Chapter 7.

The state in chaos: 1776–1789

Introduction

During the 1760s and early 1770s, plebeian Londoners nursed an accumulating sense of grievance. Innovations in policing and prosecution placed those suspected of crimes at a growing disadvantage, while new poor relief policies created an ever widening chasm between parish worthies and the dependent poor. Yet through both legal and illegal means, individually and collectively, plebeian Londoners had developed and refined effective tactics for challenging authority. In this febrile context, war with America broke out in 1775, a war whose far-reaching consequences would include not only an ideological crisis over the state of English liberties but also a fundamental renegotiation of social policy in the metropolis. The interruption of criminal transportation caused unprecedented chaos in the penal system and the creation of Britain’s first mass prison population. The hardships suffered by prisoners held for years in buildings designed for short-term incarceration, or in rotting hulks on a stinking Thames, laid the foundations for keenly felt grievances. Thousands of Londoners experienced, for the first time, the pressured boredom of long days spent in powerless proximity with people just like themselves: marked, like the vast majority of criminals, by their youth, poverty and ill-luck. In the process, and despite relatively favourable climatic and economic conditions (except following demobilisation in 1783), new patterns of resistance developed.

This chapter describes these new communities of resistance, solidified through long-term imprisonment and shared suffering following 1776; communities created at a time of intense political debate. It argues that it was the new-lived, and by 1780 widely shared, experience of mass imprisonment that transformed the Gordon Riots from an anti-Catholic protest into an organised proto-revolutionary series of attacks on the prisons of London. The origins of the reconfigured system of criminal justice and poor relief that followed can be found most fully in the experience of plebeian men and women forced into desperate dialogue with judges and turnkeys, overseers and churchwardens.

Punishment in crisis

The suspension of transportation, caused by the outbreak of war with America in 1775, followed the growth of elite dissatisfaction with transportation over the previous decade. It nonetheless created an unprecedented penal crisis. A criminal justice system that for sixty years had shipped hundreds of London felons to North America each year was suddenly confronted by the need to guard and care for a population of convicts that grew month by month, with each meeting of the courts. And while some of the prisons which held them had been rebuilt or remodelled, all prisons remained inadequate to the task of securely holding large bodies of prisoners. The scale of the problem can be seen in the fact that in the previous decade, transportation had accounted for two-thirds of all sentences at the Old Bailey, amounting to an average of 263 convicts a year.1 The prisons quickly became overcrowded with convicts awaiting transportation, and new (it was hoped, temporary) arrangements had to be made. In justifying this to Edmund Burke in March 1776, the penal reformer William Eden said, ‘The fact is, our prisons are full, and we have no way at present to dispose of the convicts.’2 This overcrowding prompted the passage of the ‘Hulks Act’ in 1776, which authorised alternative punishments for those sentenced to transportation and currently languishing in prison.3 Male convicts were to be put to hard labour ‘improving the navigation of the Thames’, while female convicts, and men incapable of performing such physical work, were to be committed to houses of correction. The place where the men ordered to work on the Thames were to be incarcerated was not specified, but Duncan Campbell, the man awarded this contract (who had formerly contracted to transport convicts to America) decided to house them in disused ships, which became known as the hulks. The first two ships, the Justicia and the Censor, took on their first prisoners in August 1776. They too soon became crowded: Campbell reported in April 1778 that there were 370 men on board these vessels; the following year this had increased to 510, divided almost equally between them.4

Conditions on the hulks were intentionally poor. Despite the fact the prisoners were put to gruelling labour shifting gravel and soil on the banks of the Thames, the Act specified that the convicts were to be ‘fed and sustained with bread and any coarse or inferior food, and water or small beer’, and nothing else.5 When combined with the crowded conditions, the fact that some of the prisoners were already infected with gaol fever when they arrived, and the absence of a surgeon or apothecary on board ship, this poor nutrition led to frequent illness and death. In the first twenty months, over a quarter of the prisoners died (176 of 632); and 138 more perished in the following year.6 This high mortality attracted widespread criticism. When the prison reformer John Howard visited the convicts on the Justicia in October 1776, ‘he took two walks round them, and looked in the face of every individual person, and saw by their sickly looks, that some mismanagement was among them’. He inspected the food and reported that ‘all the biscuits were mouldy and green on both sides’, and noted that the convicts had no bedding. The resulting ‘depression of the spirits’ among the prisoners was frequently remarked upon by visitors to the ships, and Dodo Ecken, an assistant surgeon, reported ‘that he had known eight or ten of the convicts die merely of lowness of spirits’.7

Conditions improved in subsequent years, partly owing to pressure from the prisoners, who were able to communicate their grievances to visiting magistrates and doctors. Their escapes and mutinies also played a part. Campbell reported that following a mutiny of the prisoners in 1778 he increased the allowance of bread and other foodstuffs for the prisoners such that, he claimed, ‘the provisions allowed to the convicts were… better than laboring men usually had’.8 In order to address the problem of morale, pardons were offered to well-behaved prisoners, and in 1779 sick prisoners were removed to a separate hospital ship. But the hulks remained crowded, mortality rates remained high and the prisoners remained rebellious.

. © Trustees of the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich.](Images/fig7_1.jpg)

Figure 7.1: Carver & Bowles (publishers), ‘A view near Woolwich in Kent, shewing the Employment of the convicts from the Hulks’ (1779). NMG PAJ0774. © Trustees of the National Maritime Museum at Greenwich.

Stewart Erskine, the captain of the hulks, claimed that prisoners from the country were more likely to be ‘very much dejected’ than the London felons, and this makes sense. Prisoners from London had more friends, both on the hulks and outside, and were probably more able to organise resistance.9 When on board prisoners were confined below deck in large undivided spaces, while the small number of guards stayed above, giving prisoners plenty of opportunities to plot escapes.10 Left to their own devices, and experiencing horrific conditions, this is just what they did. There were four mass escapes in the first few months of the hulks, at least one more in 1777, and a mutiny in September 1778 called the ‘insurrection’ by contemporaries. Perhaps consciously following in the tradition of riverside labour unrest last seen ten years earlier, about 150 prisoners working on the shore of the Thames armed themselves and attempted to force their way past the guards to escape. In the ensuing battle two were killed and seven or eight more were wounded.11 While none got away, Treasury papers indicate that between 1778 and 1780 forty prisoners did manage to escape.12 Although many were not recaptured, between 1776 and 1780 seventeen escapees were put on trial at the Old Bailey, including one, John White alias Stephen Broadstreet , who escaped twice, in 1777 and 1780, and who would later be active in the Gordon Riots. In their defence, the prisoners justified their actions by the terrible conditions on board.13 Thomas Farmer , who escaped on 7 November 1776, pleaded with the court to sentence him to service in the navy rather than return him to the hulks, since he was ‘afraid I shall be cruelly used on board this ship again’.14 More explicitly, Michael Swift , convicted of shooting at boatswain Charles West during the ‘insurrection’, justified his actions by telling the court that ‘The usage of the place is enough to make any man try to escape; they not only starve them, but murther them’.15

The interconnections between the escapees testify to the development of a culture of resistance on the hulks. Charles Drake, described in the Public Advertiser as an American by birth, who had a long criminal record and had escaped from one of the hulks in December 1777, shared experiences with, and probably knew, three other escapees.16 When he was first convicted of the theft of a silver watch in April 1776, he, along with several other prisoners convicted of grand larceny, was sent back to Newgate to remain until the May sessions, while the government worked out what to do with prisoners who would previously have been sentenced to transportation. One of the prisoners who shared that experience, and who was also sentenced to branding in May, was Thomas Farmer, who, following another conviction which resulted in his commitment to the hulks, escaped in November of the same year.17 Michael Swift, who was sentenced along with Drake to the hulks in January 1777, was also a past and future escapee.18 He had escaped from Clerkenwell house of correction in October 1776, and would later escape from the hulks in June 1778. Soon recaptured, his rebellious mood was no doubt contagious; four months later, as noted, he was a participant in the ‘insurrection’.

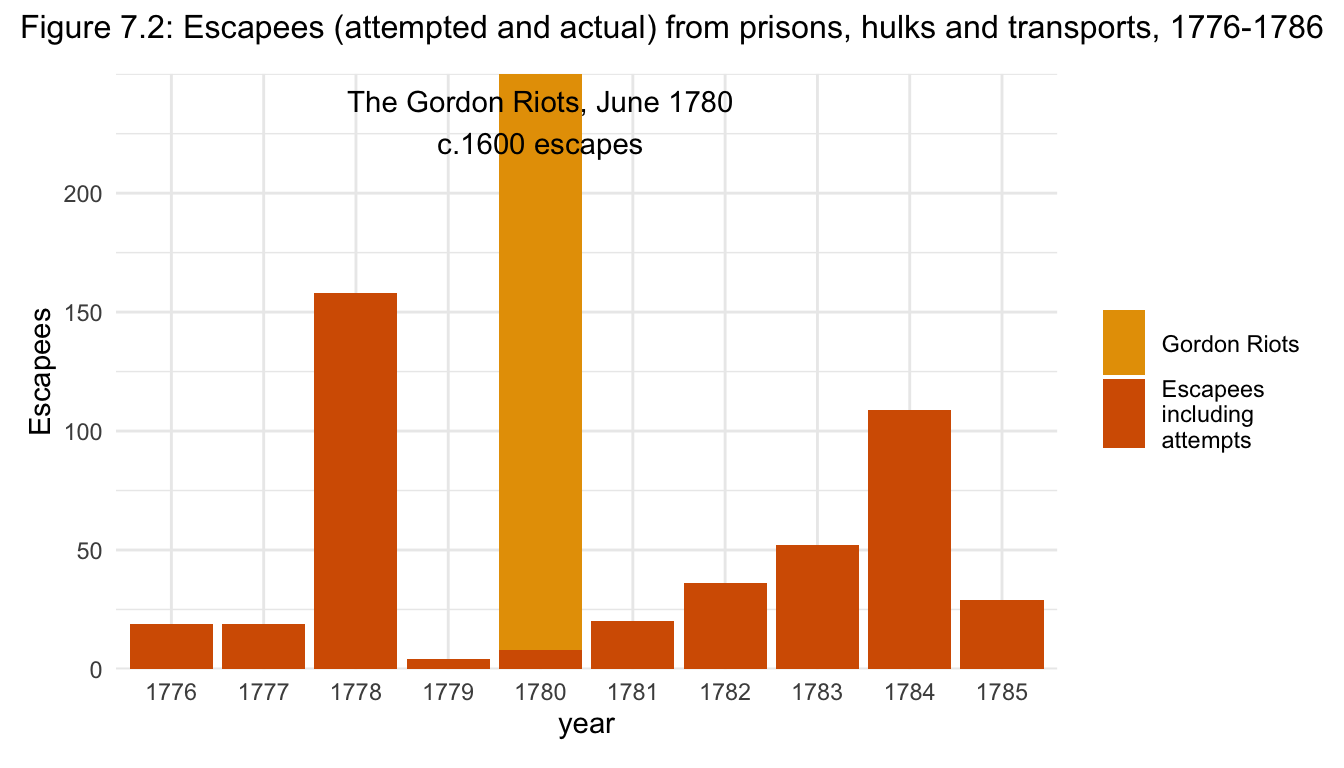

Figure 7.2: Escapees (attempted and actual) from prisons, hulks and transports, 1776-1786.

