Workhouses

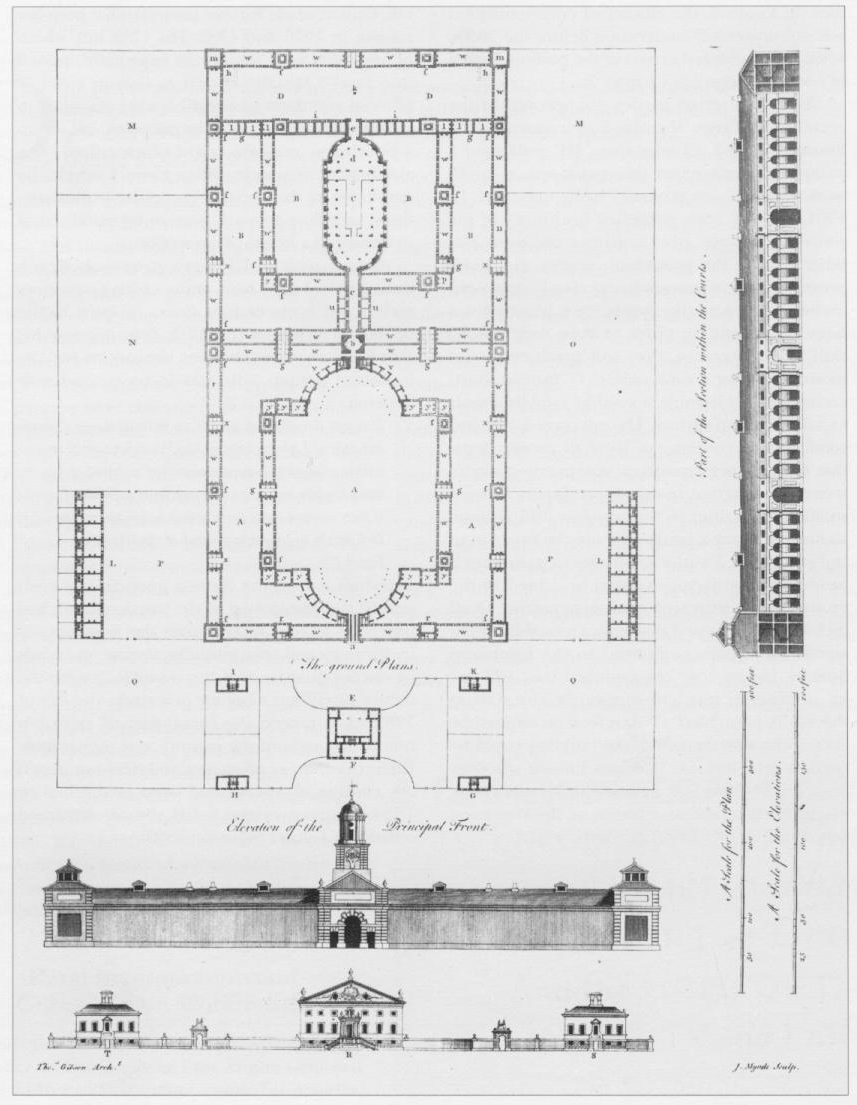

Thomas Gibson's plan for a workhouse as included in Henry Fielding, Proposal for Making Effectual Provision for the Poor, 1753. © London Lives.

Thomas Gibson's plan for a workhouse as included in Henry Fielding, Proposal for Making Effectual Provision for the Poor, 1753. © London Lives.

- Introduction

- The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

- The London Workhouse

- Workhouse Test Act and Account of Several Workhouses

- Parish Workhouses

- Workhouse Conditions

- Regimen and Diet

- London Workhouses in 1776-7

- Contractors, Private Workhouses and Baby Farms

- Henry Fielding's Plan

- Exemplary Lives

- Introductory Reading

- Online Resources

- Footnotes

Introduction

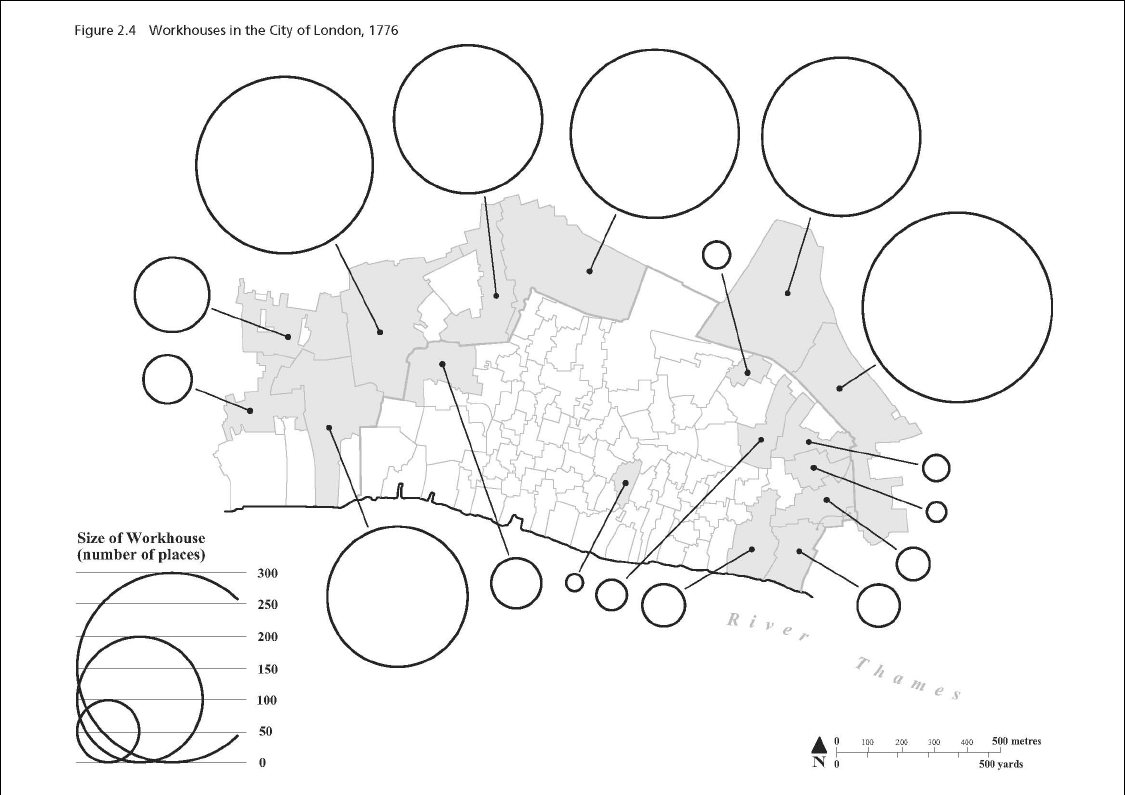

By 1776 over 16,000 individual men, women and children were housed in one of the eighty workhouses in metropolitan London; between 1 per cent and 2 per cent of the population of London. Workhouses, institutions in which the poor were housed, fed and set to work, had by this time become the most common form of relief available to Londoners.1 The process of creating this complex landscape of institutions, however, stretched over three centuries, and resulted in a variety of institutions that would have confounded the expectations of the men and women who established them.

