Carpenters' Company

Eighteenth-century woodworking tools. © The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Eighteenth-century woodworking tools. © The Colonial Williamsburg Foundation.

Introduction

Carpentry was central to the building and rebuilding of eighteenth-century London that allowed its population to grow. The requirement that houses be built out of brick following the Great Fire of 1666 reduced demand and changed the character of the trade, but carpentry remained a central part of the building process. Its practitioners spanned the social scale from wealthy building contractors to day labourers. Like all other guilds, the ability of the Carpenters' Company to regulate the trade declined considerably during the century. Nonetheless, membership remained attractive, not least because the Company continued to play a significant role in the distribution of charity, from which many of its members benefited.

The Carpenters' Company was selected as a representative guild for inclusion in London Lives because it remained active in the eighteenth century, its records are reasonably complete, and its members included a number of poorer men of the sort who are likely to turn up in other records included in this resource.

Carpentry as a Trade

While carpenters prospered in the seventeenth century, especially during the building boom following the Great Fire, once rebuilding was completed the trade declined somewhat. New requirements that houses be constructed out of brick and stone did not eliminate the use of timber for structural components, but this work was utilitarian and hidden, and tended to command less respect as a result.

In 1747 R. Campbell described the work of a house carpenter as follows:

In contrast, a joiner:

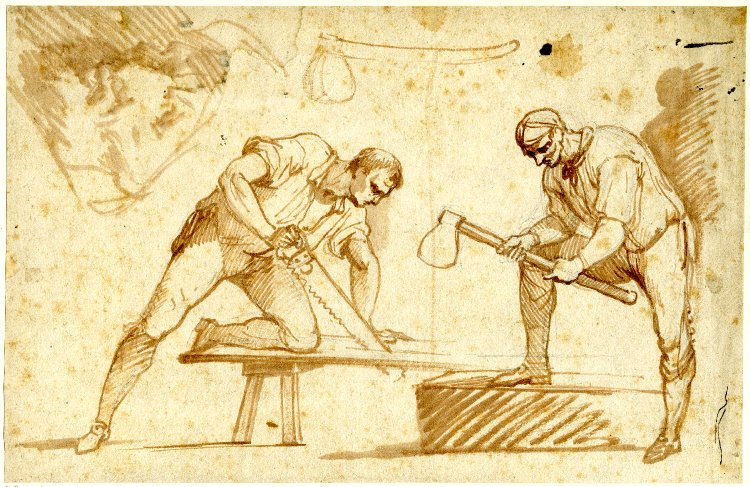

John Hamilton Mortimer. Studies of Carpenters. 1770-1771. British Museum, Binyon 10(b), Sunderland 41(2a). © Trustees of the British Museum.

John Hamilton Mortimer. Studies of Carpenters. 1770-1771. British Museum, Binyon 10(b), Sunderland 41(2a). © Trustees of the British Museum.

Although the same person often performed both trades, the tasks were distinct, and carpentry was the lesser skilled of the two.

There were three distinct categories of carpenter: master carpenters; small master craftsmen and their apprentices; and journeymen and labourers. Master carpenters were effectively building contractors, responsible for not just the construction but sometimes also the design of buildings and supply of building materials. Some master carpenters managed to accumulate considerable wealth. In some cases, they owned the houses they built and let them out as tenements.

The lowest end of the trade was the largest, partly because, as explained under company powers, the Company lost its ability to restrict entry into the trade. Wage rates were those typical of skilled, but not highly skilled, craftsmen. Because the vast majority of carpenters were journeymen and labourers, the overall reputation of the trade was relatively low. The work was physically demanding, and carpenters were among the "inferior trades" accused of being involved in the gin trade.

Company Membership

Despite the Company’s limited powers, many master carpenters continued to become free of the Company in the eighteenth century, and most members continued to practise the trade. Members benefited from the prestige of membership and from Company charity when they fell on hard times, and because membership offered voting rights in the City and the possibility of obtaining City offices, as well as useful business contacts. Around 1700 the Company admitted sixty freemen a year, and in 1763 there were so many admissions that a thousand copies of the oaths taken when freemen were admitted were printed.2 For records of the admission of freemen, see the Court of Assistants Minute Books (MC).

