St Botolph Aldgate

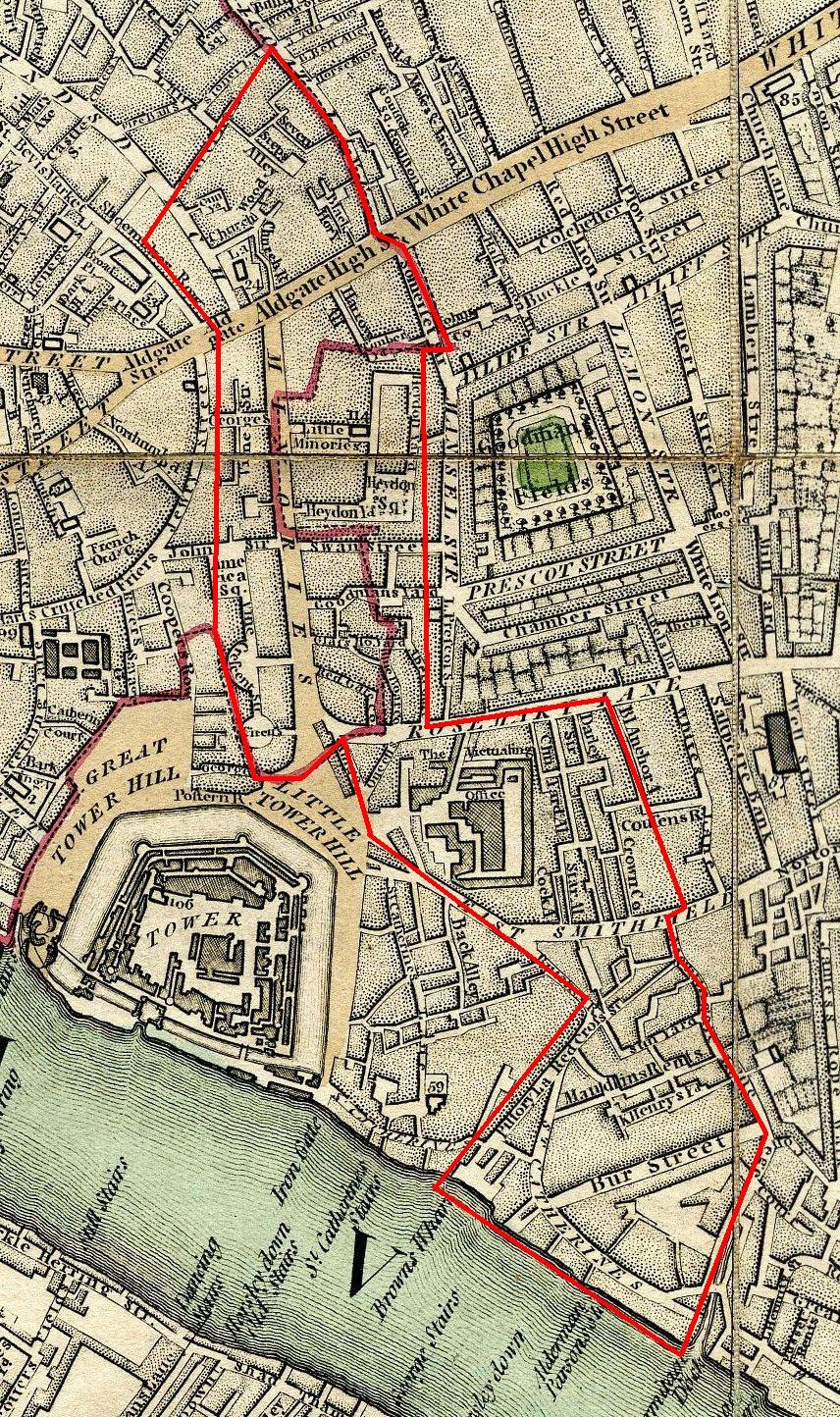

St Botolph Aldgate; Cary's New And Accurate Plan Of London And Westminster 1795. © MAPCO 2006 (base map only).

St Botolph Aldgate; Cary's New And Accurate Plan Of London And Westminster 1795. © MAPCO 2006 (base map only).

Introduction

Straddling the eastern boundary between the City of London and Middlesex, St Botolph was a large and densely packed parish. Already substantially built up by the late seventeenth century, it experienced modest population growth in the eighteenth century in the form of an increasing density of persons per house, reflecting in turn a decline in the social status of its residents. The parish suffered considerable poverty, disease and poor housing, but there was also a significant minority of wealthier inhabitants, substantial poor relief and a high level of charitable giving. Despite the deprivation, crime does not appear to have been a significant problem, or at least the inhabitants appear to have been able to resolve their difficulties without frequent resort to the courts. Overall, despite its poverty and divided government, the parish seems to have experienced social stability.

