Westminster

Caleb Robert Stanley, The Strand, Looking Eastwards from Exeter Change, c.1824. ©Museum of London.

Caleb Robert Stanley, The Strand, Looking Eastwards from Exeter Change, c.1824. ©Museum of London.

Introduction

The settlement which grew up around Westminster Abbey, the royal palace, and Parliament which came to be known as Westminster was part of the County of Middlesex and separate from the City of London. Following the dissolution of the monastaries, Westminster Abbey no longer dominated the city, and in 1585 a Court of Burgesses was established with the power to regulate nuisances and adjudicate prosecutions for minor criminal offences. In 1618, a commission of the peace was established, entitling its Justices of the Peace to hold a separate sessions. Attempts to incorporate the growing city failed three times in the late sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries. Westminster remained a city without a charter owing to the dominant presence of the royal court and the Abbey, which did not wish to see any rivals to their influence; competition between the Court of Burgesses and the sessions; and the superior status of the Middlesex sessions. City-wide institutions remained weak, allowing the individual parishes to become powerful.

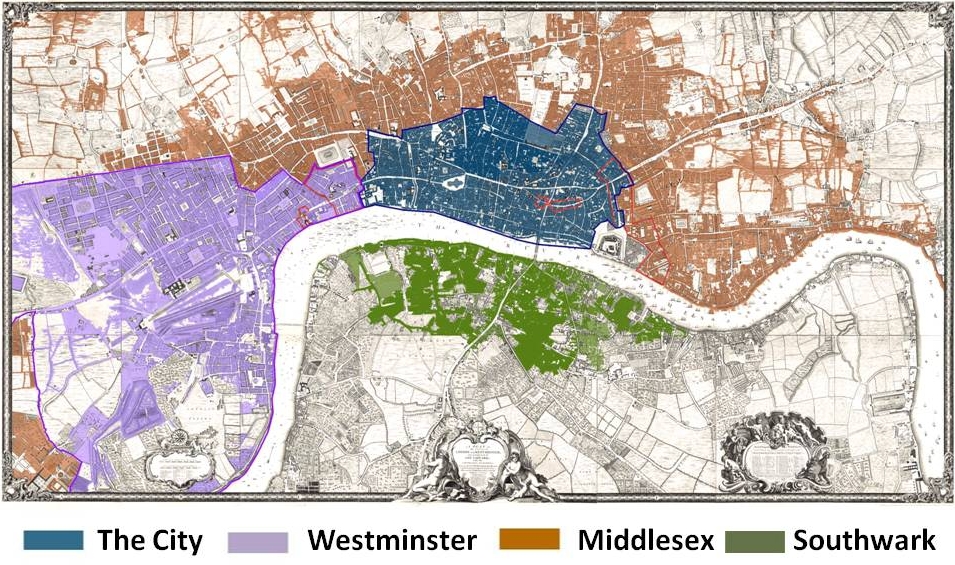

The City of London is indicated in dark blue, Westminster in purple, Middlesex in brown, and Southwark in green. The base map is John Rocque's, London, Westminster and Southwark, 1746. © Motco 2001 (base map only).

The City of London is indicated in dark blue, Westminster in purple, Middlesex in brown, and Southwark in green. The base map is John Rocque's, London, Westminster and Southwark, 1746. © Motco 2001 (base map only).

In 1700, Westminster contained around 130,000 inhabitants, and was larger than any other city in the country, except the rest of London; by 1801 it had grown to 165,000. Westminster contained extremes of wealth and poverty, as the gentry and aristocracy attached to parliament and the court lived alongside the servants, craftsmen and tradesmen who catered for their needs. Almost half of the households in St Margaret and a fifth of the households in St Martin were exempt from paying the hearth tax in 1664, while 34 per cent and 42 per cent respectively of their households contained five or more hearths.1 While the newer, western parts of the city were dominated by fashionable squares inhabited by elites, some of the older parts of the city on its eastern boundary (with the City of London) were starting to be considered slums. Conflicts between Westminster's richer and poorer inhabitants account for the fact the city's parishes had some of the highest prosecution rates for petty crime in the metropolis in the early eighteenth century, when the city was the focus of the activities of the Societies for the Reformation of Manners to eliminate vice, but these efforts generated considerable opposition from local inhabitants.