The Sixteenth and Seventeenth Centuries

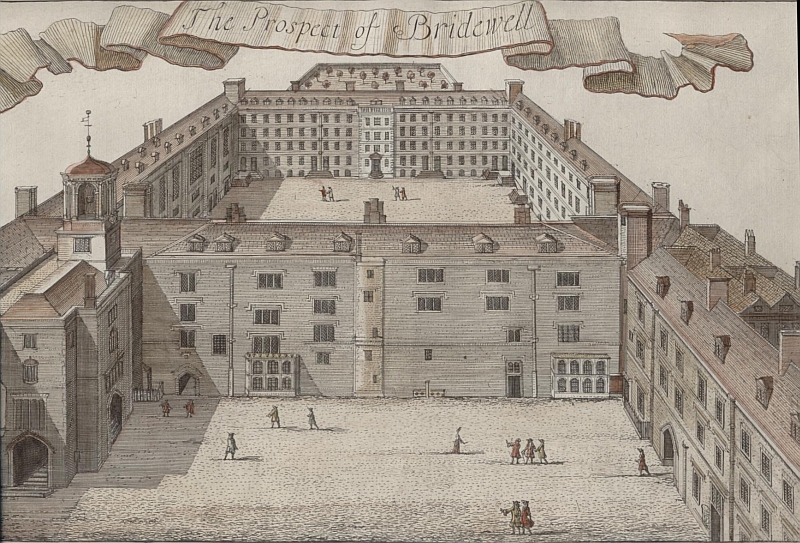

At regular intervals through the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, and especially following the establishment of the Royal Hospitals (and in particular Bridewell Hospital and Prison in 1553), Londoners attempted to create city-wide employment schemes or residential workhouses as a solution to the problem of poverty and economic dislocation. After Bridewell, which quickly evolved into the combination of a house of correction for the punishment of petty offenders and an industrial school, which it remained throughout the eighteenth century, London's next major experiment of this kind was Samuel Hartlib's Corporation of the Poor, established in 1648, which in turn built on the ideas of projectors such as Rowland Vaughn. Hartlib's experiment in collective employment, which at its most radical aspired to the creation of an egalitarian commonwealth of the poor, survived just a dozen years. By the time the foundation was given a firm legal footing as part of the Act of Settlement in 1662, it had already collapsed, though inclusion of the provisions for the Corporation in the Act itself effectively publicised the venture.2 The same legislation also empowered Middlesex and Southwark to establish their own corporations, and in 1664 Middlesex spent £5,000 creating a new workhouse at Clerkenwell, adjacent to the house of correction. Initially the workhouse provided raw materials for the adult poor to work up at home, and accommodation for the "reception and breeding up of poor fatherless and motherless infants".3

The Prospect of Bridewell from John Strype's, An Accurate Edition of Stow's Survey of London (1720). © Tim Hitchcock.

The Prospect of Bridewell from John Strype's, An Accurate Edition of Stow's Survey of London (1720). © Tim Hitchcock.

In 1676 Thomas Firmin established a parallel scheme in Aldersgate for employing the poor in the City of London, and through it provided training and a stock of flax for home working. This project survived through Firmin's death in 1697, and its existence provided one model for the later Corporation of the Poor or London Workhouse. Again using the workhouse half of the house of correction at Clerkenwell, in 1688 Sir Thomas Rowe created a College of Infants, which failed after just a few years, to be replaced by the Quaker Workhouse at Clerkenwell. This workhouse was based on the ideas of John Bellers and incorporated many of the commonwealth aspirations familiar from Samuel Hartlib's writing and from continental pietism.4

The aspiration to create a metropolitan, or at least City-wide institution, however, reached its apotheosis in the re-establishment of the Corporation of the Poor for London - also known as the London Workhouse - in 1698.

The London Workhouse

Throughout the 1690s pressure to reform the system of poor relief and the manners (morals) of the poor grew. The Societies for the Reformation of Manners, active from 1690, employed the criminal justice system to discipline the poor, but in parallel a wider national movement to create workhouses in major cities also evolved with the related aim to "inure the poor to labour", and train up poor children to a religious and industrious life. In London from 1688 Thomas Firmin and Sir Robert Clayton organized a voluntary house-to-house collection in aid of the poor, to which the new king, William III, gave both his support and money - donating initially £2,000 in 1688, and later £1,000 a year through the 1690s to what became known as the The King's Letter Fund. Between 1694 and 1705 Parliament also considered substantial reform of the poor relief system on at least thirteen separate occasions, a process that only lost impetus with the failure of Sir Humphrey Mackworth's attempt to re-codify the poor laws in 1705. During these same years the Board of Trade, under John Locke's leadership, spent much effort enquiring into the workings of the poor laws, and attempting, but largely failing, to generate a consistent reform agenda that had setting the poor to work at its core. In the absence of effective national reform, and following the lead of John Cary and the City of Bristol, thirteen Corporations of the Poor were established on the basis of local Acts of Parliament in all the major cites of England in the decade and a half after 1696. These institutions were generally run under the auspices of local city government, and took on the character of a combined house of correction and industrial school for children, and in relation to children at least, were intended largely to replace parochial provision.5

London was keen to follow the Bristol example, and hoped that specific provision for the creation of a Corporation covering the area within the Bills of Mortality would be included in national legislation promoted by the Board of Trade, but when this failed in 1697, the Lord Mayor, Sir Humphrey Edwin, recommended that the Interregnum Corporation of the Poor as authorised by the Act of Settlement simply be revived.

Bridewell and Bethlem Archives, Bridewell and Bethlem, Minutes of the Court of Governors, 1738-51, BCB-21 (Box C04/3), LL ref: BBBRMG202060517.

Bridewell and Bethlem Archives, Bridewell and Bethlem, Minutes of the Court of Governors, 1738-51, BCB-21 (Box C04/3), LL ref: BBBRMG202060517.

On this basis, the City of London initially sought to create a non-residential employment scheme, of the sort Thomas Firmin had been running for twenty years; and in the Autumn of 1698 committed over £5,000 to the project, which was up and running by the early months of 1699. Two undertakers were hired, and a six week course of training in spinning wool was run for parish children. The entirely unrealistic expectation was that "any willing industrious & capeable person may earn from two shillings to four shillings per weeke & some five or six shillings per weeke". Over 400 people, primarily children, were trained, but the scheme collapsed in the summer of 1699; and the City turned instead to a residential workhouse model, leasing a house in Half-Moon Alley, off Bishopsgate Street, in August 1699. For the next dozen years the London Workhouse maintained, employed and educated substantial numbers of parish children; and punished a slew of beggars and vagrants. The house was divided, like Bridewell, between a Keeper's Side (the house of correction) and a Steward's Side, which functioned as a residential workhouse and industrial school for poor children, which would take in parish children at a charge of 12 pence per week. In 1703 the annual report claimed that 427 children had been maintained in the preceding year, and 430 vagrants corrected. Two beadles were directly employed by the Corporation to apprehend beggars, and a bounty of a shilling per beggar or vagrant was offered for their apprehension. This was later restricted to beggars only, when the numbers of prostitutes and the disorderly grew too large.

