Introduction

On Saturday 18 November 1750, Westminster Bridge was opened to the public for the first time. By linking Westminster to Southwark, it changed the character of the metropolis and laid the foundation for rapid expansion south of the river. Built of Portland stone in a plain neoclassical style, it was ‘allowed by Judges of Architecture to be one of the grandest Bridges in the World’. That night a procession crossed the new bridge with ‘Trumpets, Kettle-Drums, &c. with Guns firing during the Ceremony’. And on Sunday, ‘Westminster was all Day like a Fair, with People going to view the Bridge and walk over it’. With twelve new salaried watchmen and thirty-two street lights, the bridge set the tone and style for a fifty-year period of civic building in the capital that would include many of the city’s prisons and lock-ups, court houses and workhouses. And while ‘The Pickpockets made a fine Market of it, and many People lost their Money and Watches’, the bridge symbolised a new and more orderly London. But it also reinforced the sometimes brutal character of the systems of justice and social care that governed the lives of London’s working people. It became one of the specific and peculiar places where small crimes were made capital under statute law. Westminster Bridge joined the ‘bloody code’: ‘Persons wilfully and maliciously destroying or damaging the said Bridge … shall suffer Death as Felons without Benefit of Clergy.’ New and old architecture, new and old systems of police and punishment, new and old conceptions of community and social obligation jostled cheek by jowl in the 1750s, pitting innovation against social cohesion and resulting in growing conflict.

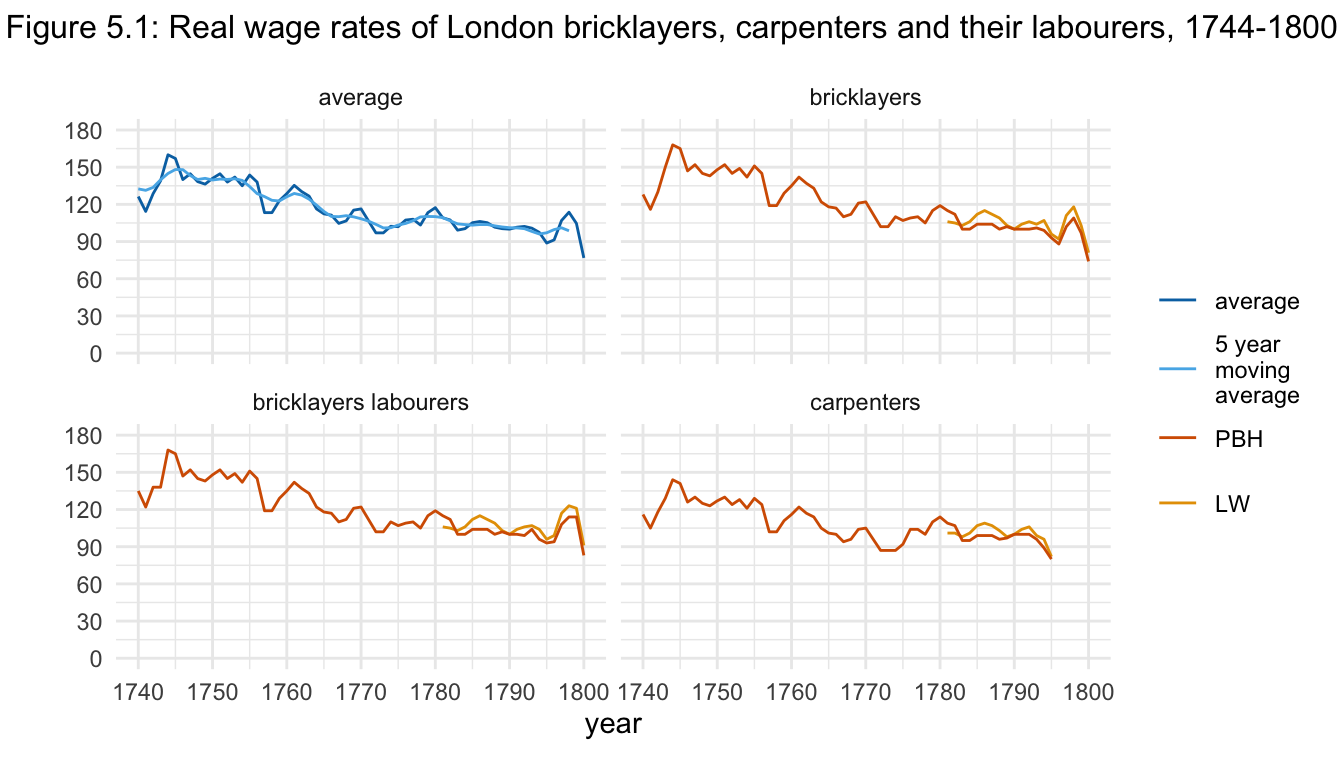

London at mid-century was wet and miserable. A long series of damp winters and soaking summers led to mildewed crops and rising food prices. After twenty relatively good years of high real wages and low food prices, the economic well-being of London’s workers was challenged year on year. In 1756 the highest wheat prices for two generations and a significant drop in real wages were witnessed, the beginning of a half-century-long decline that would reach its nadir only in the 1790s. This decline in living standards exacerbated on-going conflicts between plebeian Londoners and the ambitions of those who were responsible for the building of Westminster Bridge.

In the years following the end of the War of the Austrian Succession in 1748, the country’s governors felt under siege. Not only were there concerns about a major crime wave in London, but there were violent confrontations with gangs of smugglers on the south coast, turnpike riots in the West Country and keelmen’s strikes on the Tyne. It is against this backdrop of economic hardship and elite insecurity that the developments at mid-century must be read. While the comfortable middling sort were worrying about crime, and parliament was passing the Murder Act in 1752, mandating the immediate execution and dissection of those convicted of murder, artisans and labourers were beginning to struggle to make ends meet. And when Henry and John Fielding were designing a comprehensively reorganised system of poor relief and criminal justice, breathing new life into the discredited system of thief-takers and rewards, some of the working poor were going hungry. The gangs and criminals of the capital came into ever more open conflict with the authorities, while riots at Tyburn and popular disgust at the treatment of Bosavern Penlez cast a harsh light on the policies of the state and justices of the peace. Conflict on the streets and in the courtroom helped to define the growing gulf between self-styled reformers and their many enemies. Projectors and philanthropists used the new-fangled power of the associational charities to create the appearance of a more ordered metropolis where crime was not tolerated, and the poor were virtuous and hard working. However, through the Foundling Hospital they, in fact, inadvertently committed mass murder by neglect. In this difficult decade, plebeian London learned harsh lessons and in response refined their oppositional tactics and developed new ones, with varying degrees of success.