In addition to the completion of an apprenticeship with the Company, as in other guilds membership could be acquired by patrimony (if one's father had been a member) or by redemption (payment of a fee). Together with the right possessed by freemen of London to practise any trade in the City (owing to the Custom of London), membership by patrimony or redemption offered the possibility that members of the Company were not actually carpenters, but the Company repeatedly tried to ensure its members did practise the trade, with some success. For most of the eighteenth century the majority of members were either carpenters or members of related building trades. Of the hundred liverymen in 1746, seventy were carpenters and thirteen were timber merchants, with the remainder in a wide variety of other trades, including three "gentlemen". By 1823, however, only twenty of liverymen were carpenters.3

A delftware mug, displaying the arms of the Carpenters' Company. 1724. British Museum, Hobson 1903 E109 (Plate 13), Lipski & Archer 1984 p.180, fig.808, Tilley 1968a pp.126-7 & fig.3 © Trustees of the British Musuem

A delftware mug, displaying the arms of the Carpenters' Company. 1724. British Museum, Hobson 1903 E109 (Plate 13), Lipski & Archer 1984 p.180, fig.808, Tilley 1968a pp.126-7 & fig.3 © Trustees of the British Musuem

Reflecting the relatively low status of carpentry, most members were men of modest wealth, from humble backgrounds. None were women, though a very small number of women practised the trade outside the Company. Of the carpenters listed in insurance registers, just 0.6 per cent were women.4

One member who has recently attracted historical attention is William Payne, who was apprenticed to a master carpenter in the 1720s, became a journeyman around 1740, and purchased membership in the Company in 1755. Calling himself "the little English Carpenter", he continued working in the trade until the 1770s, shortly before his death in 1782. Yet Payne appears to have spent a large part of his time away from his trade, acting as a zealous parish officer and informer prosecuting a wide range of criminal and immoral activity.5

Apprentices

Despite the Company's increasingly limited powers, significant numbers of young men (and a few women) continued to enter into apprenticeship indentures, with the numbers fluctuating from year to year, as can be seen from the following samples from the Company's registers:

- 1685-94: 54 apprentices per year6

- 1700-10: 100 apprentices per year

- 1740-50 52 apprentices per year7

By the late eighteenth century, however, numbers had apparently declined significantly.

Around half of the apprentices came from London and the others from the rest of the country. The latter often returned home after their training, which is one reason why the number of those who took up the freedom of the Company upon completion of their apprenticeships was considerably lower than the number of registered apprentices.

The social backgrounds of apprentices to the Carpenters' Company were mixed, but primarily they came from urban trade and craft backgrounds. Fathers' occupations for the 230 apprentices enrolled between 1690 and 1693 were:

- 5% gentlemen

- 11% yeomen

- 8% husbandmen

- 2% professional

- 57% merchants, tradesmen and craftsmen

- 17% citizens of London8

A few girls became apprentices, particularly early in the century. See, for example, the apprentices bound to Katherine Eyre between 1701 and 1707, which can be found by searching for her name in the Court of Assistants Minute Books (MC).

The apprenticeship indentures and registers are not included on this website. However, numerous records of the binding of apprentices, transfers of masters when a master died or the indenture was dissolved, and of apprentices becoming freemen can be found in the Court of Assistants Minute Books (MC). For more information about researching apprentices, see the Research Guide.

The Decline of Company Powers

Like most guilds, the Company's charter gave it the power to regulate entry to the trade and to enforce standards of craftsmanship. Its jurisdiction covered the City of London and areas within twelve miles of the City. Those who practised carpentry were required to have served an apprenticeship in the trade and to be members of the Company. However, owing to the Custom of London, members of companies in the City could practise any trade in London, including carpentry, so not all practising carpenters were actually members of the Company, and vice versa.

According to its charter, Company officers could enter the premises of any member of the Company, or of anyone else practising carpentry, in order to ensure that the standards of the trade were met. They could seize and destroy any improperly made goods and punish the offenders. Needless to say, these inspections were often opposed, both by physical resistance and with lawsuits.

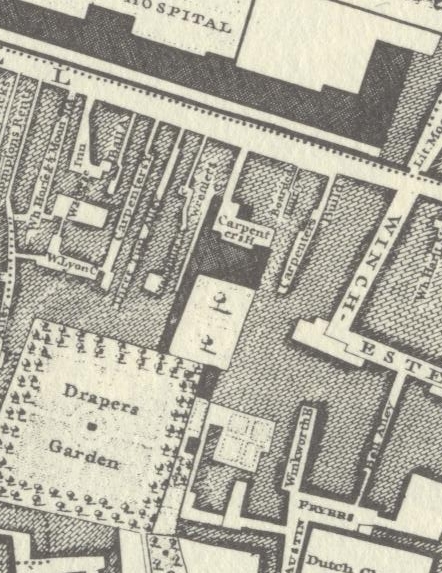

Detail, John Rocque. Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster and Borough of Southwark. 1747. © London Lives.

