Policing

Thomas Rowlandson. Beadle and Barrow Women. 1819. British Museum, British Roy PIV. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Thomas Rowlandson. Beadle and Barrow Women. 1819. British Museum, British Roy PIV. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Introduction

Traditionally, every male householder was expected to contribute to policing the streets, just as every citizen was expected to report and prosecute anyone they witnessed committing a felony. But, under the pressure of increasing concerns about the threat posed by violent and dangerous criminals, and owing to the growing wealth of London's middle classes, this changed in the eighteenth century. Just as Londoners became less willing to initiate prosecutions, with informers and thief-takers playing an increasingly important role, so too did householders withdraw from serving as night watchmen and constables, preferring instead to hire deputies or pay taxes to fund salaried officers to serve in their place. Similarly, instead of responding directly to crime, victims became more likely to summon help from the watch or thief-takers. In some respects the culmination of this process was the creation by Henry and John Fielding of the Bow Street Runners, part-publicly funded detectives under the direction of a magistrate, which rendered thief-taking more respectable. All these developments led to the increasing professionalisation of policing, anticipating most of the significant features of the Metropolitan Police, established in 1829. While improved levels of policing did not lead directly to increased numbers of prosecutions in the criminal courts, they did lead to significant changes in the character of criminal prosecutions and the criminal trial.

The Marylebone Watchhouse, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

The Marylebone Watchhouse, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

The Night Watch

Early modern householders were required to serve by rotation or appointment on the night watch, patrolling specified streets between 9 or 10 pm and sunrise. They were expected to examine all suspicious characters and to apprehend offenders and bring them to the watchhouse. In the City, they were appointed by the common council of each ward. In Westminster, watchmen fell under the joint control of the Court of Burgesses and the parish vestry, while in Middlesex they were appointed by the parish. The nightly work of watchmen was supervised by constables.

The duties of the watch were onerous and unpaid, and householders had to carry them out alongside their normal employment. Armed only with a staff, they were no match for violent criminals or drunken gentlemen wielding swords. It is not surprising, therefore, that from the seventeenth century increasing numbers chose to hire deputies to serve in their place. In fact, by the late seventeenth century this practice was so common in wealthier parts of London that the watch had essentially become a fully paid force.

The difficulties of supervising a force of deputies, each hired separately by a householder, and concerns about the rising tide of crime led parishes to obtain Watch Acts from Parliament, which authorised a parish to tax its residents in order to hire a salaried force of watchmen. Not surprisingly, the first two parishes to obtain such an act, in 1735, were the wealthy Westminster parishes of St James, Piccadilly and St George, Hanover Square. Over the remainder of the century, however, virtually every metropolitan parish acquired a Watch Act, so that by 1800 the vast majority of watchmen in London were paid a salary. St Clement Danes did not obtain an act until 1764. The City of London obtained its own act in 1737, which gave the City the power to specify the number of watchmen in each ward and gave the wards the power to levy rates to pay for them.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes Vestry Minutes, 4 January 1754, B1068, LL ref: WCCDMV362090299.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes Vestry Minutes, 4 January 1754, B1068, LL ref: WCCDMV362090299.

Further innovations occurred towards the end of the century. In 1774 the Westminster Watch Act set minimum standards in terms of the number of watchmen, their pay, and their basic duties, while still allowing the individual parishes control over their own watch. In 1785, in response to social anxieties sparked by the Gordon Riots and a post-war crime wave, the City created a City-wide Patrole with the responsibility to arrest vagrants and disorderly men and women and suppress minor disorders. Armed with a staff and a cutlass, and given a uniform of a blue coat and hat, the City Patrole anticipated many characteristics of the Metropolitan Police.1

