Ordinary's Accounts: Biographies of Executed Convicts (OA)

Biographies of Executed Criminals, 1676-1772

A sister publication of the Old Bailey Proceedings, the Ordinary’s Accounts, containing biographies of the prisoners executed at Tyburn, were regularly published during the century following the inception of the Old Bailey Proceedings. The Accounts are a valuable source of information about the lives, attitudes, and dying behaviour of executed convicts, and form an excellent starting point for assembling biographies of plebeian Londoners. Along with the Old Bailey Online, this website includes all surviving Accounts relating to convicts tried at regular sessions of the Old Bailey court which were published under the name of the Ordinary of Newgate.

The Ordinary and his Account

The Ordinary of Newgate was the chaplain of Newgate prison, and it was his duty to provide spiritual care to prisoners who were condemned to death. One of the perquisites of the Ordinary's position was the right to publish an account of the prisoners’ last dying speeches and behaviour on the scaffold, together with stories of their lives and crimes. Sold at the affordable price of three or six pence, print runs ran into the thousands. As a result, this was a profitable sideline for the Ordinary, earning him up to £200 a year in the early eighteenth century. He published The Ordinary of Newgate's Account of the Behaviour, Confession and Dying Words of the Condemned Criminals ... Executed at Tyburn (titles varied slightly) following almost every hanging day at Tyburn, and over 450 editions were published, containing biographies of some 2,500 executed criminals.1

Most of the Accounts follow a similar format. They include a short summary of the names and crimes of those sentenced to death (including convicts subsequently reprieved), accounts of the Ordinary's sermon and his visits to the condemned prisoners, short biographical sketches of each criminal, and a description of their final confessions and behaviour at their executions.

The earliest Accounts were compiled by Samuel Smith, Ordinary between 1676 and 1698, and from 1684 publication came under the control of the City of London. Early eighteenth-century Accounts compiled by Paul Lorrain (Ordinary between 1700 and 1719) often include advertisements, but these appeared less often in the 1720s. Between 1732 and 1744 under James Guthrie (Ordinary from 1734 to 1746) an Appendix was added, sometimes as long as forty pages, containing additional material (such as correspondence) relating to the convicts. From 1745 both the sermon and the appendix were abandoned, with the former replaced with an essay. In these later Accounts more attention was focused on the crimes and trials of the condemned rather than their confessions.