Location

St Botolph Aldgate is located on the eastern edge of the City of London, straddling the border with Middlesex; part of the parish was in the City (in Portsoken Ward), and part in Middlesex (East Smithfield). A long, thin parish, it stretched from Gravel Lane (off Houndsditch) in the northeast all the way to the Thames in the south. The northern part of the parish, located in the City, was bordered by Petticoat Lane, Somerset Street and Mansell Street on the northeast side, and Houndsditch and Vine Street on the west, continuing south down the Minories and bypassing the Liberty of Trinity Minories towards Tower Hill and Rosemary Lane. The southern part, only attached to the rest of the parish across a short stretch of Rosemary Lane, was in Middlesex, and located east of the Tower of London and the parish of St Katherine by the Tower. With King Street and Ditch Side on its western border, its eastern boundary went along Darby Street, Church Yard Alley, Black Dogg Alley, and Nightingale Lane down to the Hermitage Dock. On the west, it was bordered by East Smithfield (the street), Butcher Row, and Red Cross Street.

Local Government

Government of the parish was divided. Each half had its own vestry, though there were also combined meetings. The City part of the parish, sometimes called the Freedom part, fell within Portsoken Ward, which had its own set of ward officers, including an alderman, five common council men, five constables, nineteen inquest men, five scavengers, and a beadle. The remainder of the parish, sometimes called the Lordship part because it was within the Manor of East Smithfield, fell under the jurisdiction of the Middlesex Sessions, which had responsibility for ensuring law and order in the county.

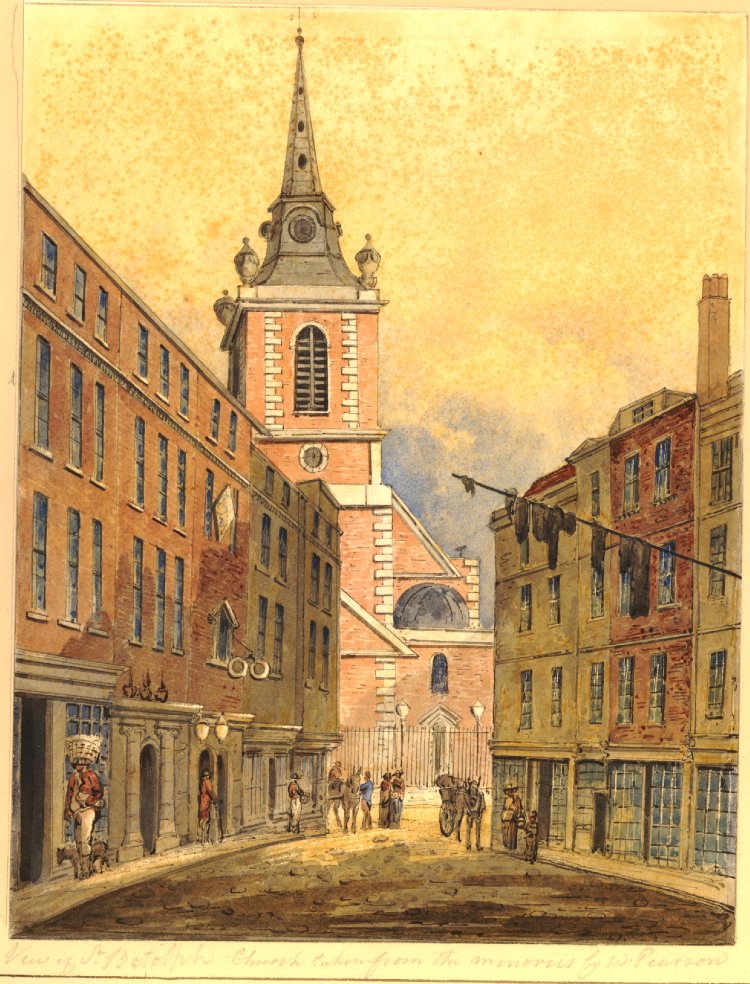

William Pearson, Old Houses on the North West Corner of the Minories and Aldgate. 1810. British Museum, Binyon 22, Crace XXIII.92. © Trustees of the British Museum.

William Pearson, Old Houses on the North West Corner of the Minories and Aldgate. 1810. British Museum, Binyon 22, Crace XXIII.92. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The allocation of poor relief was for the most part conducted by separate churchwardens and overseers of the poor for the City and Middlesex parts of the parish, and appeals to the decisions of these officers were accordingly heard by the common council men of the ward in the City and Justices of the Peace at their Sessions in Middlesex. Accounts of the business of these churchwardens and overseers of the poor can be found in Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor Account Books (AC). Parish properties, legacies, and rentals, however, were managed by separate "renter churchwardens" for the whole parish, and their accounts can be found in the Miscellaneous Parish Account Books (AO).