Note: This database and graph do not include reports of ‘several persons’ escaped from Newgate prison in 1778; ‘divers prisoners’ from New Prison twice in 1781; and ‘several’ escapees from Newgate prison in 1782. No systematic record of escapes survives, and these figures, derived from a wide range of sources, should be considered as indicating a minimum.

Online dataset: Escapes 1776-1786 (xlsx)

Figure 7.3 (a): ‘Here lies John Jones, doubel ironed for attempting to break out of Newgate, 1776’. ©Tim Millet.

Figure 7.3 (b): ‘Here lies John Jones, died June 19 1776’. ©Tim Millet.

While the hulks would continue to be used into the nineteenth century to meet the continuing need for extra prison accommodation for those awaiting transportation, this convict resistance was one of the reasons, in addition to disease, why the authorities rapidly lost faith in them as anything other than an unsatisfactory stopgap and sought to limit their use.19 In 1779 the Penitentiary Act restricted the power to sentence offenders to the hulks to judges at the Old Bailey and the assize courts. The Middlesex justices, who had sentenced 86 prisoners to the hulks between July 1776 and February 1779, mostly for petty larceny, lost this option.20 Felons also became less likely to be committed there, as the average population of the hulks, which peaked at 508 in 1779, declined steadily to only 199 in 1783.21 The last convict sentenced directly to the hulks at the Old Bailey in the 1780s was Charles Manning, convicted of highway robbery in April 1784.22 The House of Commons committee which met in the spring of 1779 to consider the fate of convicts previously transported noted recent improvements to the hulks, but recommended the resumption of transportation for the most serious offenders as soon as it became feasible, and imprisonment at hard labour for ‘the class of convicts heretofore liable to transportation’ who were not strong enough for ‘any severer punishment’. Having marked the many deficiencies of the hulks, the committee recommended that these convicts should instead be kept in ‘solitary confinement … [with] well-regulated labour, and instruction’; essentially in a new form of prison – a penitentiary.23

Even when the hulks were still an acceptable penal option, not all convicts could be accommodated on them. In addition to female convicts and the men deemed incapable of hard physical work, both of whom were sentenced to houses of correction, many other men were incarcerated in London’s prisons simply because the hulks did not have space for them. The same House of Commons committee reported that in April 1779 243 convicts were incarcerated in the city’s prisons, including 84 in Newgate, 114 in the Clerkenwell house of correction and 10 in New Prison. When Richard Akerman, keeper of Newgate, was asked ‘how it came to pass that many who were sentenced to the hulks remained in Newgate’, he answered, ‘there was no room on board the vessels to receive them’.24

When these prisoners were added to those awaiting trial and convicts sentenced to terms of imprisonment, the resulting overcrowding led to conditions not dissimilar to those found on the hulks. Never before had London’s prisons been forced to accommodate so many long-term prisoners, placing new demands on their keepers. In October 1777 Thomas Gibbs, surgeon and apothecary to both New Prison and the house of correction at Clerkenwell, petitioned the Middlesex justices, asking for an increase in his salary owing to the higher level of medical care required in both prisons. Referring to the prisoners who ‘have been sentenced to imprisonment in the said jails’, he claimed that many came in ‘diseased and frequently continue so from their poverty and long confinement not to mention the many infected prisoners who from time to time are sent to remain in these jails from Newgate’.25 In Newgate itself, Akerman found the same ‘dejection of spirits among the prisoners’ which others had found on the hulks, and he reported that ‘many had died broken-hearted’.26

There were, however, two important differences between the hulks and the prisons. First, those on the hulks had to subsist on the food provided, while those in the prisons relied primarily on food and drink brought in by friends and family, supplemented by prison charities. Duncan Campbell reported that initially he had allowed friends to bring provisions to the convicts on the hulks, but he was forced to forbid the practice ‘as they conveyed saws and other instruments for their escape’.27 Thus, the second difference was that the prisoners incarcerated on land were able to receive frequent visitors, a practice made possible by the relatively lax visiting rules in the still unreformed prisons. Not only might tools be smuggled in to assist with a break-out, but visitors also brought ideas and messages. In Newgate, as Akerman reported, ‘all the male prisoners, accused of felonies and misdemeanours, associated together in the day times’ (as did female prisoners, but in a separate yard).28 London prisoners, particularly the convicts incarcerated for years as the war dragged on, had plenty of time, opportunity and grievances about prison conditions to encourage them to conspire in pursuit of escapes and insurrections. As a result the numbers of prison escapes rose to a new level.

Between 1776 and the Gordon Riots in June 1780, with their wholesale release of up to 1,600 prisoners, there were group escapes from the Clerkenwell house of correction (7 prisoners, including Michael Swift in October 1776), and New Prison (despite the fact it had been significantly rebuilt only a few years earlier), where ‘several persons’ escaped ‘by cutting their way through the walls’ of the prison in July 1778.29 There were also individual escapes from Wood Street Compter, the house of correction at Clerkenwell, and New Prison. Edward Hall, keeper of the house of correction, made the connection explicit between the presence of convicted felons in his prison and these escapes, telling a committee of justices ‘he is thence more liable to escapes’.30 While the new buildings of Newgate prison proved almost invulnerable, it witnessed a substantial riot in August 1777, when a group of prisoners led by Patrick Madan caused considerable damage: ‘all the windows were broke, and iron casements thrown into the yard, together with innumerable brickbats which had been broke from the inside of their wards; and one of the other wards began to be demolished, in which business they continued all night’.31 The prisoners were encouraged by ‘the famous Miss West’, who repeatedly shouted ‘Go it lads, go it, dash away, don’t spare them! Liberty! Liberty! Liberty!’. Once order was restored, the prisoners justified their actions by saying ‘the length of their imprisonment, some of them being for seven years, and others five years, together with their poverty, had made them desperate’.32

A simple physical marker of the newly rebellious mood of the prison population can be found in the existence of ‘convict love tokens’. These were fashioned from coins, pounded flat and carved with a simple message, usually recording the date a prisoner was convicted and their name, and a plea that they should be remembered by loved ones. One of the earliest known examples of these mementos is dated 1776 and commemorates John Jones, ‘doubel ironed for attempting to break out of Newgate’ (figure 7.3).33 Over the course of the next decade, these tokens became a physical reminder of the chasm that imprisonment, and later transportation to New South Wales, created between those convicted of crime and the communities which supported them. That they were made by hammering smooth a coin decorated with the face of the king and all the symbols of state power simply added significance to these love tokens as a marker of popular hostility.34

The overcrowding and security challenges posed by the presence of so many convicts after the suspension of transportation prompted the authorities to make changes to the Clerkenwell house of correction and New Prison.35 In 1777 iron spikes were ordered to be fitted to the walls of the house of correction, to render it ‘more secure against the attempts of the convicts therein confined’, and the following year it was recommended that all the walls of the wards in New Prison be ‘secured with iron hoops and sheathed with oak… in order to prevent the possibility of an escape in the future’.36 Other improvements addressed the unsanitary conditions which the overcrowding exacerbated: ‘air holes lights or windows’ were cut in the walls of the women’s gallery of the house of correction to improve circulation and a bathing tub was provided for the female prisoners. In New Prison a separate ward was created to accommodate sick prisoners.37

Nevertheless, conditions remained dire, and it is likely that the convicts who served long terms, often at hard labour, both on the hulks and in the prisons, accumulated deep feelings of resentment which were communicated to their families and friends and no doubt remained even after they were discharged. This resentment flared into active and violent resistance to the institutions of policing and punishment in June 1780.

The Gordon Riots

The Gordon Riots erupted on a hot Friday, 2 June 1780, and within a week at least 285 men and women were dead, and a further 173 seriously injured.38 Some estimates put the dead and wounded as high as 700.39 The damage wreaked on the fabric of the city in a full week of rioting is estimated to have run to £200,000, with thirty-two private homes destroyed as well as numerous businesses and public buildings.40 Although several detailed narratives are available, the events of that week have not been effectively integrated into a larger analysis of the evolution of plebeian resistance to criminal justice.41

Undoubtedly the immediate trigger for the riots was the parliamentary agitation associated with Lord George Gordon, who, as leader of the Protestant Association, sought the repeal of the Catholic Relief Act of 1778.42 This Act ameliorated the laws restricting the legal position of Catholics in England, and although it had faced little active opposition in parliament when it was initially passed, it rapidly became the focus of an extensive extra-parliamentary campaign to have it repealed. An effective measure of the kind of respectable support the Protestant Association attracted is the high-profile participation of men such as William Payne, the ‘Protestant Carpenter’ and an active figure in the reformation of manners campaign of 1757–63.43 Payne expressed strongly anti-Catholic views throughout his life, in conjunction with an equally strong commitment to a rigid social order, based on the preservation of a coherent Protestant community. According to Gordon, it was Payne who insisted on marching en masse to present the petition for repeal to parliament, who led the City of London division and who was identified as inciting the mob outside parliament itself.44 That Gordon could garner some 100,000 signatures to his ‘monster petition’, and marshal between 40,000 and 60,000 people to attend, in military formation, his public meeting on St George’s Fields, reflects the extent to which he had touched a significant nerve among a wider populace, made up of many of the same men who served as overseers and constables, vestrymen and clerks, and the householders who had contested the powers of the select vestries. But the events that followed the delivery of that monster petition helped to expose the divisions between Payne’s world of parish feasts, seasonal charity and moral policing and that of an emerging self-consciousness among criminals and the poor.

The afternoon of Friday 2 June was given over to a heated debate in parliament, with Lord Gordon attempting to use the milling crowds of excitable Associationers outside to drive through the repeal of the Act. But as parliament prevaricated and delayed, finally adjourning its decision to the following Tuesday, and as a hot day turned into a torrid evening, events rapidly moved beyond the control of Gordon and his associates. By evening, Lords Hillsborough, Stormont and Townsend found themselves attacked by a crowd that was rapidly becoming a mob; their wigs pulled from their heads, ‘hair flowing on their shoulders’, they were forced to flee down side streets in hackney coaches and sedan chairs.45 The wheels were taken off the carriage belonging to the Bishop of Lincoln, Lord Mansfield was forced to run from his coach as the mob smashed its windows, and the Archbishop of York was cornered in Parliament Street and forced to chant ‘No Popery!’ in ‘a pitiable and enfeebled voice’.46 Gordon attempted to calm the crowds, but it was only at eleven in the evening that a troop of guards was able to free the politicians who remained in parliament.

That evening the rioting began in earnest, with the firing of the Catholic chapel belonging to the Sardinian ambassador in Lincoln’s Inn Fields, and later the chapel attached to the Bavarian embassy in Warwick Street. Thirteen arrests were made that night by troops arriving late on the scene, following ‘much scuffling’ in which several people were slightly wounded by the bayonets wielded by the soldiers.47 However, while the anti-Catholic objectives of these early riotous events are self-evident, the beginnings of a new focus on attacking the institutions of criminal justice can be found. Outside the Sardinian Chapel, Sampson Rainsforth,48 a man closely associated with Bow Street and its policing of Westminster, and who had testified against some of the arrested rioters, was spotted, and the mob yelled ‘Damn him! He … is the late High Constable [of Westminster]; knock him on his head’.49 In that moment, the riots began to turn from a Protestant outcry voiced by respectable householders into an assault on the judicial system. ‘Anti-popery’ was a shibboleth that could unite Londoners of all social classes, drawing on 250 years of shared politics.50 Policing and criminal justice, in contrast, divided communities along very different lines.