The crime wave and poverty’s knock

In July 1748, as the hostilities of the War of the Austrian Succession waned and the peace negotiations leading to the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle accelerated (it was signed in October), London’s elites grew anxious about rising crime and poverty. Many anticipated a post-war crime wave, in what turned out to be a self-fulfilling prophecy. From late 1747, long before the troops arrived home and during a period of low food prices and temporarily rising real wages, crime reporting in the press increased, and victims of crime and judicial officials began to press charges more regularly. The same period witnessed renewed attempts by the City of London to control begging and vagrancy. At the beginning of February 1748–9, the Common Council determined to publicise the awards available for apprehending vagrants and admonished constables and private citizens to do their duty and prosecute the ‘great numbers of beggars rogues and vagabonds’ that pestered ‘the streets & publick passages of this city’. In the autumn of 1749, the grand jury in the City followed with a presentment that repeated the old claim that ‘idle vagrants & common beggars’ were a particular danger ’to child-bearing women’.

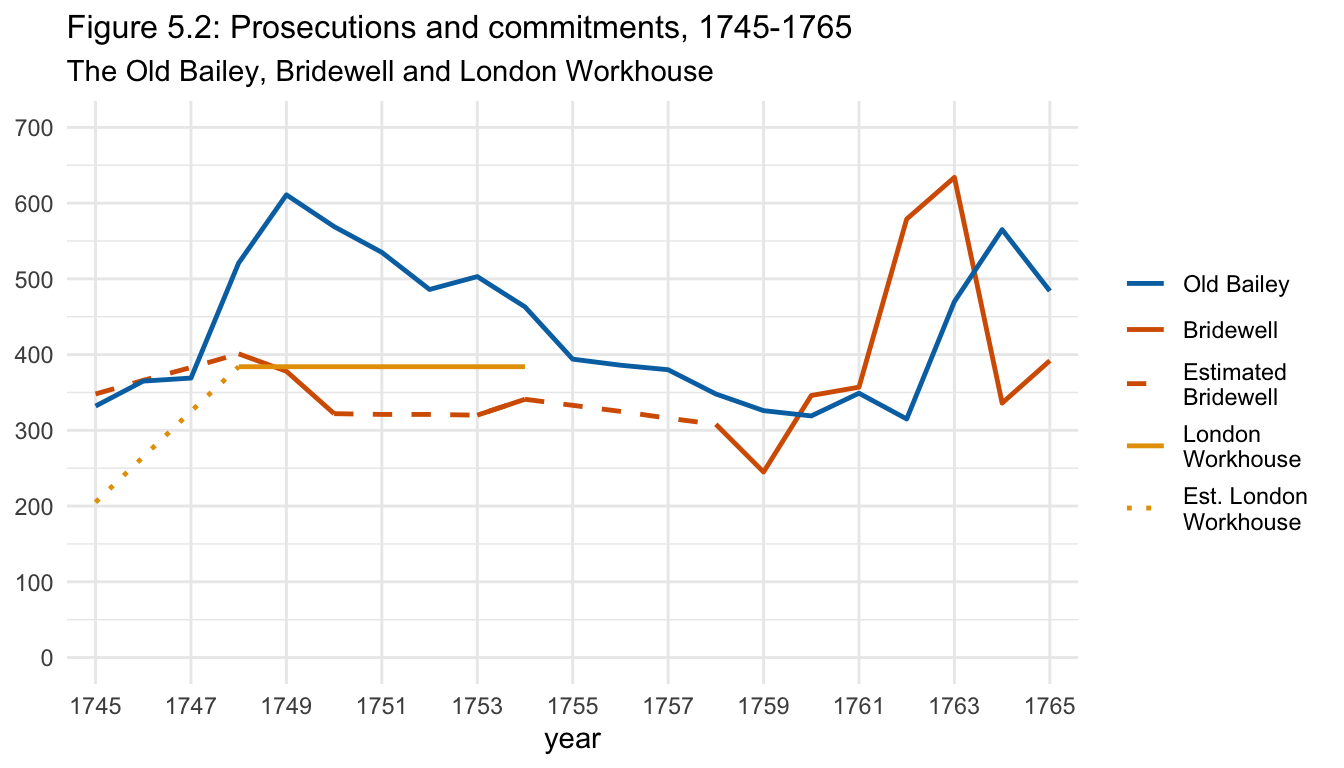

These concerns contributed to a wave of prosecutions at the end of the 1740s. The total number of offences tried at the Old Bailey increased by 84 per cent between 1745 and 1749, and while equivalent data from Bridewell and the London Workhouse are missing for these years, there was almost certainly a parallel growth in commitments for petty crimes, particularly vagrancy. The number of vagrants removed northward through the City grew substantially, rising by over 65 per cent, from 385 individuals in 1748 to 626 men, women and children in 1750. Expenditure by the City on vagrant rewards and removals increased even faster; rising from £35 3s. 4d. in 1747 to a new high of £131 11s. 9d. in 1751.