Parish government was largely hierarchical. According to William Maitland, "the vestry [of the City part] is neither select nor general, all being admitted who have either served or fined for offices".1 This was a limited group: only a small proportion of the inhabitants, two or three per cent, had the property qualification necessary to serve on the vestry.2 Members of the vestry were thus likely to be middle-class men such as shopkeepers. Nonetheless, some parish officers were elected by parish inhabitants.

In terms of religious administration, the parish was united, and fell within the jurisdiction of the Diocese of London. Reflecting the earlier puritan character of the parish, in the early eighteenth century it was home to two activist ministers. Both White Kennett, minister from 1700 to 1707, and Thomas Bray, minister from 1708 to 1730, were heavily involved in the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG), the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK), and the Societies for a Reformation of Manners. Bray was also involved in investigating prison conditions, soliciting funds for the relief of poor prisoners, and supporting missionary work in America. He was also known for his devotion to his parochial duties, particularly the catechisms he devised for charity school children and workhouse inmates. He contributed to the building of a new parish church by agreeing to forego some of the rents owed to him as rector, although this project did not come to fruition until 1744.3

Population

Following extensive growth in the seventeenth century, the population of the parish grew slowly in the eighteenth century. According to the 1695 Marriage Duty Tax, which was effectively a census, the parish contained 12,783 inhabitants in 1694, divided between 7,880 in the City part of the parish and 4,906 in the Middlesex part. According to the 1801 census, the population of the City part had increased by 10 per cent to 8,689, while the Middlesex part grew faster, by 25 per cent to 6,153, making the parish total 14,842, 16 per cent higher than in 1694.4

Thomas Rowlandson, Ragfair, Rosemary Lane, n.d., late eighteenth century. British Museum, Binyon 44, Crace XX.188. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Thomas Rowlandson, Ragfair, Rosemary Lane, n.d., late eighteenth century. British Museum, Binyon 44, Crace XX.188. © Trustees of the British Museum.

It was a densely populated parish, with part of the parish described in 1739 as "one of the most populous places within the bills of mortality" (the whole built-up area of London).5 Despite the relatively small size of its houses, in Tower precinct (the relatively poor southern portion of the City part of the parish) there were an average of 4.5 inhabitants per house, and 1.7 households per house, in 1694 (according to the Marriage Duty Tax). With a mean household size of 2.5 and family size of 2.3, there were relatively few apprentices, servants, and lodgers. Reflecting the relatively unconventional nature of London households at the time, 50 per cent of the family groups did not include a married couple and 60 per cent had no children.6

Estimates of the number of houses in the parish remain remarkably constant at around 2,500 throughout the century, which means the number inhabitants per house increased. In the Middlesex part of the parish this increased from 3.95 in 1694 to 5.61 in the 1801 census, and 7.4 in the City part of the parish. This was partly because families grew larger,7 and partly because more families (or individual lodgers) were squeezed into each house. There was an average of 1.6 families per house in the Middlesex part in 1801, and only 25 of the 1,097 houses were empty.8

Distribution of Wealth

Reflecting its liminal character on the border between the relatively wealthy City and the poorer East End Middlesex parishes, St Botolph contained a mixture of social classes, but it was dominated by working people. Compared to the rest of the City, its rental values were low, and large numbers of households were identified in tax records as poor. Within the parish, the City part was wealthier than the Middlesex part.

According to the 1666 Hearth Tax, the mean number of hearths per household in the parish was 2.5, lower than virtually all City and Westminster parishes; 27 per cent of the households had only a single hearth, and 33 per cent two hearths. The relative poverty of the area ensured that this tax could not be collected from three-fifths of the households, of which 20 per cent were listed as not having enough goods to seize for non-payment, 27 per cent were "not chargeable", and 15 per cent were "poor". There were, nonetheless, a small number of wealthy households, with 11 per cent of households having five or more hearths. Few of these, however, were aristocratic: only 0.1 per cent of householders were titled.9

Paul Sandby, Old Clothes to Sell, 1759. © Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery.

Paul Sandby, Old Clothes to Sell, 1759. © Nottingham Castle Museum and Art Gallery.

