St Clement Danes

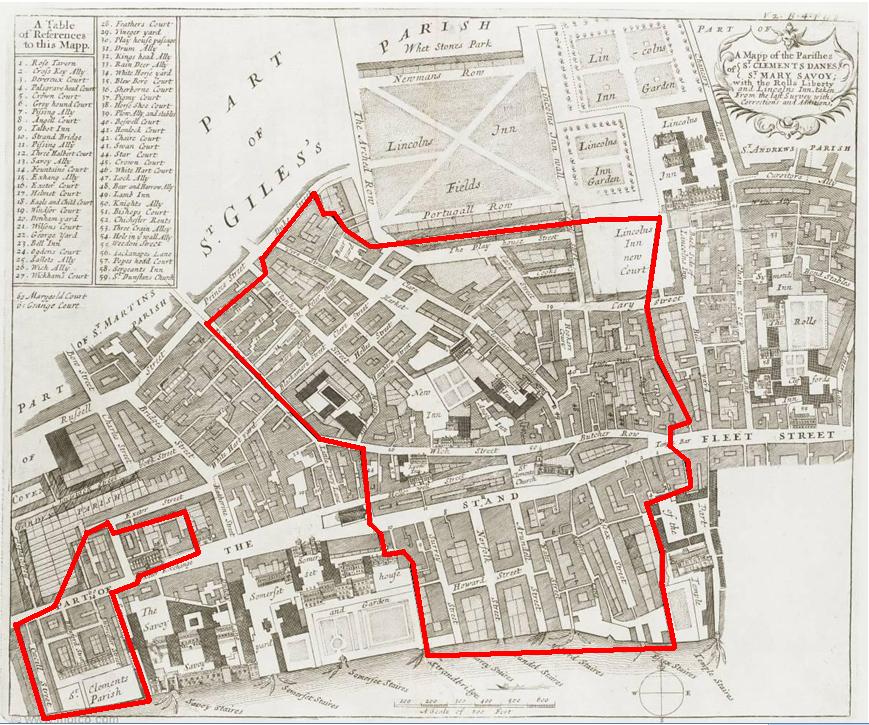

St Clement Danes; John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, 1720. © Motco Enterprises Ltd, 2003 (base map only).

St Clement Danes; John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster, 1720. © Motco Enterprises Ltd, 2003 (base map only).

Introduction

A large urban parish located just outside the boundary with the City of London to the west, St Clement Danes was home to both the disorderly population of Clare Market and Wych Street, and the much more orderly denizens of the Inns of Court. With well over 10,000 inhabitants St Clement required a sophisticated and extensive system of policing and poor relief, the records of which are reproduced here. But this system of local governance had to contend with frequent and fierce local opposition, and a culture of political activism that placed St Clement at the heart of what became known as radical Westminster.

Location

St Clement Danes sits in Westminster on the edge of the City of London and is divided into two geographically separate areas, encompassing forty-four acres in total (including parts of the River Thames). Its main section stretches from Lincoln’s Inn Fields southwards to the river. Its eastern boundary follows that of the City, tracing a line from the New Court southwards along Sheer Lane to Temple Bar astride Fleet Street, and south to the riverside. This boundary is shared predominantly with the Liberty of the Rolls and the Temple. To the west, the parish shares a boundary with St Mary le Strand, following a line next to Somerset House, northwards, across the Strand and Wych Street, and up to Drury Lane. To the north and west the parish is adjacent to St Giles in the Fields and St Martin in the Fields, respectively. There is also a separate western element of the parish, located further along the Strand, which incorporates a small stretch of the river (given over to a timber yard in the mid-eighteenth century), and a section of built up land composed of Cecil Street, Dirty Lane, Beaufort Buildings, and Fountain Court south of the Strand, and the Exeter Exchange to the north. This western addition is sandwiched between St Mary le Strand and St Martin in the Fields.

Temple Bar in the Strand, London, Thomas I. Malton. The Courtauld Institute of Art, D.1952.RW.4316. © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

Temple Bar in the Strand, London, Thomas I. Malton. The Courtauld Institute of Art, D.1952.RW.4316. © The Samuel Courtauld Trust, The Courtauld Gallery, London.

