Prosecutors and Litigants

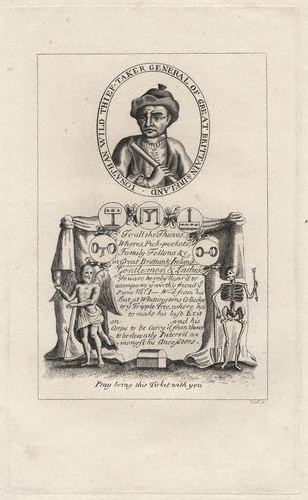

Jonathan Wild Thief-Taker General of Great Britain and Ireland. c.1725. © London Lives.

Jonathan Wild Thief-Taker General of Great Britain and Ireland. c.1725. © London Lives.

Introduction

The eighteenth-century legal system relied primarily on victims and other private individuals to initiate prosecutions. To counter the disincentives raised by the financial fees, time and potential damage to reputation entailed in mounting a prosecution, the government offered financial incentives, both in the form of rewards and the payment of expenses. Voluntary societies were also set up to support prosecutions. Despite these initiatives, however, many still found the costs outweighed the advantages of pursuing a formal prosecution. At the same time, the system of rewards offered the public, and even the poor, manifold possibilities to use the law for their own, sometimes illegitimate, ends.

Prosecutors

Since theoretically all English men and women were protected by the rule of law, everyone had the right to initiate a prosecution against those who had wronged them. Indeed, given the minimal police force available, the judicial system depended on private prosecutors for the enforcement of the law. Victims and witnesses of felonies were obliged to report the crimes they knew about and, if bound over by a Justice of the Peace, to prosecute the offender. But in practice, and although there was widespread knowledge about the law among plebeian Londoners, many lacked the financial resources required to carry out a formal criminal prosecution and deliberately avoided reporting crimes for fear of the expense of prosecuting. Virtually every step in the legal process involved paying fees, and it required a considerable investment of time to carry a prosecution through to the final stage of a criminal trial. Consequently, the majority of plaintiffs at courts such as the Old Bailey appear to have been from the middle classes - craftsmen, shopkeepers, and employers. Those from the lower classes, however, who had access to magistrate's courts were often able to get their complaints dealt with informally or summarily, even in felony cases, at a much lower price. In the City of London, for example, around 17-20 per cent of the litigants who brought complaints before the Lord Mayor and aldermen were the labouring poor, including servants prosecuting their employers for unpaid wages.1

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1722, MJ/SP/1722/10, LL ref: LMSMPS502060026.

London Metropolitan Archives, Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1722, MJ/SP/1722/10, LL ref: LMSMPS502060026.

Because the government was concerned that too many crimes, particularly felonies, went unpunished, accomplices were often given immunity from prosecution in return for turning king's evidence and informiong on their fellow criminals. The government also took steps to reimburse the costs of some prosecutors. Acts in the 1750s allowed judges to order the payment of prosecutors' costs for felony indictments which led to a conviction, and to reimburse the costs laid out by poor witnesses bound over to give evidence for the prosecution. In 1778 these provisions were extended to cases even where the defendant was not convicted. Consequently, by 1800 approximately two-thirds of prosecutors received some compensation for their costs.

In addition to government actions taken to help victims with the cost of prosecutions, potential prosecutors also banded together in Societies for the Prosecution of Felons in order to insure individual members against the financial burdens of going to court. These associations became common in England in the second half of the eighteenth century, and in London associations were formed of merchants concerned about the theft of goods from the docks (1749 and 1751); pawnbrokers who apprehended thieves trying to sell stolen goods (organised by Justice John Fielding, 1758); and tradesmen and shopkeepers concerned about frauds, forgeries and thefts committed against them (1767). Compared to the rest of the country, however, there were relatively few such societies in London, perhaps because so many prosecutions were carried out by men seeking rewards including thief-takers and the Bow Street Runners. Nonetheless, the societies provided a valuable resource for primarily middle class men who needed to initiate prosecutions. Unlike government assistance, these societies paid the costs of hiring lawyers, who came to take on an increasing role in the criminal trial over the course of the century.