This picture is reinforced by the evidence gathered for the Four Shillings in the Pound Tax in 1694 and the Marriage Duty Tax in 1695. Both rental values and the amount of "stocks" (cash or moveable goods) per household were lower than most of the rest of the metropolis, though 39 per cent of the households in Portsoken Ward and 22 per cent of the households in the Middlesex part of the parish possessed at least some stocks. Once again, there was more wealth in the City than in the Middlesex part of the parish.10 The fact that 7.5 per cent of the householders were deemed "substantial" according to the Marriage Duty Tax (those with a personal estate of not less than £600 or real estate worth not less than £50 per year, titled persons, and those with a professional qualification) indicates the presence of a small middle and upper class.11

Although surviving tax returns from the eighteenth century provide far less detail, it is clear that overall levels of wealth in the parish and their distribution did not change substantially. The returns to a government enquiry about the ability of householders to pay assessed property taxes in 1798 demonstrate that the majority of the parish continued to be economically deprived, with 61 per cent of households in East Smithfield and 47 per cent in Portsoken reported as being not liable for any taxes. Those able to pay taxes were divided into five groups according to the amount of tax paid, and 55 per cent of those in East Smithfield, and 21 per cent in Portsoken, fell into the lowest two groups. 39 per cent of the shopkeepers assessed in East Smithfield had difficulty paying their taxes.12

Whereas in the late seventeenth century high levels of poverty in the parish were accompanied by a minority of very wealthy households, a century later, particularly in the Middlesex part of the parish, the small elite of the parish were more likely to be middle than upper class. Although the categories are not strictly comparable, it is revealing that whereas 7.5 per cent of householders were deemed "substantial" in 1695, in East Smithfield in 1798 only 5.6 per cent of householders paid the highest levels of tax. In 1813, 6.6 per cent of parish occupations were middle or upper class, including only 1.2 per cent labelled as gentlemen.13

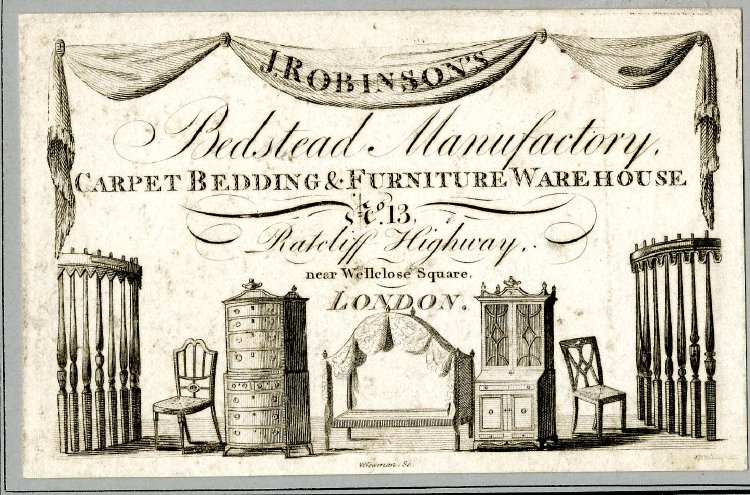

Trade card of J Robinson's Bedstead Manufactory at No. 13 Ratcliff Highway, near Wellclose Square, London, c.1770. British Museum, Trade cards Heal 28.195. © Trustees of the British Musuem.

Trade card of J Robinson's Bedstead Manufactory at No. 13 Ratcliff Highway, near Wellclose Square, London, c.1770. British Museum, Trade cards Heal 28.195. © Trustees of the British Musuem.

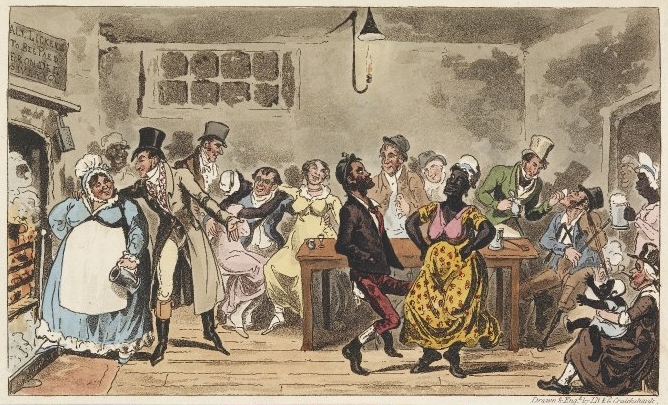

Economy

A large parish, St Botolph contained a wide range of occupations, with concentrations in food provisioning, warehousing, maritime trades, manufacturing, and clothmaking. As befitted a part of London immediately outside the walls but close to its markets, the City part of the parish had slaughterhouses, butchers' shops, brewers and distillers. Since Whitechapel Road was one of the principal roads out of the City towards the east, there were also a number of inns for travellers. City merchants and the East India Company maintained warehouses in this area. There was also a considerable amount of craftwork in the parish, including woodworking, metalwork and textile manufacture, and there were a number of shops selling clothing. The Middlesex portion of the parish, next to the river, contained trades servicing shipping, including the Victualling Office and King's Brewhouse for supplying the Royal Navy, as well as other brewshops and tallow chandlers. A large number of porters and sailors lived in the parish. According to a listing of occupations for 1813, 15.3 per cent were in unskilled trades, 27.5 per cent in semi-skilled, 13.7 per cent in skilled, and 12.3 per cent in the provisioning trade.14 Perhaps owing to the absence or mortality of sailors, a relatively high proportion of households in the parish (20 per cent in 1666) were headed by women, who often worked in the silk-throwing and victualling trades or ran lodging houses.15