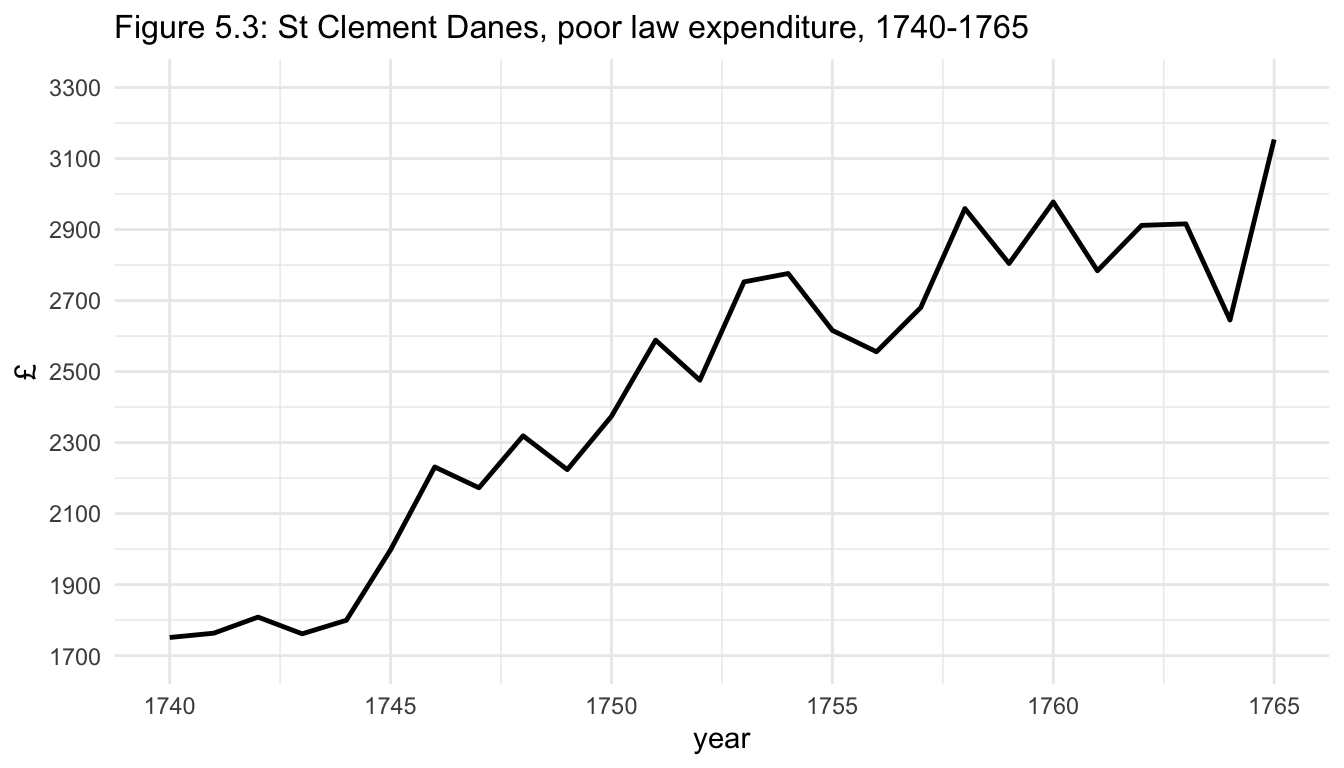

The coming of peace heralded a period of real hardship. A fall in real wages came first: from 1745 to 1749 real wages fell substantially before temporarily levelling out. Subsequently, the arrival of demobilised sailors and soldiers (40,000 by October 1749) increased unemployment. Increasing demand for relief led to a gradual increase in its cost; in Middlesex the years from 1748 to 1750 saw total expenditure rise from £79,181 in 1748 to £82,092 two years later. Similar data for the following years are not available, but records for individual parishes suggest that for many this increase became more dramatic during the 1750s. In St Clement Danes, for example, after remaining relatively stable at between £2,100 and £2,300 per year from 1746 to 1750, expenditure grew rapidly after 1750, reaching £2,977 in 1760.

Reform and the anxieties that drove it were shaped by expectations of the behaviour of the poor and the criminal. Anticipated fears of a crime wave by demobilised soldiers and sailors meant that violent thefts received disproportionate attention in the press, accounting for half of all crime reports in the newspapers. The result was that at the Old Bailey theft with violence accounted for a growing proportion of all prosecutions (rising from 3.8 per cent of all offences in 1747 to 13.0 per cent in 1750). At the same time, we cannot dismiss the possibility that the amount of actual crime committed, driven by the real hardship of the demobilised, unemployed and low paid, did increase. Certainly growing demands for, and expenditure on, poor relief had a substantive basis in the needs of individual men and women; and while costs rose and fell with the price of grain, the overall trend was upwards. Poor relief was more ‘demand led’ than was criminal justice. In between, sharing characteristics of both crime and poverty, vagrancy encompassed both immediate responses driven by perceptions of a problem and changes in the actual life experiences of the poor. It was the combination of the real pressures generated by poverty and crime and the distinctive character of elite perceptions of these problems which shaped the ensuing responses. In turn, the actual impact of these new initiatives was significantly influenced by the responses of plebeian London.

The celebrity highwayman

One of the ways in which criminals actively shaped the distinct and growing anxiety about their activities can be found in the audacious, publicity-seeking practices of some highwaymen. Amplified by newspapers and other publications that were always keen to retail ‘true crime’ to a paying audience, accounts of robberies called attention to the apparent impunity with which crimes were committed, while raising the even more alarming possibility that, owing to the sympathetic manner in which they were portrayed, elite Londoners were not fully committed to bringing these criminals to justice. In the past, in addition to individual publications, highwaymen had taken advantage of the sympathetic attitudes of the publisher of the Ordinary’s Accounts to get their story told. However, following the appointment of a new publisher of the Accounts in 1745 and a new Ordinary, John Taylor, in 1747, the Accounts became more closely guarded against attempts by criminals to justify themselves to the public. Instead, they relied much more heavily on separately published criminal biographies. Between 1747 and 1754, the lives of at least ten English (primarily London) highwaymen were published in separate printed pamphlets; in some cases in more than one version. Six of these lives were purportedly written by the robbers themselves, or at least compiled on the basis of information provided by them. While the criminal voices found in these pamphlets were certainly mediated, publishers went to great lengths to certify their authenticity. Readers of the Memoirs of Dennis Neale, for instance, were invited to view Neale’s original manuscript at the printer’s. Priced at between 2 pence and 1 shilling, these pamphlets were available to a broad reading public, and they were popular. Several were published in multiple editions; those of William Parsons and Dennis Neale went into three editions within a year, while there were eleven editions of The Discoveries of John Poulter in just the first two years after publication.

By retailing ‘intrigues’, ‘extraordinary adventures’ and ‘pranks’, these biographies provided light-hearted entertainment at a time of anxiety about violent crime. William Parsons, hanged at Tyburn in February 1751 for returning from transportation following his arrest for highway robbery, was described in his Memoirs as ‘perhaps as great a Genius for Tricking as any Man in the World’, and the Memoirs’ publication was justified on the grounds that ‘the artful manner he supplied himself from several young Ladies in Newfoundland, deserves the Publick’s Notice’. The text itself consisted largely of tales of his amorous adventures, rather than his crimes, the violence of which was markedly underplayed (’he robb’d several People, but always in the Night … but as nothing remarkable happened during these robberies, it is immaterial to give a Detail of the particular Circumstances’).

Highwaymen used these pamphlets as a form of self-justification, and a means of defending their reputations. Parsons claimed he had been denied support from his wealthy father, creating an ‘errant necessity that urged him to [rob] for a subsistence’, while others, including Thomas Munn, John Hall alias Rich, and William Farrer, claimed they had been corrupted by the bad influence of others, and/or that the robbery for which they had been condemned was their first and only offence. Others, particularly Nicholas Mooney and Matthew Lee , claimed to have been reformed following their arrests. Lee was the subject of a biography attributed to John Wesley in which he repented all his sins following a conversion experience. Even this tale of apparent redemption was subject to spin. While Lee’s biography claimed he pleaded guilty at his trial because he refused to lie following his conversion, in fact his plea was not guilty.

More subversively, as in the 1720s, some highwaymen justified their crimes as acts of social justice, claiming they were prompted by the ‘necessity’ of maintaining their alleged gentlemanly status, and that their actions were no worse than the crimes of their social superiors. Some of these legitimising notions date from before the ideal of the ‘gentleman highwayman’ was first articulated. But that they remained current at mid-century can be seen in the ballad The Flying Highwayman, which celebrated the exploits of ‘Young Morgan’, ‘a flashy blade’, with both social aspirations and a social conscience:

Soon he became a Gentleman,

And left off driving Asses.