Informers

The government had long used financial rewards as an encouragement to prosecute victimless crimes, offences against the community where no single individual could be identified as the victim and therefore no one had a direct motivation to prosecute. From the sixteenth century a number of statutes authorised the payment of half of the money raised from fines resulting from a conviction for violating economic regulations to those who initiated the prosecution. Those who benefited from these statutes, who came to be known as informers, were usually held in contempt by the local community as they were perceived to have profited from the misery of others, and were often accused of self-serving corruption. Nonetheless, successive statutes encouraged the practice of informing, including Restoration laws against religious dissenters and the eighteenth-century Gin Acts, and informers continued to prosper and to be reviled throughout this period. One of the reasons the reformation of manners campaign attracted such intense popular hostility was its heavy reliance on informers for initiating prosecutions against vice.

Motivated by financial incentives as well as (on occasion) religious zealotry, informers can be found prosecuting a wide range of offences, and combining private activities with service in local government offices. One particularly active informer who frequently appears in the documents on this website is William Payne, a carpenter, whose activities have recently been analysed by Joanna Innes.2 Payne was a Methodist and a member of a reformation of manners society. But, in part because he served as a headborough, constable, and marshalman, he was involved in a much wider range of criminal prosecutions than these affiliations alone suggest, being responsible for numerous arrests and prosecutions at various times over twenty years for prostitution, keeping disorderly houses, pickpocketing, breaching building regulations, forestalling, Catholicism, riot, returning from transportation, coining, and arson. Payne's extensive activities suggest that he was motivated by a sense of civic duty, as well as by religious zeal and/or a desire for profit.

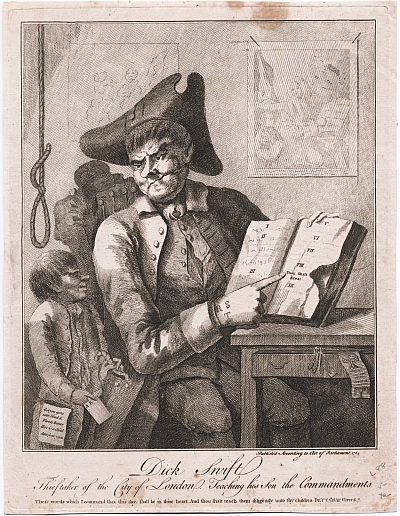

Dick Swift Thieftaker of the City of London Teaching his Son the Commandments. 1765. British Museum, Satires 4120. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Dick Swift Thieftaker of the City of London Teaching his Son the Commandments. 1765. British Museum, Satires 4120. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Thief-Takers

Prior to the end of the seventeenth century rewards were less frequently provided for convicting those guilty of felonies since victims of serious crimes were legally required to prosecute the culprits. But concerns about the growth of crime and the disinclination of victims to prosecute led Parliament after 1689 to pass a series of statutes offering substantial rewards for information leading to the conviction of those guilty of specific felonies.

The first permanent act, passed in 1692, offered a reward of £40, plus the offender's horse, arms and money if they were not stolen, for the conviction of highway robbers. This was followed over the ensuing decades by similar rewards for the conviction of those found guilty of counterfeiting, shoplifting, burglary, house-breaking, horse, sheep and cattle theft, and returning from transportation. Royal proclamations temporarily increased the reward for certain offences during perceived crime waves. In 1720, for instance, an additional £100 was promised to prosecutors for those convicted of highway robbery in and around London. When combined with the permanent reward, this and successor proclamations meant that between 1720 and 1745, and 1750 and 1752, the reward for a conviction of a robber in London was £140.

This was a huge sum, and contributed to the phenomenon of thief-takers, men (and occasionally women) who earned their livelihoods both from the rewards gained from convicting offenders on these statutes, and from private rewards offered by victims to those who could broker the return of stolen goods, no questions asked. Needing access to knowledge about criminal activities, thief-takers flourished on the boundaries of legal and illegal activity, profiting in turn both from arresting serious criminals and from brokering the return of stolen goods for a fee. Although widely acknowledged to be corrupt, the authorities nonetheless tolerated thief-takers owing to their prominent role in the arrest of serious criminals.