The composition of the crowds that filled London’s streets over the ensuing week and the motives of the rioters have been hotly contested ever since. George Rudé, on the basis of a detailed analysis of those prosecuted following the riots, agreed with Charles Dickens, who in Barnaby Rudge characterised the rioters as for the most part ‘sober workmen’ and apprentices.51 If we take the example of William Winterbotham, one of the few people who admitted to participating in the riots of his own volition, this description seems apt. A seventeen-year old apprentice silversmith from Aldgate, given to both ‘evil ways’ and ‘much false zeal’, Winterbotham admitted he had ‘entered warmly into the … senseless cry of “No Popery”’.52 However, the list of people eventually tried as a result of the riots also includes the ragged edge of London society: beggars and prostitutes, casual labourers, and Black refugees from the American Revolution.53 Overall, it is clear that individual riots drew their personnel from all the varied communities of London. For the most part, people rioted on their doorsteps. Their motivations were similarly mixed, local and constantly changing. Certainly anti-Catholicism remained important, and attacks on Catholic houses and institutions can be found throughout – though as Rudé has demonstrated these were focused on rich Catholics to the exclusion of the poor majority of Irish Catholic immigrants.54 But there were also many, to follow James Gillray ’s assessment made during the riots and published on 9 June, who had ulterior motives:

Tho’ He says he’s a Protestant Look at the Print

The Face and the Bludgeon will give you a hint.

Religion he cries in hopes to deceive.

While his practice is only to burn and to thieve.55

A constant and insistent strand discernible throughout the course of the riots was a powerful hostility towards criminal justice and its institutions, and not simply those which contained prisoners arrested in the riots. Two days of relative calm followed the events of Friday the 2nd, but the riots caught flame on Monday, when Sampson Rainsforth’s house in Clare Street was attacked and pulled down, causing £624 worth of damage. On Tuesday Justice William Hyde ‘s house in St Martin’s Street was attacked, with the eventual cost of the night’s mayhem amounting to £2,062. Hyde was a prominent justice and had read the Riot Act in Palace Yard the preceding Friday. This anti-criminal justice focus rose to a new pitch of concerted activity with attacks on the house of the Lord Chief Justice, Lord Mansfield, in Bloomsbury Square, where over £5,700 worth of damage was caused in a few short hours, before taking in the administrative epicentre of new policing, John Fielding’s house in Bow Street.56 In addition to causing over £1,000 worth of damage to the fabric of the house, the rioters were also careful to destroy Fielding’s registers of known and suspected offenders.57 By contrast, at £472, the cost of the damage inflicted on the Bavarian Chapel in Golden Square ran to less than half of that inflicted on Bow Street.58 Rioters seeking revenge also totally destroyed the Bethnal Green house of Justice David Wilmot, who had been active in prosecuting the ’cutters’ during the weavers’ disputes a decade earlier. The next day John Gamble was heard bragging that the rioters had, ‘done Davy … they had done the Doctor on the green’.59

, 2 Jan. 2014. ©Trustees of the Lewis Walpole Library.](Images/fig7_4.jpg)

Figure 7.4 James Gillray, No Popery, Or Newgate Reformer (1780). Lewis Walpole Library, 780.06.09.01+, 2 Jan. 2014. ©Trustees of the Lewis Walpole Library.

Attempts to rescue rioters previously arrested were a traditional component of many eighteenth-century riots, as were attacks on the houses of those who attempted to suppress disorder, but by Tuesday only three rioters remained in custody – all in Newgate – and John Fielding, who was ill, was not directly involved in suppressing the riots. The crowd was wreaking revenge on a system of justice whose policies of arrest and prosecution amounted to a ‘transporting and hanging system of police’. Despite the fact that Bow Street had held some of the arrested prisoners, the destruction of Fielding’s records and the attacks on the houses of other justices and Lord Mansfield cannot be seen as simple acts of rescue, but instead took on the character of revenge. The high level of destruction (not looting) inflicted on them – amounting to over £10,000 in total – reflects a distinctive and different pattern of behaviour from that found in typical London riots.60

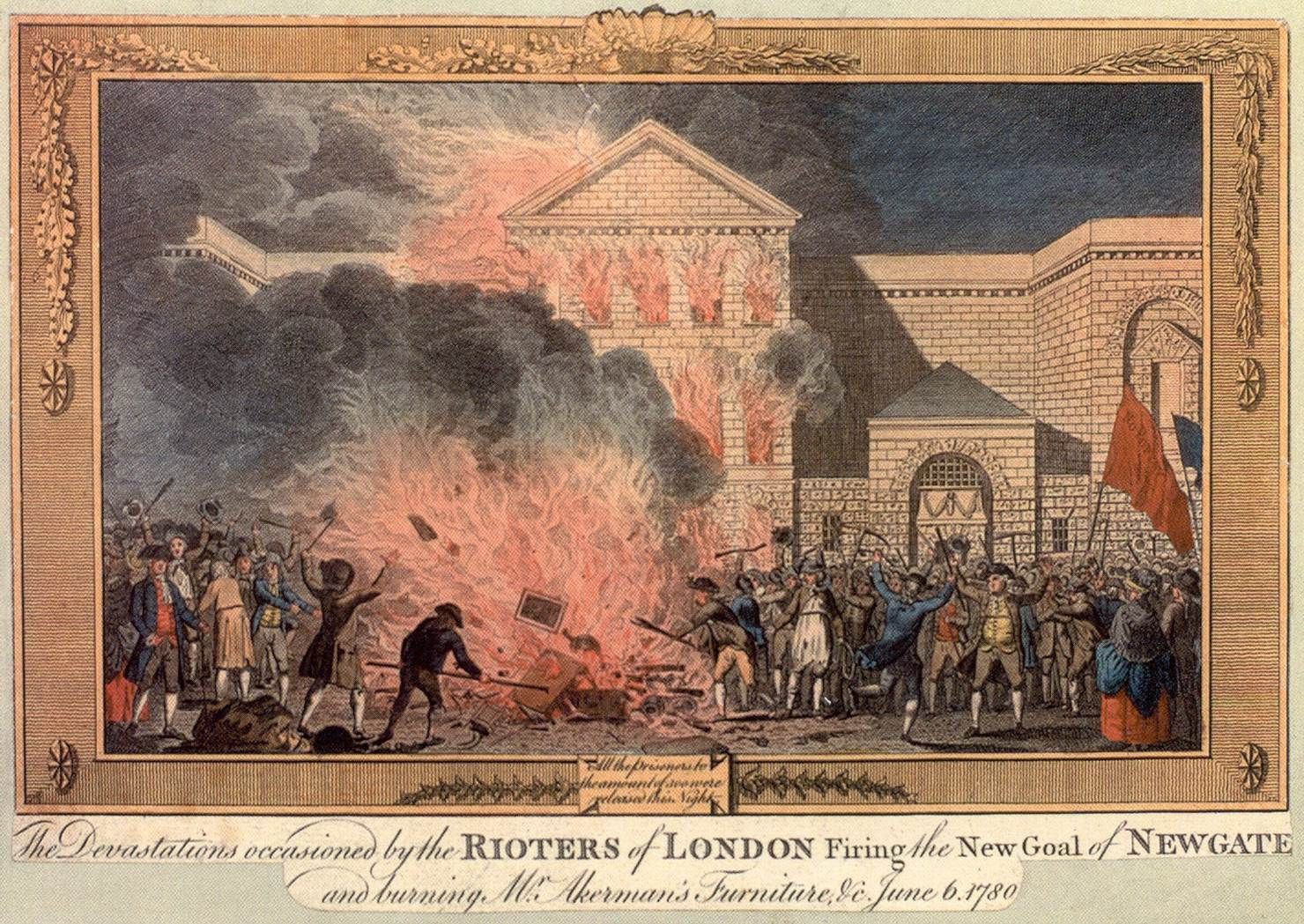

Figure 7.5: The devastations occasioned by the rioters of London firing the new goal of Newgate … June 6, 1780. © London Metropolitan Archives, ref. SC/GL/PR/446/OLD/2/q8038930.

It was only on Tuesday, five days into the riots, that we come to the famous set piece at their heart, with the attack on Newgate prison itself. According to one witness, the mob was led by James Jackson, a sailor recently returned from sea:

he cried out ‘Newgate, a-hoy’. That was about six o’clock, as near as I can recollect. He went down Orange Street coming towards Newgate. Great numbers of the mob followed him.61

It sometimes seems as if half of London was either in the crowd before Newgate or looking down on the scene from the windows above. However, what is beyond doubt is the destructive fury unleashed. The fabric of the newly completed prison was almost entirely destroyed, and 117 prisoners, from petty thieves to murderers, were set loose on the streets.62 In the words of the clerk of the works:

the new Gaol of Newgate and … the chapel and keeper’s house etc thereto belonging … were totally destroyed and several of the external parts considerably damaged by fire, the loss sustained by this means … could not be made good for a less sum than £30,000.

The prison would not be fully operational again until July 1784, more than four years later.63

Fanny Burney, watching from the roof tops on Tuesday evening, identified four separate major conflagrations, all associated with criminal justice: ‘Our square was light as day by the bonfire from the contents of Justice Hyde ’s house …; on the other side we saw flames ascending from Newgate, a fire in Covent Garden which proved to be Justice Fielding’s house, and another in Bloomsbury Square which was at Lord Mansfield’s.’64 And this was just the start. The attack on Newgate was quickly followed by attacks on King’s Bench and Fleet prisons, New Prison and the house of correction at Clerkenwell. ‘The cause’, in the words of Thomas Haycock, sentenced to hang for his role in the destruction of Justice Hyde’s house and Newgate prison, was not religion, or even the courts, but to ensure that ‘there should not be a prison standing … in London’.65

One after another the prisons fell, or their keepers meekly opened their gates in hopes of preserving their private carceral fiefdoms. Contemporaries began to fear that it was not simply the prisons that were under assault but also the law itself. The barristers and students of the Inns of Court certainly felt themselves likely objects of attack. John Grimston reported to his friends in Yorkshire what he purported to be the common knowledge that ‘there was a plan laid to burn all the Law Societies’. And indeed, the residents of the Inns were issued government arms with which to protect themselves, and the Temple and Barnard’s Inn were actually assaulted.66 Tellingly, the destructive force of the riots was also remarkably selective. In contrast to the extensive destruction visited on Bow Street and Newgate, the Sessions House at the Old Bailey (next door to Newgate, and home of the jury trial), while attacked, was relatively little damaged, with only some of the furnishings destroyed. Repairs cost just under £170, and ironically the building was sufficiently intact to host the trials of the first rioters on 28 June.67 On the day Newgate was attacked, at least one rioter also tried to rally the crowd for an attack on the nearby Bridewell (one of the oldest and most traditional of London’s prisons), calling, ‘Now my lads, for Bridewell’, but no one chose to follow him.68

We should not understate the profound significance of these assaults on the prisons, or the extent to which they heralded a desperate, if inchoate, revolutionary moment. The Bank of England came under sustained attack in the twenty-four hours following the burning of Newgate, and was only preserved from sacking by brute military force. Lord Gordon attempted and failed to convince the mob outside the Bank to desist – a clear measure of the profound distance between the crowds of the previous Friday and those assembled before the Bank. More tellingly, John Wilkes, hero of the mob in the 1760s but now ex-Lord Mayor of London, resorted to arms. Acting in his capacity as a Buckinghamshire militiaman, in combination with the 534 soldiers stationed at the Bank under the command of Lt Col. Thomas Twisleton, he ‘Fired 6 or 7 times on the rioters at the end of the Bank … Killed two rioters directly opposite to the great gate of the Bank; several others in Pig Street and Cheapside.’69 The battle of Fleet Street alone resulted in sixty dead or wounded rioters shot at close range – though the actual number may have been much higher, as contemporaries believed that many of the dead were unceremoniously pitched into the Thames to save them from being identified.70 A simple measure of the sense of crisis induced by the rioters, and the extent to which their objectives extended beyond the religious policies of the state, is contained in the list of buildings which desperately sought military defenders over these days. Besides the prisons and the Bank of England, they included the South Sea Company, East India Company, Excise Office and Customs House, Navy Pay Office, Victualing Office, Freemasons’ Hall, and Coutts’, Thelusson’s and Drummond’s Banks.71 These institutions represented a broad range of power and authority. It is worth noting that not a single workhouse, hospital or parish church was attacked.