It was not only local government which provided policing in London. In many places groups of private citizens or organisations formed their own watch schemes to supplement those provided by the parish and other units of local government. Wealthy residents of some streets and squares banded together to form their own watch, such as in "the Great Square" in St Giles in the Fields in 1691, while Societies for the Prosecution of Felons sometimes hired watchmen to patrol their areas. The trusts which built and ran turnpikes often provided patrols to ensure the safety of those who travelled on their roads (in addition, in 1782 the Treasury secretly paid for armed patrols on some of the roads leading into London and Westminster). Finally, in response to persistent pilfering and following the example of the special constables appointed by the Excise Office from 1711, the merchants who owned warehouses along the docks hired private watchmen to protect their goods.2 In 1798 the West India Merchants Committee funded a Marine Police Office to prevent property crime in the Port of London. In 1800 the office was given statutory footing and it was staffed with three magistrates and a large cohort of officers, funded by the government.

Parochial vestry minutes (MV) provide evidence of the regulation of the watch by parish officials, setting the number of watchmen, their hours, the location of their stands and their pay.

Impact of the Watch

Most of the changes to the watch in the eighteenth century were driven by the desire to combat property crime, particularly violent robbery. Together, they constitute a significant extension of police powers, anticipating many of the developments embodied in the Metropolitan Police in 1829. Like the Metropolitan Police, their efforts were primarily directed at the prevention of crime, not detection (for which see the Bow Street Runners below).

When suspicious or disorderly persons were arrested, watchmen typically brought them to the parish watchhouse, where they were kept until morning when tney could be examined by a Justice of the Peace and either discharged or sent to prison.