The parish was large, densely populated and made up of a series of distinct neighbourhoods defined by class and economic function. To the north were the Inns of Court, giving the parish a strong legal presence. Lincoln’s Inn itself was beyond the parish boundaries, but several smaller Inns, including the New Inn, Angel Inn and Clement's Inn were within St Clement Danes. Just to the west of this legal district lay Clare Market, the second largest meat market in London after Smithfield, and the centre of the victualling trades within the parish. The market formed part of a north-south axis along Vere Street, dominated by food retailing. The butchers’ boys from the market were famous in the eighteenth century for monopolizing the playing of rough music at weddings and playing the role of groundlings in the theatres of the neighbourhood. Clare Market was also a notable point of origin for many of the men and women tried for participating in the Gordon Riots. In the early eighteenth century John Strype described Clare Street, Houghton Street and Holles Street, all leading from Clare Market to Stanhope Street, as "well built and inhabited", but he also noted pockets of poverty in small courts north of the market, and off Stanhope Street.1

To the east, Sheer Lane marked the parish boundary with the City, and formed the centre point of the parish’s literary and coffee house quarter. The Kit-Cat Club was located here, and Richard Steele depicts Isaac Bickerstaff as lodging at the north end of the lane. Jonathan Swift and Samuel Johnson also have notable connections to the parish.2

The largest and most important thoroughfare was the Strand, starting from Temple Bar which opened eastward to Fleet Street and ran directly westward, first past Butchers’ Row and onwards to St Mary le Strand, leading eventually into Charing Cross. Throughout the medieval and early modern period the Strand formed part of the traditional processional route tying the City to Westminster. It was, by the eighteenth century, also a commercial centre, home to shops and coffee houses, including the Turk’s Head at number 142. Almost parallel to, and just north of the Strand, ran Butchers' Row and Wych Street, which over the course of the eighteenth century became famous for their old fashioned wooden-framed buildings. Areas of deep poverty could be found in the courts and alleys running north from Butchers’ Row in particular. Heller Street, running westward from Butchers' Row just south of Wych Street, played host to large numbers of used clothing dealers.

South of the Strand, the parish was largely redeveloped in the seventeenth century, creating a series of wealthy streets and buildings running down to the Thames.

Local Government

Throughout the eighteenth century, a small part of St Clement Danes lay in the Duchy of Lancaster, but the substantive parish lay in the Liberty of Westminster and was at least nominally governed under the authority of the Court of Burgesses, which in turn derived its authority from the Dean and Chapter of Westminster Abbey, in relation to both the parish’s civil and ecclesiastical functions. The Dean and Chapter of Westminster in turn appointed a complex series of stewards, under-stewards and magistrates.

In 1737, William Maitland listed the parish officers and form of government as consisting of:

In practice, up until 1764 the governance of the parish rested awkwardly between the Court of Burgesses, the Middlesex Bench and a powerful closed or select vestry; each vying with the other over arrangements for poor relief and policing.

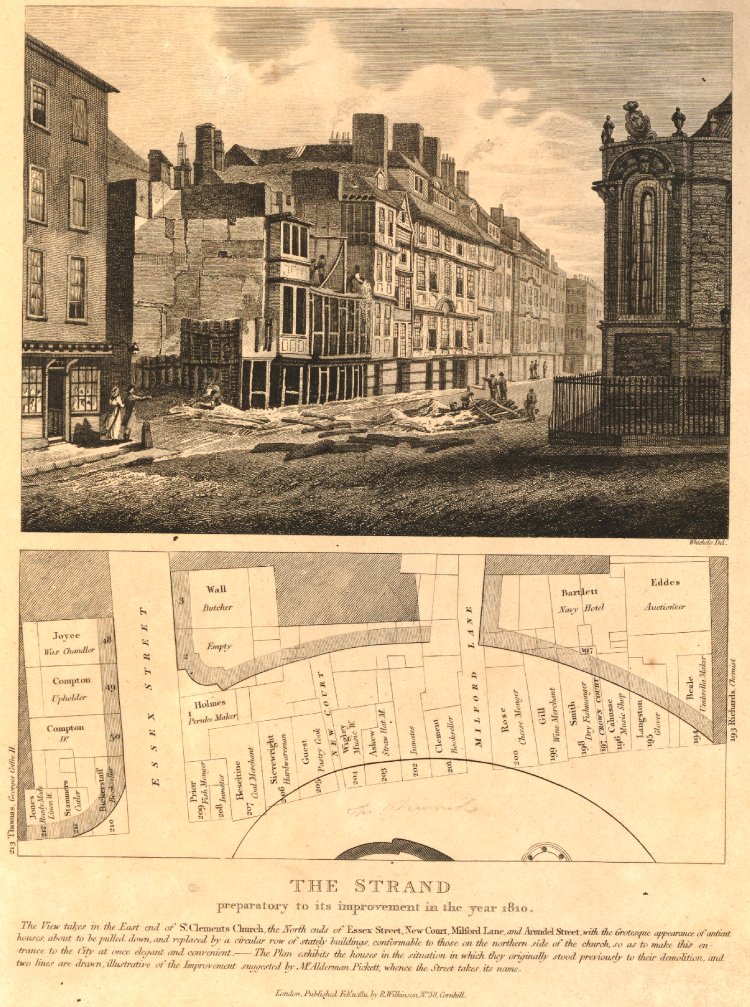

John Mayle Whichelo, The Strand, 1811. British Museum, Crace XVII.183. © Trustees of the British Museum.