London Lives includes a full set of records of one parish, St Clement Danes, and settlement examinations and workhouse registers from St Martin in the Fields.

Court of Burgesses

Established in 1585 to address the growing problems of immigration, poverty and immorality in Westminster, the Court of Burgesses, chaired by the Dean or High Steward of Westminster Abbey, was essentially a manorial court, but unlike a manorial court it met weekly. The court was responsible for the appointment of constables and the regulation of the night watch. The parishes were divided into a total of twelve wards, each of which had a burgess and deputy burgess, appointed by the High Steward. Each ward had a beadle who was expected to report lodgers and new immigrants, drive out vagrants and beggars, go through the streets four times a day to prevent "disorders" and supervise the watch. A leet jury was responsible for reporting nuisances to the court periodically. The fact that the court's powers overlapped with those of the parishes and Justices meant that conflicts were inevitable between the different jurisdictions, and the burgesses were the ones who ultimately lost out.

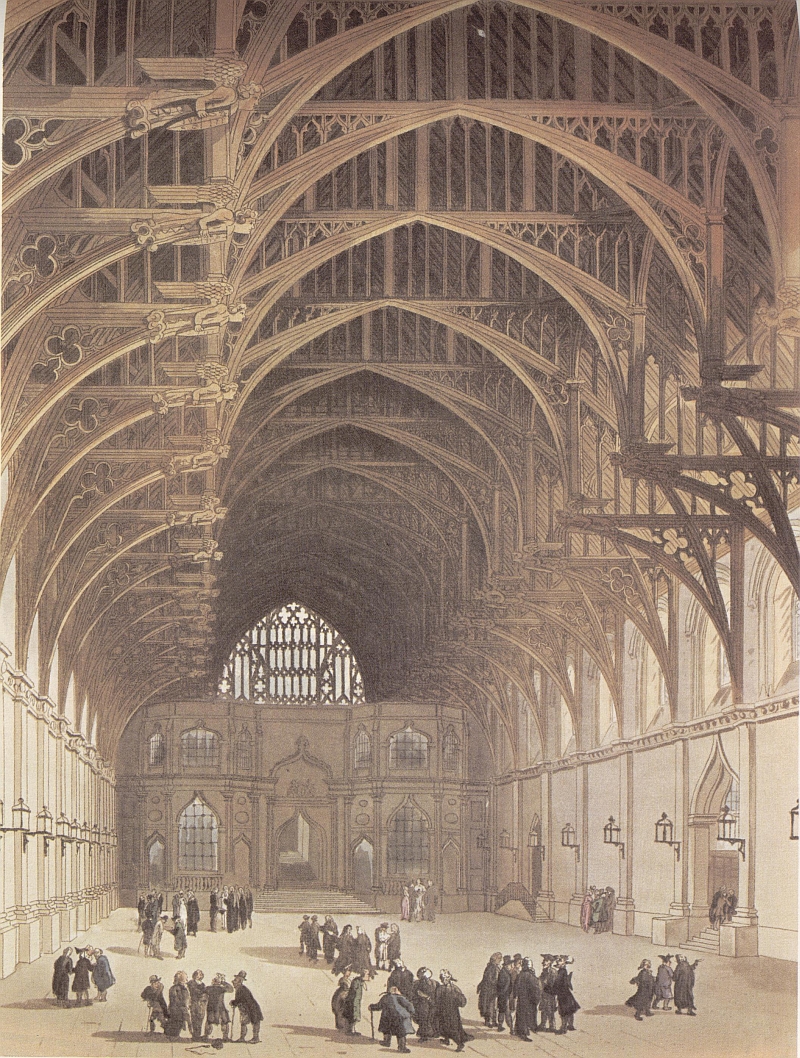

Westminster Hall, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Westminster Hall, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