I scorn poor people for to rob,

I thought it so my duty;

But when I met the rich and gay,

On them I made my Booty.

Morgan is arrested and sentenced to die, but like Macheath in the Beggar’s Opera, he is reprieved at the last minute.

The mixed messages about robbery disseminated at this time are most fully embodied in publications about the most famous highwayman of this era. James Maclaine largely succeeded in portraying himself as a gentleman, with the Gentleman’s Magazine reporting that he ‘had handsome lodgings in St James’s Street, at two guineas a week, and passed for an Irish gentleman at £700 a year’; the newspapers described him as ‘genteel’. Even before Maclaine emerged into the limelight following his arrest, his social aspirations were evident in the letter he wrote to Horace Walpole following his robbery of Walpole in Hyde Park in November 1749, during which Maclaine’s pistol was accidentally fired. Written on gilt-edged paper (but poorly spelled and ungrammatical), the letter assured Walpole that no harm had been intended and justified the crime and the ransom he demanded for the return of Walpole’s watch and seals on the grounds that ‘we Are Reduced by the misfortunes of the world and obliged to have Recourse to this method of getting money’, before promising to repay the small sum taken from Walpole’s footman. Similarly, when Maclaine and his accomplice William Plunket robbed the Salisbury coach, the crime for which Maclaine was arrested and tried, the two robbers made a great show of acting ‘politely’ and once again claimed ‘that it was necessity [that] forced them upon those hazardous enterprizes’. Plunket put away his pistol in order to reassure the passengers, and, ‘for fear of frightening the Lady, without forcing her out of the coach, took what small matter she offered without further search’.

Following his arrest Maclaine achieved celebrity status by playing to the gallery during his preliminary examination and at his Old Bailey trial, thereby obtaining the attention of the press. Portraying himself as a gentleman who had fallen on hard times, he evoked the tears of watching gentlewomen and men, obtaining both their sympathy and their financial support. By actively manipulating the public presentation of his case and his person, and through an account of his behaviour in prison penned by a sympathetic dissenting minister, he shaped the representation of his story and successfully generated widespread sympathy. Some of his victims, including Horace Walpole and Lord Eglington, refused to testify against him in court (and were praised for doing so). And at least nine ‘gentleman of credit’ and some ladies provided character witnesses at his trial. The Sunday following his conviction 3,000 people visited him in prison, and Horace Walpole commented that ‘you can’t conceive of this ridiculous rage there is of going to Newgate’. Some of his elite visitors apparently attempted to secure him a pardon, but they were unsuccessful.

Not everyone was taken in. The case prompted concern that the popularity of gentlemen highwaymen was subverting attempts to crack down on robbery during the post-war crisis. As John Taylor, Ordinary of Newgate, observed of Maclaine:

though he has been called the Gentleman Highwayman, and in his Dress and Equipage very much affected the fine Gentleman, yet to a Man acquainted with good Breeding, that can distinguish it from Impudence and Affectation, there was very little in his Address or Behaviour, that could entitle him to that Character.

Similarly, A Genuine Account of the Life and Actions of James Maclean, Highwayman, a pamphlet written with the express purpose of seeing him hanged, complained that ‘he has so far wrought himself into the esteem of persons of rank, that they have not only been induced to contribute to support him, but to solicit and use their utmost effort to save him’, when in fact ‘by the laws of this country he is undoubtedly to be deemed an enemy to society’. Even Horace Walpole, one of his most sympathetic victims, was moved to observe that ‘his profession is no joke’.

In short, at the same moment that the wave of prosecutions which followed the peace in the autumn of 1748 signalled rising anxieties about violent crime, the activities of the ‘gentlemen of the highway’ evidenced continuing sympathy for a particular type of robber. This ambivalence could not be allowed to remain unchallenged. As Fifield Allen observed, ‘robberies were so frequent, committed too by people of a genteel appearance like his’, that Maclaine and others like him simply had to be hanged. In one biography of the highwayman and robber William Parsons, the author felt obliged to defend the decision to prosecute him for returning from transportation, observing that bringing him to justice was ‘absolutely necessary for the safety of the community’. That this point even needed to be made suggests just how effective the self-presentation of these highwaymen had become. The publicity they achieved contributed to the growing sense of moral panic among the authorities, forcing them to develop new strategies to address the problem.

Henry Fielding’s great plan

At the centre of the post-war response to crime was Henry Fielding, already a well-known dramatist and novelist and, from 1748, an active and ambitious justice of the peace. Fielding was already serving as a publicist for the government in 1748 when his patron the Duke of Bedford secured his appointment as justice of the peace in Westminster, and following Bedford’s assistance in meeting the £100 property qualification, in Middlesex the following January. As Fielding told Bedford, ‘without this Addition [appointment to the Middlesex bench] I can not completely serve the Government in that Office’. From December 1748 Fielding was living in Bow Street, in the house formerly occupied by Thomas De Veil, and, like De Veil, he became ‘court justice’, the leading metropolitan justice charged with providing advice and support to the government, particularly on politically sensitive issues. As Malvin Zirker remarks, he was ‘a political appointee whose voice could never be entirely his own’.

Fielding hit the ground running immediately after he took the oath of office in January 1749. In March he was elected chairman of the Westminster sessions, and his first charge to the grand jury was delivered in June and published in July. Fielding’s ideas about poverty and crime are best known from his social policy writings, but these were informed by his day-to-day work at Bow Street. Evidence of his extensive judicial activity can be found not only throughout the Middlesex, Westminster and Old Bailey sessions records but also through his attempts at self-publicity, in reports he planted in newspapers such as the Public Advertiser and Whitehall Evening Post, and most substantially in his own Covent Garden Journal, published between 4 January and 25 November 1752. According to his more sympathetic biographers, Fielding ‘exercised as much latitude as possible under the law’ and ‘temper[ed] justice with mercy’, occasionally discharging or bailing prostitutes and petty thieves rather than committing them to prison, and sometimes relieving beggars rather than punishing them. Fielding certainly promoted this sympathetic view of his judicial practice, later suggesting that, unlike ‘trading justices’, his object was ‘composing, instead of inflaming, the quarrels of porters and beggars’, and claiming that he generally refused ‘to take a shilling from a man who most undoubtedly would not have had another left’.

