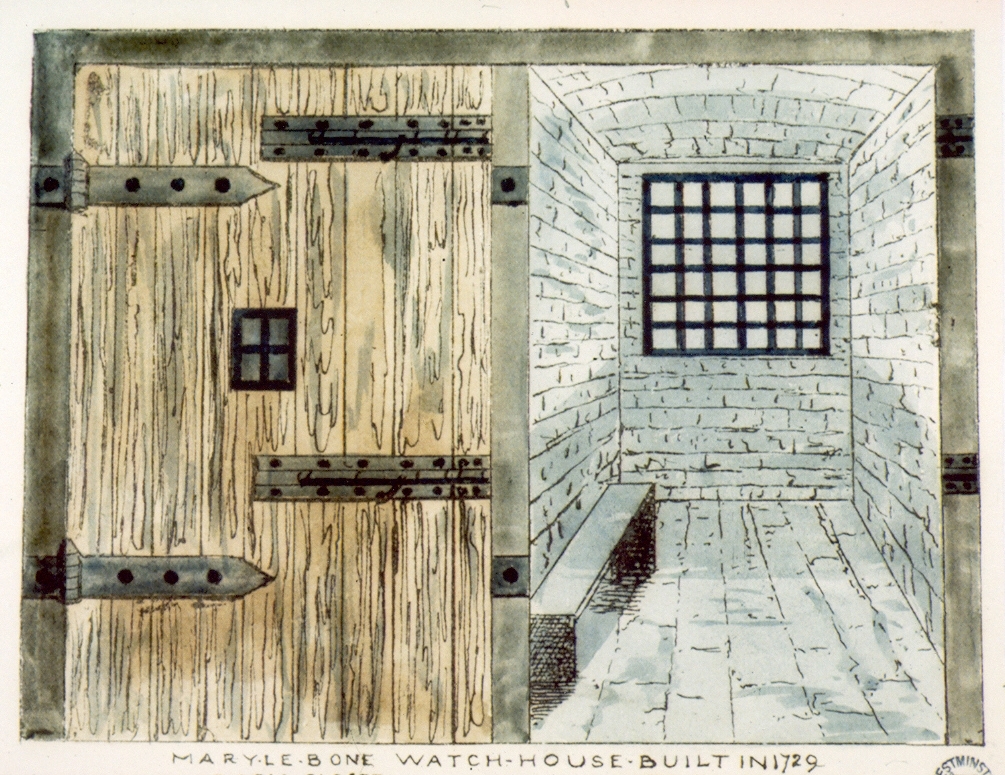

Watchhouses

Every parish had a watchhouse, where those apprehended by the night watch could be kept overnight before they were examined by a Justice of the Peace in the morning. While facilities varied, watchhouses typically had a public room, where the keeper profited from the sale of drinks, and holding cells. The watchhouse was known by the poor as a place where emergency relief could be obtained, but conditions in the cells could be horrific, particularly when overcrowded.21 In 1742 four women suffocated to death in the St Martin's Roundhouse and the keeper, William Bird, was put on trial for murder at the Old Bailey.

St Marylebone Watchhouse Cell. © Westminster Archives Centre.

St Marylebone Watchhouse Cell. © Westminster Archives Centre.

Wellclose Square

This small prison, essentially just an ordinary house, served the Tower Liberty. In 1792 it was described as being in "ruinous" condition.

Whitechapel Debtors' Prison

This prison held debtors sentenced by courts serving the manors of Stepney and Hackney. An attempt by the constables and other officers of the Tower Hamlets to obtain permission to use it also for petty criminal offenders, to save them the trouble of carrying prisoners all the way to the Middlesex house of correction or New Prison in Clerkenwell, was rejected by the Middlesex Justices in 1707, but it is possible that in spite of this ruling such prisoners were held here.

Wood Street Compter

Like the Poultry Compter, the Wood Street Compter was a sheriff's prison. Primarily used for debtors, it also held those arrested by the night watch and accused criminals awaiting trial. Prisoners were segregated according to their wealth, and tradesmen debtors were able to continue practising their trades. Poor prisoners could beg for cash or food from passers-by. The male and female felons were each confined to two rooms. This was clearly an unreformed prison: in 1776 William Smith described the prison as "dark, confined, ill-aired, and full of filth and vermin. There are no proper divisions for men and women, debtors and felons".22 It burned down in 1780 and was rebuilt, only to be closed in 1797, when the prisoners were moved to the Giltspur Street Compter.

Introductory Reading

- Brown, Roger Lee. A History of the Fleet Prison, London: The Anatomy of the Fleet. Studies in British History, 42. Lampeter, 1996.

- Byrne, Richard. Prisons and Punishments of London. 1929.

- Chalklin, C. W., The Reconstruction of London's Prisons 1770-99: An Aspect of the Growth of Georgian London. London Journal 9 (1983), pp. 21-34.

- Evans, R. The Fabrication of Virtue: Prison Architecture, 1750-1840. Cambridge, 1982.

- Sheehan, W. H. Finding Solace in Eighteenth-Century Newgate. In Cockburn, J. S., ed., Crime in England 1550-1800. 1977, pp. 229-45.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 Daniel Defoe, A Tour thro' the Whole Island of Great Britain [1724], p. 155. ⇑

2 11 William III c. 19. ⇑

3 14 George III c. 59. ⇑

4 19 George III c. 74. ⇑

5 24 George III c. 54. ⇑

6 Simon Devereaux, The Making of the Penitentiary Act, 1775-1779, Historical Journal, 42 (1999), p. 416. ⇑

7 S. E. Brown, Policing and Privilege: The Resistance to Penal Reform in Eighteenth-Century London, in Anne Goldgar and Robert Frost, eds, Institutional Culture in Early Modern Society, Cultures, Beliefs, and Traditions, 20 (Leiden and Boston, Mass., 2004). ⇑

8 Joseph Crook and Michael Port, The History of the King's Works, Vol. 6: 1782-1851 (1973), p. 628. ⇑

9 Ruth Paley, Thief-Takers in London in the Age of the McDaniel Gang, c. 1745-1754, in D. Hay and F. Snyder, eds, Policing and Prosecution in Britain 1750-1850 (Oxford, 1989), p. 326. ⇑

10 Richard Byrne, Prisons and Punishments of London (1929), pp. 47-50. ⇑

11 Bruce Watson, The Compter Prisons of London, London Archaeologist, 7 (1993), p. 120. ⇑

12 16 George III c. 43. ⇑

13 Charles Campbell, The Intolerable Hulks (Bowie, 1993), pp. 34-35. ⇑

14 Cited in Crook and Port, The History of the King's Works, p. 628. ⇑

15 Batty Langley, An Accurate Description of Newgate (1724), p. 35. ⇑

16 Arthur Griffiths, The Chronicles of Newgate, 2 vols (1884), p. 388. ⇑

17 Deirdre Palk, (ed.), Prisoners' Letters to the Bank of England, 1781-1827 (London Record Society vol. 42, 2007). ⇑

18 Iain McCalman, Newgate in Revolution: Radical Enthusiasm and Romantic Counterculture, Eighteenth Century Life, 22:1 (1998), pp. 95-110. ⇑

19 William Smith, State of the Gaols in London, Westminster, and the Borough of Southwark (1776), p. 33. ⇑

20 Cited by C. W. Chalklin, The Reconstruction of London's Prisons 1770-99: An Aspect of the Growth of Georgian London, London Journal 9 (1983), p. 27. ⇑

21 Tim Hitchcock, Down and Out in Eighteenth-Century London (London, 2004), p. 153. ⇑

22 Smith, State of the Gaols, p. 31. ⇑