The Corporation, however, rapidly encountered significant opposition from the parishes, which had traditionally cared for their own poor. In part this was a simple reflection of the high cost of maintaining an institutional provision. Between 1698 and 1713, a total expenditure of £34,644 was authorised in support of the Corporation, while the earnings from manufacturing proved largely illusory.

In response to these demands many parishes simply refused to collect the money assessed on them in support of the Corporation, and the conflict with the parishes (driven primarily by finance, but inflected with political divisions as well) dragged on through the 1700s. By 1708 several parishes were questioning the legal basis of the Corporation, and in that year a committee of the Court of Common Council was charged with finding some way of reducing the expenditure on the house. This committee failed to produce a clear recommendation, but in 1712, in response to a request for more funding, the Corporation was forced to change its by-laws, and drastically reduce its workhouse function. Although it survived into the nineteenth century, from 1713 it stopped taking in parish children, and restricted its educational role to boarding children sponsored by individual benefactors at a cost of £50 for City children, and £70 for children from elsewhere. From this date the London Workhouse survived almost exclusively as a house of correction.6

Workhouse Test Act and Account of Several Workhouses

As a part of the same flowering of debate on social welfare that contributed to the creation of the Corporations of the Poor, the Society for the Promotion of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) was established in 1698. During the next two decades the Society actively supported the creation of a large number of charity schools and working charity schools across the country, and most especially in London. It also acted as a clearing house for correspondence tying local activists into a national movement for reforming the poor, and as a publishing house, producing both pamphlet literature on religion and social policy, and a large number of short moralistic pamphlets designed for consumption by the labouring poor. Following the Jacobite uprising of 1715 and the Hanoverian succession, many of the schools promoted by the Society were suspected of inculcating Jacobite principles in their students; in response the Society shifted its efforts towards facilitating the establishment of parish workhouses.

The Account of Several Workhouses, 1725. © London Lives.

The Account of Several Workhouses, 1725. © London Lives.

The percentage of the SPCK's effort and time taken up with workhouses grew slowly between about 1719 and 1723. In 1720 the Society offered a premium to any town setting up a workhouse and gradually more and more of the Society's correspondents wrote to describe and commend local experiments. In 1722 the Society began to actively support Sir Edward Knatchbull and John Comyns in the drafting and passage of the Workhouse Test Act: "An Act for Amending the Laws relating to the Settlement, Imployment and Relief of the Poor".7 The Act itself was a hodge-podge of poor relief clauses with little obvious direction and few new ideas. But it gave legislative expression to a new kind of workhouse based on the idea of deterrence, rather than the belief that the poor's labour could be made profitable. The Act allowed parishes to refuse to relieve any applicant who refused to enter a workhouse. More than this, it gave a governmental stamp of approval to a series of institutions recently set up in the East Midlands and Essex.

With the passage of the Workhouse Test Act and in the same year the publication of Bernard De Mandeville's damning Essay on Charity and Charity Schools (1723), which argued that charity schools encouraged poor children to aspire above their station, the shift in emphasis from education in schools to industrial discipline in workhouses was complete. The publication by the SPCK of An Account of Several Workhouses in 1725, which gave details of the management and establishment of over forty-four workhouses and working charity schools, and noted the existence of a further seventy-seven institutions, effectively ensured that the provisions of the Workhouse Test Act would be adopted widely, indeed almost universally in the larger metropolitan parishes, in particular those of Westminster.8

Parish Workhouses

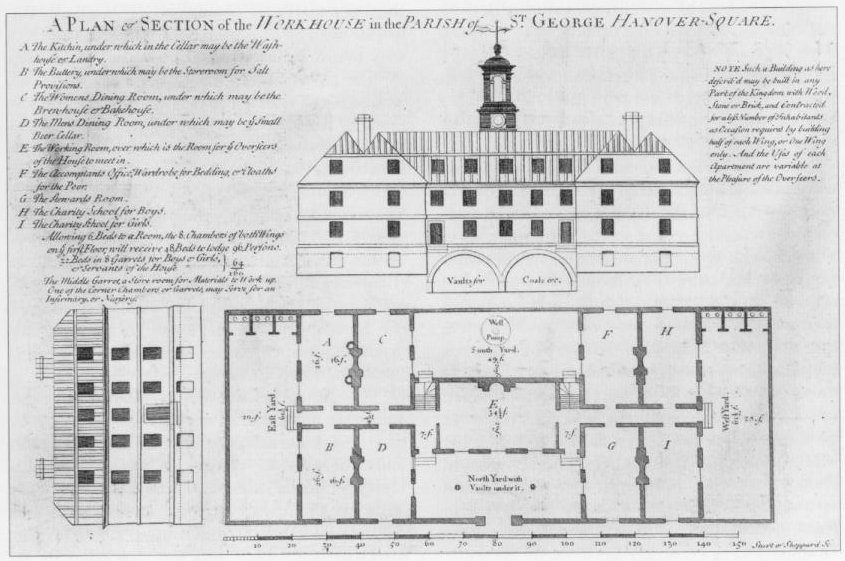

A Plan & Section of the Workhouse Belonging to St George Hanover Square, c.1724. © Trustees of the British Museum.

A Plan & Section of the Workhouse Belonging to St George Hanover Square, c.1724. © Trustees of the British Museum.

In metropolitan London the Workhouse Test Act provided the cue for the rapid expansion of parochial institutions. The earliest foundations were in the East End with Limehouse and Whitechapel establishing houses in 1724, followed St Katherine by the Tower in the following year and St Leonard Shoreditch in 1726. In 1725 in Westminster, St Martin in the Fields and St James both established substantial workhouses, accommodating several hundred paupers each; and in the following year St George Hanover Square and St Margaret followed their example. The house established by St George Hanover Square was built to a design commissioned by the SPCK from Nicholas Hawksmoor and was used as a model for many provincial houses. Over the course of the next few years most of the major urban parishes of metropolitan London created their own houses, with particularly large and important institutions being established by St Giles Cripplegate (1724), St Giles in the Fields (1725), St James Clerkenwell (1727), St Sepulchre, London Division (1727), St Andrew Holborn (1727), St Dunstan in the West (1728), St John the Evangelist (1728), and St Marylebone (1730).