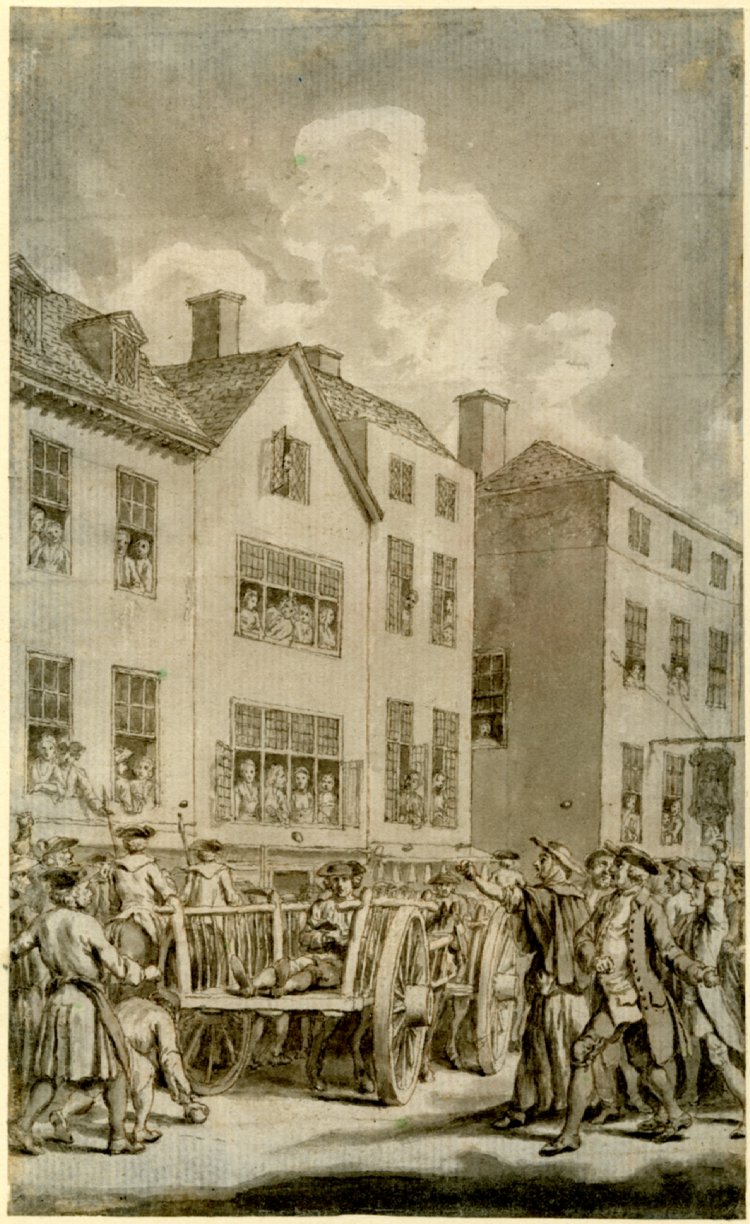

Samuel Wale. Jonathan Wild Pelted by the Mob on his way to Execution in 1725. Mid-eighteenth century. British Museum, Binyon 3. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Samuel Wale. Jonathan Wild Pelted by the Mob on his way to Execution in 1725. Mid-eighteenth century. British Museum, Binyon 3. © Trustees of the British Museum.

In the 1690s and early eighteenth century, some thirty to forty thief-takers flourished in London, some of whom were also constables and/or informers working for the reformation of manners campaign. Salathiel Lovell, City Recorder from 1692 to 1708, allegedly encouraged thief-taking and profited directly from their activities. In the early 1720s Jonathan Wild combined all aspects of the thief-taker's trade to organise an extensive criminal network of thieves and thief-takers, styling himself "Thief-taker General of England and Ireland". Concerns about the practice of accepting rewards for the return of stolen goods without prosecution led to the inclusion of a clause outlawing the practice in the first Transportation Act (1718), which became known as "Jonathan Wild's Act", and in 1725 Wild was himself convicted under this act and executed.

Despite the contempt in which thief-takers were held, particularly following Wild's abuse of the system, the practice continued because the authorities still needed it. At mid century there were at least two dozen thief-takers in the metropolis, many of whom were constables. As Ruth Paley has demonstrated, their ability to initiate vexatious prosecutions allowed them to "turn the legal system into what was, in effect, a sophisticated offensive weapon".3 By creating the Bow Street Runners, Henry Fielding attempted to bring thief-takers under the control of a magistrate, but he was forced to work within existing networks and he was not entirely successful in preventing corruption. Aware of the fact that the prospect of a substantial reward encouraged perjury, the government placed restrictions on the granting of rewards, and the £100 additional rewards which had been available for several decades following 1720 were abandoned in the early 1750s. This did not prevent the McDaniel Gang scandal of 1756, when four men were found guilty of encouraging two others to commit a robbery so that they could arrest them and profit from the reward when they were convicted. Although convicted, the four men were not hanged, probably in order to play down the role of the magistracy in the scandal.