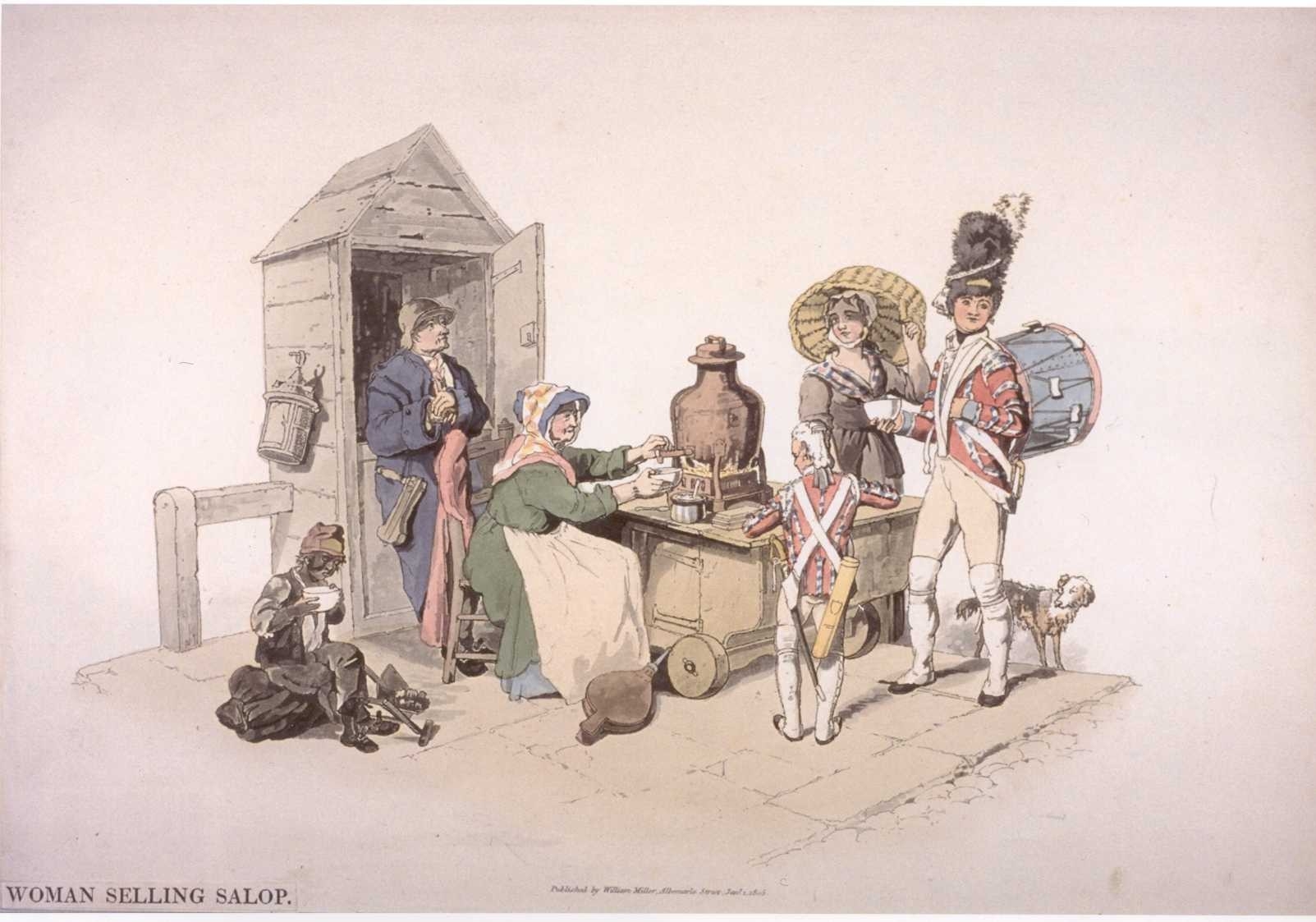

Woman Selling Salop. William Henry Pyne. The Costume of Great Britain. 1805. © London Lives.

Woman Selling Salop. William Henry Pyne. The Costume of Great Britain. 1805. © London Lives.

It is impossible to determine how effective the watch was. Although improvements to the watch cannot be correlated with increasing levels of prosecutions in the criminal courts, there is some evidence in the Old Bailey Proceedings that over the course of the century watchmen increasingly witnessed crimes and arrested offenders, and that victims of crime were increasingly likely to summon help from the watch. Certainly watchmen often testified in criminal trials.

But as suggested by the presence of watchmen in the records of Bridewell and individual parishes, the watch were involved in more than just apprehending serious property offenders. They were also an important and not always welcome presence in the lives of the poor. As indicated by the Minutes of the Court of Governors (MG) of Bridewell, the watch were often responsible for committing poor offenders accused of prostitution and "loose, idle and disorderly" conduct to Bridewell Prison.

Constables

The watch was supervised by constables, who also had the responsibility for executing warrants issued by Justices of the Peace, and for arresting anyone guilty of a crime, whether petty or serious, including vagrants and the "idle and disorderly". These powers were codified and extended by the 1744 Vagrancy Act, which gave constables the power to arrest anyone offending against a wide range of loosely defined categories of behaviour, and further empowered Justices of the Peace both to reward constables and punish petty offenders on their own authority.3 In addition, Justices of the Peace periodically ordered constables to sweep the streets and apprehend prostitutes, vagrants, "disorderly persons", gamblers and other offenders. They were also given orders to report to the Justices the names of people who committed various offences such as permitting excessive drinking in alehouses, profane swearers and cursers, those who worked on the sabbath, and a range of nuisance and regulatory offences.

Middlesex Orders of the Court, 23 February 1747, London Metropolitan Archives, MJ/OC/5, LL ref: LMSMGO556020253.

Middlesex Orders of the Court, 23 February 1747, London Metropolitan Archives, MJ/OC/5, LL ref: LMSMGO556020253.

In the City, constables were chosen by householders in the individual ward precincts, but due to the "custom of London", they had the power to act throughout the City, and had the power, unlike in the counties, to commit persons for suspicious behaviour on their own initiative, without a warrant from a Justice of the Peace. In Westminster, constables were appointed by the Court of Burgesses from lists of names provided by overseers of the poor, but since constables were frequently given orders (and sometimes removed) by Justices of the Peace, there was potential for conflict. In the rest of Middlesex constables were traditionally appointed by the manorial court leet, but as these courts had fallen into disuse in most parts of the metropolis these powers were largely taken over by Justices of the Peace. In both Westminster and Middlesex, constables were supervised by high constables, appointed by the Court of Burgesses in Westminster and by Sessions in Middlesex, where there was one high constable for each hundred. A particular responsibility of the high constables was to oversee the passing of rogues and vagrants back to their parishes of settlement.