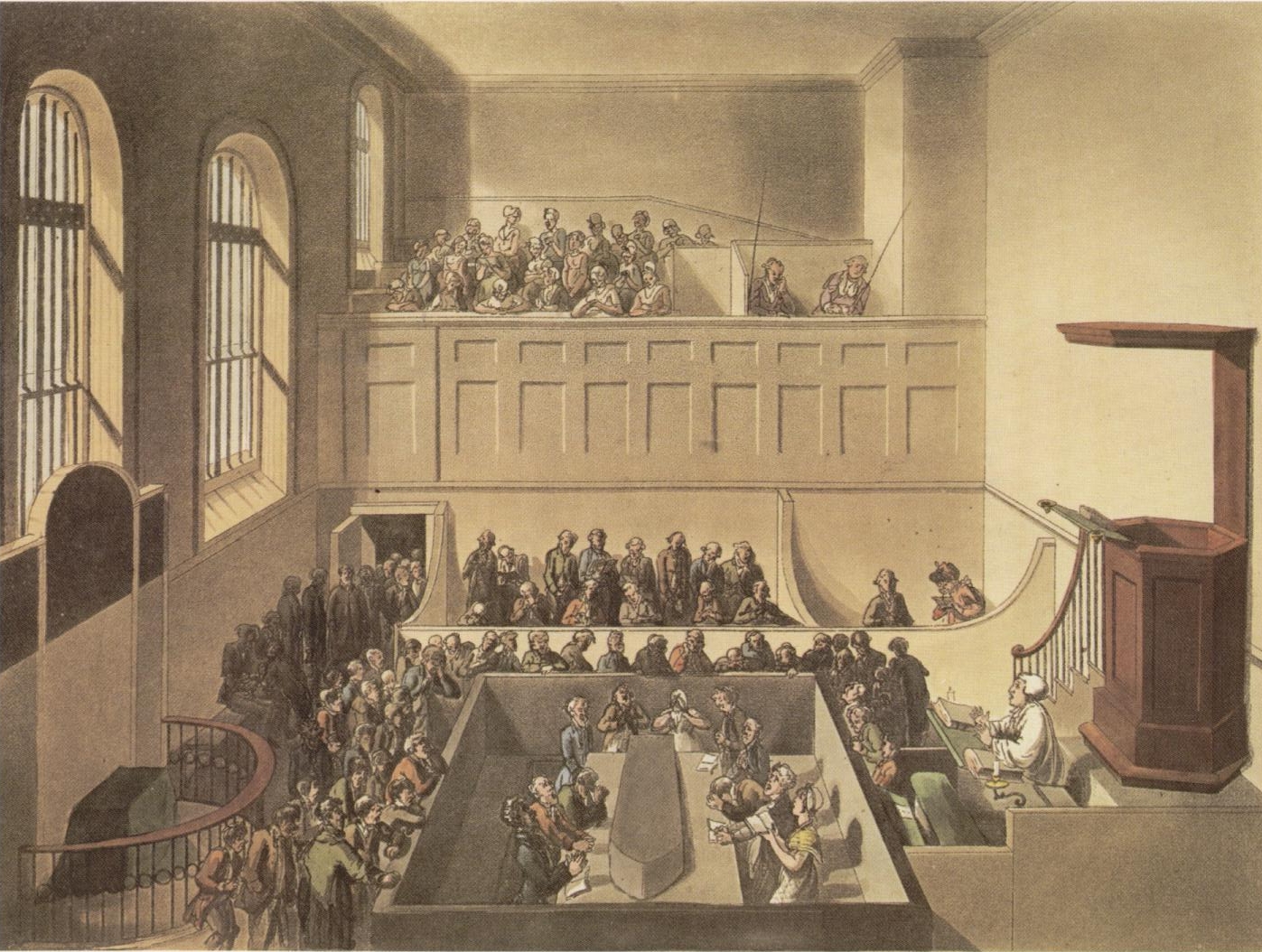

Thomas Rowlandson. Newgate Prison, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. ©London Lives.

Thomas Rowlandson. Newgate Prison, from The Microcosm of London, 1808. ©London Lives.

Moral Purpose

Even more than other criminal biographies, the Accounts had the explicit moral purpose of teaching readers the wages of sin. The accounts of the convicts' lives usually outline their descent down the slippery slope of immorality from minor delinquencies such as idleness and profaning the Sabbath into a life of increasingly serious crime. By rehearsing the sources of criminality the Ordinary demonstrated the dangers and temptations to sin faced by all men and women, including respectable readers of the Accounts.

Not only did everyone face these dangers, but the Accounts showed that redemption was also available to all. By forcing the condemned to come to terms with their guilt and accept the court's judgement passed upon them, the Ordinary attempted to reintegrate them back into the community. By confessing their crimes, and hopefully even providing details of accomplices who had not yet been captured, criminals could repay their debt to society and prepare themselves for salvation. While their lives served as salutary warnings, accounts of their deaths provided reassurance of God’s benevolence.

The Convict’s Story

The biographies of the condemned were shaped to provide an instructive moral lesson. Nonetheless, research conducted by Peter Linebaugh indicates that most of the details of their lives in the Accounts, many of which could only have been provided by the convicts themselves, are reliable. These include their place and date of birth, occupation, religion, and account of crimes committed.2

The Ordinary did not alter significantly the convicts' accounts of their lives and their explanations of their crimes. Because he sought both to entertain his readers and to show that convicts under his care were truly repentant, he had to allow them to speak in what was sometimes described (in order to validate their authenticity) as almost in their own words. While the Ordinaries occasionally criticised and sarcastically commented on these stories they nonetheless included them, because they formed part of the Ordinary's own story of how he had brought recalcitrant sinners to repentance. In telling their stories, convicts were able to introduce mitigating factors in justification of their crimes and even proclaim their innocence of the specific crime for which they were condemned, while always acknowledging their general sinfulness and sincere repentance. Although often written in the third person, these texts provide a unique insight into the minds and life stories of eighteenth-century criminals, and are therefore a valuable source for researching the history of crime.