Housing

The parish escaped the Great Fire of London and therefore much of the housing was old and in increasingly poor condition. In typical early modern fashion, the best buildings were on the main streets and probably constructed in brick, while small lanes and alleys off the streets, often developed as infill during the period of rapid growth in the seventeenth century, were full of poorly built wooden structures. In his Survey of London (1720), John Strype described the buildings as a mixture of well built and "very handsome" buildings, alongside "ordinary", "indifferent", and "small and mean" buildings. Perhaps the worst place in the parish was Maidenhead Alley, which he described as "small, nasty and beggarly".16

According to the 1694 Marriage Duty Tax, housing in Tower precinct was in relatively small, low-quality buildings with a single room on each storey.17 In the Middlesex portion of the parish much of the housing, particularly in the alleys off East Smithfield, was densely packed and even smaller in scale, consisting of two storeys or less, covering an area of about two hundred square feet, and built out of timber. These houses were inhabited by single families, though some were used for industry.18 In the eighteenth century many of the rented rooms were furnished, reflecting the poor and transient nature of the inhabitants.

Poor Relief and Charities

As seen with the distribution of wealth, a high proportion of inhabitants in the parish were poor. During the plague in 1665, St Botolph experienced severe crisis mortality (with 6.9 times as many deaths in 1665 as the average for the previous decade), and members of two out of every three households in the parish died.19

George Cruickshank, AllMax in the East, depicting the interior of the Coach and Horses public house, Nightingale Lane, East Smithfield, 1821 British Museum, Reid 102, British Satires 14341. © Trustees of the British Museum.

George Cruickshank, AllMax in the East, depicting the interior of the Coach and Horses public house, Nightingale Lane, East Smithfield, 1821 British Museum, Reid 102, British Satires 14341. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Assistance for the poor came from a complicated mixture of official and voluntary sources. Parochial relief took the usual form of a combination of pensions and casual payments, and amounted to £2,471 in 1739. Reflecting the distribution of the poor, more money (£1,311) was spent in the Middlesex portion of the parish, despite the fact it had a smaller population. In 1705, the parish reported that it spent considerably more on relief than it collected from the rates, and it sought extra relief from the richer parishes in the City.20 By at least 1734 the City part of the parish had a workhouse near the Minories in Seven Step Alley close to Gravel Lane, and in 1736 a further workhouse was built in Nightingale Lane to serve the Middlesex half of the parish. These institutions came to house a significant proportion of those dependent on relief from the parish for long periods: according to 1776 Parliamentary Returns, the City workhouse could house 200 paupers, and the Middlesex house a further 250. Others paupers, particularly the disorderly or the insane, were housed and put to work at large pauper farms run by contractors on the outskirts of the metropolis, such as Mr Overton's and Mr Deacon's at Mile End, and Sarah Stowell's on Bear Lane in Southwark.21

The substantial relief provided by the parish was supplemented by a significant number of endowed charities, many of which dated from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. These included:

- in 1547, Anne Wethers left £230 to establish a small hospital and left five tenements for poor almswomen with a stipend of six pence a week.

- in 1563 Dame Anne Packington left endowments to fund £7 13s 4d per year for the care of the poor of the parish, and £3 per year for the education of poor children.

- in the 1590s, the Merchant Taylors' Company built almshouses on Tower Hill for poor women.

- in 1605 John Conyers left £100 in trust for yearly payments to the poor of the parish and an estimated £40 for clothing the poor.

- in 1606 George Clarke left £293 6s 8d for the relief of poor families in the parish.

- in 1610, Robert Dow left an endowment of £3,500 for charity, initially for poor widows and old needy maidens.

- in 1624, Christopher Tamworth endowed £400 for support of ten poor men and women in the parish.

- in 1631, Henry Fryer endowed £2,000 for the relief of poor families in St Botolph and two other parishes, worth £100 per year. An additional stipend of £10 annually was settled on twenty poor widows.

- in 1657, Elizabeth Viscountess Lumley established an almshouse with twelve rooms for the reception of six almspeople from St Botolph Aldgate and six from St Botolph Bishopsgate with annual stipend of £6 13s 4d. Evidence of how this money was spent, including the names of some female recipients of this charity, can be found in the parish Miscellaneous Account Books (AO).