Detail, John Rocque. Plan of the Cities of London and Westminster and Borough of Southwark. 1747. © London Lives.

From the late seventeenth century, however, the powers of the London guilds declined. This was exacerbated in the case of the building trades by the Great Fire, which relaxed guild powers (in theory, for only seven years), allowing non-members who had served apprenticeships elsewhere in the country to practise in London. Immigrant carpenters, who came from all over England, did not respect traditional distinctions between joinery and carpentry, making these distinctions difficult to enforce.

Attempts to enforce the Company's jurisdiction over carpentry, by forcing those practising the trade either to desist or become members, were increasingly unsuccessful. Guild powers were undermined by successful challenges in the common law courts, and increasingly the Company chose to defer enforcement of its powers to City officials. In 1739 the Company ruled that any complaints about carpenters who were not free of the Company should be referred to the City Chamberlain because investigating the complaints took too much time. As historians of the Company comment, this decision "seems to mark the end of the Company’s long and fruitless attempts to control the trade of carpentry in London".9 Unsurprisingly, Company membership declined in the first half of the eighteenth century. Perhaps as a consequence, the Company ceased to enforce its apprenticeship rules, allowing masters to have as many apprentices as they wished.

The Company also became increasingly unable to enforce its powers of inspection. Following the Great Fire, the City temporarily took over the enforcement of building standards and it proved difficult to re-establish those powers, in part owing to legal challenges. Some City companies secured new powers to reinforce their rights, but the Carpenters did not choose to do this. As a consequence, the inspection of buildings almost ceased in the eighteenth century, and there are very few instances in which poorly made goods were seized and destroyed.

By the end of the eighteenth century, therefore, the business of the Company was almost exclusively confined to registering apprentices, admitting freemen, managing its properties and funds, and dispensing hospitality and charity.

Labour Disputes

By mid century, the Company was no longer able to protect the interests of carpenters who were wage labourers. Instead, workers in the trade formed clubs and societies in order to defend the practice of taking wood scraps as "perquisites" and to push for higher wages. During the second half of the century they were involved in a number of labour disputes and strikes. Most notably, in 1776 3,000 carpenters in Holborn, Westminster and Southwark demanded an extra two shillings a week and began to pull down scaffolding around new buildings in St Giles, and in 1787 there was a strike of 4,000 London carpenters and joiners seeking a wage increase (despite the arrest of their leaders the strike was successful).10 As an institution which was unable effectively to represent the interests of either the workers or their employers, the Carpenters' Company did not play a significant role in these disputes.

Charity

Like all guilds, the Carpenters' Company had a tradition of looking after its poorer members and their dependents. Using money donated both from bequests and its own funds, the Company was a source of substantial relief for members who fell on hard times, retired members, and their widows. Reflecting a decline in the practice of leaving bequests and changing priorities, however, the amount of money spent on charity declined in the second half of the eighteenth century.

The Company administered several bequests left by its members. One of the biggest was left by Richard Wyatt in 1618, which included payments of ten shillings annually for thirteen poor widows of the Company. Later bequests included:

- 1680 William Pope left property, the rental income from which was to be distributed to seven poor members or their widows.

- 1736 Mr Burgin gave £100, the interest to be divided annually among the sixteen poor freemen of the Company who were next in turn to receive a pension.

- 1753 Mr Langton gave £50, the interest to be annually divided amongst the poor of the Company.

- 1764-66 Mr Robinson gave £300, the interest to be expended for the benefit of the poor of the Company.

- 1775 Mr Reynolds gave £300, the interest to be divided annually amongst nine poor freemen of the Company, initially at twenty shillings per year.11

Members also left money for the Company to administer on behalf of the poor more generally. Included in Richard Wyatt's will was a group of almshouses in Godalming, Surrey, for ten poor men from specified parishes outside London, and in 1718 Sir John Cass left money for twenty almshouses in Portsoken Ward for the poor, but his will was disputed and the houses were never built. Administering (and litigating over) bequests like this took a considerable amount of time and resources, and included the funding of lavish hospitality on occasions such as the annual officers' visit to Godalming to inspect Wyatt's almshouses.

In addition, the Company also funded pensions. In the late seventeenth century it provided pensions for sixty members or their widows, and this number was increased to 100 in 1710. The amount was gradually raised over time, from four shillings a quarter in the late seventeenth century to eight in 1734-35, and ten in 1738. In 1747 a new class of pensioners was created, the widows of liverymen, who received twenty-six shillings per quarter.