John Mayle Whichelo, The Strand, 1811. British Museum, Crace XVII.183. © Trustees of the British Museum.

This situation was only clarified and reformed with the passage of two local Acts in 1764 and 1771. The first, for establishing a regular and Nightly Watch, and for maintaining, regulating, and employing the Poor within the parish of Saint Clement Danes, gave the parish authority to appoint and manage its own nightwatchmen.4 The same act also secured parliamentary authority for the establishment and local management of a parochial workhouse, and unusually for Westminster (which was almost universally governed through select vestries) the Act also enshrined the the right of all inhabitants to meet in the vestry for the purpose of appointing officers and examining parish accounts. 5

From 1764 a group of up to twenty-four substantial inhabitants were incorporated as Directors or Governors of the Nightly Watch and Beadles, and given authority to raise a local rate of up to 4d in the pound, appoint, pay and punish watchmen, and establish a comprehensive series of watch beats. The same Act also empowered the vestry, churchwardens and overseers of the poor to appoint "ten substantial and discreet persons... to be assistants to the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor" to act as a workhouse committee to raise a rate in support of the poor and manage a workhouse to be built in the parish. The act also empowered the committee to inflict corporal and other punishments on paupers in the workhouse, and to arrest and train children under 10 years old, begging in the Streets, and to keep them in the workhouse until the age of 21.

A general act of 1761 established commissioners for paving, cleaning and lighting the streets of Westminster as a whole, including St Clement Danes. There was, however, a large degree of disquiet about the powers vested in the commission and it was revised by an act of 1771, entitled, An Act to Amend and Render More Effectual Several Acts Made Relating to Paving, Cleansing and Lighting the Squares, Streets, Lanes and other Places within the City of Westminster and Places Adjacent.6 This transferred authority for raising rates and expenditure to a new parish paving committee, constituted in a similar way to the committees for the watch and for poor relief.

Population

Figures based on the Four Shillings in the Pound Tax of 1694 suggest a population of 9,920 in that year. Calculations based on the number of houses in the parish recorded in Hatton’s New View of London (1708) give a figure of 1,729 houses and perhaps 7,435 people for 1708; applying the same methodology to the number of houses listed in the 1732 New Remarks of London by the Company of Parish Clerks suggests 1,750 houses and 7,525 people. William Maitland’s History of London (1739) claims there were 1,691 houses in the parish, suggesting a population of 7,271 in that year.8

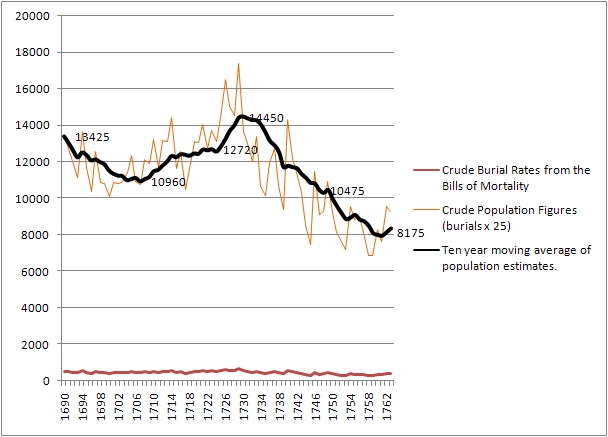

For the first half of the eighteenth century an annual population estimate can also be calculated from the number of burials listed in the Bills of Mortality. According to Dorothy George, these become less accurate from mid century, but by applying a multiplier of twenty-five (reflecting a notional annual death rate of 40 per 1000 inhabitants) a population trend can be arrived at. This methodology suggests a significantly higher population for the parish, ranging between a high of 14,500 people in 1730 to a low of just under 8,000 in 1761. For the seventy-two years analysed using this methodology, the parish had an average population of around eleven and a half thousand.