Just like watchmen, and for many of the same reasons, many householders chosen for the office of constable preferred not to serve, and instead paid a fine or hired substitutes. Although they were already present in the late seventeenth century, the practice of hiring substitutes, or deputies, became more common in the first half of the eighteenth century. By 1730, four out of every ten constables in the City of London were hired, many of whom engaged in repeated service, often holding the post for years, effectively become professional policemen.4

Parochial Vestry Minutes (MV) provide evidence of this process. Those for St Dionis Backchurch document the meetings where constables were appointed, while those for St Botolph Aldgate list fines paid by men who preferred to pay a fine rather than serve, and those for St Clement Danes document decisions taken to approve substitutes to act in the place of the men nominated.

St Dionis Backchurch Vestry Minutes, 13 December 1750, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms 4216/3, LL ref: GLDBMV305010415.

St Dionis Backchurch Vestry Minutes, 13 December 1750, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms 4216/3, LL ref: GLDBMV305010415.

The different bodies constables were answerable to opened them up to conflicting orders, but perhaps this also gave constables some independence and room for manoeuvre. After 1792 the potential for conflict increased when a new group of constables was appointed, salaried officers attached to the Public Offices created by the Middlesex Justices Act.

In addition to parish constables, a number of special constables were appointed to maintain order in various contexts in London. In 1698 the porters of the London Workhouse were appointed as constables. From 1711 constables were appointed by the commissioners of excise for the port of London in order to prevent pilfering from the docks, and in the 1750s the West India Company appointed "merchants' constables" for the same purpose. In the early 1760s members of Society for the Reformation of Manners were sworn in by the City of London as extra constables for the prosecution of vice; these could act anywhere in the City.5 In the second half of the century the City appointed additional special or deputy constables in order to police crowds during public punishments and demonstrations, under the charge of the City Marshal. Their number expanded dramatically during the 1780s, following the Gordon Riots and the move of public executions to in front of Newgate Prison, and after 1793, owing to fears of insurrection prompted by the trials of members of the reform societies for high treason. The most important role of these constables, however, appears not to have been in preventing riot and disorder, but in arresting pickpockets and vagrants.6

The Work of Constables

Although frequently ordered by Justices of the Peace to sweep the streets and arrest offenders guilty of specific crimes, such as nightwalkers or vagrants, most constables adopted a reactive approach and only enforced the law in response to complaints from victims, or specific warrants issued by the Justices. As inhabitants of the very neighbourhoods they policed, and with the everpresent threat of violence or being subject to vexatious prosecutions from those they arrested, discretion was often the better part of valour.

Paul Sandby. The Well Fed English Constable. October 1777. This is almost certainly a depiction of William Payne, as it is similar to known satires of him. British Museum, BM Satires 4641. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Paul Sandby. The Well Fed English Constable. October 1777. This is almost certainly a depiction of William Payne, as it is similar to known satires of him. British Museum, BM Satires 4641. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Some constables, however, motivated by financial greed or religious zeal, adopted a more proactive approach and arrested hundreds of offenders for predominantly victimless offences. These men, such as William Payne, whose activities have recently been documented by Joanna Innes,7 often also acted as informers, and were supporters of a reformation of manners campaign. Although often reviled by those they prosecuted, such men could receive support from established householders concerned to maintain the respectability of their neighbourhoods.