Some of these benefactions were specifically targetted at either the City or Middlesex portions of the parish.22

In 1714, in his book Pietas Londinensis, James Paterson observed that the parish was particularly well served by voluntary donations, being

During the eighteenth century the pace of donations for the parish poor slowed, as charitable donations in the metropolis shifted to associational charities such as the Foundling Hospital. But they did not disappear:

- in 1730, Thomas Bray left money to purchase "suits of mean but new apparel of mantuas and petticoats" for the use "of the poor women of both parts of the parish ... who are observed to come most frequently to church on the Lord's day and weekdays so that they may be decently clothed and not afraid to come".24

- in 1728, Ann Neptune left £20 per year to the poor of the Middlesex part of the parish.

- in 1777, Hugh Humstone left £7,000 to support blind persons in the Middlesex part of the parish.

It is likely that these established charities were supplemented by frequent individual handouts from charitably inclined parishioners, but this raised concerns about begging in the parish. In 1735 the combined vestry complained that "the inhabitants were greatly obstructed and annoyed in going out of the church after sermon on Sunday, by the passages being crowded with beggars".25

Poor parishioners also benefitted from charity schools. One was founded in 1673 by Sir Samuel Starling, which initially provided education for sixteen "poor boys".26 This was later expanded to accommodate forty boys and thirty girls. In 1689 another school, supported by voluntary contributions and a substantial donation from Sir John Cass, was founded for the purpose of clothing and educating poor children of the ward; it eventually accommodated fifty boys and forty girls. Following their training, the boys were to be put out as apprentices and the girls as domestic servants.27 In 1775 John Lemborough left £300 in aid of charity schools in both parts of the parish.

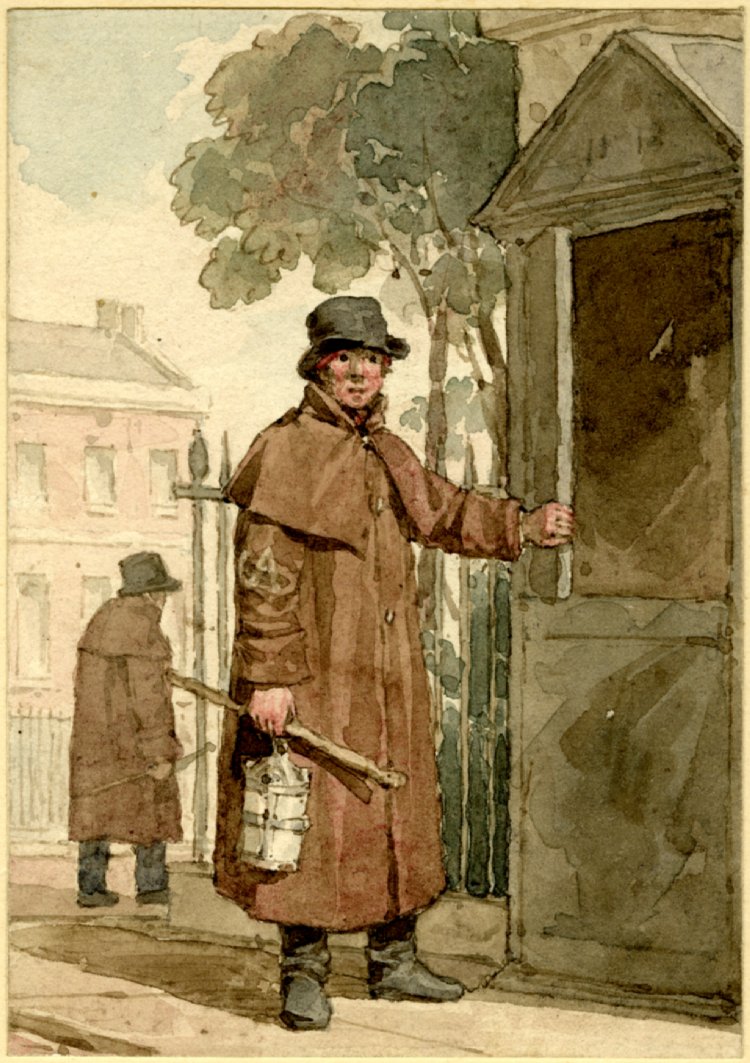

John Augustus Atkinson, The Watchman, n.d. early nineteenth century. British Museum, British Roy PV. © Trustees of the British Museum.