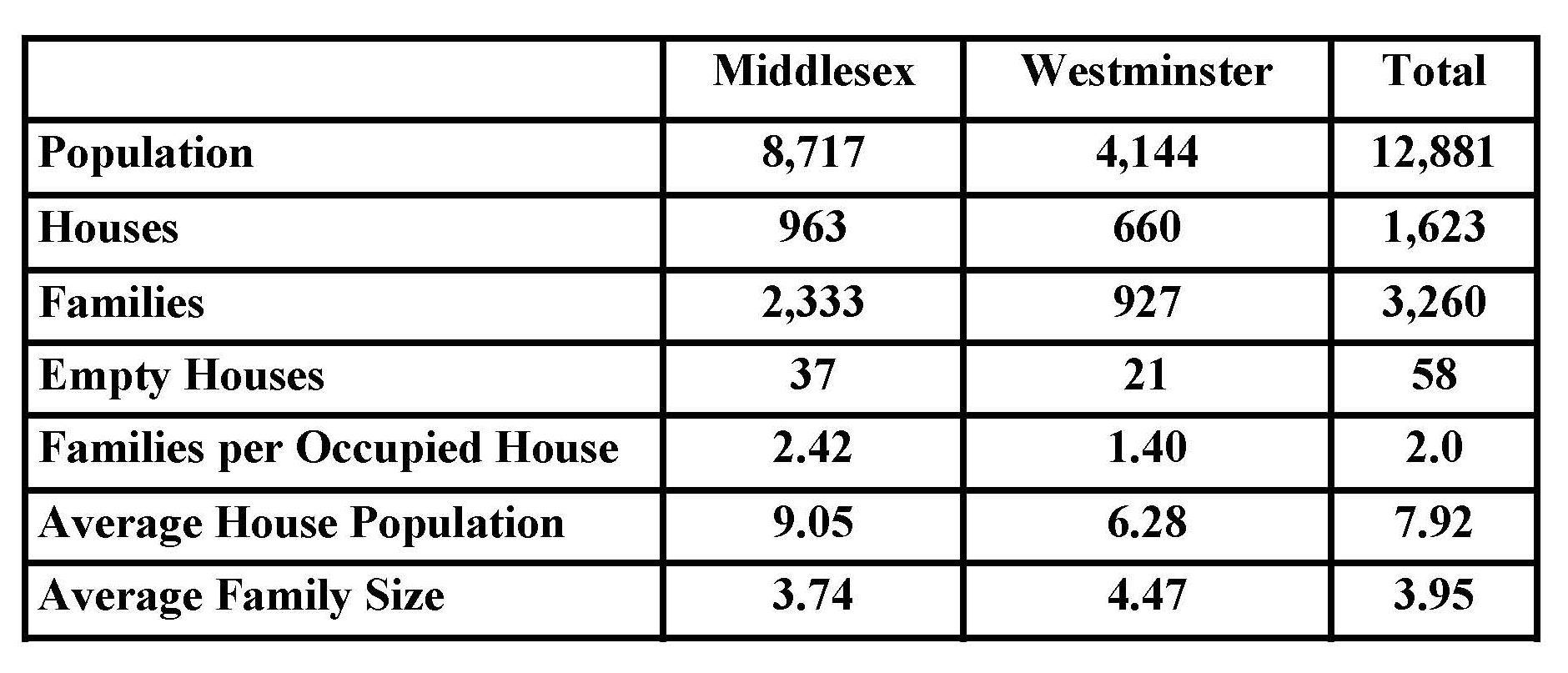

Overall, therefore, the population of the parish appears to have declined somewhat over the course of the eighteenth century. Yet the first reliable figures, which come from the 1801 census, suggest either that the earlier figures were underestimates, or that the parish had recovered by the end of the century. According to the census, in 1801 the parish had a population of 12,861 people, comprising 3,260 families, accommodated in 1,623 houses (58 further houses were recorded as being empty).

St Clement Danes Population as Derived from the 1801 Census.

St Clement Danes Population as Derived from the 1801 Census.

Distribution of Wealth

A simple measure of the character of the parish can be found in figures derived from the Four Shillings in the Pound levy of 1693-94. These suggest that St Clement Danes was by far the most densely populated parish in Westminster, with 95.9 households per hectare compared to an average of 13.7 households per hectare for Westminster as a whole (this latter figure is significantly skewed downwards by the large compass and small populated area of St Martin in the Fields at this date). The mean rateable value for households in the parish was £21 14s per year, placing St Clement in the middle of a spectrum from wealthy parishes such as St Paul Covent Garden (£34 8s), to poorer locations such as St Margaret’s (£11 9s). 9

A hundred years later, according to a 1798 Tax Assessment, the parish again emerges as comparatively well off. Some 85.5 per cent of houses were deemed wealthy enough to be liable for taxation (compared to only 39 per cent in demonstrably poor areas such as East Smithfield in St Botolph Aldgate). And of those liable, only 1 per cent were eventually excused on the grounds of poverty, compared to 7 per cent in East Smithfield.10