In the early eighteenth century the court's activities were largely confined to the punishment of nuisance and regulatory offences, with a trickle of prosecutions for disorderly houses, gaming houses and brothels. In 1707 the court heard sixty-eight cases of failure to repair the streets, fifty-six cases of selling in false measures, and twenty-five other regulatory cases, as well as seventeen cases of disorderly, bawdy or gaming houses. There were frequent conflicts with the Westminster Justices and parish vestries over issues such as the appointment of watchmen and constables, and in 1722 the the burgesses were blamed for undermining the Justices' campaign to suppress gaming houses (allegedly because the burgesses derived income from the fines they imposed on such houses). In the 1730s the court lost its struggle with the parish vestries for control of the night watch.

By the middle of the eighteenth century, the court had lost most of its powers, and was, in the words of Sydney and Beatrice Webb, "flattened into a mere formality".2 It was not abolished, however, until 1900. The records of the Court of Burgesses are kept at the Westminster Archives Centre.

Sessions

By virtue of their commission of the peace, the Westminster Justices of the Peace had the power to hold sessions four times a year for the purpose of trying misdemeanor offences arising within the city. But because jurisdiction of the Middlesex commission of the peace also included Westminster, and its sessions met more often, eight times a year, many Westminster cases were heard at the Middlesex sessions. Nonetheless, the Westminster sessions dealt with the full range of business conducted by the Justices at the Middlesex sessions, as documented in its Sessions Papers (PS). Most Westminster Justices, including Henry Fielding, also sat on the commission of the peace for Middlesex.

The increasing power of the Middlesex sessions, however, meant that by the 1750s the Westminster Justices had lost most of their power and prestige, and residents of Westminster increasingly chose to have their cases tried in Middlesex. This was exacerbated by the rivalry which developed in the years 1765-1780 between the chairs of the two benches of Justices, John Fielding in Westminster and John Hawkins in Middlesex.

Individual Justices of the Peace, however, could still be powerful and introduce innovative practices, when they had the support of the government, such as the court justices who received payments from the Treasury for their services. Around 1730 Thomas De Veil set up an office in Leicester Square where he could hear criminal complaints and examine suspects, and in 1740 he moved the office to Bow Street. Following his death, the Bow Street office was taken over by Henry and later John Fielding, and was the site where they introduced the Bow Street Runners and developed the practice of holding pre-trial hearings before suspects were committed for trial at the Old Bailey.

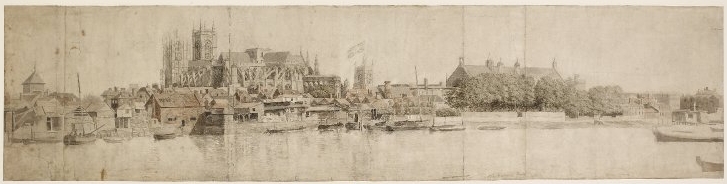

Samuel Scott. Westminster Abbey and Hall. 1739. British Museum, Binyon 3. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Samuel Scott. Westminster Abbey and Hall. 1739. British Museum, Binyon 3. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Parishes

Westminster was comprised of nine parishes:

- St Anne

- St Clement Danes

- St George, Hanover Square (formed from St Martin's in 1724)

- St James

- St John (formed from St Margaret in 1728, but the two parishes remained united for the purposes of poor relief and local government)