The riots were finally suppressed through concerted military action on Thursday 8 June. By this time three interwoven changes had occurred. First, the refusal of the Lord Mayor and many of the justices of peace of London and Middlesex to sanction the direct use of military force against the rioters, arising from their traditional conception of law and order as best achieved through negotiation and mediation (and previously seen in their unwillingness to have executions policed by the military), forced the government to step in. This fundamentally changed the relationship between civilian government and the military. On Wednesday the 8th, the Privy Council passed a general order sanctioning the use of military force without the prior consent of a local justice, and vested the management of the military response to the riots in the hands of Lord Amherst as commander-in-chief. In the process the Council effectively undermined the role of justices of the peace, who even following the passage of the Riot Act had been a civilian check on the use of troops against rioters.72

Second, the parish worthies who had signed the petition, who saw in a common defence of a confessional Protestant community a defence of their own liberties, were made to look at their fellow Londoners and found in the rioters harbingers of disorder and chaos, rather than co-religionists and loyal subjects. During the riots themselves, and in the months and years that followed, inhabitants’ associations and parish patrols were organised to police the streets and to ensure that the parish community was protected against its own less respectable members.73 By 27 June, William Payne, who began the month leading the crowd outside parliament, was writing to the Lord Mayor setting out plans for the recapture of the prisoners released on the storming of Newgate.74

And finally, the riots both reflected and contributed to a transformation in the attitudes of the poor. Changes to the systems of police and punishment were a motive force behind the unprecedented scale of the riots. The anger that was unleashed was then exacerbated by the response of the judicial authorities to the events of that June, ensuring that the same motives and agenda that stirred the rioters would continue to influence plebeian actions and attitudes.

The aftermath

Now back in control, the authorities were quick to exact retribution. Of the 450 rioters who were arrested, 160 would eventually appear at trial.75 Of these men and women, mainly social outcasts offered up by their own communities as exemplary culprits, 62 received sentences of death, of whom 26 were eventually hanged. In the long weeks of July and early August, the neighbourhoods that had seen the riots’ most destructive violence played host to executions designed both to allow plebeian Londoners to witness the retribution meted out by their social superiors and to ensure that not so many bodies swung from any single gibbet that public tolerance was stretched beyond endurance.76 Policed by the new parish associations (the uniformed military assiduously kept out of sight, if not out of reach), these executions drew crowds of up to 12,000 people, and were marked by a quiet solemnity.

In the same months London took on the feel of a military encampment. While troops stayed away from the executions, they were stationed at the prisons and courts, and the parks were filled with over 10,000 soldiers. The overt military presence was gradually withdrawn and preference was given to parish associations and local militia, who radically increased the personnel available for police duties; but by the autumn, as the last of the rioters were hanged and the military were increasingly confined to barracks, a new dispensation emerged. Respectable Londoners had become more distrustful of their social inferiors, while a stronger sense of opposition to authority could be found among prisoners and defendants.

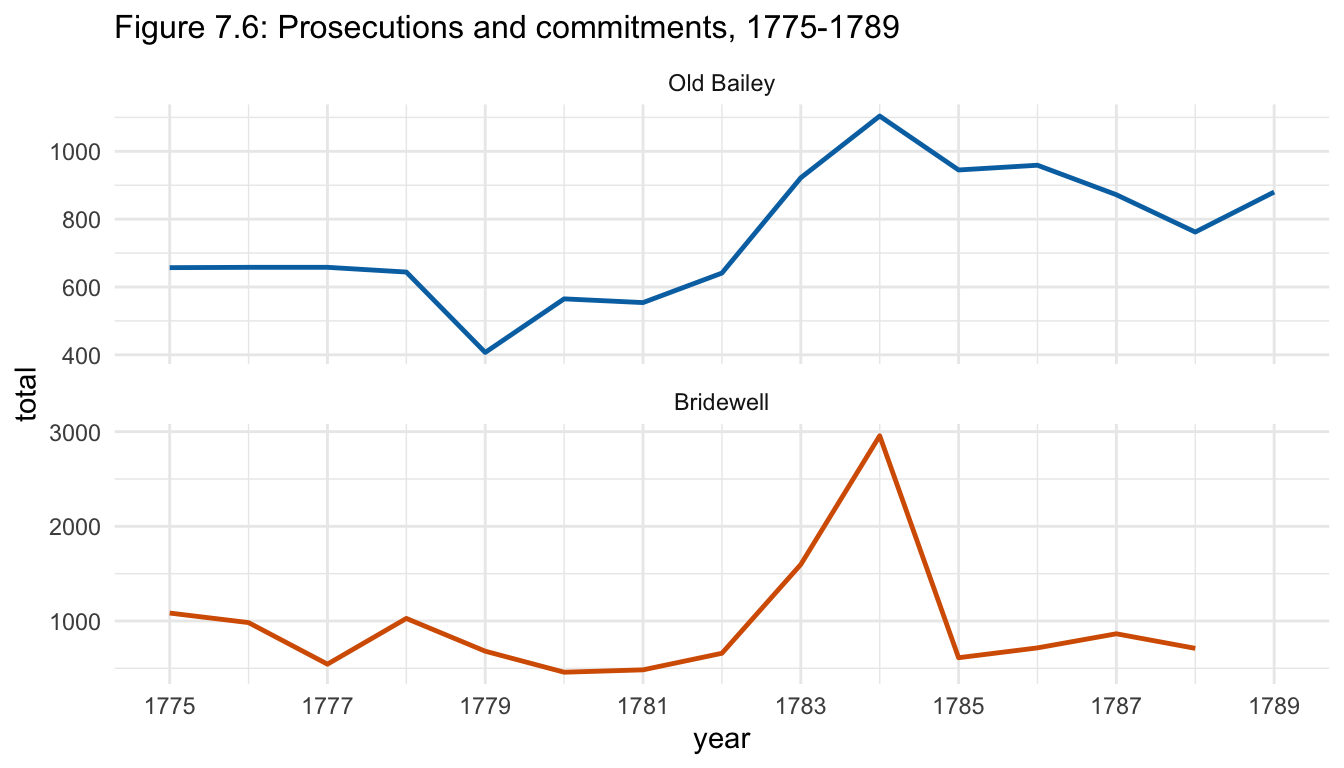

In part this can be seen in the business of the Old Bailey. In the years following the outbreak of hostilities in North America, the number of crimes tried remained level or declined, but following the mass prosecution of rioters in June and September 1780, the number of trials began to increase. This marked the beginning of a period of significant increase, peaking in 1784 following demobilisation. Unusually, the first phase of this increase, between 1779 and 1782 when the number of offences increased by more than half, occurred during wartime and affected men and women equally. A similar increase occurred at Bridewell, where commitments increased by 43.6 per cent between 1780 and

- Prosecutions increased more dramatically following the end of the war when, as normal, men accounted for a higher proportion of defendants.77 Between 1782 and 1784, the number of offences at the Old Bailey grew by 72.2 per cent, reaching a century-high total of 1,104 in 1784 when 80.8 per cent of the defendants were men. At Bridewell the growth in business was even more dramatic: the 385.6 per cent increase between 1782 and 1784 led to a century-high total of 2,956 commitments.

The first part of these increases did not occur during a period of economic hardship, and the most likely explanation is that in the tense period of insecurity following the riots, victims, neighbours and officers were more likely to prosecute suspected offenders formally, rather than rely on widely used traditional informal procedures. The activities of voluntary associations like the Honourable Artillery Company may also have contributed.78 It is also possible, though impossible to substantiate, that London’s alienated working poor became more willing (or felt more compelled) to break the law in these years.

In the early 1780s more Londoners than ever before found themselves in prison and before the courts. Around 1780 the house of correction in Clerkenwell received approximately 2,000 prisoners annually, and New Prison around 1,650.79 In the City, the compters received approximately 4,000 commitments a year.80 Even allowing for double counting and recidivism, if we include the Newgate and Bridewell the number of Londoners who were incarcerated in the years around 1783–4 exceeded 11,000 a year, or approximately 1.3 per cent of London’s total population.81 Since these figures do not include the Westminster or Surrey houses of correction and all those indicted at the City, Middlesex, Westminster and Surrey sessions (most of whom were bound over rather than imprisoned), the actual number brought before the authorities and accused of some form of criminal activity in these years must have amounted to around 3 per cent of the population. Not only does this figure betoken a significant increase in the desire of Londoners to prosecute deviance, it is also a measure of the unprecedented pressures the machinery of criminal justice faced in the early 1780s, at a time when the prisons were still overcrowded due to both the damage sustained in the Gordon Riots and the suspension of transportation.

Figure 7.6: Prosecutions and commitments, 1775-1789.

Source: Old Bailey Online, Statistics: Crime by year, 1775–1789 (counting by offence); Faramerz Dabhoiwala, ‘Summary justice in early modern London’, English Historical Review, 121:492 (2006), appendix (committals).

Online dataset: Crime Prosecutions (xlsx)

The consequences for London’s prisoners and prisons were profound. After years of policy chaos, the prison population was becoming both more experienced and more recalcitrant. A simple snapshot of the inmates of Newgate on 15 January 1783 – when the prison was still only partly repaired – reveals some of the prisoners’ characteristics. In addition to the traditional complement of prisoners awaiting trial (145), there were 211 ‘on orders’, primarily either sentenced directly to imprisonment or held from session to session awaiting transportation, all mixed together and free to argue and plan.82

The ‘Mother of Newgate’ was Lea Joseph Solomons, a widow and receiver, who had attempted to recoup her declining fortunes through arson and insurance fraud.83 In August 1779 she set fire to her rented house in hopes of claiming £400 in insurance on her working capital and clothes. At her trial she was convicted and sentenced to two years’ imprisonment at Newgate, and to pay a £100 fine. Following her release during the Gordon Riots and eventual recapture, she was simply left ‘to remain’ for years after. Among the men was Thomas Mooney, who had led a mob of between 300 and 400 people during the Gordon Riots and, although found not guilty of that offence, was later incarcerated in Bridewell for a minor offence, where he assaulted the keeper, earning himself a transfer to Newgate and years of uncertain imprisonment.84 There was also John Martin, described in the Proceedings as ‘a negro’, a sailor and probably a refugee from the American Revolution.85 He spent the whole of the summer and autumn of 1782 and the spring of 1783 in Newgate following his conviction for stealing a bundle of clothes. Sentenced to seven years’ transportation to the coast of Africa, he only escaped this fate by virtue of suffering from typhus. Essentially left to rot in prison, he was eventually sent to New South Wales on the First Fleet.86

These were desperate men and women, thrown together in desperate circumstances. Their experiences, and those of their numerous fellow inmates, contributed to the development of new attitudes, and new strategies of self-preservation.

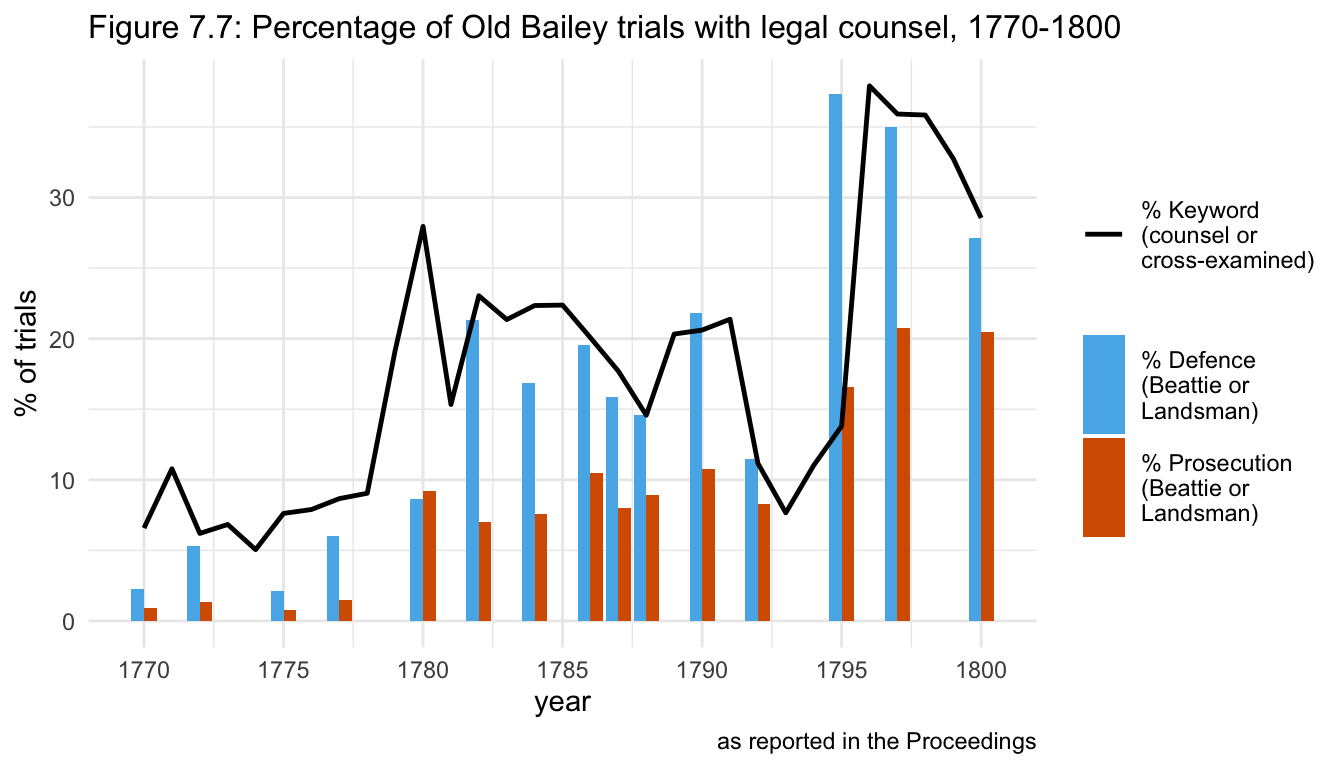

Lawyering up

The place, the theatre of justice, in which these new attitudes are most evident is the Old Bailey itself. These were the years when the ‘adversarial trial’ reached maturity with a dramatic increase in the number of defence counsel, which contributed to the development of new legal procedures and defendant rights.87 While we have seen that defence counsel were first allowed to appear at Old Bailey trials in 1732, and in the ensuing decades had frequently represented highwaymen, members of gangs and rioters, from the late 1770s there was a further step change in the number of defence counsel appearing. In part the evidence for this reflects the reporting in the Proceedings, since the presence of counsel was not routinely reported prior to the appointment of Edmund Hodgson as publisher in 1782.88 However, the sheer magnitude of the increase provides evidence that a change in the use and role of counsel took place in these years. According to Allyson May, these changes were ‘rooted in client behaviour rather than any theoretical imperatives on the part of the legal profession’.89 And as Figure 7.7 demonstrates, it was defendants rather than prosecutors who led the way. The growing number of defendants who appeared at the Old Bailey from the late 1770s came to realise that with the help of defence counsel they could challenge the courts and their prosecutors more effectively.

Figure 7.7: Percentage of Old Bailey trials with legal counsel, 1770-1800, as reported in the Proceedings.

Source: Old Bailey Online, keyword search for: counsel, council, councel, counc* etc.; and cross examined and cross examination; Beattie, ‘Scales of justice’, 227 (the figures for 1780 have been recalculated to include trials associated with the Gordon Riots); Landsman, ‘Rise of the contentious spirit’, 607.

NB: Figures for the early 1790s are incomplete, as trials resulting in an acquittal were eliminated from the published Proceedings between October 1790 and December 1792.

Online dataset: Legal Counsel at the Old Bailey 1715-1800 (xlsx)

The Gordon Riots, and the wave of prosecutions that followed, played a key role in advancing these changes. An examination of the sessions on either side of the riots makes it clear that it was precisely in these trials – held at the sessions beginning 28 June, just weeks after the riots – that counsel first appear in large numbers. In the May sessions prosecuting counsel is mentioned in one trial, and defence counsel in a further three. By contrast, in the June sessions thirty-three prosecuting counsel are explicitly mentioned (reflecting the state’s desire to convict the rioters) and twenty-one for the defence.90 Never before had counsel appeared at so many trials in a single Old Bailey sessions.

To some extent this particular meeting of the court is anomalous – in subsequent sessions the number of defence counsel gradually but briefly declined to a level not much higher than in the years prior to the riots – but a new and clear pattern quickly emerged that saw the proportion of trials with counsel reach unprecedented levels for the remainder of the decade. As well as acting as a catalyst for new attitudes to prosecution and imprisonment on the part of victims and the authorities, the riots and their aftermath also represent a significant escalation in the role of defence lawyers in the courtroom. It is the Gordon Riots that mark the moment when defendants en masse at the Old Bailey decided it was time to get lawyered up against a system they perceived as rigged against them. And if convicted and sentenced to death, some members of this same cohort of men and women decided, by refusing the royal pardon, that it was worth the risk of death to challenge the judges.

While these changes were well in train before William Garrow came to the bar in November 1783, Garrow’s presence was nonetheless transformative. The most prominent defence lawyer of the eighteenth century, from his first trial at the Old Bailey he proved himself a master of cross-examination and judicial attack. In the next ten years Garrow is estimated to have acted in over a thousand cases, about three-quarters for the defence. It has been argued that he laid the foundation for the notion that the defendant was innocent until proven guilty, and that the guilt or innocence of the defendant should be proven through an adversarial procedure.91 But what historians have yet to explore is the nature of the group of men and women who were paying Garrow to act in this capacity.

As already noted, in the decade after the creation of the first hulks there was a generation of men and women who found themselves held for long periods in unreformed prisons organised in such a way as to allow both social interaction among prisoners and (with the exception of the hulks) the incorporation of a wider group of visitors into prison culture. These men and women lived together for years on end, many under the shadow of the gallows. And it is their shared knowledge of criminal justice and its officers that led to a growing sophistication in the courtroom and a viral enthusiasm to deploy Garrow and other counsel in their defence.

A simple measure of the origins of this change in attitudes can be found in the characteristics shared by Garrow’s first fifty defence clients. All but seven individuals (86 per cent) had been previously tried at the Old Bailey, and hence held for a time in New Prison or Newgate, on at least one occasion prior to the trial in which Garrow was involved. Typical of Garrow’s clients was Richard alias Jonas Wooldridge, who, without benefit of counsel, and with three others, had been found guilty of counterfeiting in September 1781.92 He was fined one shilling and sentenced to twelve months imprisonment in Newgate, which he served in New Prison while Newgate was out of commission.93 Three years later, when he was again tried for the same offence, Wooldridge employed Garrow as his counsel, and as Wooldridge looked on, Garrow attacked the prosecutor for being motivated by a desire to secure her husband’s acquittal on a similar charge, raised a technical point of law and argued with the judges. In the end, Garrow left the court consumed by laughter at the prosecutor’s expense, with Wooldridge a free man.94 The benefits of obtaining a lawyer, and a desire to employ Garrow, were part of the expertise that circulated through New Prison and Newgate in these years.

The significance of this change in defendant behaviour is reinforced by an appreciation of the costs involved. Between prison garnish, living expenses and gaol fees, being accused of any crime in the eighteenth century was an expensive proposition that required the support of friends. Hiring defence counsel, which could easily cost £1 or more per trial, substantially increased the cost.95 And yet, lower-class Londoners managed to raise this money: among Garrow’s first fifty clients were seven servants (plus a servant’s wife), four labourers, a laundress, a broker and dealer in old iron and rags, a buyer and seller of old clothes, a chandler, a porter and several craftsmen (cooper, gardener, hair dresser, ivory turner, shoemaker, silk throwster, stone mason).96 We do not know how prisoners managed to secure this money, but with their lives at stake (as the number of hangings increased) desperation became the mother of invention. Funds are likely to have come from some combination of charity (including from fellow prisoners), possible reduced charges from lawyers keen to make a name for themselves in the courtroom, the proceeds of crime, and family and friends. Patrick Madan, for example, received financial support from his sister. In his letters home, among the details of his attempts to escape from Newgate, the problems he was encountering in smuggling gaol-breaking equipment in a pie and the idle gossip of the prison community, he reported how, with his sister’s assistance, he had, ‘procured [a] lawyer’, an ‘Old Bailey Solicitor’.97 The fact that several hundred were able to pay counsel in the 1780s, many of whom were in lower-class occupations and including for the first time many who were accused of non-capital offences, is testimony to both the desperation and the combativeness of Old Bailey defendants in these years.98

Garrow’s most successful defence strategy is also revealing of the attitudes of prisoners in the aftermath of the riots. His most common rhetorical device was to question the financial interests of the prosecution, and, despite John Fielding ‘s attempts to make the Bow Street Runners respectable, to paint the varied officers of the law in the lurid and corrupt colours of a thief-taker. Garrow aggressively raised this long-standing defence tactic to a new level. Again and again he asked what the prosecution hoped to get out of a conviction. In the process, and on behalf of hundreds of prisoners, he held to account a system that was perceived as out of control, and he questioned the very basis of the evolving system of police. For the most part, he avoided using this tactic when cross-examining senior Runners from Bow Street, who with vast courtroom experience, quickly developed the ready defence of asking Garrow what he himself earned.99 But Garrow was confident enough of the jury’s dislike of the other Runners to characterise them in open court as the ’myrmidons’, or hired ruffians ’that attend at the Brown-bear’.100 In making this kind of case, Garrow cut with the grain of public opinion about the new system of police, an opinion that encompassed both his clients and at least some members of the jury.

There is some evidence that those who were defended by counsel were more likely to be found not guilty: over half of Garrow’s clients were acquitted, compared to just 35 per cent of all defendants in the same years.101 And the ability of some offenders such as Charlotte Walker to avoid conviction for long periods with the assistance of counsel is indeed impressive.102 However, with prosecution counsel also increasingly present, the balance of power in the courtroom had not dramatically changed. Overall, the new frequency with which defence counsel were employed was as likely to have been motivated by fear as by hubris. Many of Garrow’s clients would likely have agreed with Benjamin Brown, who despaired when his counsel failed to appear: ‘I thought I was prepared with a counsel, but am entirely lost’.103

According to John Langbein one of the consequences of the growing use of barristers for the defence was the silencing of the defendant, as lawyers shifted the focus of the trial to whether the prosecution had proved its case, and defendants let their counsel make their case for them.104 But perhaps encouraged by the development of a more adversarial tone in criminal trials, those defendants who did speak began to do so in an increasingly confident tone, justifying their crimes with claims that they had been driven to steal by ‘starvation’, ‘necessity’ and ‘distress’. Despite the dangers associated with admitting culpability (such testimony only increased the chance of conviction, and punishments tended to be no lighter), defendants challenged the court to convict them in the face of increasingly eloquent pleas for mercy. Thomas Archer, accused in 1784 of stealing two loaves of bread worth 15 pence from the basket of a journeyman baker making deliveries, told the court:

Nonetheless, he was convicted, sentenced to be publicly whipped and passed back to his parish. Mary Smith received a little more mercy. Charged in 1783 with stealing two linen shirts from ‘a poor woman’ in the house in which she lodged, she told the court:

Although she was also convicted, the jury recommended her to mercy, and the court ordered her to be privately whipped and discharged, telling her, ‘You will have favour shewn to you this time; but if you are not able to maintain yourself by honest industry, apply to your parish’.105 While this growing practice of defendants justifying their crimes may often have been ineffective or even counterproductive, their growing willingness to stand up to the court and make such pleas, even without the aid of a lawyer, is indicative of a new assertiveness among prisoners.

The impact of legal counsel was even wider. Those who acted at the Old Bailey, or the solicitors they worked with, also practised in other London courts, defending the accused, prosecuting counter-accusations and challenging poor law orders. Lawyers had been involved in hearings at Bow Street since at least 1772, when John Fielding had begun conducting regular ‘re-examinations’.106 One such attorney, Thomas Ayrton, ‘an attorney at King’s Bench’, brought a suit which successfully challenged Fielding’s practices. Following an illness which lasted a few months, Fielding died in November 1780, but the hearings continued under a justice with less clout, William Addington. Ayrton brought his suit in December following an altercation at a hearing conducted at Bow Street by Addington of a suspected highway robber, in which Ayrton, as usual, was not permitted to cross-examine the prosecutor. The resulting legal challenge, tried in front of Lord Mansfield, ended with a strong censure of the Bow Street practice of pre-trial hearings, particularly the extensive pre-trial publicity they received. As a consequence of this case, newspapers stopped reporting the hearings, and defendants were no longer expected to disclose their evidence in advance of the trial. It is likely that the growing practice of solicitors representing accused felons at such pre-trial hearings resulted in further challenges to the procedures in the ensuing decades.107 Solicitors also increasingly aided the poor in cases of poor law appeals, vagrancy and debt. John Silvester, one of the most active Old Bailey counsel, regularly appeared on briefs for settlement and vagrancy cases in the 1770s, although we know little about the nature of his practice.108 Just as counsel hired by defendants forced legal innovations which worked to their advantage in the courts, solicitors may have stimulated changes in poor law practice which benefited the poor.

Punishment transformed

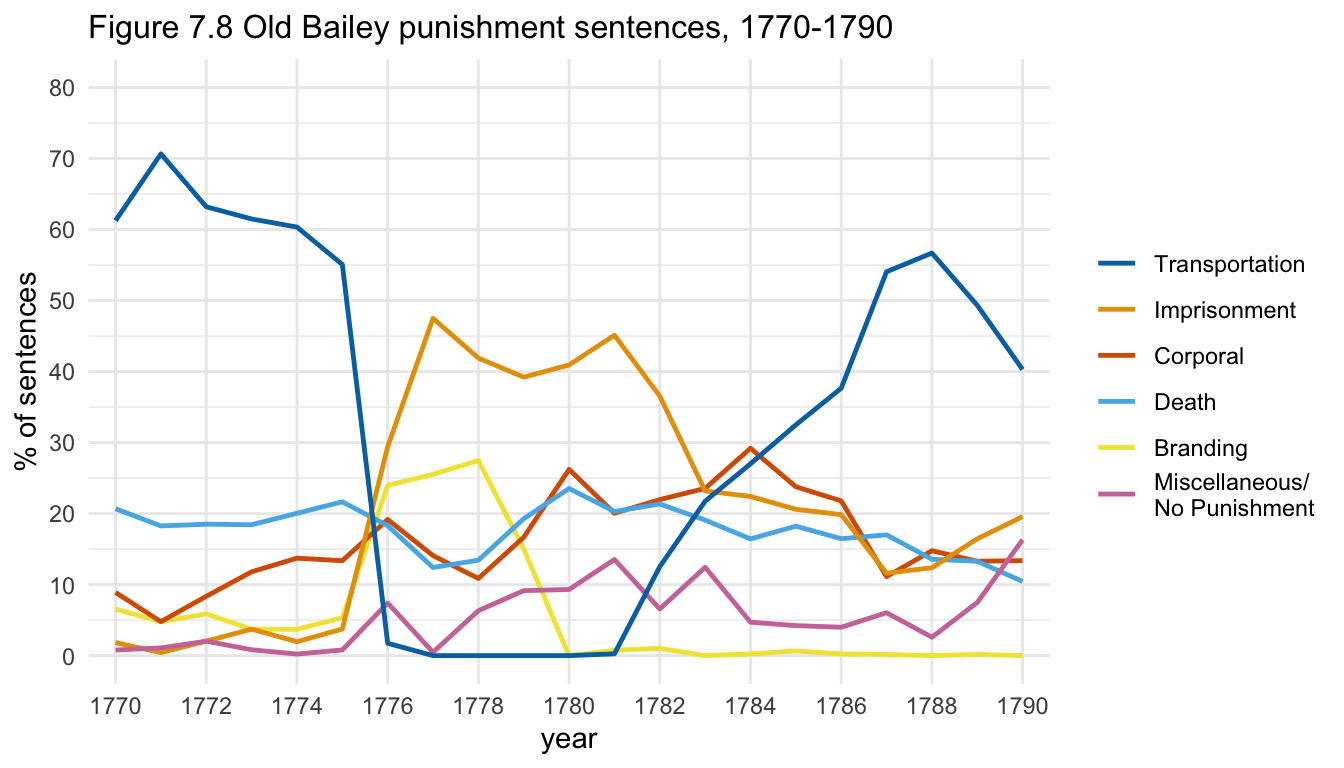

During these same years punishment was further transformed, driven by both social anxiety and the behaviour of convicts. Following the Gordon Riots, more defendants were convicted and punishments became harsher. Between 1770–81 and 1782–6, the conviction rate at the Old Bailey (both full and partial verdicts) increased, despite the increased presence of defence counsel, from 55 to 61 per cent.109 With transportation unavailable until 1787 (although sentencing resumed in 1781), there were substantial increases in the number and proportion of convicts who were whipped, imprisoned and sentenced to death.

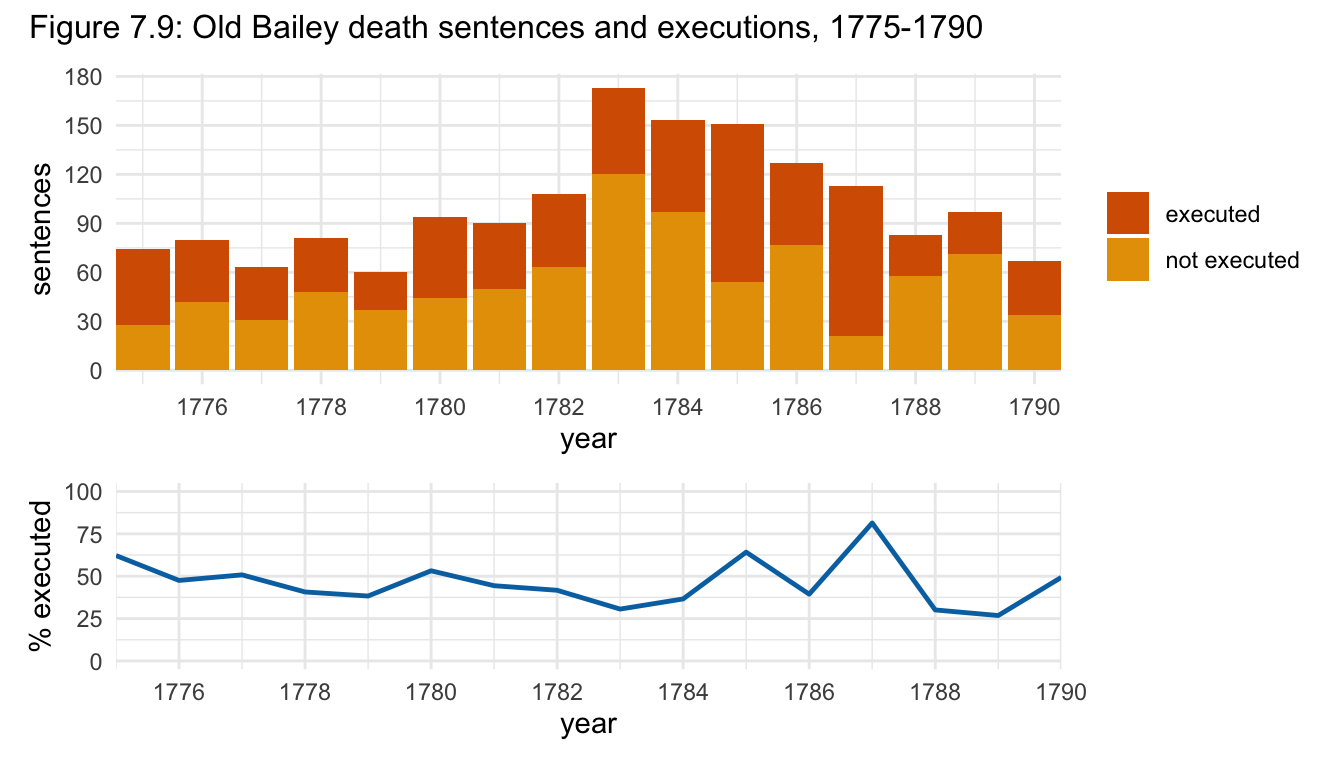

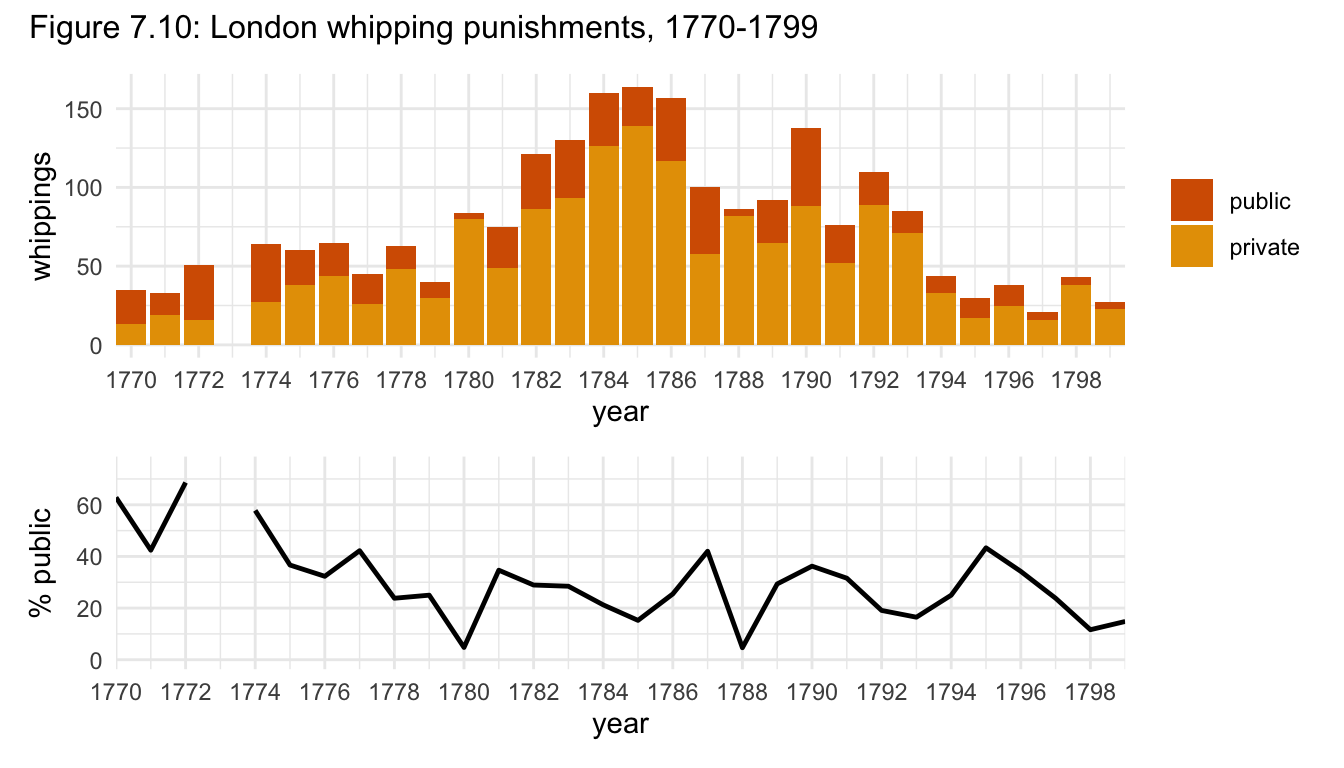

Following the suspension of transportation, the authorities initially relied on traditional punishments. The number of sentences of branding per year increased from an average of 17.7 between 1750 and 1775 to 100.5 between 1776 and 1779, when it was abolished as a punishment for crimes subject to benefit of clergy.110 Similarly, following a decline in the use of whippings in the 1750s, the punishment was substantially revived in the late 1770s. As recorded by the Sheriff of London, the number of whippings carried out (including those sentenced at quarter sessions) increased from 40 offenders in 1779 to 164 in 1785, the largest annual total in the century. Similarly, whereas 60 felons were sentenced to death in 1779, this figure almost tripled to 173 in 1783. Executions increased even more dramatically. Whereas 23 were executed in 1779, there were 97 executions in 1785, the bloodiest year in the century. Not only were more convicts hanged, but they formed a growing percentage of all those sentenced to death, reaching 64.2 per cent of the condemned in 1785 and 81.4 per cent in 1787. This was a direct result of a decision by the Home Secretary in September 1782 to refuse to grant pardons (as had often occurred previously) to those convicted of robberies and burglaries ‘attended with acts of great cruelty’.111 All told, 500 people were hanged in London in the seven years following 1780, almost a third of all those hanged in the eighteenth century.

Figure 7.8 Old Bailey punishment sentences, 1770-1790.

Source: Old Bailey Online: Statistics: Punishments by year, 1770–1790, counting by defendant.

Online dataset: Punishment Statistics 1690-1800 (xlsx)

Figure 7.9: Old Bailey death sentences and executions, 1775-1790.

Source: PP, House of Commons Sessional Papers, 1818, xvi, 185–7 and 1819, xvii, 295–9.

Online dataset: Death Sentences and Executions 1749-1806 (xlsx)

The increasing severity of punishment in response to the twin crises of the Gordon Riots and the post-war crime wave was accompanied by changes in implementation. Both whippings and executions were carried out in new ways which served to reduce the role of the watching crowd and ensure that the authorities retained control of the ritual, addressing concerns raised by Henry Fielding in 1751. Accelerating a long-term trend which had begun in the 1730s, whippings were primarily conducted in private. Rather than being carried out along a street for a hundred yards ‘at the cart’s tail’, whippings were increasingly staged at a stationary whipping post or inside prisons. The proportion of whippings carried out in public (whether sentenced at the Old Bailey or quarter sessions) declined by almost half, from 42.8 per cent in the 1770s to just 23.1 per cent in the 1780s.112 As noted previously, the motivations for this shift in penal strategy are unclear. While there is no direct evidence that the authorities were concerned about potential disorder among the crowds which witnessed whippings, this is suggested by the fact that from 1785 the City of London began to use large numbers of ‘extra constables’ to police public punishments.113

Figure 7.10: London whipping punishments, 1770-1799.

Source: TNA, Sheriff’s Cravings, T64/262, T90/165-168.

Online dataset: London Whipping Punishments 1770-1799 (xlsx)

Similar concerns lay behind the decision in the autumn of 1783 to move public executions from their traditional location at Tyburn on the western edge of the metropolis to immediately outside Newgate prison (whose reconstruction following the Gordon Riots was nearly complete). As a result, the sometimes disorderly procession carrying the condemned in a cart from Newgate to Tyburn was abandoned, executions were held earlier in the day and the size of the crowds which were able to watch executions was reduced. Furthermore, the introduction of the ‘drop’ speeded up hangings, making it difficult for the condemned to make a show of dying ‘game’ and giving the crowd less of an opportunity to sympathise with their suffering. Executions would now take place in front of the rebuilt Newgate’s sober facade, with the condemned brought out onto the scaffold only shortly before their actual executions.

The motivations for this significant change in the execution ritual have been variously ascribed by historians to a desire to protect property values in the west end, concerns to enhance the impact of prospective executions on the convicts’ imaginations and, in the latest article on the subject, attempts to improve the deterrent effect on the attending crowd.114 As Simon Devereaux argues, ‘the most compelling impetus for the abolition of Tyburn was a penal crisis of unprecedented proportions’, with the existing regime manifestly failing to stop the apparently relentless increase in crime. Immediately before the decision to transfer executions to Newgate was taken, twenty-six men who had mutinied on a transport ship they believed was destined for Africa had been convicted, and six were hanged.115 In this context the decision to stage executions at Newgate was made in an attempt, much like the multiple locations of the executions of the Gordon rioters, to re-establish control over an increasingly intransigent criminal population. But the authorities also sought to stop the crowd disorder which still sometimes accompanied processions to Tyburn and subsequent executions. As the sheriffs Thomas Skinner and Barnard Turner (who had been involved in suppressing the Gordon Riots) argued in their pamphlet justifying the change:

The Croud of Spectators will probably be more orderly, because less numerous; and more subject to controul by being more confined; and also because it will be free from the accession of stragglers whom a Tyburn procession usually gathers in its passage, and who make the most wanton part of it.116

The problem of crowd disorder nonetheless persisted, contributing to the scaling back of the number of prisoners executed in London after the peaks in 1785 and 1787. In 1788 this figure dropped from 92 to 25, and the number stayed low for the rest of the century: between 1789 and 1800 executions averaged 22 per year. This is because the bloodbath in the mid-1780s placed capital punishment ‘under attack to a degree never before experienced’.117 Opposition to large-scale executions can already be seen in 1780, when Edmund Burke unsuccessfully lobbied for the number of Gordon rioters to be executed to be limited to six, since, he wrote: ‘a very great part of the lower, and some of the middling people of this city, are in a very critical disposition … [and] may very easily be exasperated, by an injudicious severity, into desperate resolutions’.118 In 1784 the housekeeper at the Old Bailey was worried that ‘evil minded people would gain access to the yard where the scaffold was kept between executions and set fire to it’.119 Changing the location of executions had not allayed concerns about the behaviour of both the crowd and the condemned: a correspondent to the Gentleman’s Magazine in 1784 complained that ‘Our executions seem to have lost all their good effects … the only solicitude too many of [the crowd] discover is, whether the criminals die hard’.120 That concern about the impact of frequent executions was shared at the highest levels of government is indicated by the worry expressed by the prime minister, William Pitt, in 1789 that they would create the wrong ‘public impression’.121

If both public attitudes and crowd behaviour rendered large-scale executions no longer feasible, it was necessary to increase the use of secondary punishments. Whipping was deemed adequate only for minor offences, leaving imprisonment and transportation (if a new destination could be found) as the only alternatives. But owing to the trail of destruction left by the Gordon rioters, London’s prisons in the early 1780s were in a state of chaos. Newgate had suffered most and was only gradually brought back into use, one section at a time. It would not be fully repaired until the summer of 1784. Most London prisoners were therefore crowded into the hastily repaired New Prison and Middlesex house of correction in Clerkenwell, where convicts serving sentences of imprisonment joined those arrested and waiting to stand trial, petty offenders committed by summary jurisdiction to short terms of hard labour, and debtors. Since it was necessary to house convicts who previously would have been transported as well as those displaced from Newgate, the crowding was intense. The resulting poor conditions and inevitable intermingling among different classes of prisoners contributed to the further evolution of a culture of resistance among London’s prison populations. Managing both prisons became the main item of business discussed by the Middlesex justices at their meetings throughout the early 1780s.