In the City of London itself the majority of foundations took place in the 1730s, with a series of larger establishments concentrated in the parishes without the walls. These included houses in Christ Church Newgate Street (1729), St Dunstan in the East (1730), All Hallows Honey Lane (1731), St Andrew Undershaft (1733) and St Bartholomew the Great (1737).9

Most workhouses were established in the expectation that the adult, able bodied and male poor would form the majority of the workhouse population (or family as contemporaries termed it), the hope being that the labour of such paupers could be disciplined to help subsidize the cost of the house. But within just a few years of opening, these houses were almost universally forced to restrict or even abandon work undertaken by the inmates, and to refocus their efforts on the care of the ill, the orphaned and the elderly. Within months of the opening of the house belonging to St George Hanover Square a new infirmary was under construction. Similarly, at St Margaret Westminster, in 1727 six rooms were converted into a ward for the reception of the sick, as were six more in the following year. At St Martin in the Fields, one of the largest of London's parish workhouses, this refocussing was more drawn out, but by 1736 new and separate wards were being created for the sick, smallpox patients and lying-in women.10

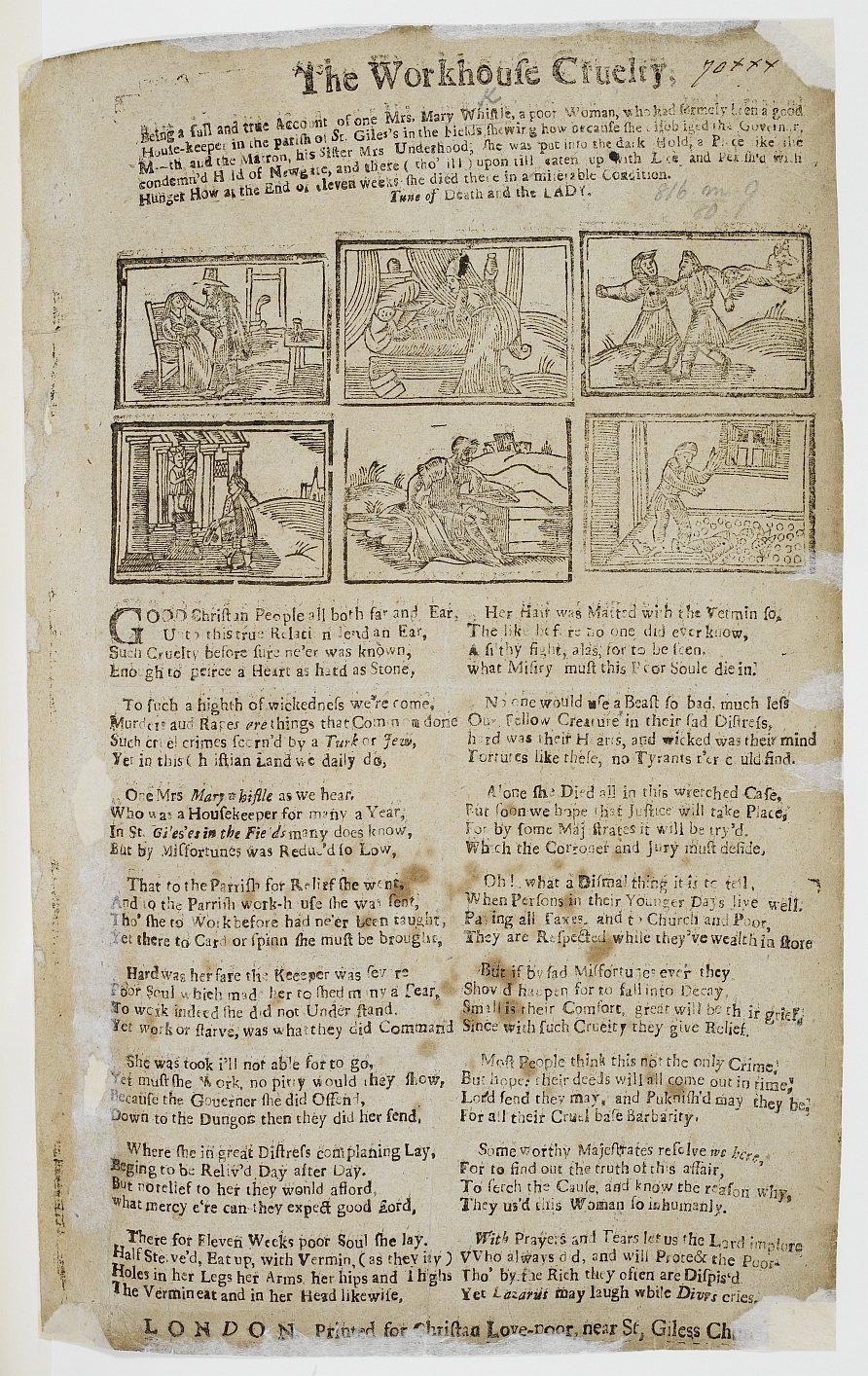

The Workhouse Cruelty, c.1731. © The British Libary.

The Workhouse Cruelty, c.1731. © The British Libary.

Typical of the population that came to occupy London's workhouses was that of St Luke Chelsea, the workhouse register for which is available through this site. This indicates that throughout the century the majority of inmates were women (50 per cent), and children (30 per cent); while adult male residents (19 per cent) were restricted to elderly inhabitants and the seriously ill.

The early form of these institutions was determined in part by the published information produced by the SPCK, especially its Account of Several Workhouses (1725, 2nd expanded edn 1732), but many were also set up and managed by Matthew Marryott, who worked closely with the Society, and who moved from Olney in Buckinghamshire, where he had been instrumental in establishing many early provincial houses, to London in 1724. From 1725 to 1727 Marryott practically monopolised the management of the larger houses established by the parishes of London, and either directly managed or sub-contracted the running of workhouses in St Giles in the Fields, St Leonard Shoreditch, St Martin in the Fields, St George Hanover Square and both St Margaret and St James, Westminster. But a series of complaints and workhouse scandals ensured that his monopoly was rapidly eroded. It was finally broken completely following the publication of a pamphlet and ballad detailing a number of deaths in the workhouse belonging to the parish of St Giles in the Fields between 1728 and 1731, and in particular that of Mary Whistle in 1731. As a result of this and other complaints Marryott was excluded from his role in managing several houses. He died in either late 1731 or early 1732.11

Workhouse Conditions

Unlike their nineteenth-century successors, eighteenth-century workhouses were not designed to be particularly unpleasant or punitive. And although they were initially set up with the adult, able-bodied (and generally male) poor in mind, they rapidly evolved to cater for young children and orphans, the elderly, and the ill. In size they could vary from a small parish house accommodating only twenty or thirty paupers, possibly managed by one of their own number, to massive bureaucratic institutions housing hundreds of people. The house belonging to St Martin in the Fields, whose register is included on this site, could accommodate 700 individuals in 1776. In most instances workhouses became general parish houses for the relief of the poor; while the larger institutions made available specialist accommodation for lying in and the provision of medical care, and for the elderly and infants and young children. Many houses also contained facilities to cope with accidents and emergencies (the parish shell or stretcher was usually stored at the workhouse), acted as parish mortuaries, and served as the venue for parish meetings and administration. For most parishes the workhouse represented the first and most important parish building after the church itself; and as such came to serve as the focus for many parish activities beyond poor relief.12

Typical of the larger London houses was that established by St James Westminster. The building used for the workhouse was purpose-built in 1726, and was described five years later as a "spacious brickhouse". It was built in the burial ground belonging to the parish and in the early 1730s could hold approximately 300 people, divided among "8 Wards, viz. 4 for women, 2 for men, 1 for boys, and 1 for girls, containing 18 beds in each ward". There was also a "ward for lying-in women, into which many are brought out of the streets to be delivered [and] another ward for an infirmary".