Economy

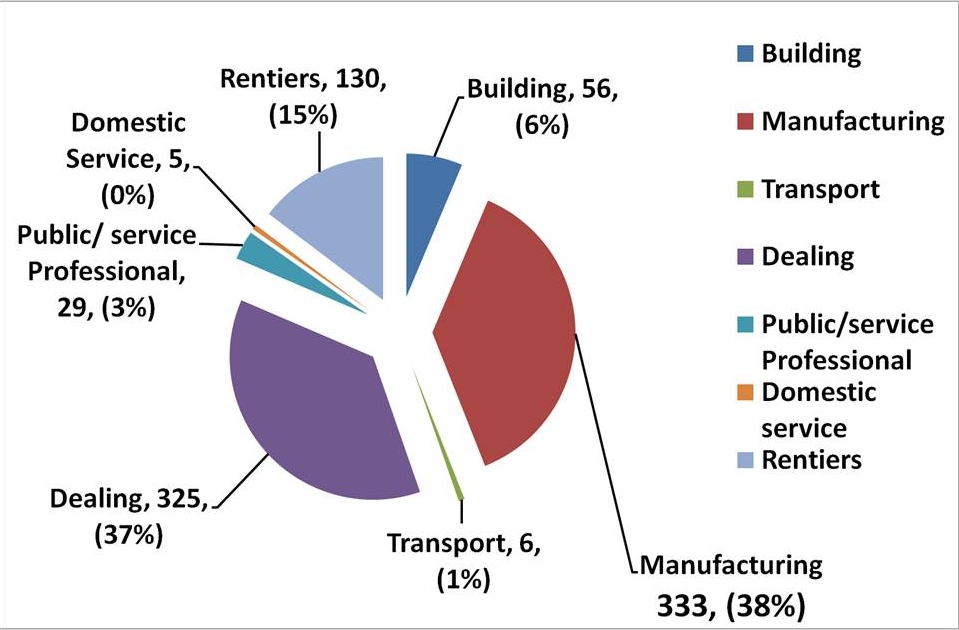

The 1749 Poll Books for the combined districts of St Clement Danes and St Mary le Strand give occupational details for 886 male householders. These occupations provide a snapshot of the economic activities undertaken in the parish, though they exclude women and the poor.

The Distribution of Occupations in St Clement Danes and St Mary le Strand, 1749. Categories containing fewer than 5 individuals have been excluded.

The Distribution of Occupations in St Clement Danes and St Mary le Strand, 1749. Categories containing fewer than 5 individuals have been excluded.

Manufacturing formed the largest single category of occupation, and can be broken down into its constituent components. The largest single components of this are Dress (180) and Dress Sundries (32), with Drink Preparation (20) and Baking (15), coming third and fourth. In contrast Dealing, the second largest occupational category, was more varied, with food distribution, hoteliery, and the wine and spirits trades dominating.

Overall, this distribution broadly reflects the character of occupations which Leonard Schwarz found for London as a whole from an analysis of insurance documents for the period 1775-1787, though in that sample Dealing was even more dominant, accounting for 48.2 per cent of all occupations. 11 It is important to remember, however, that this sample is based on records reflecting only part of the population. The poll books exclude women, and in any case capture only the top 15 to 20 percent of men, hiding a varied population of poorer workers. The small number of domestic servants listed, despite their substantial presence among the workforce, reflects these exclusions.

Housing

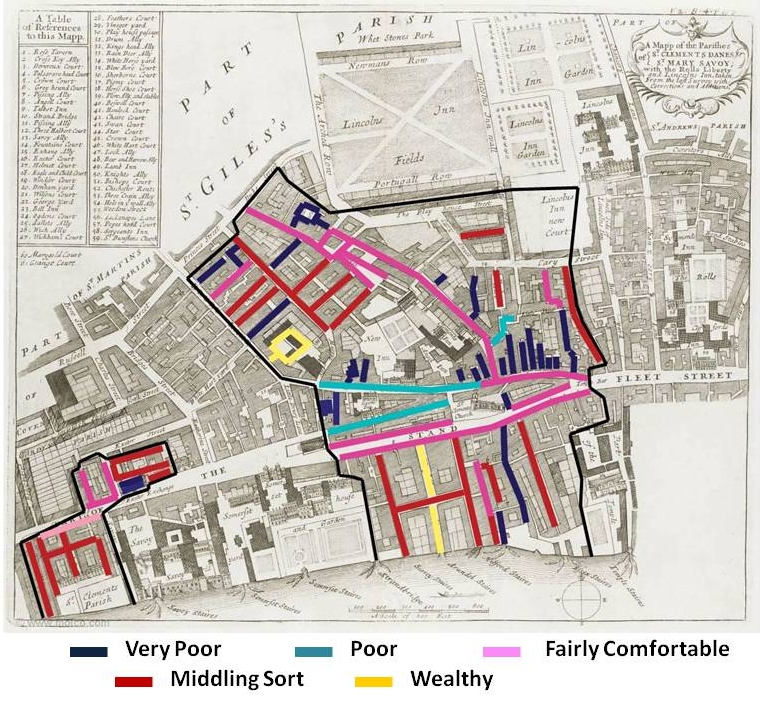

The social composition of St Clement Danes as described by John Strype in 1720 © Motco Enterprises Ltd, 2003 (base map only).12

The social composition of St Clement Danes as described by John Strype in 1720 © Motco Enterprises Ltd, 2003 (base map only).12

Although, on average, the parish was reasonably prosperous, it contained areas of old and dilapidated housing that in turn accommodated pockets of deep poverty. One measure of the geographical distribution of poverty in the parish, and the location of houses of very different character, can be found in John Strype’s 1720 description of the many of the streets of the parish.