The scale of the problem can be seen in the fact that between May and September 1780 a total of 678 prisoners were committed to New Prison.122 The number committed to the house of correction is not known, but by October the Middlesex justices expressed concern that ‘a far greater number of persons is now in general imprisoned there than what the building is capable of containing with safety and convenience’. In 1781–2, the number of prisoners held at any one time ranged from 134 to 233; there were 130 more in New Prison. We have seen that prison crowding was a serious issue in the years between the suspension of transportation and the Gordon Riots; the difference now was that London’s strongest prison was temporarily unusable, and prisoners were forced into buildings not designed to hold large numbers of felons. To prevent escapes, a military guard was placed at both prisons.123 When Newgate fully reopened in 1784 the poor conditions and overcrowding were simply transferred. In November, the keeper reported that the prison contained 362 felons and 167 debtors, and about 300 of the 529 prisoners lacked rugs to sleep on and keep themselves warm.124 A year later the prison held 680 prisoners, and in October 1788 almost 750.125

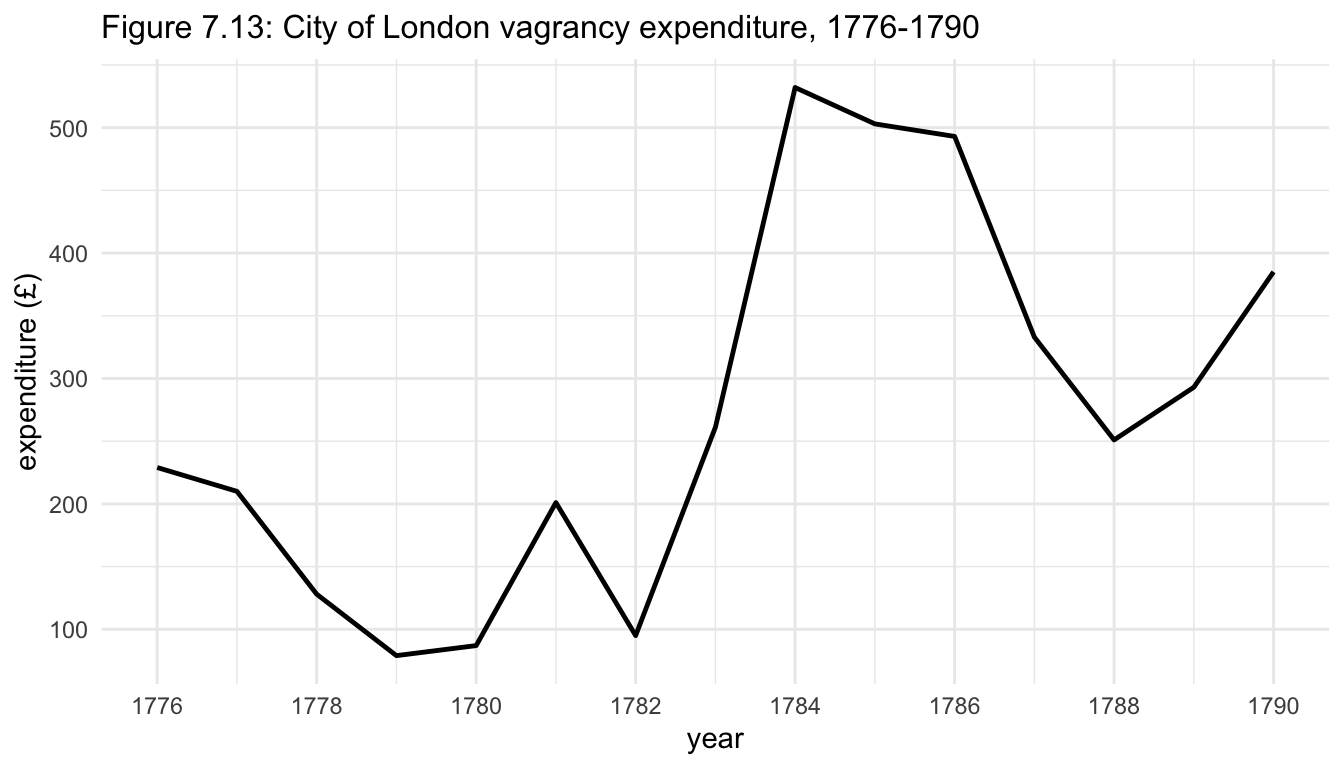

The presence of so many long-term prisoners (convicts serving sentences of imprisonment, and those awaiting transportation) continued to be problematic. Reports from 1781 indicate that the Clerkenwell house of correction held between 55 and 65 convicted felons, while a list of the prisoners in February 1783 included 77 prisoners who had been convicted at the Old Bailey, and a further 18 convicted at the Middlesex sessions.126 Some had been there since April 1781. The previous month the keeper of New Prison voiced concern about ‘the capital convicts now in his custody who are very numerous and licentious and continually endeavouring to escape’, and a week later a committee of justices reported that convicts who ‘continue there months and for years [are] in an idle and worse than an useless state corrupting each other and forming confederacies dangerous to the public … [they are] ever making disturbances and riots within the goale and encouraging others to misbehave’.127 Similar concerns were apparently present at the City of London Bridewell, where the number of commitments increased dramatically between 1781 and 1784. In December 1782 the General Prison Committee issued new regulations restricting visitors, ordered that cutlasses be kept in a case in the watch house and stipulated that ‘a Rattle be Provided … in Case of any Disturbance [an officer] may Alarm the Beadle at the Lodge that the Gate of the Hospital may be immediately Locked to Prevent Escapes’.128

Despite these precautions, including the presence of military guards, the rebellious mood among the prisoners led to a rash of escapes and mutinies. We have already seen that there was no shortage of escapes in the five years leading up to the Gordon Riots. But in the chaotic years which followed, leading to the decision to establish a penal colony in Australia, escapes multiplied, and London’s prisons and transport ships became a seething cauldron of discontent (Figure 7.2).

In the prisons alone, the seven multiple escapes and three attempts between July 1780 and June 1785 demonstrate both the desperation and the new-found confidence of convict prisoners, particularly at the recently rebuilt New Prison. In December 1780, three convicted felons, William Mackenzie, Joseph Caddy and George Bartington, escaped. Their recapture cost £60 and earned the keeper a harsh rebuke from the Middlesex justices.129 Four months later, on 29 April 1781, a further escape attempt from the same prison was mounted by the inmates, who

in an unlawful, riotous and tumultuous manner assembled themselves together and attempted to break out of and escape … and with force and arms assaulted [the guards] stationed to keep the said prison.130

The guards were issued with guns and in the mêlée that followed William Bell, a thief a few months into a year-long sentence of hard labour, was shot and killed.131 Five months later still, on 3 September 1781, once again the prisoners ’assembled themselves together and attempted to break out of and escape from the … prison’.132 Again, guns were issued, and this time, three prisoners were shot and killed: Benjamin Lees, William Trenter and George Hutton.

Later the same month, and in direct response to this incident, the keeper, Samuel Newport, petitioned the Middlesex justices, who incorporated his observations in a further petition of their own to the judges at the Old Bailey, describing the mood of the prisoners.

Newport concluded his plea with the observation that the prisoners were possessed of a ‘determined Resolution… [for a] General Escape’.133 In response, a troop of soldiers was stationed in the gaol for two years, at a cost of £16 per quarter, in an attempt to calm what the local commander would later describe as the’riotous and dangerous state of the prisons’.134 And as a carrot to counterbalance this stick of military authority, the daily allowance of food provided to each prisoner was doubled, and for the first time shoes and clothes were made available for poor prisoners.135

Samuel Newport’s fears were nonetheless realised. In February 1782 he informed the justices ‘that several prisoners had attempted a break out of one of the wards and had destroyed some part thereof’.136 Seven months later, ‘two prisoners … made their escape’ from Newgate.137 And in November of the same year, William Wood, a prisoner at the house of correction at Clerkenwell, directly next door to New Prison, put a pistol to the head of Thomas Mumford and threatened to blow his head off if he did not deliver the keys; while John Fitzgerald, his legs still in irons, threatened to cut John Brown ‘s throat if he did not cooperate. In total, thirty-one people, all classified as ’vagrants’, escaped that night.138

A clear measure of the fear and anxiety created in the minds of the administrators of criminal justice by this new spirit of rebellion and escape can be found in the reactions of the keeper of New Prison to a riot, perhaps an attempted escape, perhaps just a scuffle, that occurred on 1 August 1784. Some stones were thrown and a complaint was made by the women prisoners because their victuals were not delivered as normal at the open gate to their yard, but through a serving hatch. A broomstick was pushed through the gate in a threatening manner, and someone yelled that they would burn the prison. In a desperate response to what most witnesses described as a relatively minor affray, the keeper broke open the arms cabinet and distributed weapons to both his own staff and a couple of soldiers who happened to be visiting. In the confusion that followed Sarah Scott, seven months pregnant and mother of two, was shot in the face and killed. No escape was effected, but the fear of one, and the pride of prisoners in being able to create that fear, was fully reflected in the trial for murder that followed, when the prisoners’ testimony reveals a remarkable self-confidence. When called to testify against William Stevenson, the man who fired the fatal shot, each prisoner seemed more keen than the last to claim a reputation as an escape artist and rabble- rouser. Daniel Hopkins claimed he was only in New Prison in consequence of ‘breaking out of that [same] gaol’, while Thomas Jones claimed to have escaped from Newgate. The counsel for the defence suggested that Jones ‘was so bad a fellow, that the keeper got some of his own people to bail [him], that [he] might not corrupt the whole gaol’. To this Jones heartily concurred,’Right, Sir! Very right, Sir! Very right, Sir! ’.139

A similar narrative was played out on the hulks. Owing to prison overcrowding and the renewal of court sentences of transportation (despite the fact no destination had been identified), convicts continued to be kept there. Their continuing use from 1782, despite their known limitations, was justified as a stop-gap measure until transportation could resume. In December the removal of additional prisoners to the hulks was justified in a Treasury minute by the fact ‘that the Gaol of Newgate is crowded with prisoners to a very inconvenient degree’.

However, conditions on the hulks were at least as bad as in the prisons, and once again some of the convicts escaped. And once again, those re-arrested justified their actions by the harsh treatment they had received. Charles Peyton told the court in 1785 ‘I have only to say, I had very hard usage on board the hulk’.140 George Morley, tried for escaping for a second time, said ‘I cannot disown the charge of being guilty, the reason of my making my escape, was the ill treatment I received after my first escape’. Morley elaborated:

I was run over across my loins, I am lame, I was always struck without a cause, when I tried to do the utmost of my endeavour, and I hope the merciful Jury will take it into consideration, and send me to any other place: the allowance [of food and drink] is but two pints of barley water, from three in the morning, till six in the afternoon, and there is half a brown loaf, and half an ox cheek for six hearty young men, and the ballast that I heaved up, weighs a ton weight, and is fit for a horse to do, and I am entirely a cripple now, and an object [of mercy].141

Memories of such harsh treatment were not easily erased. Charles Peat spent some time on one of the hulks before being taken on the transport ship the Mercury in 1784, from which he escaped following a prisoners’ mutiny. At his trial for returning from transportation he told the court ‘Whilst I was on board the hulk, I had the mortification of seeing my fellow sufferers die daily, to the amount of two hundred and fifty’.142 Joseph Morrell had extensive experience of the hulks between 1784 and 1789.143 Convicted of grand larceny in 1784 and sentenced to transportation, he was committed to the hulk the Censor , moved to the Justicia and then to a hospital ship, from which he escaped in 1786. Indicted for returning from transportation, he told the court ‘I suffered such hardships, that I made my escape’. Convicted and sentenced to death but with a recommendation for mercy from the jury, Morrell was apparently sent to Newgate. Before he was sentenced, he pleaded ‘I hope I shall not go on board any more hulks; I accept my sentence very freely, only not to send me on board the hulks’.144

Throughout the century there was a persistent pattern of prison escapes, and prisoner collusion in devising defence strategies for their trials. But the 1780s witnessed a significant escalation of oppositional behaviour among London prisoners, defendants and convicts, both at the Old Bailey and in the prisons. More than a simple, and perhaps understandable rejection of the carceral chaos that characterised London in these years, the mutinies and mass escapes, and confident behaviour in court, constituted a newly self-confident plebeian challenge to the institutions of criminal justice. The authorities were forced to respond.

Transportation in name only