Other poor members received regular gifts from the Company. In the late seventeenth century, when there were sixty pensioners, there were "as many more which they are forced to relieve yearly, as accidental poor".12 In the 1730s the Company voted to distribute £40 or £50 each quarter to the poor. Special gifts were distributed on St James's Day (July 25th); in 1730, fifty members received twelve shillings, to be distributed every other year. In 1743 ten shillings was given to 100 people each quarter, in addition to a further ten shillings at Christmas.13

The Company also spent money on occasional charitable gifts, particularly during times of hardship. In January 1709, for example, £30 was given to the poor of the Company "on account of the dearness and scarcity of bread, etc.", and in January 1722 £35 was distributed to poor members and widows. One-off donations were also occasionally given to charitable causes outside the Company: in 1752 it contributed five guineas to the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel, and in 1757-59 £150 was donated to the Marine Society.14

In the second half of the eighteenth century the amount spent on charity was reduced. In 1743 it decided to abolish payments at Christmas and St James's day and to gradually reduce the number of Company pensions from 100 to 60, as pensioners died. In 1752 regular payments of ten shillings per quarter to poor members of the Company were abolished, and in the same year the benefactors' pensions administered by the Company were cut from ten shillings per quarter to ten shillings per year.15

Whereas the Company had spent £357 on charity in 1739, it spent only £280 in 1743 and £252 in 1799.16 This was despite the fact that the Company's income grew from £750 a year at the beginning of the century to £1,300 in the later 1780s. By the end of the century more money was spent on Company dinners than on charity. In 1799-1800 for example, it spent £252 on charity and £333 on dinners.17 These sums do not include occasional charity: in 1800-1 the Company spent £114 13s 6d on "voluntary" charity on top of the £279 10s 5d spent on benefactions.18 Nonetheless, it is hard to resist the conclusion that the Company increasingly viewed charity as a lower priority than its other expenses.

Even at the end of the century, however, Company members benefited from extensive charity. With the Company's regulatory powers in decline, the primary benefits of membership lay in its non-economic functions: charity, sociabilty, and prestige.

Records of the Company's charity can be found in the Court of Assistants Minute Books (MC).

Documents Included on this Website

Introductory Reading

- Alford, Bernard W. E. and Barker, Theodore Cardwell. A History of the Carpenters' Company. 1968.

- McKellar, Elizabeth. The Birth of Modern London: The Development and Design of the City 1660-1720. Manchester, 1999.

- Ridley, Jasper. A History of the Carpenters' Company. 1995.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 R. Campbell, The London Tradesman (1747), pp. 160-61. ⇑

2 Edward Basil Jupp, An Historical Account of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters, 2nd edn., with suppl. by W.W. Pocock (1887), pp. 540, 579. ⇑

3 Jasper Ridley, A History of the Carpenters' Company (1995), pp. 86-89. ⇑

4 Leonard D. Schwarz, London in the Age of Industrialization: Entrepreneurs, Labour Force and Living Conditions, 1700-1850 (Cambridge, 1992), p. 21. ⇑

5 Joanna Innes, Inferior Politics: Social Problems and Social Policies in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford, 2009), ch. 7. ⇑

6 Bower Marsh, ed., Records of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters: Vol. 1: Apprentices' Entry Books, 1654-94 (Oxford, 1913), pp. 171-96. ⇑

7 J. R. Kellett, The Breakdown of Gild and Corporation Control over the Handicraft and Retail Trades in London, Economic History Review, 2nd series, 10 (1957-58), p. 389. ⇑

8 C. W. Brooks, Apprenticeship, Social Mobility and the Middling Sort, in J. Barry and C. W. Brooks, eds, The Middling Sort of People (Basingstoke, 1994), p.59. ⇑

9 Bernard W. E. Alford and Theodore Cardwell Barker, A History of the Carpenters' Company (1968), pp. 137-38 ⇑

10 C.R. Dobson, Masters and Journeymen: A Prehistory of Industrial Relations, 1717-1800 (1980), pp. 157-165. ⇑

11 Jupp, An Historical Account of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters, p. 644. ⇑

12 From the Company records, cited in Jupp, An Historical Account of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters, p. 314. ⇑

13 Alford and Barker, A History of the Carpenters' Company, p. 132. ⇑

14 Jupp, An Historical Account of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters, pp. 437, 555, 573. ⇑

15 Alford and Barker, A History of the Carpenters' Company, pp. 132-33. ⇑

16 Ridley, A History of the Carpenters' Company, p. 89. ⇑

17 Alford and Barker, A History of the Carpenters' Company, p. 129. ⇑

18 Jupp, An Historical Account of the Worshipful Company of Carpenters, p. 587. ⇑