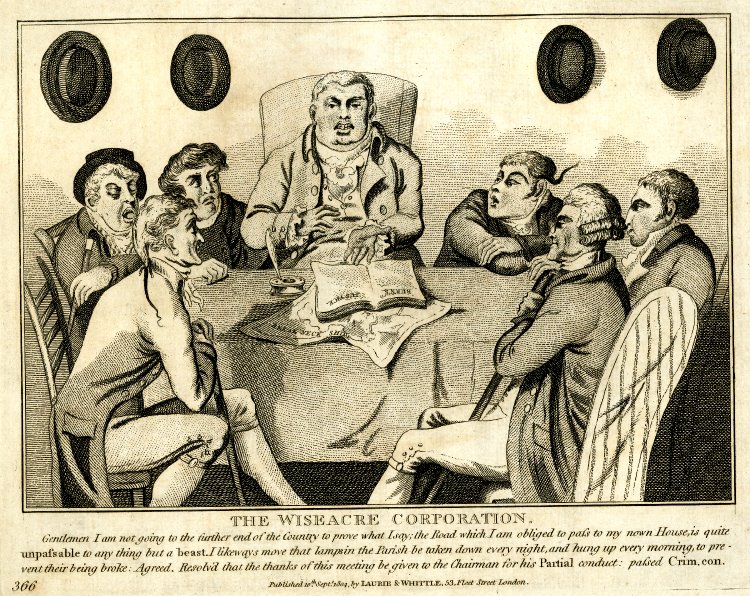

The Wise Acre Corporation, 1804. British Museum Satires 10358. © Trustees of the British Museum.

The Wise Acre Corporation, 1804. British Museum Satires 10358. © Trustees of the British Museum.

There were fourteen members of staff, each receiving wages of between £5 and £40 per year, plus board. Besides the master (Matthew Marryott from 1727 to 1729), who was paid £40 per annum, there was also a clerk, matron, assistant matron, laundry maid, porter, schoolmistress, matron of the infirmary and general maid servant. The highest paid of these posts was that of clerk, who earned a salary of £20 a year. The employees of the house were "allowed a convenient joint of meat every day for their dinners" and dined "immediately after the rest of the family". Their responsibilities were strictly divided between several spheres of activity. The porter, for instance, had responsibility for only three things. He ensured that all the men rose at the appointed hour in the morning, that meal times were indicated by the ringing of a bell, and that no one entered or left the house without the permission of the master. Similarly, the bread cutter was responsible for allocating "all the allowances of bread and cheese" and "such quantities of beer and coals every day ... as the governor shall direct".

Beyond these paid servants there were also numerous positions filled by the poor themselves. Each ward was looked after by a nurse recruited from among the poor, who was ordered to "thoroughly clean their respective wards and air the rooms if the weather permits"; "every morning sweep the passages and stairs leading from the floors of the respective wards, and on every Wednesday and Saturday scour the said passages and stairs and make clean the wainscot and balusters belong to the same". The nurses were also required "every morning immediately after prayers [to] make the beds and at other times of the day mend the bedding clothes and linen, and take care of them and all other things belonging to the persons under the particular charge". They looked after the sick, fetched their meals for them and notified the master or apothecary of any assistance that might be required, and for children between the ages of four and six, were expected to "dress, wash and comb them every morning and bring them clean to morning prayers, take care of them at their meals and at night ... [and] put them to bed". For these services the nurses received no wages or special allowances, but the vestry did promise to reward "'extraordinary diligence" with a small gratuity.

Below this large management structure were the inmates, who were employed by the work master, looked after in the infirmary, or delivered in the lying-in ward. Their days were regimented and controlled by both the paid and pauper staff. Every morning they were awoken by the ringing of a bell by the porter of the house, at seven in the winter and six in the summer months. Forty-five minutes was then allowed for the inmates to get up, and wash and dress themselves, before they had to be in the main hall of the workhouse for prayers read by the master. The only persons allowed to absent themselves from prayers were children under four and the bedridden. Having read prayers the master then counted the poor in the hall, taking note of their condition - whether children, aged, or infirm - while the mistress went to the various wards to list those unable to attend. The poor were then divided into messes for the purpose of determining the amount of food necessary for the day. Once this account had been taken the poor were dismissed into the hands of the work master and mistress, or, if children between the ages of four and six, sent to the schoolmistress for instruction. Other inmates were appointed to work in the laundry, while the nurses were sent back to the wards to make the beds and clean out the rooms.

Regimen and Diet

Every morning the work master and mistress assigned "every poor person a reasonable task to perform for a day's work in proportion to the party's ability ... [or] join[ed] two or three or four in a piece of work as shall be most convenient". Under the eye of the work master and mistress the poor then started their labour, children over the age of six being sent for short periods throughout the day to the schoolmistress to be taught to read.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 1776-87, B1072, LL ref: WCCDMV362040294.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 1776-87, B1072, LL ref: WCCDMV362040294.

At nine in the summer and as soon as possible after prayers in the winter, breakfast was served. A bell was rung by the porter to summon the inmates, and the men and boys over six then proceeded to the "men's hall" where they were "regularly placed at tables". Likewise, the women, and girls and children under six, went to the "women's hall", where they were "served with their messes in a decent manner". The master was present throughout the meal, and saw to it that everyone was there and maintained good order: anyone absenting themself without permission was denied one meal on the first occasion. Half an hour was allowed for breakfast, which conformed to one of three menus depending on the day of the week. On Sunday each person above six years old received five ounces of bread and a pint of beer; on Monday, Wednesday and Friday, a pint of beef broth and two and a half ounces of bread; and on Tuesday, Thursday and Saturday, a pint of mild porridge and two and a half ounces of bread. While breakfast was in progress the mistress toured the house seeing to it that bedridden inmates received their meals and were attended to by the nurses.