John Augustus Atkinson, The Watchman, n.d. early nineteenth century. British Museum, British Roy PV. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Crime and Policing

High levels of poverty in the parish were not reflected in high prosecution rates for crime, though whether this was because few crimes took place, or because victims chose not to prosecute, is impossible to determine. Between 1604 and 1658 there were only eighteen arrests by ward officers in Portsoken Ward recorded in the Bridewell records, an average of one every three years, compared to hundreds if not thousands over the same period from other wards in the City.28 This pattern continued into the late seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, when there were relatively few commitments to the Middlesex house of correction from St Botolph, and few prosecutions taken to the Middlesex Sessions. In particular, and despite Bray's support for the reformation of manners campaign, compared to other parts of the metropolis there were few prosecutions for victimless offences such as vice.29 Prosecutions of other crimes were also relatively rare. In 1740, only twenty indictments for misdemeanours and felonies at the Middlesex Sessions emanated from St Botolph's, amounting to one indictment for every 509 inhabitants.30 Over the entire 1690-1800 period 665 accounts of trials at the Old Bailey include the word "Aldgate", or an average of six per year, amounting to one trial per year for every 2,300 residents.

Crime was, however, occasionally a matter of concern in the parish. Between 1721 and 1725 the number of indictments at the Old Bailey averaged sixteen per year, 88 per cent of which were for theft, particularly from houses. In 1779, there were complaints about an outbreak of housebreaking "committed by a villainous gang who reside in Gravel Lane" near Houndsditch.31

The paucity of criminal prosecutions could be explained by the fact that victims of crime were disinclined to report them. They may have been dissuaded by the cost of prosecutions, given the poverty of many inhabitants, and by the relatively long distance (compared to the rest of the metropolis) needed to travel from the parish on the eastern boundary of the City to the prisons and courts of justice in the western half of the metropolis. In 1707 a group of constables and other officers from the East End sought permission from the Middlesex Justices to punish petty offenders in nearby Whitechapel Prison in order to save them the trouble of carrying prisoners to Bridewell or New Prison, but the petition was rejected.32

Alternatively, the low prosecution rates could paradoxically be due to low levels of policing in the parish, which resulted in fewer arrests, particularly for victimless offences. In 1663 Portsoken Ward had five constables, or one for every 277 houses, the third lowest provision in the City wards. More than a hundred years later the number of constables had increased to six, or one for every 231 houses, the second lowest provision of the City's twenty-six wards. In the early eighteenth century the ward had one watchman for every 260 inhabitants. In 1737, when it was allocated twenty-eight watchmen, this worked out as one for every 49.5 houses in the parish. Only one other ward in the City was less well provided for.33 In the Middlesex part of the parish the twenty-three watchmen in 1822 provided a similarly low level of cover, though at this date this was supplemented by four men as "evening patrol" and four as "night patrol".34

A further possibility is that the relative social stability of the parish may have led inhabitants to settle their disputes informally, without recourse to legal action. Many of the cases which were prosecuted at the Middlesex Sessions concerned defamation, which suggests that community based discipline, in the form of public censure, may have been used to maintain order. There is also evidence that so-called trading justices were active in the area, mediating disputes informally without recourse to the courts. Only 10 per cent of constables in Portsoken Ward in 1728-31 were deputies rather than the householders who were nominated to serve, compared to up to 90 per cent in some of the wealthier wards in the City.35 Those who acted as constables in the parish were predominantly householders, who as figures of authority in the community may have been able to broker informal settlements to criminal accusations.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keywords St Botolph:

Documents Included on this Website

- Apprenticeship Indentures and Disciplinary Cases (IA)

- Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor Account Books (AC)

- Lists of Paupers Receiving Parish Relief (LP)

- Minute Books of Parish Vestry Sub-Committees (MO)

- Minutes of Parish Vestries (MV)

- Miscellaneous Parish Account Books (AO)

- Pauper Settlement, Vagrancy and Bastardy Examinations (EP)

- Register of Paupers Admitted to the Workhouse (RW)

- Registers of Pauper and Bridewell Apprentices (RA)

- Registers of Poor Children under Fourteen years in Parish Care (RC)

- Regular Parish Payments to Paupers (AP)

Introductory Reading

- Merry, Mark and Baker, Philip. "For the house her self and one servant": Family and Household in Later Seventeenth-Century London. The London Journal, 34, 3 (Nov. 2009), pp. 205-233.

- Power, M. J. The East and West in Early-Modern London. In Ives, E.W. et al, eds, Wealth and Power in Tudor England: Essays Presented to S.T. Bindoff. 1978, pp. 167-185.

- Power, M. J. East London Housing in the Seventeenth Century. In Clark, Peter and Slack, Paul, eds, Crisis and Order in English Towns. 1972, pp. 237-62.

- Spence, Craig. London in the 1690s: A Social Atlas. 2000.

- Thompson, H P. Thomas Bray. 1954.