Despite the McDaniel case, thief-takers were still a useful instrument of policing and they continued to operate during the second half of the century, with occasional further "thief-making" scandals coming to light. But partly owing to the work of John Fielding but also due to the increased presence of defence council in trials and the adoption of more stringent rules of evidence, the worst abuses of thief-takers were curtailed. By the end of the century a process of professionalization had taken place. With the passage of the Middlesex Justices Act in 1792, constables were given salaries and subjected to greater judicial oversight, and the era of the independent thief-taker was over.

London Metropolitan Archives Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1750, MJ/SP/1750/07, LL ref: LMSMPS504040017.

London Metropolitan Archives Middlesex Sessions of the Peace, Sessions Papers, 1750, MJ/SP/1750/07, LL ref: LMSMPS504040017.

Vexatious Prosecutions

Stimulated by the rewards available, and facilitated by the large number of different courts in London using three different legal systems (criminal, civil and ecclesiastical), vexatious or malicious prosecutions were endemic in the eighteenth century. As with thief-takers, prosecutions could be initiated merely for profit, but they could also be used as a means of exacting vengeance or of putting pressure on one's enemies. Knowledge of the law was widespread, and Londoners appear to have believed that it was easy to procure perjured testimony in order to sustain a false prosecution. Such prosecutions most frequently involved accusations of assault and small debts and were often undertaken in order to force the victims to drop prosecutions in progress.

In their simplest form, these vexatious prosecutions involved testifying before a Justice of the Peace that someone had threatened to break the peace, as a means of having them bound over by recognizance. For the poor, this could have serious implications, since a recognizance required you to find sureties of your good behaviour, and if you failed it could result in imprisonment. Trading Justices were accused of encouraging such prosecutions, because they profited from the fees.

Alternatively, one could file an indictment for an offence such as perjury, forcible entry, defamation, petty theft, or assault. The legal definition of assault in particular was sufficiently vague that a wide range of conduct, often involving no physical violence whatsoever, could be alleged against the defendant, and it has been argued that most prosecutions for assault were essentially civil suits, in which the plaintiff sought compensation rather than a conviction,4 or sought to force the defendant to compromise or drop another prosecution. It was alleged that these vexatious prosecutions were often encouraged by so-called Newgate Solicitors, who frequented the prisons and the courts looking for individuals accused of crime who could be encouraged to mount a counter-suit in response.

Another very simple form of vexatious litigation was to swear a false action for debt, forcing the victim to be incarcerated in a debtors' prison unless they were able to produce a specified sum of money, and associated fees, immediately. Defending oneself against such actions was very expensive, and therefore the victim had a strong incentive to meet the demands of their antagonist. Acts passed by Parliament, such as the Vexatious Arrests Act of 1726, made such vexatious prosecutions more difficult, particularly as arrests for debts below forty shillings were prohibited, but they nonetheless continued.

There is evidence of vexatious prosecutions being used in a number of different contexts in eighteenth-century London:

- to resist a legitimate prosecution. The Court Justice Thomas DeVeil complained that members of criminal gangs, assisted by "Newgate Solicitors", "were always endeavouring to obstruct justice, and [DeVeil] was in a manner continually beset by them, who were watching all opportunities to bring actions against him if he made a false step, or to plague and harass those honest prosecutors that were going to discover their villanies, or those of their clients".5 Not only would such men "swear anything to perfect their designs", but they were always on the lookout to catch Justices who failed to follow the correct procedures, for example by acting outside their jurisdiction. In 1742, when the government ordered a crackdown on street crime in Covent Garden, the Middlesex Justices were assured that they would be indemnified against the vexatious prosecutions that would inevitably follow.

- to oppose campaigns against vice. A major reason why the reformation of manners campaigns of the eighteenth century achieved so little was that the informers, officers, and Justices of the Peace who supported them were so often subjected to vexatious suits. When the Westminster Justices initiated a campaign against "disorderly houses" around 1730, the offenders targetted, notably Mary Harvey, were able to fight back by prosecuting the constables who searched their houses and arrested them for assault and false arrest.6 Although such prosecutions often failed, defending them was time-consuming and expensive for law enforcement officials.