- St Margaret

- St Martin in the Fields

- St Mary-le-Strand

- St Paul Covent Garden

By the eighteenth century, some of these had grown to a substantial size. In the 1720s St Martin had over 22,000 inhabitants, St Margaret over 17,000, and St James over 16,000. Unlike the City of London, where the responsibility for local government was split between the parishes and the wards, and with the Court of Burgesses and sessions relatively weak, Westminster parishes possessed considerable powers of self government. Dating from the sixteenth century, they began to form select vestries, which replaced open meetings of rate payers as the parishes' decision-making bodies, in order to cope with the increasing volume of parochial business. Over time these vestries evolved into powerful groups of officeholders, who selected their own members. Membership typically included not only senior parish officers such as the churchwarden and overseer of the poor, but also, in the wealthier parishes, prominent gentry and noblemen who lived in the parish, including Justices of the Peace and members of parliament. Both the prime minister, Sir Robert Walpole, and his younger brother Horatio were elected to the vestry of St Margaret's Westminster in July 1729.3 By the 1720s all nine parishes in Westminster had select vestries.

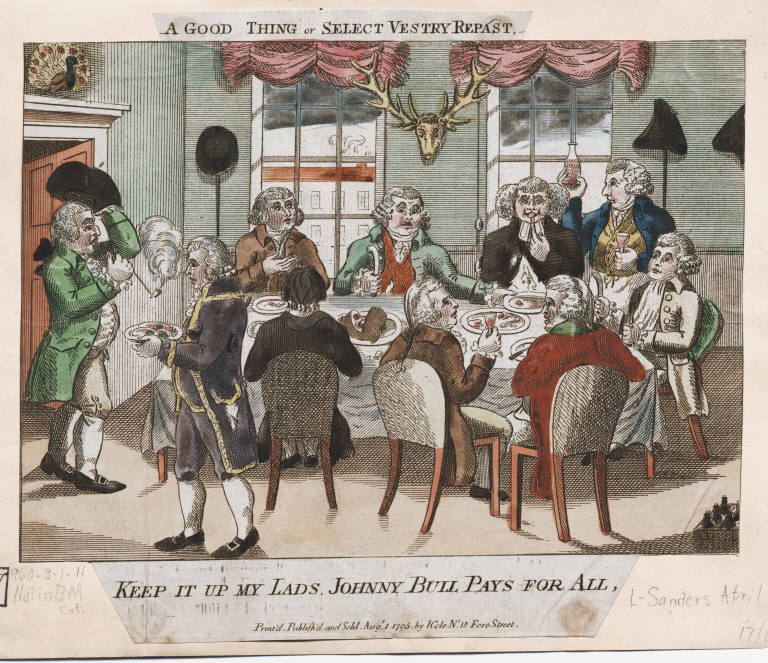

A Good Thing, or Select Vestry Repast, 1795, Lewis Walpole Library, 795.8.1.1 ©Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

A Good Thing, or Select Vestry Repast, 1795, Lewis Walpole Library, 795.8.1.1 ©Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Often termed closed, these select vestries were frequently accused of corruption, and of exercising powers they did not possess. In St Martin's the vestry merged almost imperceptibly with a petty sessions of Justices of the Peace, allowing members who were not actually Justices to adopt some judicial powers, including appointing constables and other officers, issuing orders concerning poor relief, and levying rates. The fact such vestries often acted in secret, and refused to divulge their records, is indicative of their oligarchic approach to government. They controlled parochial finances, the administration of poor relief, the appointment of parochial officers, and even voting lists for members of parliament. Using the political clout of their aristocratic members, many managed to increase their powers by recourse to Parliament, obtaining local acts which gave them the authority to tax inhabitants in order to carry out improvements, such as to the night watch and the paving, cleaning and lighting of the streets, and to build workhouses. Although each parish adopted its own approach, the vestries responded to similar social problems within similar constraints, and broad similarities in their policies can be detected. As is evident in the 1774 Westminster Night Watch Act, they were even willing to accept some overarching regulation of their activities.

Whether these vestries were as corrupt as was often alleged is a matter of dispute, but it is undoubtedly the case that they introduced numerous innovations to the administration of local government, many of which were needed in the context of increasing populations and the growth of social problems in their parishes. This was not the only part of the metropolis where closed parish vestries were to be found, but owing to weak central government in Westminster this was where they became most powerful.

