The Courts

The Deaf Judge, or Mutual Misunderstanding. 1796. Lewis Walpole Library, 796.9.10.3. © Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

The Deaf Judge, or Mutual Misunderstanding. 1796. Lewis Walpole Library, 796.9.10.3. © Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Introduction

Criminal accusations were heard in a number of different ways, depending on the nature of the offence and the wishes of the prosecutor and magistrate who heard the initial accusation. The complaint could be adjudicated informally by a Justice of the Peace, it could result in a summary conviction without trial, the accused could be bound over to attend a sessions of the peace, or they could be formally indicted and tried by a jury. Those trials took place at a sessions of the peace or the Old Bailey.

Sessions of the Peace

Under their commissions of the peace and oyer and terminer, Justices of the Peace meeting in sessions had the power to try both misdemeanour (petty) and serious offences, but most felony cases (the most serious offences, which at least at some time in the past had been punishable by death) were tried under the separate commission of gaol delivery at the Old Bailey. There was some discretion in deciding whether felonies were tried at sessions or the Old Bailey, but in practice in London most were tried at the latter. Some serious misdemeanours, such as attempted rape and attempted sodomy, were also tried at the Old Bailey. Petty theft, the theft of goods worth less than a shilling, was prosecuted at both sessions and the Old Bailey.

Reflecting the fluid boundary between criminal offences and the regulation of nuisances and public spaces at this time, a wide range of petty offences were tried at sessions. The most common were offences against the peace (assault, riot), property offences (petty theft, receiving stolen goods, fraud, trespassing), disorderly houses (keeping an alehouse without a licence, keeping a disorderly alehouse, keeping gaming houses and brothels), and regulatory offences (failure to serve on the night watch, failure to repair the highway or keep ditches scoured).

At their sessions, the Justices heard the cases of all those bound over by recognizance (most were discharged without further action), while indictments were tried by juries. Grand juries decided which indictments had sufficient evidence to go to trial, labelling these "true bills" and those they rejected "ignoramus". The "true bills" were tried by a petty jury. See The Criminal Trial.

There were separate sessions for the City of London (which met eight times a year), Middlesex (which also met eight times a year), and Westminster (which met four times a year, though many cases arising in Westminster were also tried at the Middlesex sessions). Cases deriving from Southwark (on the south side of the Thames) were tried either at a separate borough sessions or at the Surrey quarter sessions.

Although primarily a criminal court, the sessions also dealt with a wide range of business, including poor relief, apprenticeships, regulating nuisances, and repairing highways and bridges. For documentary evidence of their work, see Middlesex Sessions Records.

Old Bailey

Unlike the rest of the kingdom, there were was no assizes court for trials of felonies in the metropolis. Instead, most serious crimes arising from the City of London and Middlesex were heard by trial juries at a court of gaol delivery held at the Old Bailey, though those from south of the river were tried at the Surrey assizes. Unlike in other counties where the two courts met at different times, the sessions of the peace for the City and Middlesex were held immediately before the sessions at the Old Bailey, thereby allowing the same grand juries to sit for both the sessions and the Old Bailey, and for serious cases to be referred to the higher court. Consequently in both the City and Middlesex the records of the sessions and Old Bailey were kept together, as is evident in the Sessions Papers (PS) before 1755. Although those accused of felonies in Middlesex were initially kept in New Prison, before their trials they were transferred to Newgate prison, where accused felons from the City were kept. Conveniently, Newgate was located directly next door to the Old Bailey.

Whereas Justice of the Peace heard cases at sessions, trials at the Old Bailey were predominantly conducted by judges from the high courts at Westminster and the principal officers of the City of London (the Lord Mayor and the Recorder). Although they rarely conducted trials, other City magistrates were also included in the commission. Most Justices of the Peace for Middlesex, however, were not, and they were not even allowed to sit on the judicial bench, despite the fact that the vast majority of the cases tried at the Old Bailey came from Middlesex. Although this reduced the formal role played by the Middlesex Justices in trials for serious crime, some played an important and innovative role in the pre-trial process.