- to resist impressment in the Navy. Men apprehended by press gangs frequently sued officers for trespass, assault, or false imprisonment.7

- to use the law as a political weapon. In the 1760s and 1770s, the supporters of the radical John Wilkes were adept at using vexatious prosecutions to challenge the authorities, for example by prosecuting Justices of the Peace and soldiers for murder when rioters were killed, and by countersuing officials for assault and false arrest. By exploiting the principle that all Englishmen had equal access to the law, they managed to place the government on the defensive and to demonstrate to the public that the law could be used effectively to challenge the authorities. Concerns about such challenges help explain why magistrates were so reluctant to oppose the Gordon Rioters in 1780.8

In sum, even though access to the law was difficult for the poor, they could nevertheless use the law aggressively. Vexatious prosecutions were facilitated by the essentially private character of eighteenth-century litigation, the lucrative opportunities for rewards, and the support of those who stood to profit from prosecutions, including "Newgate Solicitors" and trading Justices. While the wealthy had greater access to the legal system, the surprising fact is that Londoners of all social classes were able to manipulate the law for their own ends. In the long term, efforts to eliminate abuses led to a more bureaucratic legal system with reduced public involvement, but in the eighteenth century the possibilities offered by litigation in the courts were more open ended.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keywords King's Evidence:

Lives using the keywords Jonathan Wild:

Lives using the keyword Reward:

Lives using the keyword Thief-taker:

Lives using the keywords Vexatious Prosecution:

Introductory Reading

- Beattie, J. M. Crime and the Courts in England 1660-1800. Princeton, 1986.

- Hay, Douglas. Prosecution and Power: Malicious Prosecution in the English Courts, 1750-1850. In Hay, D. and Snyder, F. eds, Policing and Prosecution in Britain 1750-1850. Oxford, 1989, pp. 343-96.

- Howson, Gerald. Thief-Taker General: The Rise and Fall of Jonathan Wild. 1970.

- Paley, Ruth. Thief-Takers in London in the Age of the McDaniel Gang, c. 1745-1754. In Hay, D. and Snyder, F. eds Policing and Prosecution in Britain 1750-1850. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1989, pp. 301-42.

- Philips. David. Good Men to Associate and Bad Men to Conspire: Associations for the Prosecution of Felons in England, 1760-1860. In Hay, D. and Snyder, F. eds, Policing and Prosecution in Britain 1750-1850. Oxford, 1989, pp. 113-70.

- Shoemaker, Robert B. The London Mob: Violence and Disorder in Eighteenth-Century England. 2004, chap. 8.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography

Footnotes

1 Drew D. Gray, Crime, Prosecution and Social Relations: The Summary Courts of the City of London in the Late Eighteenth Century (Basingstoke, 2009), pp. 159, 169. ⇑

2 Joanna Innes, Inferior Politics: Social Problems and Social Policies in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford, 2009), chap. 7. ⇑

3 Ruth Paley, Thief-Takers in London in the Age of the McDaniel Gang, c. 1745-1754, in D. Hay and F. Snyder, eds, Policing and Prosecution in Britain 1750-1850 (Oxford, 1989), pp. 312. ⇑

4 Norma Landau, Indictment for Fun and Profit: A Prosecutor's Reward at Eighteenth-Century Quarter Sessions, Law and History Review, 17 (1999), pp. 507-36. ⇑

5 Thomas DeVeil, Observations on the Practice of a Justice of the Peace (1747), p. vii. ⇑

6 Heather Shore, 'The Reckoning': Disorderly Women, Informing Constables, and the Westminster Justices, 1727-33, Social History, 34 (2009), pp. 409-27. ⇑

7 Nicholas Rogers, Impressment and the Law in Eighteenth-Century Britain, in Norma Landau, ed., Law, Crime and English society, 1660-1830 (Cambridge, 2002), pp. 71-94. ⇑

8 John Brewer, The Wilkites and the Law, 1763-74, in John Brewer and John Styles, eds, An Ungovernable People? The English and their Law in the seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries (London, 1980), p. 145. ⇑