Yet there was a darker side to Fielding’s activities. He did show real sympathy for some young girls seduced into prostitution, as when he described the case of Mary Parkington in the Covent Garden Journal: she was ‘a very beautiful Girl of sixteen Years of Age’ who was ‘seduced by a young Sea-Officer’ and taken to a brothel run by Philip Church. However, his role was compromised by exposing her name and circumstances in print, thereby destroying her reputation. Moreover, any sympathy Fielding may have shown for petty offenders was balanced by his merciless pursuit of more serious criminals. He led numerous raids against what he believed were ‘gangs’ of street robbers, highwaymen and housebreakers, including the ‘Royal Family’, led by Thomas Jones alias Harper in 1749, and worked tirelessly to ensure their conviction and execution. Fielding also created the Bow Street Runners as an effective tool in his campaign against felons.

It is the severely judgemental side of Fielding’s judicial personality which shines through in his social pamphlets. Despite the inclusion of many ‘low’ characters and scenes of licence in his fiction (including Tom Jones, published in February 1749, just as he began work as a justice), and the complicated and heart-breaking stories he heard on a daily basis at Bow Street, there is a noticeable lack of ‘irony and ambivalence’ in his other writings. In his widely read pronouncements on social policy, it was his role as a political appointee and self-appointed ‘censor’ of metropolitan morals that came to dominate.

Famously addicted to chewing tobacco, profligate with his own money and that of his friends, gout-ridden from decades of self-indulgence, Henry Fielding knew precisely where the blame lay for the ills of society. He argued that the perfect ancient balance of the English constitution had been corrupted by the ever-growing luxury and power of the poor. He lay responsibility for the problems faced by London squarely at the feet of ‘the mob’; of that ‘very large and powerful body which form the fourth Estate in this Community’, whose ambitious powers he believed extended to securing control over the execution of the laws, ‘particularly in the Case of the Gin-Act some Years ago’, and to ‘stifling’ the activities of informers. In his most substantial work on social policy, An Enquiry into the Causes of the Late Increase in Robbers, published in 1751 at the height of the post-war panic over violent crime, he detailed how the ‘Dregs of the People’ had been transformed: ‘The narrowness of their Fortune is changed into Wealth; the Simplicity of their Manners into Craft; their Frugality into Luxury; their Humility into Pride, and their Subjection into Equality.’ In Fielding’s view, this doleful corruption, made possible by high wages, was manifest in their attendance at plays (some of which Fielding himself had written), pleasure gardens and masquerades, and in gin drinking and gambling; all of which led to crime via moral and financial bankruptcy. Moreover, Fielding believed the poor’s ‘wandering habits’ placed them beyond the oversight of the magistracy. The ‘mob’ needed to be brought to heel and disciplined to unrelieved labour: ‘throwing the Reins on the Neck of Idleness’.

Fielding undoubtedly had a ‘conservative social outlook’, and many of his solutions were the nostrums retailed in social welfare pamphlets published over the preceding two centuries. However, there are two facets of Fielding’s writings that are distinctive. First, he constantly and self-servingly emphasises the role of the justice of the peace and the county bench as the layer of government to be entrusted with additional responsibility. Almost all of Fielding’s solutions to social disorder involved shifting large amounts of power and expenditure from the parishes to the bench. And second, he takes an unusually draconian approach in advocating changes that would undermine the rights of defendants in court, and the poor to freedom of movement. He sought to reform the major systems of the social policy state – poor relief, felony prosecution and vagrancy – to ensure that those whose place it was to labour would suffer their poverty without cavil or complaint and without recourse to begging or theft.

The earliest clear statement of the remedies Fielding advocated can be found in the draft of a bill he submitted to the Lord Chancellor, Philip Hardwicke, in 1749, some six months after he took up his role as ‘court justice’. The bill advocated the creation of a ‘commission’ of justices empowered to oversee the night watch, and, if implemented, would have enhanced the powers of watchmen by providing them with arms and authorising them to arrest anyone found with a ‘dangerous weapon’, as well as ‘all suspicious Persons … standing in the streets Lanes or bye allys’. Two years later, in 1751, Fielding extended his analysis and his solutions in the Enquiry, before rounding off his consideration of poverty and crime with his Proposal for Making an effectual provision for the Poor, published in 1753.

Although historians have concentrated on his attitudes to policing and crime, the majority of Fielding’s published work on social policy focused on the interwoven issues of poverty and vagrancy. He felt the main weakness in the system of poor relief lay in the inadequacies and failures of parish officers, who had neglected their legal obligation to set the poor to work, and proposed a ‘county house’ able to accommodate 5,000 people, where the able-bodied and unemployed were to be set to work, while the vicious and workshy would be put to hard labour in a new ‘county house of correction’, able to imprison and set to hard labour some 600 vagrants. And to make this pabulum of oppression work, he outlined a revision of the system of settlement and certificates to ensure that all migratory poor were subject to universal enforced labour, and advocated beefing up the laws against vagrants to ensure they received appropriate corporal punishment. None of these proposals was new, but Fielding’s combined workhouse and house of correction did mark a new high point in relation to size and levels of complexity. It prefigured even the largest of nineteenth-century institutions and, if created, would have given the Middlesex bench an unprecedented budget and staff.

While poverty and vagrancy were the main focus of Fielding’s pamphlets, he also included substantial proposals for the reform of arrest, felony prosecution and execution. Here Fielding was slightly more innovative, although he was ‘preoccupied with the repressive aspects of penal policy’. Receivers of stolen goods were to be prosecuted even when the thief was acquitted; justices were to be given new powers to arrest suspicious persons; greater weight was to be placed on the role of pre-trial examination and interrogation; and in court the evidence of accomplices was to be given precedence over that of character witnesses. And once a defendant had been convicted, Fielding wished to limit the role of the royal pardon and to shift the place of executions from Tyburn to just outside the Old Bailey, and to conduct them in private as a means of eliminating the carnivalesque character of hanging days. Overall, he sought to make executions quicker, more certain and more terrible.

Henry Fielding’s great plan, including armed watchmen, forced labour for the poor and more frequent judicial murders, overseen by an increasingly powerful bench of magistrates, exemplifies one important strand in the thinking of elite Londoners in response to the post-war crisis and encompasses a set of ideas which would inform the evolution of social and criminal policy for the rest of the century. In the short term, its importance can be seen in the publishing success of the Enquiry – the first printing of 1,500 copies sold out quickly and a second of 2,000 was available within three weeks. It was ‘more frequently cited than any other social pamphlet during the early fifties’. But Fielding had his critics among Londoners of all social classes. While the long-term influence of his ideas on the evolution of policy was substantial, their direct and short-term effect was much more limited. His reputation was undermined by his involvement in two scandals which raised questions about his competence and independence as a justice: the execution of Bosavern Penlez in 1749 and the Elizabeth Canning case four years later.