Evidence of constables' activities can be found in a number of sources. Some of the fines they received for convicting persons for working on the sabbath can be found in Vestry Minutes (MV). Their arrests of persons accused of petty thefts, "loose, idle and disorderly conduct", prostitution, and other petty offences in the City of London can be found in the Minutes of the Bridewell Court of Governors (MG). Their arrests of suspected felons are documented in many of the depositions and informations contained in the manuscript Sessions Papers (PS) and in the printed Old Bailey Proceedings.

City Marshal

The City of London possessed additional law enforcement officers in the position of the City Marshal, a paid, uniformed officer who served under the Lord Mayor and had the responsibility to carry out the orders of City officials, supervise the night watch, and take up vagrants and other suspected criminals. The Marshal had an undermarshal and six men. He was given an enhanced role in the 1770s and leadership of the day patrol in 1785, by which point there were 10 men.8 The activities of the Marshals in apprehending offenders can be be found in the Old Bailey Proceedings.

Beadle - St Martins in the Fields. c.1800. © Westminster Archives Centre

Beadle - St Martins in the Fields. c.1800. © Westminster Archives Centre

Beadles

In some parts of London constables were assisted in their duties by beadles. A beadle was a minor officer employed to communicate orders and execute them, and can be found in a wide range of eighteenth-century institutions. In terms of policing, beadles carried out an important role in the City of London and Westminster, the focus of this section. Beadles also appear frequently in the records on this website as parish officers, responsible for summoning Coroners' Inquests (IC) and carrying out the orders of churchwardens and overseers of the poor, and as officers of Bridewell Hospital, implementing the orders of the Court of Governors.

Within the City, beadles were long-established ward officers. The office was a full-time job with a salary, and many served in the post for years, sometimes also acting as constables. Many had subordinates, called warders, who acted as their assistants. Their responsibilities included a range of policing activities: organising and supervising the night watch; controlling crowds; prohibiting the sale of goods on Sundays; prosecuting nuisances; arresting and prosecuting prostitutes, beggars and vagrants; and even arresting men and women on more serious charges. The Minutes of the Bridewell Court of Governors (MG) include many men and women accused of petty offences who had been committed directly by ward beadles (from 1785, however, beadles lost the power to make commitments on their own).

In Westminster, beadles were appointed by the Court of Burgesses and held similar responsibilities. They were expected to patrol the streets, drive out vagrants and beggars, and supervise the watch. In 1707, for example, the beadles were ordered to report all newcomers "so that the vast charge for the poor within the said several parishes may be in some measure prevented", and to go through the streets four times a day to prevent disorders and drive out vagrants and beggars.9

The Bow Street Runners

In 1749, prompted by a post-war crime wave and concerned about the failure of victims to prosecute criminals, Henry Fielding created the Bow Street Runners by paying retainers to a group of constables and ex-constables. Based at Fielding's house in Bow Street, their job was to locate and arrest serious offenders, and they were entitled to claim the government rewards payable on conviction. Although essentially thief-takers, Fielding hoped that his oversight of them would maintain their respectability and avoid the allegations of corruption which had dogged thief-takers. This was only partly successful, however, since many were former thief-takers and the runners needed connections in the criminal underworld in order successfully to identify suspects. Over time, however, they became more respectable, and respected.

St Botolph Aldgate Vestry Minutes, 26 October 1733. London Metropolitan Archives, Ms 2642/1, LL ref: GLBAMV114000162.

St Botolph Aldgate Vestry Minutes, 26 October 1733. London Metropolitan Archives, Ms 2642/1, LL ref: GLBAMV114000162.

Although Fielding obtained £200 from the government to help pay them, he soon ran out of money, and the runners had to subsist largely on official rewards and payments made by victims who hired their services. It was essential, therefore, that the public was aware of the runners, and resorted to the runners when they became victims of crime. To that end, Fielding placed advertisements in the newspapers encouraging the public to send a note to Bow Street as soon as any serious crime occurred, so that "a set of brave fellows" could "immediately" be despatched in pursuit of the villains.