Wealthy and middling sort neighbourhoods, next to Somerset House, in the roads leading down to the river and to the east of Drury Lane, hid ongoing and intractable pockets of real squalor. Part of the problem lay with the housing stock. Butchers' Row and Wych street, in particular, were famous for the cramped and damp medieval wooden-framed buildings which overhung the roadway, and were thought of, even in the eighteenth century, as reflecting a quaint "Old London". Even into the period of modern photography, Butchers' Row and Wych Street preserved the character of an older city.

Poor Relief and Charities

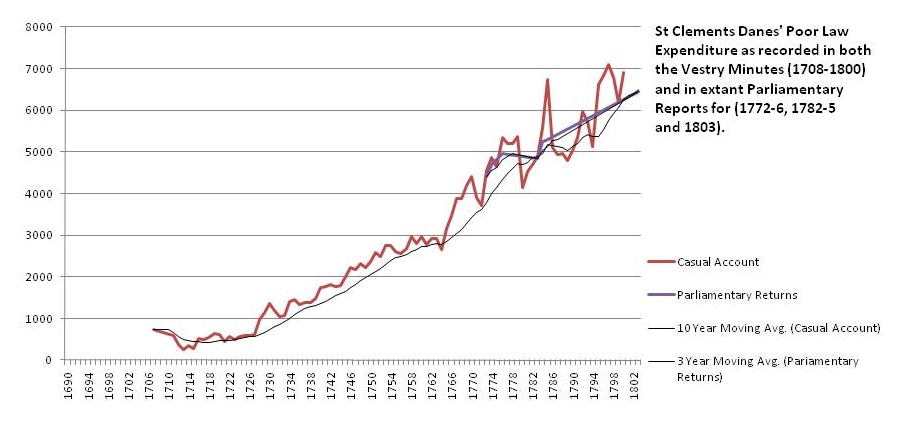

As a large urban parish St Clement Danes ran a substantial poor relief system. A measure of this effort can be found in the 1803 Parliamentary Abstract of Returns relative to the Expense and Maintenance of the Poor, which records the parish as having spent £6,896 13s 2¼d on relief in the preceding year on 334 workhouse inmates, 209 out-pensioners and 83 children under the age of fourteen.13

Parish records confirm this level of expenditure, and allow us to chart the substantial increase in relief expenditure by the parish from the beginning of the century and continuing steadily decade by decade, despite the apparently stable (or even declining) parish population.

St Clement Danes Poor Relief Expenditure, 1706 to 1803.

St Clement Danes Poor Relief Expenditure, 1706 to 1803.

At regular intervals through the first half of the eighteenth century the parish sought to establish a workhouse of some sort or other. In the 1690s and until at least 1710 the parish maintained a house in which a series of contractors employed the poor. Termed a workhouse, this house almost certainly took the form of a daily workshop rather than a residential establishment. There was also an abortive attempt to procure a special act of parliament in conjunction with St Martin in the Fields in 1708. And on 17 May 1726 the vestry minutes record a decision to build a new workhouse:

But popular opposition appears to have scuppered these plans through the 1730s and 1740s, during which decades several committees of the vestry were convened, reported, and let fall. In October of 1740, the number of "poor receiving alms exclusive of their children" was calculated at 402.

It was only in the 1760s, first as a result of the passage of the parish Watch Act,14, and then through the campaigning of Jonas Hanway (who held the parish to public censure for its practice in relation to the infant poor and nurses) that substantial change occurred.15

The Watch Act gave the parish authority to establish a workhouse over the objections of the wider populace, but this was not immediately implemented. Three years after the passage of the act, Jonas Hanway, as part of an excoriating exposé of parochial care of abandoned children, claimed:

Old Houses in Wych Street, A & J Bool, 1867. British Museum, Crace XVII.155. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Old Houses in Wych Street, A & J Bool, 1867. British Museum, Crace XVII.155. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Hanway went on to point to St Clement Danes as having one of the worst survival rates for abandoned infants of any London parish, and provided detailed statistics for the number of children dying while in parochial care. Hanway's pamphlet also reflects strongly on the role of individuals employed by the parish (in particular Hannah Poole). According to Hanway, while in Westminster as a whole the infant mortality rate (up to 12 months) for parish children stood at 67 per cent, that for children cared for by St Clement was 90 per cent (seventeen dead out of nineteen pauper children born or received under the age of one year).17

Hanway's solution was to send parish children out of London to nurse in the country, and following an earlier successful campaign to establish Registers of Parish Pauper Children (RC), his campaign eventually resulted in the passage of a further act in 1767, requiring that parishes within the bills of mortality put children to nurse in the countryside, at least three miles from the metropolis.