In early July 1749 thousands of sailors destroyed brothels on the Strand after two of their number had been robbed in one of the houses, but it was Fielding’s zealous defence of the decision to execute one of the rioters which turned a traditional riot into a major crisis. After a superficial examination of the first prisoners arrested (while a mob gathered outside his door), Fielding committed them to Newgate prison. Ultimately only three of the rioters were tried at the Old Bailey the following September, charged with violating the 1715 Riot Act. In spite of questionable prosecution evidence (one witness declared ‘Upon my word … for my part I would not hang a dog or a cat upon their evidence’) and good character references, two men were convicted: John Wilson and Bosavern Penlez. Though the jury recommended mercy, both were sentenced to death. These sentences provoked widespread outrage: there was substantial sympathy for the rioters’ aims (destruction of the brothels), and it was felt both Wilson and Penlez (a journeyman shoemaker and perukemaker respectively) were men of good character who had been accidentally caught up in the riots. A substantial petitioning campaign led to a last-minute pardon for Wilson, but Penlez was hanged.

Even before the execution, Fielding was criticised for his role in the case, with some even suggesting that he was protecting the brothels because he accepted bribes from their owners. More damning, however, was the evidence that later emerged of his role in ensuring Penlez was refused a pardon. It was alleged that Penlez had originally been arrested in possession of a bundle of linen taken from one of the brothels, and although he had been indicted for burglary he had not been tried for this offence at the Old Bailey. At the last minute Fielding brought evidence of the theft to the attention of the Privy Council, and against the backdrop of the crime wave, Penlez’s fate was sealed. Fielding’s behind-the-scenes role became public when he published his True State of the Case of Bosavern Penlez in November, where he claimed, to his ‘satisfaction’, that his lobbying was responsible for the decision to pardon Wilson ‘as an Object of Mercy’ and execute Penlez as ‘an Object of Justice’.

The execution of Penlez proved to be crucial in the following month’s Westminster by-election, which the government very nearly lost. Westminster had a broad franchise and a history of radical politics, and was both one of the most important and one of the most fiercely contested parliamentary constituencies in the country. The opposition candidate in 1749, George Vandeput, represented a faction which styled itself the ‘Independent Electors of Westminster’, and his supporters were typically middle-class householders of the sort who had opposed reforms of the night watch and defended open vestries in the preceding decades. In contrast, Vandeput’s opponent, the court candidate Granville Leveson-Gower (Viscount Trentham), supported by Fielding, was tarred by his role in the Penlez affair (having failed to support the campaign for a pardon). Penlez featured frequently in the opposition’s election literature, and his ghost even appeared in a procession, in which ‘he frequently sat up and harangued the populace for his unhappy fate’. Some of Vandeput’s strongest support came from the parishes where the brothels were located and the Penlez riots took place: St Clement Danes, St Paul Covent Garden and St Martin in the Fields. Allying themselves with the sailors who attacked the brothels, these voters joined the public demonstrations in Vandeput’s support. Worryingly for Fielding, these were the very parishes most directly served by his Bow Street office.

In the end Trentham narrowly won the election, but the events of that autumn led the Duke of Richmond, Sir Thomas Robinson, to worry about the increasing powers of the mob:

I think in all future Elections the power of the Court is weakened & the lower Class of voters will determine Victory which ever side they take … [they] will be influenced from popular Cryes or Caprice or Money, for when we see what … Penley’s Ghost has done at this Juncture, can any Juncture be without Scarecrows of such base materials[?]

Four years later Fielding embroiled himself in another very public controversy, this time over the validity of the claims by Elizabeth Canning that she had been kidnapped and held prisoner in a house of ill repute for four weeks. Canning’s claim initially resulted in the conviction of Mary Squires and Susannah Wells for robbery. But eventually this verdict was overturned, and Canning herself was convicted of perjury. The dispute over the truth of Canning’s claims led to a major pamphlet war and debate in the newspapers lasting several months; the essayist Allan Ramsay claimed it was ‘the conversation of every alehouse within the bills of mortality’. This case has attracted substantial scholarly interest, but not enough attention has been paid to the damage to Fielding’s reputation caused by his role in coercing Virtue Hall into testifying against Squires and Wells in the original trial, testimony which she later recanted, leading to the trial of Canning. Once again, Fielding’s attempts to defend his actions in print only exacerbated the situation.

Fielding was a divisive figure, and his behaviour in the Penlez and Canning cases, when combined with his aggressive approach to the office of justice of the peace, stimulated opposition. He was caricatured for ‘his stern and arrogant demeanour on the bench, his habit of declaiming with his jaws crammed with tobacco, his way of favouring the rich and great while bullying the lower classes’. As a result of these very public challenges to his authority, some of those who were summoned to appear before him were energised to fight back. In his early days as a justice, following the Penlez riot but before his execution, some defendants incarcerated on Fielding’s warrants challenged their commitments under the Habeas Corpus Act, including Samuel Cross. Fielding committed Cross to prison following a brawl in which James Burford died, but Cross petitioned ‘that he may be either Tryed Bailed or Discharged’ for ‘the Said Supposed offence Pursuant to the Direction’s of the Habeas Corpus Act’. The following year Charles Pratt was more successful when, after he was accused of stealing a mourning ring and committed by Fielding to New Prison, he protested his innocence and lodged a similar petition (he was not tried). In the next two years at least seven appeals were launched against Fielding’s summary convictions, including those by four scavengers, who claimed their prosecution for not fulfilling their duties was itself ‘illegal’, and by Israel Walker, a housekeeper and dealer in brandy and other spirituous liquors. Committed by Fielding to the house of correction as a ‘Rogue & Vagabond’, Walker claimed he had been ‘unjustly charged’ with breaking a watchman’s lantern and playing at unlawful games. These challenges to Fielding’s authority may have provided him with additional motivation for reinforcing his powers through the promotion of the Bow Street Runners, but they may have also contributed to the popular opposition they encountered.

Parliament’s response

Two days before the publication of Fielding’s Enquiry, the king addressed the issue of rising crime and disorder in his speech opening parliament on 17 January 1751, exhorting the Lords and Commons ‘to make the best use of the present state of tranquillity … for enforcing the execution of the laws, and for suppressing those Outrages and Violences, which are inconsistent with all good Order and Government’. In response, the Commons set up a committee (the ‘Felonies Committee’), to investigate ‘the Laws in being, which relate to Felonies, and other Offences against the Peace’. Six weeks later their remit was extended to ‘the Defects, the Repeal, or Amendment of the Laws relating to the … Poor’. This committee was the first ‘national, central investigation into the issue of crime and justice as a whole’ ever conducted, and it was all the more remarkable for considering the issues of poor relief and settlement in the same report. And yet the legislation which resulted was of limited consequence. Owing to both elite opposition and anticipated plebeian resistance to more ambitious measures, and actual plebeian opposition to the implementation of the statutes that were passed, the aspirations of the committee were not realised.