When John Fielding took over Bow Street following his half-brother's death, he further developed these practices by establishing Bow Street as a central collection point for information about serious crimes which occurred all over the country. An alphabetical register was kept of all crimes and prosecutions, along with a register of stolen goods. Information about stolen goods and wanted criminals was widely circulated, leading eventually to the creation of the Police Gazette.

By the late eighteenth century the Bow Street Runners, as they came to be called, were essentially full-time policemen who served for many years. They were well known to the public through reports in the papers and their testimonies at Old Bailey trials, which were reported in the Old Bailey Proceedings. It is possible that their detailed testimonies, and regular cross-examinations by defence counsel, changed the nature of the criminal trial.

Fielding also expanded the role of the Runners by giving them the duty of patrolling major city streets and the principal roads leading into the metropolis in order to prevent robberies. Funding for this was only available erratically, when the government was particularly concerned about crime, for example in 1763 during the crime wave which followed the conclusion of the Seven Years War. In 1780, following the Gordon Riots, a patrol seems to have been set up on regular basis, and by 1797 the Bow Street office was home to sixty-eight patrol men, who patrolled in groups on horseback and on foot.10

Conclusion

In 1792, the Middlesex Justices Act created offices on the model of Bow Street across the metropolis. In response to the apparently ever growing threat of crime, the principle of using salaried officers both to prevent crime and to detect criminals had become firmly established in London, decades before the creation of the Metropolitan Police in 1829.

With several different types of police patrolling the streets or seeking out deviants, eighteenth-century London was hardly the weakly policed city some contemporaries complained of. But levels of policing varied significantly across the metropolis. With its Marshal and his officers, ward beadles, and Patrole, the City of London was subject to much greater levels of surveillance than the surrounding suburbs, though the affluent Westminster parishes which taxed themselves to provide a more regular watch were also relatively intensively policed. Even within the City, the ratio of constables to houses varied enormously from ward to ward, from only 28 houses per constable in the central ward of Bread Street, compared to 267 houses per constable at the other extreme in the extra-mural parish of Farrington Without.11

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keywords Bow Street Runners:

Introductory Reading

- Beattie, John M. Early Detection: The Bow Street Runners in Late Eighteenth-Century London. In Emsley, Clive and Shpayer-Makov, Haia eds, Police Detectives in History, 1750-1950. Aldershot, 2006, pp. 15-32.

- Beattie, J. M. Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror. Oxford, 2001.

- Harris, Andrew T. Policing the City: Crime and Legal Authority in London, 1780-1840. Columbus, Ohio, 2004.

- Reynolds, Elaine. Before the Bobbies: The Night Watch and Police Reform in Metropolitan London, 1720-1830. Stanford, 1998.

- Shoemaker, Robert B. The London Mob: Violence and Disorder in Eighteenth-Century England. London, 2004, chapter 2.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 Andrew T. Harris, Policing the City: Crime and Legal Authority in London, 1780-1840 (Columbus, Ohio, 2004), pp. 46-49. ⇑

2 Drew D. Gray, Crime, Prosecution and Social Relations: The Summary Courts of the City of London in the Late Eighteenth Century (Basingstoke, 2009), pp. 45, 56. ⇑

3 17 George II c. 5. ⇑

4 J. M. Beattie, Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror (Oxford, 2001), p.150. ⇑

5 Joanna Innes, Inferior Politics: Social Problems and Social Policies in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford, 2009), chap. 7. ⇑

6 Harris, Policing the City, p. 85. ⇑

7 Innes, Inferior Politics, chap. 7. ⇑

8 Beattie, Policing and Punishment, pp. 158-162. ⇑

9 Westminster Archives Centre, WCB3, Minute Book of the Westminster Court of Burgesses, 17 July 1707. ⇑

10 A. Babington, A House in Bow Street: Crime and the Magistracy in London, 1740-1881 (London, 1969), p. 176. ⇑

11 Gray, Crime, Prosecution and Social Relations, p. 61. ⇑