Online Resources

- Histpop - The Online Historical Population Reports Website

- Life in the Suburbs: Health, Domesticity and Status in Early Modern London

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 William Maitland, The History and Survey of London from its Foundations to the Present Time, 2 vols (1760), II, p. 1081. ⇑

2 Leonard D. Schwarz, Conditions of Life and Work in London, c. 1770-1820, with Sepcial Reference to East London (Oxford PhD, 1976), p. 220. ⇑

3 H. P. Thompson, Thomas Bray (1954); Leonard W. Cowie, Bray, Thomas (bap. 1658, d. 1730); Laird Okie, Kennett, White (1660-1728), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, consulted 27 April 2010. ⇑

4 P. E. Jones and A.V. Judges, London Population in the late Seventeenth Century, Economic History Review, 6 (1935-6), p. 62; M. Dorothy George, London Life in the Eighteenth Century (1925, 1965), pp. 408-09. ⇑

5 William Maitland, The History of London, from its Foundation by the Romans to the Present Time (1739), p. 391. ⇑

6 Mark Merry and Philip Baker, "For the house her self and one servant": Family and Household in Later Seventeenth-Century London, London Journal, 34, 3 (2009), pp. 205-233. ⇑

7 Schwarz estimates that there was an average increase of one child per family between 1770 and 1790: Conditions of Life and Work in London, p. 333. ⇑

8 1690s and 1801 data kindly supplied by James Alexander. ⇑

9 Justin Champion, London’s Dreaded Visitation: The Social Geography of the Great Plague in 1665 (1995), pp. 15, 72. ⇑

10 Craig Spence, London in the 1690s: A Social Atlas (2000). ⇑

11 P.E. Jones and A.V. Judges London Population in the late Seventeenth Century, Economic History Review, 6 (1935-6), p.62. ⇑

12 Schwarz, Conditions of Life and Work in London, pp. 221, 345. ⇑

13 Schwarz, Conditions of Life and Work in London, p. 227. ⇑

14 Schwarz, Conditions of Life and Work in London, p. 227. ⇑

15 Derek Keene, The Poor and Their Neighbours: The London Parish of St Botolph outside Aldgate in the 16th and 17th Centuries (Unpublished paper, Centre for Metropolitan History, n.d.), p. 15. ⇑

16 John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, 2 vols (1720), volume 1, book 2, chapter 2, pp. 27-28. ⇑

17 Merry and Baker, Family and Household in Later Seventeenth-century London, pp. 211-12. ⇑

18 M. J. Power, East London Housing in the Seventeenth Century, in Peter Clark and Paul Slack, eds, Crisis and Order in English Towns (1972), pp. 237-62. ⇑

19 Champion, London’s Dreaded Visitation, pp. 48-51. ⇑

20 Ronald W. Herlan, Social Articulation and the Configuration of Parochial Poverty in London on the Eve of the Restoration, Guildhall Studies in London History, 11 (1976), p. 47, n. 21. ⇑

21 Guildhall Library, MS 2642-43, cited by Pam Cross, The Operation of the Workhouse in the Parish of St Botolph Aldgate, c. 1734-1834 (BA dissertation, Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, 1990), p. 40. ⇑

22 W. K. Jordan, The Charities of London 1480-1660 (1960), pp. 96, 106, 113, 126, 140, 164, 384. ⇑

23 James Paterson, Pietas Londinensis: or, the Present Ecclesiastical State of London (1714), pp.48-51. ⇑

24 From his will, cited by Thompson, Thomas Bray, p. 88. ⇑

25 GL MS 2644-1, cited by Cross, The Operation of the Workhouse, p. 4. ⇑

26 Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, Book 2, Chapter 2, pp. 25-26. ⇑

27 A New and Compleat Survey of London, 2 vols (1742), II, p. 694; Arthur G. B. Atkinson, St Botolph Aldgate: The Story of a City parish (1898). ⇑

28 Paul Griffiths, Lost Londons: Change, Crime and Control in the Capital City 1550-1660 (Cambridge, 2008), Map 2, p. 444. ⇑

29 Robert B. Shoemaker, Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex (Cambridge, 1991), pp. 300-07. ⇑

30 Peter Linebaugh, Tyburn: A Study of Crime and the Labouring Poor in London During the First Half of the Eighteenth Century (Warwick University PhD, 1975), p. 60. ⇑

31 Andrew T. Harris, Policing the City: Crime and Legal Authority in London, 1780-1840 (Columbus, Ohio, 2004), pp. 34-35. ⇑

32 London Metropolitan Archives, MJ/SP Oct 1707, #31. ⇑

33 J. M. Beattie, Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror (Oxford, 2001), pp. 116, 195; Drew D. Gray, Crime, Prosecution and Social Relations: The Summary Courts of the City of London in the Late Eighteenth Century (Basingstoke, 2009), p. 61. ⇑

34 Leon Radzinowicz, A History of English Criminal Law, 5 vols (London and Oxford, 1948-90), II, p. 501. ⇑

35 Beattie, Policing and Punishment , p.148. ⇑