These legal developments and criticisms eventually resulted in St Clement building a substantial workhouse, opened in 1773, and in creating a well organised system for putting younger parish children to nurse in the countryside. This latter development is reflected in the parish's Enfield Books (BE), which from 1787 give details of nurses and their charges located in the area around Enfield, north of London.

By at least the 1780s the parish had gained a reputation as the best casualty parish (where relief for the poor was relatively easy to obtain) in London. See, for instance, Mary Brown's Bastardy Examination of January 1786, in which she is directed specifically to St Clement Danes for this reason. The parish also took the lead in apprenticing pauper children to northern woollen mills. Between 1786 and 1799, 64 girls and 125 boys were apprenticed by the parish, most of whom went to John Birch's, Backbarrow Mill, Cartmel, in Lancashire (now part of Cumbria).18

The parish was reasonably well endowed with charities. In the 180 years between 1480 and 1660 it was bequeathed over £4,463 13s for charitable purposes. These gifts included some £600 of property left by Richard Beddoe in 1603, and £400 left by Isaac Duckett in 1618 to reward faithful maidservants or to provide stipends at the time of their marriage. 19

The 1819 parliamentary returns of charitable donations suggest St Clement Danes was earning an annual income £979 17s from charitable investments. This included £345 used to support a charity school, £100 distributed to twelve poor widows, and a further £534 17s to support twelve almswomen. 20

Crime and Policing

In the decades on either side of 1700 the West End, including St Clement Danes, suffered the highest prosecution rates at sessions of any area in metropolitan Middlesex, reflecting high social tensions. Commitments to houses of correction were especially high, with recognizances and indictments running at 8.1 and 5.0 per 1000 inhabitants respectively for St Clement Danes, compared to 4.7 and 4.6 for the neighbouring parish of St Andrew Holborn. In comparison to the rest of Middlesex, the West End witnessed more indictments for vice offences, more women committed to the house of correction, and fewer female prosecutors, reflecting the intense activities of the Societies for the Reformation of Manners.21 Rates of felony prosecutions in 1719-22 were also high in the West End, with disproportionate numbers of pickpockets and thefts involving assaults.22

By the 1740s recorded indictment rates (both felonies and misdemeanours) reached one per 139 inhabitants, again one of the highest in greater London. In the same period the parish accounted for 3 per cent of all those hanged in greater London.23 The number of trials recorded at the Old Bailey in which the major streets of the parish were mentioned in evidence suggests the parish suffered from extraordinarily high rates of violent theft in the first half of the century.

From the 1740s through the 1770s the parish was the location of several initiatives for increasing the prosecution of vice and crime. As can be seen in the Vestry Minutes (MV), parish officials discussed ways of suppressing several forms of vice, disorderly houses, and robberies, including by offering rewards. When Bosavern Penlez was convicted in 1749 for allegedly participating in a riot which pulled down a brothel, the parish was a noted centre of hostility to his execution.24 In the 1760s and 1770s, William Payne, the reforming constable resident in Bell Yard just beyond the parish boundary in the Liberty of the Rolls, was particularly active. 25 The parish was in easy reach of the magistrate's court at Bow Street, and figures largely in the records of crimes prosecuted by Henry and John Fielding's Runners.

George Cruikshank, Tom Getting the Best of a Charley, 1824. Lewis Walpole Library 820.8.31.3. © The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

George Cruikshank, Tom Getting the Best of a Charley, 1824. Lewis Walpole Library 820.8.31.3. © The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

The parish supported the general Westminster Watch Bill of 1720, but on the failure of this bill did not follow the example of parishes such as St Martin in the Fields in pursuing an individual parish act until 1764, when a local watch act created a watch committee of up to 24 Directors or Governors. The committee was given the authority to raise a rate and organise a sufficient number of watchmen and watch boxes. The parish Watch house, or Roundhouse was located in the New Church Yard on Portugal Street, which also contained the last surviving set of public stocks in London.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keywords St Clement Danes:

Documents Included on this Website

- Books of Clothing Provided by the Parish (BC)

- Enfield Books: Registers of Parish Children put out to Nurse (BE)

- List of Inmates of St Clement Danes Workhouse in 1785 (LW)

- List of Securities for the Maintenance of Bastard Children (RR)

- Lists of Paupers Receiving Parish Relief (LP)

- Minute Books of Parish Vestry Sub-Committees (MO)

- Minutes of Parish Vestries (MV)

- Miscellaneous Parish Account Books (AO)

- Miscellaneous Parish and Bridewell Papers (PM)

- Overseer's Order Books: Goods Ordered by Workhouse Master (OO)

- Parish Apprenticeship Indentures and Registers (PA)

- Parish Clothing Books, with Names of Children at Nurse (BN)

- Pauper Settlement, Vagrancy and Bastardy Examinations (EP)

- Register of Pauper Settlement and Bastardy Examinations (RD)

- Register of Paupers Removed from the Parish (RV)

- Registers of Fortnightly/Monthly Parish Pensioners in 1733 (RP)

- Registers of Poor Children under Fourteen years in Parish Care (RC)

- Regular Parish Payments to Paupers (AP)

Back to Top | Introductory Reading

Introductory Reading

- Diprose, John. Some Account of the Parish of St Clement Danes. 1868-76, 2 vols.