For more information on trials at the Old Bailey, including searchable access to the printed trial accounts, see the Old Bailey Proceedings Online. These accounts are also included on this website, along with the manuscript Sessions Papers (PS), which include depositions and examinations of witnesses and the accused prepared before trial. The actual legal records of trials at the Old Bailey are kept in the London Metropolitan Archives.

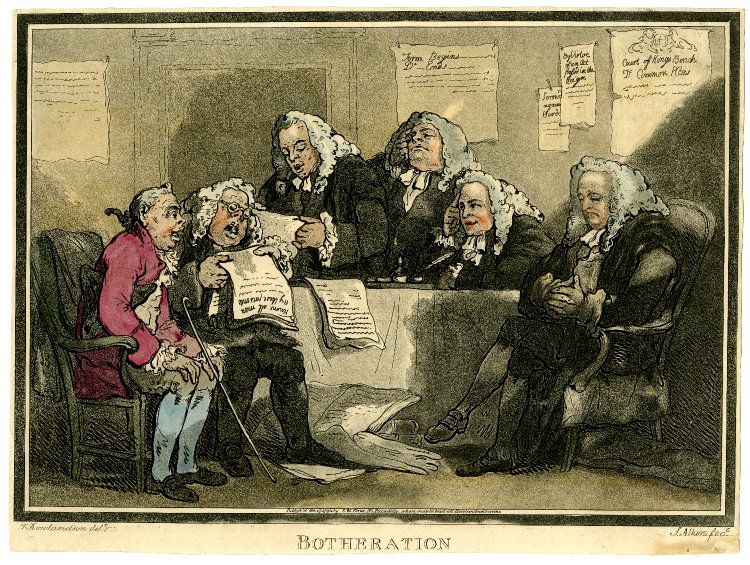

Thomas Rowlandson. Botheration. 1793. British Museum, Satires 8393. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Thomas Rowlandson. Botheration. 1793. British Museum, Satires 8393. © Trustees of the British Museum.

King's Bench

As one of the high courts of Westminster, King's Bench (crown side) heard misdemeanour cases by exercising their supervisory role (using the writ of certiorari) from all over the country. But because the court sat in Middlesex, it could also hear initial prosecutions for misdemeanours arising from the county (but not the City of London), and a substantial number of cases of assault, riot, highway offences and the keeping of disorderly houses were tried there. Although prosecuting a case at King's Bench was more expensive, there were several potential advantages for prosecutors over taking their case to sessions: the higher cost of defending such cases may have forced defendants to reach an informal settlement, the punishments for those convicted were more severe, convicted defendants may have had to pay costs and damages to their prosecutors, and the cases received more publicity than at sessions. The records of King's Bench are kept at The National Archives.

Church Courts and Civil Courts

Londoners could also prosecute, and be prosecuted, in other courts. With the boundary between crime and civil disputes fluid, the range of possible subjects of litigation in these courts was broad. The large number of courts in London, and their overlapping jurisdictions, facilitated vexatious litigation. For example, an assault arising out of a property dispute might be prosecuted in any one of a number of courts.

The Church Courts dealt with religious and morals offences. Weakened by the Act of Toleration of 1689, Church Court business was largely confined to defamation and matrimonial cases in the eighteenth century. Small scale property disputes (including those arising out of debts) were litigated in the London Mayor's Court, the Sherriff's Court, and Courts of Requests, while other cases went to the common law courts of Westminster, including Common Pleas and King's Bench (plea side), and the equity courts of Chancery and the Exchequer.

While readers may find references to them, no records from these courts have been included in London Lives.

Introductory Reading

- Beattie, J. M. Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror. Oxford, 2001.

- Dowdell, E. G. A Hundred Years of Quarter Sessions. Cambridge, 1932.

- Shoemaker, Robert B. Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex. Cambridge, 1991.

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography