Parish Relief

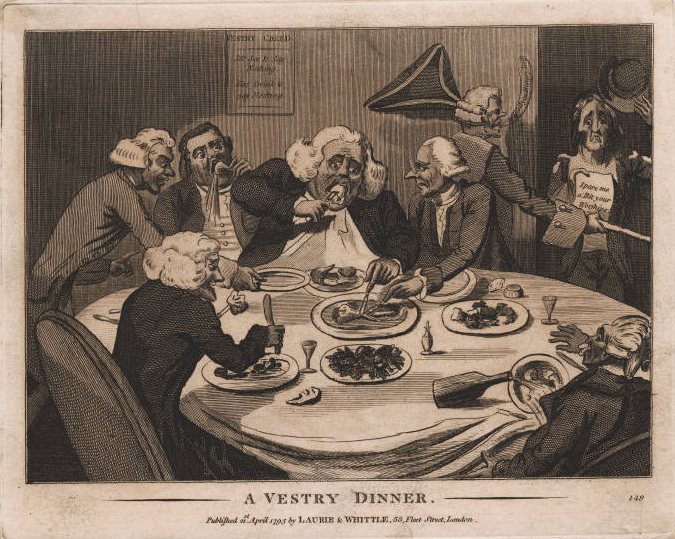

A Vestry Dinner, 1795. Lewis Walpole Libarary, 795.4.21.1. © The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

A Vestry Dinner, 1795. Lewis Walpole Libarary, 795.4.21.1. © The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Introduction

The parish formed the basic unit of local government throughout the eighteenth century and was legally charged with responsibility for poor relief. But this uniform legal obligation did not translate into uniform practice. Between the parishes of Westminster, the City of London and Middlesex there existed a wide variation in the generosity of relief provided and how it was delivered. This variegated pattern also changed decade by decade. The existence of charities to supplement taxation in the form of rates ensured that every parish was confronted with the need to navigate a unique funding landscape, in which local taxation, the rates, were more or less onerous depending on the size of local charities and collections. Similarly, while the churchwarden, working under the direction of the vestry and the supervision of a Justice of the Peace, and with the assistance of the overseer of the poor, was legally charged with the implementation of both the collection of the rates, and their distribution, the precise number of parish officers and employees and the character of their duties varied from parish to parish, ensuring that each community developed a unique system and tradition of governance.

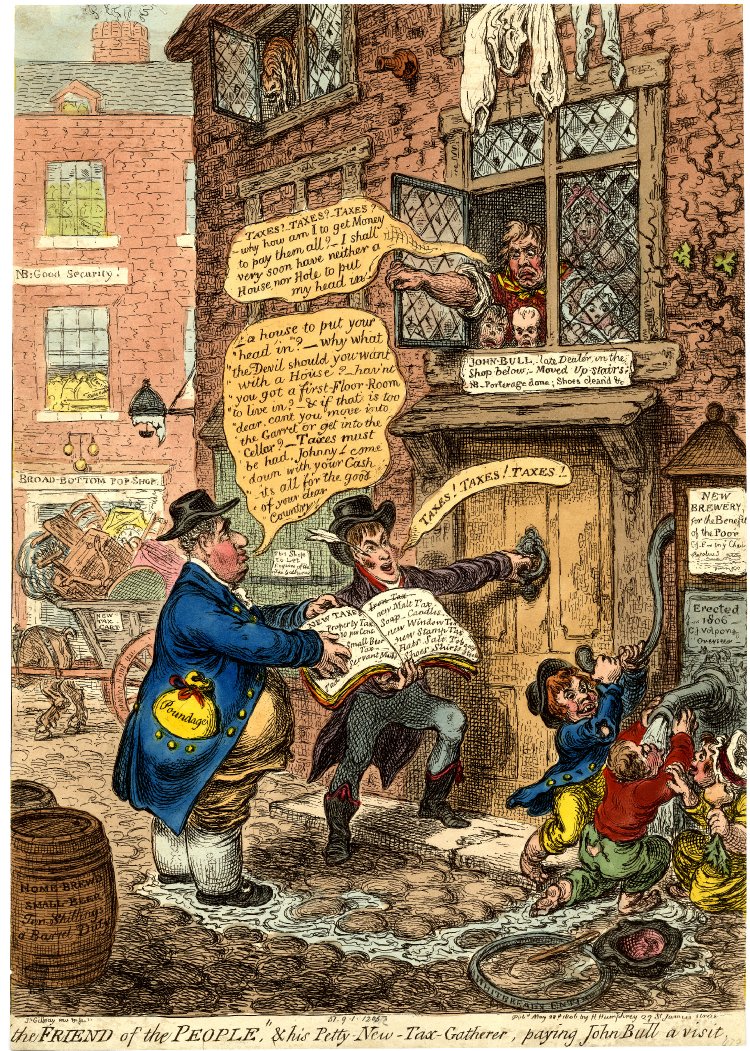

Rates

A rate is an assessment of the notional annual rental value of a property. So, for instance, a three story town house in St Clement Danes might be rated at £20 per year (the supposed income derived from renting it as a single dwelling for twelve months). Every house in a parish was assigned a rental value in this way. Commercial property could also be valued according to the stock held in a workshop or retail shop. A rate was then levied at a specific number of pence or shillings in the pound. A dwelling rated at £20 might, for instance, be subject to a seven pence levy, which would mean that the householder was obliged to pay 140 pence, or 11 shillings and 8 pence; seven pence for every pound in rateable value.

James Gilray, "The Friend of the people", & his petty-new-tax-gatherer, paying John Bull a visit, 1806. British Museum Satires 1057.A. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

James Gilray, "The Friend of the people", & his petty-new-tax-gatherer, paying John Bull a visit, 1806. British Museum Satires 1057.A. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

A parish might levy different rates for different purposes. In St Clement Danes for instance, separate rates were collected in the support of the night watch, the scavengers responsible for keeping the streets clean, for poor relief and for the church; whereas in St Dionis Backchurch, and in part because the watch was administered by the ward rather than the parish, a single church rate was sufficient.

Determining the precise level of necessary taxation at the beginning of the year was impossible. The cost of living, the exigencies of the weather and of illness, and the character of the overseer and churchwarden could all influence the level of expenditure. Fixing a single large demand at the beginning of the accounting year (in April) also put unreasonable financial strain on poorer householders. As a result most parishes levied a series of more modest rates as money was required through the year, collecting perhaps three, four or more exceptionally five rates as the year wound through.

In some parishes, such as St Dionis Backchurch, a separate parish officer, a sidesman, or collector might be appointed. Elsewhere, the collection of rates was subcontracted to a private individual who was charged with delivering a proportion of the amount a parish rate was likely to produce, and who was allowed to keep any extra money as compensation for his work.

Collecting the amount levied was frequently difficult. Appeals against the value set on an individual house, on issues of obligation (whether the owner or occupier of a house should pay), and simple pleas of poverty, all had to be heard by a Justice of the Peace, who was in turn charged with overseeing the probity of process. For some twenty years the records of these appeals and adjudications in petty sessions are recorded amongst the Vestry Minutes (MV) of St Clement Danes, and reflect a theatre of complex negotiation and conflict within the parish community.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 1745-49, B1067, LL ref: WCCDMV362080134.

Westminster Archives Centre, St Clement Danes, Vestry Minutes, 1745-49, B1067, LL ref: WCCDMV362080134.

Although they survive in large numbers, rate books have not been included on this site. They take the form of long lists of householders entered in the order in which their house sat on the street, with a note of the rateable value of the house, and the amount paid. However, the abstracted details of the rate books for Westminster for the years 1749, 1774, 1780, 1784, 1789, 1796, 1802, 1806 and 1818 have been included as part of the Westminster Historical Database, and can be searched by name and keyword.

Vestries, Churchwardens and Overseers

The vestry formed the collective decision-making body for the parish, and met where and as needed, with an annual meeting at Easter each year convened to audit accounts and appoint parish officers. Throughout the eighteenth century it could take a variety of forms - including either a closed vestry, in which a specific number of male householders (frequently twenty-four) acted as an oligarchy on behalf of the parish, recruiting new members as death and migration thinned their ranks; or else an open vestry, notionally including all householders and ratepayers (including women). Among the parishes whose records are included on this site, the vestry of St Dionis Backchurch was open, while the vestry at St Clement Danes started the century as a federated or closed vestry, but was then reformed into an open vestry following an Act of Parliament in 1764. The vestry at St Botolph Aldgate was composed of the '"ancient" inhabitants of the parish, who had served in parish offices.1 For St Botolph this created a system that was neither fully open nor closed, but nevertheless restricted membership of the vestry to more established parishioners. Whatever form the vestry took, it largely represented the interests of rate payers, rather than that of the recipients of poor relief, or the wider parish community. Even in parishes such as St Clement Danes, where popular involvement in parish politics was extensive, less than 10 per cent of parishioners had the right to attend and vote at the vestry; while in St Botolph this figure was between 1 per cent and 2 per cent of the population. The vestry retained direct oversight of raising money, managing bequests and distributing poor relief throughout the century, only becoming subject to substantial reform with the passage of Sturges-Bourne's Acts of 1818 and 1819.

At the annual Easter meeting of the vestry, which was frequently followed by a large celebratory feast, all parish officers were appointed to serve for the forthcoming year. At the same meeting, the outgoing officers' accounts were normally audited (although practice varied from parish to parish - in St Clement Danes the annual audit normally took place in September). The officers appointed could include one or more churchwardens, overseers of the poor, beadles, scavengers, sidesmen, collectors and constables. The precise number of officers depended on whether the parish was in the City, Westminster or Middlesex, and on its size and jurisdictional complexity. In City parishes such as St Dionis Backchurch, ward officers and common councilmen were also appointed by the vestry at this time. Fines levied in exchange for not serving in a parish office formed a significant and growing source of parochial income.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Churchwarden's Account Books, 25th March 1776 - 15th May 1783, 4222/4, LL ref: GLDBAC300100285.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Churchwarden's Account Books, 25th March 1776 - 15th May 1783, 4222/4, LL ref: GLDBAC300100285.

Legally, the churchwarden was the senior parish officer, and his duties included all those of an overseer of the poor, but in practice churchwardens usually kept separate accounts, and gave over full responsibility for poor relief to the overseers.2 In smaller parishes such as St Dionis Backchurch the churchwarden might double up as the overseer, with the assistance of a collector for the rates. This was the practice at St Dionis Backchurch until after mid century, when a pattern of appointing two churchwardens, two overseers, and two collectors was put in place. In larger parishes such as St Clement Danes, two churchwardens and three overseers were recruited each year; while the work of collecting the rates was subcontracted to private individuals. This arrangement was only modified with the establishment of a parish workhouse in 1772, and the creation of a separate workhouse committee and a group called the Guardians of the Poor, the last mandated by the 1767 Act for the Better Regulation of the Parish Poor Children.3 The most complex arrangements amongst those found in the parishes whose records are included here can be found in St Botolph Aldgate, where two churchwardens and four overseers were appointed each year, each of whom took responsibility for a different part of the parish.

In all cases, however, the first port of call for any pauper seeking relief was the overseer of the poor. It was the overseer who managed casual relief - the few pence here and there given on demand - and who oversaw the distribution of parish pensions and charitable legacies (frequently distributed on a particular day each month or year, respectively). It was the overseers, subject only to an appeal to a Justice of the Peace or an order of vestry, who determined who received relief, and who was turned away. And it is in the Overseers Accounts (AP) that the best evidence for the daily workings of poor relief can be found.

Because the position of churchwarden and overseer were filled for just a year by men of very different backgrounds, the records generated by them varied enormously. Most parishes managed to sustain a consistent pattern of accounting only through the intervention of a parish clerk, and the discipline imposed by the annual Easter audit when a Justice of the Peace in vestry signed-off the accounts, and determined how much money the overseer for the year needed to pass on to his successor, or alternatively might expect to recoup from him.

Pensions, Collection and Charities

Increasingly over the course of the eighteenth century London parishes resorted to parochial and contract workhouses, made use of the new associational charities, or relied on the quasi-institutional care of parish nurses. But the basic form of parish relief remained the pension and the casual payment. Even in parishes that managed their own workhouse, or contracted out part of their relief obligation to a private workhouse, paupers were frequently allowed to live independently and were given a limited pension. Even those London parishes that adopted the Workhouse Test Act, allowing them to refuse relief to anyone outside of the workhouse, found that providing casual relief was normally the cheaper option, and few parishes managed to sustain a workhouse test for very long.

But not all parish pensions or payments, nor all parish paupers, were equal.

William Hogarth, The Distressed Poet, 1737. BMAG 1934P500. © Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery.

William Hogarth, The Distressed Poet, 1737. BMAG 1934P500. © Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery.

In some cases, as in St Dionis Backchurch, the gap between the best-off parish pensioners and the most desperate casual pauper was extensive. From the late 1730s, the parish accepted substantial donations from residents in exchange for annuities for their widows of between £20 and £100 a year for life. This select band of widower pensioners probably did not see themselves as parish pensioners, but they were; and they were very comfortably provided.

This ambiguity is equally present in relation to the very desirable roles of almshouse resident and recipient of named charities. The twelve elderly widows and ex-householders accommodated in the almshouses located in the churchyard at St Clement Danes, and who received the benefit of Palmers' Charity, or indeed the twenty-eight deserving widows who received eight shillings each on both New Year's Day and Good Friday, were probably just as uncomfortable with the role of parish pensioner as were the annuity holders of St Dionis Backchurch. And the intrusive examination of all almshouse residents insisted upon by the vestry at St Clement Danes in 1789 in combination with the ongoing debate over who had the right to install a widow in the houses suggests that many other parishioners saw this resource in a more favourable light than mere parish relief.

Closer to most historians' notion of a parish pensioner were the recipients of collection, money collected after divine service for the use of the poor, and normally used to provide ongoing support for only the most deserving of decayed householders.4 The strict division maintained in St Dionis Backchurch between income derived from the rates and that collected in church, and the strict division between the groups of pensioners who received this income, speaks of a clear social divide amongst the parish poor, with collection being reserved primarily for the elderly and the respectable.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Churchwarden's Account Books, 1729 - 1762, 4215/2, LL ref: GLDBAC300060032.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Churchwarden's Account Books, 1729 - 1762, 4215/2, LL ref: GLDBAC300060032.

This same kind of distinction was made more informally by dividing pensioners between those in receipt of a monthly allowance and those who were relieved on a weekly basis. The lowest strand in the hierarchy of relief came in the form of casual payments - one-off doles of a few pence or a shilling proffered in response to personal plea to the overseer.

In the 1730s at St Dionis Backchurch, the accounts make these division explicit, dividing all expenditure between the relevant headings:

- Cash paid Weekly Pentioners

- Cash paid Quarterly Pentioners

- Cash paid & Casual Poor

- To Yearly Gifts

- To The Gift on St Thomas's Day

Of course direct cash payments and doles formed only a portion of the relief provided, and the accounts tend to de-emphasise relief in the form of clothing and shoes, rent payments and education; of medical costs, transport and aid to retrieve tools from pawn, or the wherewithal to set out on a new career.

The experience of the poor themselves, and the level of relief they could expect is discussed under a different heading: The Poor. But from the parish's perspective, the relief they provided encompassed an almost unlimited series of categories, and was divided amongst a precisely graded body of paupers. And if the parish implemented these divisions with care, it is also clear that the poor themselves took them to heart. One of the great complaints voiced on the establishment of parish workhouses is that they tended to undercut the distinction between a decayed householder and a casual beggar; that in the words of the author of The Workhouse Cruelty (1731), they allowed:

The Rise of the Parish Employee

In a small rural community all parish administration would be undertaken by annual officers drawn from local householders, but with annual expenses running into hundreds or thousands of pounds, most London parishes found they need professional support. The rise of professional parish employees changed the nature of the relationship between the parish and the pauper. In general, it had the effect of creating an ever wider gulf between the parish worthies who sat in the vestry, and the paupers beseeching support at the workhouse door (rather than in the overseers' front room). The rise of the parish professional also substantially improved the standard of record keeping and financial control.

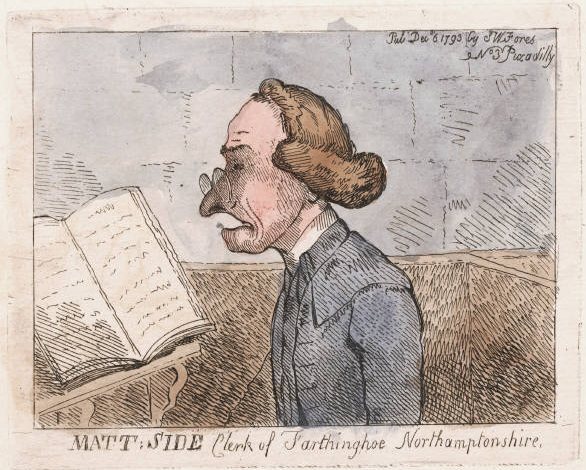

Matt: Side Clerk of Farthinghoe Northamptonshire, 1795. Lewis Walpole Library, 793.12.6.1. © The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

Matt: Side Clerk of Farthinghoe Northamptonshire, 1795. Lewis Walpole Library, 793.12.6.1. © The Lewis Walpole Library, Yale University.

The most common form of paid parish employee, after the minister, was the parish clerk. The clerk's position normally attracted a salary of twenty or thirty pounds per annum, but in the wealthy parishes of Westminster, could earn substantially more than this. Because the position continued year to year, the clerk rapidly became a figure of real authority - able to cite precedent where annual officers floundered. In the right circumstances it could also be a job for life. Robert Chinnow, for instance, first appears in the records of St Clement Danes in 1719, and retained the role of parish clerk until his death in 1744, when he was replaced by his son, William Chinnow. William served in the same capacity until his own death in 1767, when he was in turn replaced by his son William Chinnow the Younger.

Of more direct concern to the parish poor was the role of workhouse master. A large parish workhouse could itself employ a dozen servants, and these arrangements are described under workhouse conditions, but the role of master and to some extent mistress carried with it a level of authority and responsibility that brought real power. And again, it was a variety of power that left the poor at a distinct disadvantage. They could no longer use the claims of a life shared in the same parish with the overseer, and instead had to manipulate a system of rules and regulations.

Equally important, the parish nurse, apothecary and surgeon, watch house keeper, and night watchmen all grew in number and importance. Each new role required new rules and regulations, and increasingly drove a professional wedge between the recipients of relief and the vestrymen and ratepayers of the parish.

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keywords Casual Pauper:

Lives using the keyword Pensioner:

Introductory Reading

- Hindle, Steve. On the Parish?: The Micro-Politics of Poor Relief in Rural England, c.1550-1750. Oxford, 2004.

- Hitchcock, Tim. Down and Out in Eighteenth-Century London. 2004.

- Neate, Alan Robert. The St Marylebone Workhouse and Institution, 1730-1965. Rev. edn, 2003.

- Slack, Paul. The English Poor Law, 1531-1782 (Studies in Economic and Social History). Basingstoke, 1990.

- Slack, Paul. From Reformation to Improvement: Public Welfare in Early Modern England. Oxford, 1999.

- Webb, Beatrice and Webb Sidney. English Local Government: English Poor Law History: Part 1. The Old Poor Law. 1927.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 William Maitland, The History of London from its Foundations by the Romans to the Present Time (1739). See p. 718 for information relating to St Clement Danes and p. 391 for St Botolph Aldgate. For the St Clement Danes act of parliament see 4 George III c.55. ⇑

2 See Richard Burn, The Justice of the Peace, and Parish Officer (14th edn, 1780), volume 1, pp. 443-445, volume 3, pp. 586-580. ⇑

3 7 George III c.39. ⇑

4 Steve Hindle, On the Parish? The Micro-Politics of Poor Relief in Rural England, c.1550-1750 (Oxford, 2004), ch. 4. See also Ilana Krausman Ben-Amos, The Culture of Giving: Informal Support and Gift-Exchange in Early Modern England (Cambridge, 2008), pp. 87-90, 92-4. ⇑

5 The Workhouse Cruelty, Workhouses turn'd Gaols, And Gaolers Executioners (1731). British Library, 816 m.9 (781). ⇑