- Schwarz, Leonard D. London in the Age of Industrialisation: Entrepreneurs, Labour Force and Living Conditions, 1700-1850. Cambridge, 1992.

- Sharp, Richard. The Religious and Political Character of the Parish of St. Clement Danes. In Clark, Jonathan and Erskine-Hill, Howard, eds, Samuel Johnson in Historical Context. Basingstoke, 2002.

- Spence, Craig. London in the 1690s: A Social Atlas. 2000.

Online Sources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster ... Written at First in ... 1598 by John Stow ... Corrected, Improved and Very Much Enlarged by John Strype (1720), Book 4, p.118. ⇑

2 John Diprose, Some Account of the Parish of St Clement Danes (1868-76), pp. 260, 168, 86. ⇑

3 William Maitland, The History of London from its Foundations by the Romans to the Present Time (1739), p.718. ⇑

4 4 George III c.55. ⇑

5 Sidney and Beatrice Webb, English Local Government from the Revolution to the Municipal Corporations Act. Vol.1: The Parish and the County, (1906, reprinted 1963), p. 150n. ⇑

6 11 George III c.22. ⇑

7 Based on Thomas Birch, A Collection of the Yearly Bills of Mortality, from 1657 to 1758 Inclusive (1759); Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks, A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 12, 1758 to December 11, 1759 (1759); ibid., A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 11, 1759 to December 9, 1760 (1760); ibid., A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 11, 1760 to December 15, 1761 (1761); ibid., A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 15, 1761, to December 14, 1762 (1762); ibid., A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 14, 1762, to December 13, 1763 (1763). ⇑

8 M. Dorothy George, London Life in the Eighteenth Century, (1925, 1965), p. 410; Robert B. Shoemaker, Prosecution and Punishment: Petty Crime and the Law in London and Rural Middlesex, c.1660-1725 (Cambridge, 1991). p. 327. ⇑

9 Craig Spence, London in the 1690s: A Social Atlas (2000), p.178. ⇑

10 Leonard D. Schwarz, Conditions of Life and Work in London, c. 1770-1820, with special reference to East London (Oxford University DPhil, 1976), pp. 345, 353. ⇑

11 Leonard D. Schwarz, London in the Age of Industrialisation: Entrepreneurs, Labour Force and Living Conditions, 1700-1850 (Cambridge, 1992), p. 254, Table A2.1. ⇑

12 Strype, Survey of ... London and Westminster , Book 4, pp. 113-120. ⇑

13 Parliamentary Papers, 1803-4 (175), Abstract of the Answers and Returns Made Pursuant to an Act... Intituled... an Act for Procuring Returns Relative to the Expense and Maintenance of the Poor, pp.724-5. ⇑

14 4 George III c.55 ⇑

15 Ivy Pinchbeck and Margaret Hewitt, Children in English Society. Vol. 1, From Tudor Times to the Eighteenth Century (1973). p. 185. ⇑

16 Jonas Hanway, An Earnest Appeal for Mercy to the Children of the Poor, (1766), p.3 ⇑

17 Hanway, Earnest Appeal, p.25 ⇑

18 Katrina Honeyman, Child Workers in England, 1780-1820: Parish Apprentices and the Making of the Early Industrial Labour Force, (Aldershot, 2007), p.59. ⇑

19 W. K. Jordan, The Charities of London, 1480-1660: The Aspirations and the Achievements of the Urban Society (1960), pp.42, 195-6, 185. ⇑

20 Parliamentary Papers, 1820 (28), Charitable Donations: --no. I.-- Return to an Order of the Honourable House of Commons, Dated 25 January 1819. ⇑

21 Shoemaker, Prosecution and Punishment, pp. 291-302. ⇑

22 Shoemaker, Prosecution and Punishment, p. 291. ⇑

23 Peter Linebaugh, Tyburn: a study of crime and the labouring poor in London during the first half of the 18th century, (Warwick University PhD, 1975) 2 vols., p. 60 ⇑

24 Peter Linebaugh, The Tyburn Riot against the Surgeons, in Douglas Hay, et al, eds, Albion's Fatal Tree: Crime and Society in Eighteenth-Century England (1975), p. 92. ⇑

25 Joanna Innes, Inferior Politics: Social Problems and Social Policies in Eighteenth-Century Britain (Oxford, 2009), pp.279-342. ⇑

Derived from the Bills of Mortality, 1690-1763.

Derived from the Bills of Mortality, 1690-1763.