Not all convicts chose to co-operate with the Ordinary, whether because they were not Anglican or because they resented the fact that he would profit from their misery. But most did, because the Accounts gave them the opportunity to tell their side of the story, and to preserve what was left of their reputations from misrepresentation by others.

Decline

For some, the Ordinary’s morality was dubious. Not only did he profit from the deaths of his charges, but there were allegations that the Ordinaries were corrupt, and only published the convicts' own words if they were suitably bribed, although we should note that these complaints typically came from the authors of competing accounts. Further competition came from ministers of other denominations, including Catholics, Jews and Methodists, who from 1735 were also able to counsel the condemned in Newgate.

Detail from William Hogarth's finished drawing for Plate 11 of "Industry and Idleness" (1747), "The Idle 'Prentice Executed at Tyburn". British Museum, Binyon 14, Croft-Murray (unpublished) 41, Oppe 63. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Detail from William Hogarth's finished drawing for Plate 11 of "Industry and Idleness" (1747), "The Idle 'Prentice Executed at Tyburn". British Museum, Binyon 14, Croft-Murray (unpublished) 41, Oppe 63. © Trustees of the British Museum.

In plate 11 of William Hogarth's Industry and Idleness (1747), the Ordinary is depicted inside a coach near the centre of the image, between the cart carrying the condemned Tom Idle and the Tyburn scaffold. He is staring disconcertingly directly at the viewer from inside his coach, while the man who is actually ministering to Tom in the cart is a Methodist preacher. Reflecting the competition the Ordinary faced from other publishers who rushed to sell their own accounts, just below him in the forefront of the image is a woman who is already selling Tom's last dying speech before he has even reached the scaffold.

In addition to increasing competition, in the 1760s the Ordinary had to cope with the decline of popular demand for this type of literature. In the early 1770s the Accounts ceased to be published regularly, though the publication was occasionally revived for special cases. The related genre of the last dying speech continued to prosper, while criminal biographies were often published in collections of the lives of notorious criminals such as The Newgate Calendar, first published in 1773. John Villette, Ordinary between 1774 and 1799 and publisher of the last example of this genre in 1777, compiled a similar collection, the four volume Annals of Newgate, in 1776.

Links to the Old Bailey Proceedings

All the subjects of the Ordinary's Accounts were tried and convicted at the Old Bailey, and therefore their trials should be recorded in the Old Bailey Proceedings. However, not all these trials can be found since many editions of the Proceedings before 1714 do not survive, particularly those published between 1699 and 1714.

There are three ways to find the relevant trial for a convict who appears in the Ordinary's Accounts.

- Use the Person Name Search page, narrowing your search to the Proceedings and to the twelve months before the execution. Use metaphone searching to allow for variant name spellings.

- Look up the name in the Associated Records Database. If a trial account survives, it should be listed with the trial reference number.

- Go to the Old Bailey Online, find the relevant Ordinary's Account, and check the trial reference numbers listed at the top of the page.

As is evident from the biographies included on this website, names appearing in the Accounts also appear in many of the other documents in London Lives.

Introductory Reading

- Faller, L. B. Turned to Account: The Forms and Functions of Criminal Biography in Late Seventeenth- and Early Eighteenth-Century England. Cambridge, 1987.

- Linebaugh, Peter. The Ordinary of Newgate and his Account. In Cockburn, J. S., ed., Crime in England 1550-1800. 1977.

- McKenzie, Andrea. From True Confessions to True Reporting? The Decline and Fall of the Ordinary’s Account. London Journal, 30:1 (2005), pp. 55-70.

- McKenzie, Andrea. Tyburn's Martyrs: Execution in England 1675-1775. 2007.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Documents Included on this Website

London Lives includes all surviving copies of the Ordinary's Accounts, defined as those relating to convicts tried at regular sessions of the Old Bailey court which were published under the name of the Ordinary of Newgate, published from 1680. For earlier Accounts, and a list of all surviving editions, see the Old Bailey Online. If you are aware of a copy of an Ordinary's Account which is not included, please contact us.

Footnotes

1 For a comprehensive account of this genre, see Andrea McKenzie, Tyburn's Martyrs: Execution in England 1675-1775 (2007). ⇑

2 Peter Linebaugh, The Ordinary of Newgate and his Account, in J. S. Cockburn, ed., Crime in England 1550-1800 (1977), pp. 246-69. ⇑