After breakfast everyone returned to work until, at one in the afternoon, the dinner bell was rung. Once again the poor trooped into the halls and a meal was served under the auspices of the master. Slightly more varied than breakfast, this was the main meal of the day. On Sundays, Tuesdays and Thursdays, the poor were served ten ounces of boiled beef, five ounces of bread and one pint of beer. On Mondays each adult received a pint of peas pudding; on Wednesday, a pint of rice milk, on Fridays, a pint of frumenty; and on Saturdays a pound of plum pudding and a pint of beer. An hour was allowed for dinner, after which the poor went back to work until at least six during the winter months and until supper was served at seven during the summer. During the winter an hour was allowed between the end of the working day and supper, during which time the inmates were left to their own devices.

Supper was the least substantial and most monotonous meal of the day. On Sundays each pauper received five ounces of bread, two ounces of cheese and a pint of beer, and during the rest of the week, four ounces of bread, one and a half ounces of cheese and half a pint of beer. No particular time limit was set on the evening meal, though it had to be finished by approximately half past eight, when the master read evening prayers, sending the inmates to bed at nine o'clock.

The unvaried routine described above was put into effect on five days a week. On Saturdays the poor were allowed to cease work at five in the afternoon during the summer and three in winter. On Sundays work was largely replaced by religious devotions. After breakfast on Sundays it was the master's duty to see that "the officers of the workhouse and likewise the poor not being dissenters from the church do attend constantly and reverently on divine service". After the morning service the master was allowed to "suffer those who desire it to go abroad" as long as no one was discovered using this time and freedom in begging or in becoming "disordered in liquor". The poor had to return to the house by half past eight in the evening, and were liable to lose their right to go abroad on Sundays for up to three months for any breach of the master's standards of behaviour. Eight days a year were reserved as holidays. "Good Fridays, Christmas Day and the two next days after it and the Monday and Tuesday in Easter and Whitsun week" were set aside from the constant round of work and meals.

The workroom at St James's workhouse, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

The workroom at St James's workhouse, from The Microcosm of London (1808). © London Lives.

This monotonous regimen was not in itself sufficient to cope with the vagaries of workhouse life. The treatment of the sick, the pregnant, the very old and very young required further rules. The master was also given some latitude in both the punishment and reward of individuals, though as he did not have a judicial function of any kind, all punishments needed to be non-corporal, and normally took the form either of confinement in the dark hole or else the denial of food or privileges. The infirmary of St. James's workhouse was largely exempt from the orders enforced in the rest of the house, being under the authority of the surgeon, apothecary and mistress of the infirmary, and depending on the master primarily for the supply of fresh linen, clothes and cooked meals. Similarly the hours of work for the inmates employed in the kitchen and laundry were determined by the members of staff directly responsible -- the cook and laundry maid.

The conditions described by the rules of St. James's workhouse were good. The ability to go out of the house on Sundays and the quality of the diet compare favourably to most other London houses. In particular, the meals provided were both reasonably varied and made up of extremely filling ingredients. The plum pudding served the inmates each Saturday was made according to the following recipe:

Poor ffolkes must be glad of Pottage. c.1700. British Museum Schriber English 68. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Poor ffolkes must be glad of Pottage. c.1700. British Museum Schriber English 68. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Smaller houses made do with many fewer rules and employees, but generally sought to create precisely the kinds of conditions evident at St James.13

London Workhouses in 1776-7

According to the 1776-7 Parliamentary enquiry, by this date parochial institutions could be found in the following parishes. (The spelling and categorisation is reproduced as recorded in the original Parliamentary Papers, and the numbers accommodated are in parentheses.)

Workhouses in the City of London, 1776, fig.2.4. David Green, Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1870, Farnham, Surrey, 2010. © David Green.

Workhouses in the City of London, 1776, fig.2.4. David Green, Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1870, Farnham, Surrey, 2010. © David Green.

London City - Within the Walls

- Allhallows - Barking (70)

- St Andrew Undershaft (50)

- St Anne and St Agnes Within - Aldersgate (28)

- Christ Church (80)

- St Dunstan's in the East (70)

- St Ethelburga (48)

- St Katherine Coleman (30)

- St Katherine Creechurch (45)

- St Olave in Hart Street (56).

London City - Without the Walls

- St Andrew - Holborn (120)

- St Botolph Without - Aldgate (300)

- St Botolph Without - Bishopsgate (250)

- St Bridget (220)

- St Dunstan in the West (72)

- St Sepulchre Without - Newgate (279)

- St Giles Without - Cripplegate (260).

Westminster

- St Anne (150)

- St Clement Danes (350)

- St George - Hanover Square (700)

- St James (650)

- St Margaret and St John the Evangelist (420)

- St Martin in the Fields (700)

- St Mary le Strand (50)

- St Paul - Covent Garden (300).

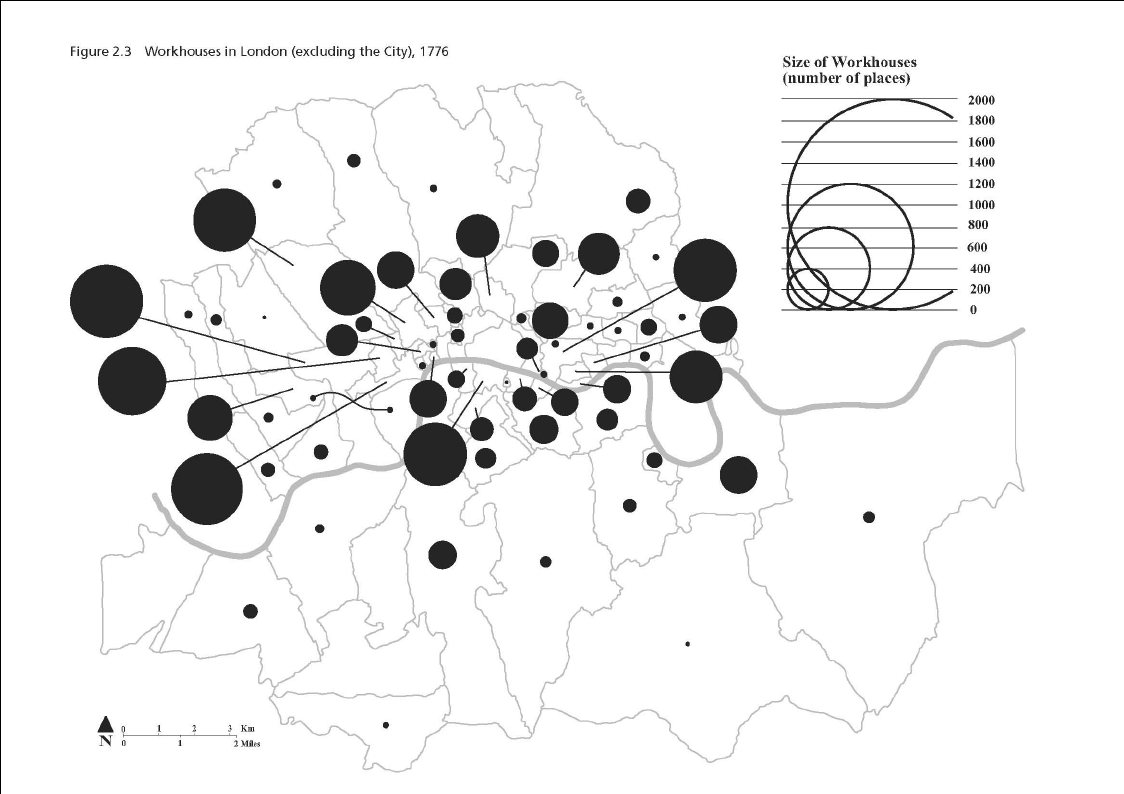

Middlesex within the Bills of Mortality

Workhouses in London (excluding the City), 1776, fig.2.5. David Green, Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1870, Farnham, Surrey, 2010. © David Green.