The committee worked fast and in April reported a series of twenty-five resolutions identifying the defects of the laws concerning criminal justice; adding a further two substantive resolutions on poor relief in June. The most remarkable feature of these resolutions is that, like Fielding’s Enquiry (which had little direct influence on the committee’s findings), the responsibility for crime and poverty was placed firmly on the lower class, and measures were proposed to give magistrates greater control over ‘suspicious’ characters. According to the committee, both ‘the Increase of Thefts and Robberies of late’ and the recent increase in the expense of poor relief resulted directly from the ‘Habit of Idleness, in which the lower People have been bred often from their Youth’. The committee went on specifically to blame ‘the Multitude of Places of Entertainment for the lower Sort of People’ and ‘Gaming amongst the inferior Rank of People’ as ‘incitement[s] to theft’, before identifying the failure of the system of legal ‘Settlement’ to prevent the poor from wandering and poor parenting for propagating ‘a new Race of Chargeable Poor, from Generation to Generation’.

This was a good time for domestic legislation. It was peacetime and the government had firm control over the House of Commons. However, in comparison with the breadth of the committee’s recommendations, the legislative result was minimal, as ‘the seamless web’ of resolutions was chopped ‘into legislative rags’ and its radical poor law proposals were simply ignored. In part this reflects the impediments to law making at this time, but it also reflects the specific pressures under which MPs were working. Not only were there concerns about the costs of implementing new legislation, and its impact on the vocal and competing interests of the parishes, counties, the City of London and justices of the peace, but MPs also anticipated that new measures would be subverted by plebeian opposition. This was particularly relevant in the case of the dockyards hard labour bill. Nonetheless, three important statutes were passed: the Gin Act (1751), Disorderly Houses Act (1752) and Murder Act (1752).

The 1751 Gin Act did not emanate from the work of the Felonies Committee, but it was a product of the same reforming impetus. The bill was discussed in the whole house the same day the recommendations of the Felonies Committee were presented, and it addressed many of the same issues. Following the passage of the 1743 Gin Act, overall consumption of gin had been stable. Concern among reformers about its deleterious effects had nonetheless continued, and the perception of a post-war crime wave gave reformers a new opportunity to make their case. ‘The strategy’, as Patrick Dillon argues, ‘was to tie gin-drinking in with the crime wave’. In a coordinated campaign starting in early 1751, parliament was besieged by pamphlets and petitions, making arguments familiar from the 1730s that excessive drinking by the lower class was responsible for a spate of social problems.

Fielding’s was the first high-profile intervention. In section two of his Enquiry, he identified drunkenness as a key manifestation of the problem of the ‘Luxury of the Vulgar’, because it led to ‘so many temporal Mischiefs … amongst which are very frequently Robbery and Murder itself’. A fortnight later, Isaac Maddox, the Bishop of Worcester, published a sermon, The Expediency of Preventive Wisdom, which made similar arguments, but paid more attention to gin’s role in infant mortality while also arguing that if successful, plebeian resistance to the Gin Acts would lead to social levelling. As if on cue, Hogarth’s Gin Lane followed a fortnight later, with its evocative image of poverty, chaos and death juxtaposed with the order and respectability of Beer Street.

Despite Hogarth’s professed ambition to use his prints to reform the poor directly, the real point of these prints and pamphlets was to bring the problem to the attention of parliament and those responsible for governing London. In this they succeeded: London’s parish vestries, along with the Cities of London and Westminster and the Middlesex sessions, were prompted to petition parliament. The minutes of the vestry of St Clement Danes reveal that this was an organised campaign: the vestry met on 4 March to ‘to take the Opinion of the Inhabitants whether they will Join with the rest of the Inhabitants the City and Liberty of Westmr. in presenting a Petition to Parliament to Suppress the too common use of Spiritous Liquors’. The motion was ‘Carried in the Affirmative Nem Con’.

When combined with extensive coverage in the press, the pressure on parliament was substantial. And yet the ensuing bill was modest in its ambitions. The Act, against ‘the immoderate drinking of spirits amongst the meaner and lowest sort’, is generally perceived as having finally solved the gin problem, bringing to an end more than two decades of legislative failure. However, the extent of its impact is debatable, and the reasons for the lack of popular opposition to the bill, when compared to the resistance which led to the abandonment of attempts to enforce the 1736 Act, need to be considered.

Cognisant of the failure of previous bills, the Act targeted those who were most able, and likely, to comply, while avoiding mechanisms for enforcement which were likely to generate popular opposition. Its provisions, described by Horace Walpole as ‘slight ones indeed for so enormous an evil!’, meant that it stopped far short of total prohibition. As Patrick Dillon observes, ‘there were plenty of politicians and commentators who could remember the lesson of 1736’. Distillers were required to pay a substantially increased excise duty (up 4.5 pence a gallon) and prohibited from retailing gin, and retailers had to pay a higher licence fee (£2), while street selling remained prohibited. However, while informers, whose activities had provoked so much opposition in 1736, could still be used against retailers who sold gin without a licence, they were not given, as they were in 1736, any significant financial inducement to do so. Consequently, the Act led to few prosecutions.