Liberties

Five relatively small parts of Westminster fell outside the jurisdiction of the parishes and, owing to historic rights and privileges, were governed separately. Westminster Abbey was governed by the Dean and Chapter of the Abbey. The palaces of St James and Whitehall and the Privy Gardens were under the jurisdiction of the crown and the Palace Court of Westminster. The Precinct of the Savoy, located between the Strand and the Thames between the two separated parts of the parish of St Clement Danes, was formerly the palace of the Duke of Lancaster and was now a liberty of the crown and governed by a manorial court leet. The Liberty of the Rolls, on the eastern boundary of Westminster next to the City of London, was self governing. The existence of these anomalous jurisdictions made it even less likely that a uniform city-wide government could be created in Westminster.

Elections

In the pre-reformed electoral system the Westminster parliamentary constituency elected two MPs. It had the biggest and one of the most socially mixed urban electorates in the country, with some 12,000 voters in 1754, facilitating a new type of politics. Unlike most constituencies, where voting was restricted to those with substantial property, the franchise was extended to all "scot and lot" tax payers: all householders who contributed financially to the parish, typically by paying the poor rates. (Also eligible to vote were householders in privileged parts of the city where no poor rates were payable, including the Inns in Chancery, Whitehall, and the royal palaces.) While this made for an unusually democratic electorate, women were not eligible to vote.4

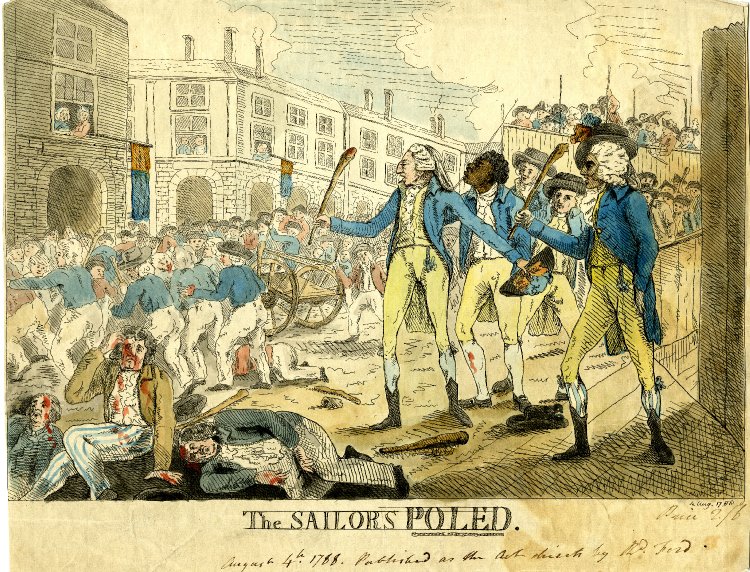

An Election Riot in Covent Garden, 4 August 1788. British Museum, Satires 7367. © Trustees of the British Museum.

An Election Riot in Covent Garden, 4 August 1788. British Museum, Satires 7367. © Trustees of the British Museum.

With such a large electorate, traditional means of canvassing votes, by cultivating ties of patronage and deference and "treating" (bribing) the voters with elaborate hospitality, had only limited success. It is true that the influence of magistrates, the elite-dominated parish vestries, the royal household, government offices, and the Deanery of Westminster secured many votes for the government. Moreover, ties of aristocratic patronage did determine the votes of many tradesmen and craftsmen who worked directly for the nobility. Nonetheless, there were large numbers of independent voters who were not affected by, or who actively resisted, such ties. Whereas in the vast majority of eighteenth-century English elections contests were either avoided, by the practice of elites selecting successful candidates in advance, or fought on local issues, Westminster elections were routinely contested, often bitterly, on national political issues, and at great expense.5