Workhouses in London (excluding the City), 1776, fig.2.5. David Green, Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1870, Farnham, Surrey, 2010. © David Green.

- St Anne (90)

- St Botolph Without - Aldersgate (240)

- Christ Church (340)

- St Dunstan - Stepney (150)

- St Giles in the Fields and St George - Bloomsbury (520)

- St George (500)

- St George the Martyr's and St Andrew - Holborn (350)

- St James - Clerkenwell (300)

- St John - Hackney (22)

- St John - Wapping (260)

- St Leonard's - Shoreditch (250)

- St Luke (400)

- St Mary - Islington (60)

- St Mary Matfellon - Whitechapel (600)

- St Matthew - Bethnal Green (400)

- St Paul - Shadwell (350)

- Rolls Liberty (50)

- Saffron Hill, Hatton Garden and Ely Rents Liberty (140)

- St Sepulchre (20)

Back to Top | Introductory Reading

Contractors, Private Workhouses and Baby Farms

One clause of the Workhouse Test Act (1723) provided for parishes to contract "with any person or persons for the lodging, keeping, maintaining and imploying any or all such poor ... as shall desire to receive relief or collection from the same parish", effectively laying the legal groundwork for smaller parishes to contract out their poor relief obligations to either other parishes or private individuals.14 This was a particularly popular strategy for the small parishes of the City of London, which normally had too few paupers to justify the creation of a house of their own.

In effect, Matthew Marryott functioned as a private contractor in this mould, normally taking full control of a parish's provision for a set sum. Others followed Marryott's example, including Thomas Mico and his wife. In 1727 Mico and Thomas Worrall contracted with St Martin in the Fields for the care of its poor, in direct succession to Marryott; Mico and his wife acting as master and mistress of the house, and employing the poor, while Worrall entered into a separate contract to keep the accounts, look after the sick poor, and manage the buying of provisions. By 1739 Mico had long since left St Martin and was contracting for the care of the poor of Enfield; agreeing "to take the men, women and children at 2s. a head per week,.... and ... to find them in meat, drink, washing soap, and firing, candles and all other necessaries".

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Miscellaneous Parish Papers, 17th August 1707-7th September 1778, 1280A, LL ref: GLDBPM306140002.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Miscellaneous Parish Papers, 17th August 1707-7th September 1778, 1280A, LL ref: GLDBPM306140002.

There were many others. During the 1730s and early 1740s John Thruckstone sought contracts with London parishes for both the care of paupers in his own workhouse at Tottenham High Cross, and for the management of several parish houses. In 1733 he contracted with St Dionis Backchurch for the care of their poor, and in the following year he contracted with both St Michael Cornhill and St Helen Bishopsgate. The contract entered into between Thruckstone and St Dionis Backchurch is entirely typical. In it Thruckstone agreed to receive and maintain all the parish poor, put out children to appropriate apprenticeships, indemnify the parish against legal costs relating to settlement, and pay the costs of burial and medical care for a set sum of £167 5s per year.

In the nine years following 1733 Thruckstone applied to three more parishes for the care of their poor, St Leonard Shoreditch in 1737, St Clement Danes in 1742, and St Andrew Undershaft in 1742. Other men and couples seeking similar contracts in these decades included John Smith, Christopher Stafford, Samuel Tull, John Stoke, and Solomon Gardiner and his wife. John Smith, for instance, can first be identified as master of the workhouse belonging to St Andrew Undershaft in 1742, when the parish put his position up for re-appointment and he unsuccessfully competed with five other people for the contract for the care of the poor of that parish.15 By 1747, he was running an independent workhouse at Tottenham High Cross, and also had a contract with St Martin Vintry. These men gradually took over the administration of a large number of London workhouses, and gradually developed a series of free-standing non-parochial houses located principally at Hoxton, Tottenham High Cross and Mile End Old Town. During most of the eighteenth century, the charges levied for the care of the poor were calibrated to the kind of pauper being supported, and could range from 1s 6d per week for a healthy pauper able to contribute to their support through labour, to 4s a week for the less physically able. By the end the century, the charges levied had become standardised at between 4s and 6s per week, per pauper.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Miscellaneous Parish Papers, 17th August 1707-7th September 1778, 1280A, LL ref: GLDBPM306140002.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Miscellaneous Parish Papers, 17th August 1707-7th September 1778, 1280A, LL ref: GLDBPM306140002.

The ways in which vestries used these houses varied from parish to parish. Some reserved these contract houses for the most dependent poor, or the insane; while others used the offer of the house as a deterrent threat against the casual poor, while allowing pensioners and established paupers to live independently in their own homes, and maintaining only a small proportion of their poor in a contract workhouse. This latter strategy allowed overseers to apply a workhouse test without actually going to the expense of maintaining those in temporary need, while also providing centralised nursing and medical care.

The size and specialised facilities available through these houses grew over the course of the century, and by the beginning of the next century took the form of a relatively few very large houses, including James Robertson's establishment at Hoxton, which by 1815 was thought to house up to 300 paupers from forty different City parishes; Thomas Tipple's pauper farm at 12 Queen's Street, Hoxton, which had 230 places and was used by seventeen City parishes; and Edward Deacon's two houses at Mile End and Bow, which between them housed 520 paupers, and served over forty City parishes.16

The passage of the Act for the better Regulation of the Parish Poor Children (1767), sponsored by Jonas Hanway, which required that all parish children under the age of four should be nursed in the countryside at least three miles from London and Westminster, also encouraged the development of a sub-set of contract workhouses, known as baby farms.17 It was at a farm of this sort that the infant Oliver Twist was confined and starved.

Among the parishes included on this site, St Dionis Backchurch made extensive and long-term use of several different contract workhouses and pauper farms from 1733. Overall, the parish appears to have taken some care of the poor it housed in this manner, and the existence of series of Workhouse Inquest Minute Books (IW), recording details of the parish officers' monthly visit to the poor in several workhouses in Hoxton, gives a good insight into conditions and arrangements.

Henry Fielding's Plan

The ever more disparate nature of poor relief provision in London ensured that few projectors or politicians could contemplate a single unified solution to the issue of housing and employing the poor of the metropolis. On a national scale politicians and projectors such as William Hay and Sir Richard Lloyd had long argued for "county" workhouses, as a means of overcoming the problems associated with amateurish parochial administration and the costs of policing pauper settlement. But the only substantial advocacy of this kind of solution for London, following the failure of the London Workhouse, was produced by Henry and John Fielding. Published in the form of three separate pamphlets, they developed a broad analysis of social problems and policing in London, depicting them as facets of a single issue:

- Henry Fielding's, Enquiry in to the Causes of the Late Increase of Robbers (1751)

- Henry Fielding's Proposal for Making an Effectual Provision for the Poor which specifically addressed the need for a general county workhouse (1753)

- John Fielding's Plan for Preventing Robberies within Twenty Miles of London (1755), published after Henry Fielding's death.

The workhouse proposed by the Fieldings combined a county workhouse for Middlesex with a house of correction. Much of the programme of reform in these pamphlets was eventually implemented in the following decades. The Middlesex-wide workhouse they proposed was designed to accommodate 5,000 paupers (3,000 men and 2,000 women), and a further 600 petty criminals in the associated house of correction. One nineteenth-century commentator, C. D. Brereton, accused Fielding of attempting to, "effect the reformation of manners and the employment of the poor, by brick and mortar, and architectural devices". 18 The house was never built, but its proposal forms part of a major building programme that eventually resulted in the rebuilding of Newgate Prison, and many of the other major carceral institutions of greater London.19

Beggars leaving Town for their Workhouses, John T. Smith, Vagabondiana, Or, Anecdotes of Mendicant Wanderers, 1817. © London Lives.

Beggars leaving Town for their Workhouses, John T. Smith, Vagabondiana, Or, Anecdotes of Mendicant Wanderers, 1817. © London Lives.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keywords Pauper Farm:

Lives using the keyword Workhouse:

- Ann Somerville, fl. 1790-1796

- Catherine Jones, fl. 1757-1783

- Elizabeth Bennett, fl. 1765-1792

- Elizabeth Yexley, d. 1769

- George Clegg, fl. 1773-1787

- Isabella Cousins, b. 1765

- Jane Vobe, b. 1775

- John Conway, fl. 1775-1786

- Mabel Hughes c.1678-1755

- Margaret Larney, c. 1724-1758

- Mary Broadbent, fl. 1726-1777

- Mary Partridge b. 1764

- Parmenas Adcock, b. 1774

- Paul Patrick Kearney, fl.1727-1771

- Percy Allen, fl. 1720-1723

- Sarah Gale, b. 1767

- Sarah Pilch fl. 1793-1818

- Thomas Vobe, b. 1767

Introductory Reading

- Green, David. Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law 1790-1870. Farnham, Surrey, 2010.

- Hitchcock, Tim. Down and Out in Eighteenth-Century London. 2004, ch.6.

- Murphy, Elaine. The Metropolitan Pauper Farms 1722-1834. London Journal, 27:1 (2002), pp. 1-18.

- Slack, Paul. Hospitals, Workhouses and the Relief of the Poor in Early Modern London. In Grell, Ole Peter and Cunningham, Andrew, eds, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500-1700. London and New York, 1997, pp. 234-51.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 The most detailed analysis of the parliamentary returns for this year can be found in David Green, Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law 1790-1870 (Aldershot, 2010), pp. 146-9. ⇑

2 14 Charles II c.12. ⇑

3 See Paul Slack, Hospitals, Workhouses and the Relief of the Poor in Early Modern London, in Ole Peter Grell and Hugh Cunningham, eds, Health Care and Poor Relief in Protestant Europe, 1500-1700 (1997), pp. 234-51; Paul Slack, From Reformation to Improvement: Public Welfare in Early Modern England (Oxford, 1999); and Joanna Innes, Prisons for the Poor: English Bridewells, 1555-1800, in F. Snyder and D. Hay, eds, Labour, Law and Crime: An Historical Perspective (Tavistock, 1987), pp. 42-122. ⇑

4 Tim Hitchcock, ed, Richard Hutton's Complaints Book: The Notebook of the Steward of the Quaker Workhouse at Clerkenwell, 1711-1737 (London Record Society, 24, 1987), Introduction. ⇑

5 For a discussion of the Bristol Corporation see Mary Fissell, Patients, Power and the Poor in Eighteenth-Century Bristol (Cambridge, 1991), ch. 4. ⇑

6 Stephen M. MacFarlane, Social Policy and the Poor in the Later Seventeenth Century, in A. L. Beier and R.A.P. Finlay, eds, London, 1500-1700: The Making of the Metropolis (1986), pp. 252-77. ⇑

7 7 George I c. 7; also frequently referred to as Knatchbull's Act. ⇑

8 Tim Hitchcock, Paupers and Preachers: The SPCK and the Parochial Workhouse Movement, in Lee Davison, et al., eds, Stilling the Grumbling Hive: The Response to Social and Economic Problems in England, 1689-1750 (Stroud, 1992), pp. 145-66. ⇑

9 Timothy V. Hitchcock, The English Workhouse: A Study in Institutional Poor Relief in Selected Counties, 1696-1750 (Oxford University DPhil., 1985), pp. 270-8. ⇑

10 Kevin Siena, Venereal Diseas, Hospitals and the Urban Poor: London's "Foul Wards," 1600-1800 (Rochester, New York, 2004), pp. 135-80. ⇑

11 Matthew Marryott, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004-10; requires subscription). ⇑

12 Tim Hitchcock, Down and Out in Eighteenth-Century London (2004), pp. 125-50. ⇑

13 An Account of Several Workhouses (2nd edn, 1732), pp. 54-5. Hitchcock, English Workhouse, pp. 167-74. ⇑

14 7 George I c. 7, An Act for Amending the Laws relating to the Settlement, Imployment and Relief of the Poor. ⇑

15 London Metropolitan Archives (was London Metropolitan Archives), St Andrew Undershaft, Vestry Minutes, 1726-1759, Ms. 4118, vol. 2, p. 134. ⇑

16 Elaine Murphy, The Metropolitan Pauper Farms 1722-1834, London Journal, 27:1 (2002), pp. 1-18. ⇑

17 7 George III c.39. ⇑

18 Quoted in Kathryn Morrison, The Workhouse: A Study of Poor-Law Buildings in England (Royal Commission on the Historical Monuments of Engalnd, 1999), p. 18 ⇑

19 Malvin Zirker, Fielding's Social Pamphlets (Berkeley, California, 1966). For the rebuilding of London's prisons, see Christopher Chalklin, The Reconstruction of London's Prisons, 1770-1799: An Aspect of the Growth of Georgian London, London Journal, 9 (1983), pp. 21-34. ⇑