Westminster politics was unusually open, both to violence, as hired mobs tried to coerce voters, and to the claims of political parties and ideologies. Some of the country's first extra-parliamentary political organisations were formed, notably the Independent Electors of Westminster in the late 1730s, which helped opposition candidates win the 1741 election, and the Whig Club, founded in 1784 to organise support for the prominent Whig politician Charles James Fox. At times, Westminster became a hotbed of anti-government and radical politics, such as during the 1749 by-election when Sir George Vandeput, sponsored by the Independent Electors, contested the seat held by the court candidate Lord Trentham. Trentham was ruthlessly criticised for his support of government attacks on popular liberties, evident in the execution a few weeks previously of the journeyman Bosavern Penlez for his alleged participation in a riotous attack on a brothel. Despite widespread disorder, Trentham won narrowly.6

Thomas Rowlandson, The Hustings Outside St Paul's Covent Garden at an Election, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Thomas Rowlandson, The Hustings Outside St Paul's Covent Garden at an Election, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

Elections in Westminster during the 1770s, 1780s and 1790s were hotly contested on national issues including parliamentary reform, the American War, and the French Revolution. In 1770 the Wilkite radical Sir Robert Bernard was elected unopposed; he was the first opponent to the government elected since 1741. Fox was elected in 1780 and 1784, before the growing cost of elections forced the government and the opposition to agree in 1790 to nominate one candidate each and avoid a contest. Rejecting this attempt to prevent a vote, Horne Tooke stood as a radical candidate in 1790 and 1796 but lost both times.7 Despite its democratic credentials and radical politics, election results in Westminster did not often go against the government.

Until the introduction of the secret ballot in 1872, all votes were publicly recorded in poll books, which recorded the voter's name (and often occupation) and the candidates he voted for, thereby greasing the wheels of patron-client relationships. These poll books have been included on this London Lives website, along with rate books which list the names, addresses, and property values of all householders taxed by parishes to meet the costs of poor relief, the night watch, and lighting, cleaning and repairing the streets. By searching names across these two databases, as well as all the other resources provided on this website, it is possible to discover considerable information about Westminster's voters.

Introductory Reading

- Harvey, Charles, Green, Edmund and Corfield, Penelope. The Westminster Historical Database: Voters, Social Structure and Electoral Behaviour. Bristol, 1998.

- Merritt, J. F. The Social World of Early Modern Westminster: Abbey, Court and Community, 1525-1640. Manchester, 2005.

- Reynolds, Elaine. Before the Bobbies: The Night Watch and Police Reform in Metropolitan London, 1720-1830. London, 1998.

- Rogers, Nicholas. Aristocratic Clientage, Trade and Dependency: Popular Politics in Pre-Radical Westminster, Past and Present 61 (1973), pp. 70-106.

- Shoemaker, Robert B. Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex. Cambridge, 1991, chap. 10.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 Robert B. Shoemaker, Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex (Cambridge, 1991), p. 291. ⇑

2 Sydney and Beatrice Webb, English Local Government from the Revolution to the Municipal Corporations Act: Vol. 2, The Manor and the Borough (London, 1908), p. 95. ⇑

3 Westminster Archives Centre, St Margaret Westminster, Vestry Minutes and Orders, 1724-1738, Ms E2419 shelf 38, p. 208. ⇑

4 Charles Harvey, Edmund Green, and Penelope Corfield, The Westminster Historical Database: Voters, Social Structure and Electoral Behaviour (Bristol, 1998), pp. 2-3, 15. ⇑

5 Nicholas Rogers, Aristocratic Clientage, Trade and Dependency: Popular Politics in Pre-Radical Westminster, Past and Present 61 (1973), pp. 70-106. ⇑

6 Nicholas Rogers, Whigs and Cities: Popular Politics in the Age of Walpole and Pitt (Oxford, 1989), pp. 168-76. ⇑

7 Harvey, Green, and Corfield, Westminster Historical Database, pp. 40-41. ⇑