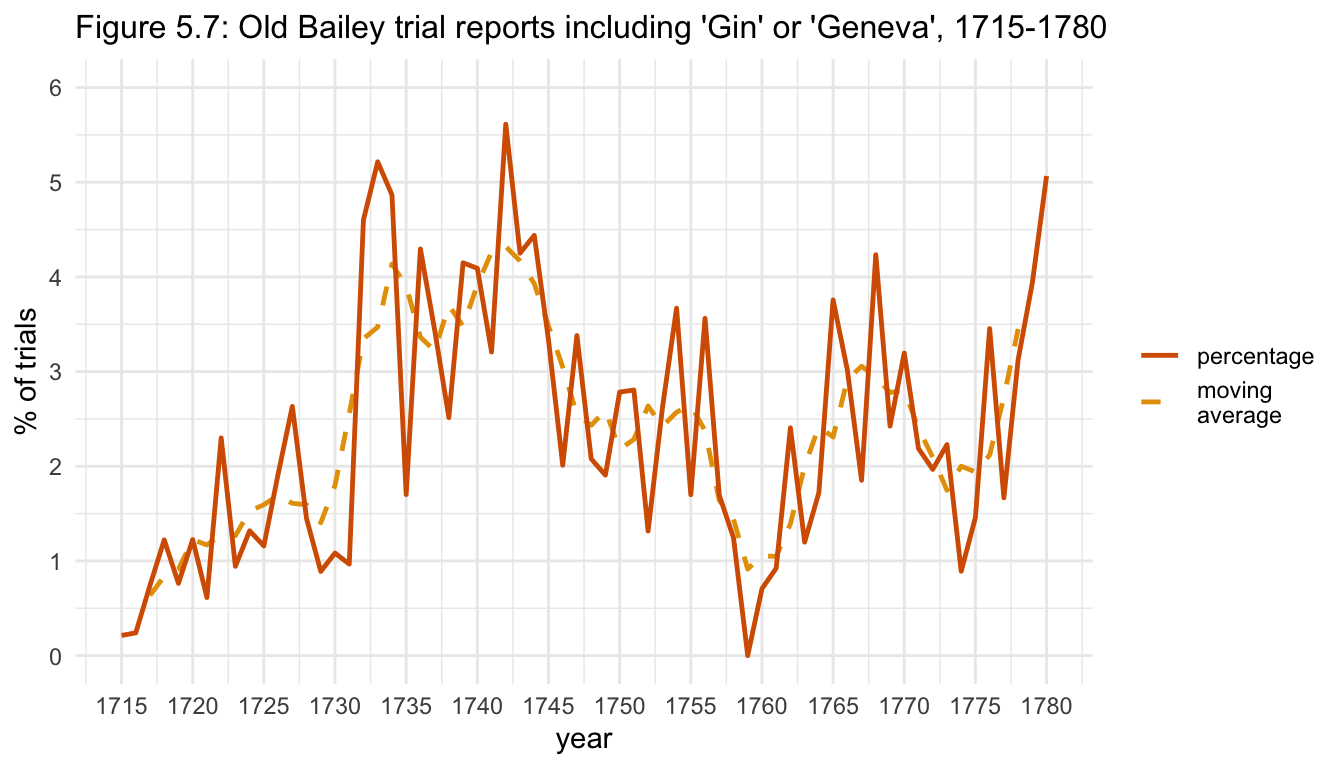

Measured by levels of production, gin drinking fell in 1752 by over a third, but as with previous acts, levels of consumption rapidly recovered. Gin remained part of the daily life of plebeian Londoners. The number of trials at the Old Bailey in which ‘gin’ and/or ‘geneva’ is mentioned, as a stolen good or a drink consumed by the defendant and/or victim in the lead up to a crime, remained stable, averaging 11.7 a year under the 1743 Gin Act (1744–50) and 10.6 following the passage of the 1751 Act (1752–6). While, as a result of the growing number of trials heard in the 1750s, the percentage involving ‘gin’ or ‘geneva’ fell from a peak in 1744, gin recovered its role in the records of crime in the 1760s and 1770s (Figure 5.7). In their biographies of the condemned, the Ordinaries of Newgate continued to represent gin drinking as a lower-class curse: Hannah Wilson, convicted in 1753 of stealing a coat and ribbon from a child, ‘had been drinking that cursed Liquor, called Gin, and was drunk, or she had never have attempted to use the poor Baby ill’. Following the harvest failures of 1756–7 and a temporary ban on the domestic production of spirits, gin drinking declined temporarily, but judging by the frequency of mentions in Old Bailey trials, it soon recovered. Overall consumption did eventually decline, but this was due to the fact the price of gin had risen and an alternative, cheaper, drink (porter) became available. As Nicholas Rogers argues, ’the gin epidemic was ultimately contained by changes in consumer taste, not by regulation’.

Source: Old Bailey Online, keyword search. The total number of trials per year was calculated by William Turkel using the Old Bailey Online API.

Online dataset: Gin/Geneva in Old Bailey Trials (xlsx)

The two Acts passed in the following year in direct response to proposals from the Felonies Committee were also targeted at, and in some respects shaped by, plebeian London. The first, ‘A Bill for the better preventing Thefts and Robberies; and for regulating Places of publick Entertainment; and punishing Persons keeping disorderly Houses’, better known as the Disorderly Houses Act, contained a number of measures intended to make felonies easier to prosecute, in addition to specific measures targeted at ‘disorderly houses’. These were thought to harbour gaming, prostitution and excessive drinking, vices that were considered to lead ineluctably to more serious crime. Consequently, houses that provided ‘Publick Dancing, Musick, and other public Entertainment of the like kind’ within twenty miles of London would require a licence, which could only be granted by four or more justices of the peace, and anyone keeping an unlicensed house could be fined £100. Prosecution of ‘disorderly houses’, including ‘bawdy houses’ and ‘gaming houses’, was made easier by rewards paid to informers, and a legal injunction requiring constables to act on the complaints they received (their expenses were paid).

Like the Gin Act, the Disorderly Houses Act was specifically targeted at the poor. The measures were justified on the grounds that a

Multitude of places of Entertainment for the lower sort of People is a … great Cause of Thefts and Robberies, as they are thereby tempted to spend their small Substance in riotous Pleasures, and in Consequence are put on unlawful Methods of supplying their Wants, and renewing their Pleasures.

The Act was also designed to close various loopholes that had allowed the owners and operators of such houses to evade prosecution, as had occurred during the attempts to close down disorderly houses in the 1730s. It outlawed the common strategy of removing a case by a writ of certiorari to the Court of King’s Bench, which added substantially to the cost of a prosecution. The Act also closed the loophole which had allowed owners to evade prosecution by ensuring that they were not directly connected with running them.

There is little evidence that the Act had any real impact. In the short term, some pleasure gardens appear to have lost their music licences, and there may have been an increase in the number of presentments against disorderly houses in the City, but from 1753 presentments ‘decline[d] steadily’, since ‘the process of prosecution remained both expensive and time-consuming’. It appears there was little support for the new Act. Even the Gentleman’s Magazine complained that the proposed bill would ‘deny all amusements to the lower ranks of people’, and potentially ‘throw all those now engaged in exhibiting such amusement out of that way of getting their bread’, resulting in an ‘increase [in] robberies, instead of lessening them’. In the end, owing to reluctance to prosecute partly due to concerns about its impact on the poor, as well as anticipated continuing opposition to prosecutions, the Act made little difference, such that later in the decade campaigners against vice found it necessary to launch a new society for the reformation of manners. In 1758, when Justice Saunders Welch complained that owing to ‘the dread and terror every man is under of incurring the odious name of informer’, the Act had failed to close down even the most ‘bare-faced’ brothels. It has been estimated there were only ten to fifteen successful convictions across the whole metropolis. The problem of disorderly houses (and gin) remained in 1768, when John Fielding noted that they encouraged ‘gaming and other disorders’ and that many sold spirituous liquors, ‘of which they vend treble the Quantity they do of Beer, which is absolutely establishing Gin-Shops’. Neither is there any evidence that the provisions of the Act making felonies easier to prosecute had any impact – the number of offences tried at the Old Bailey in the subsequent decade fell by over a third (Figure 5.2).

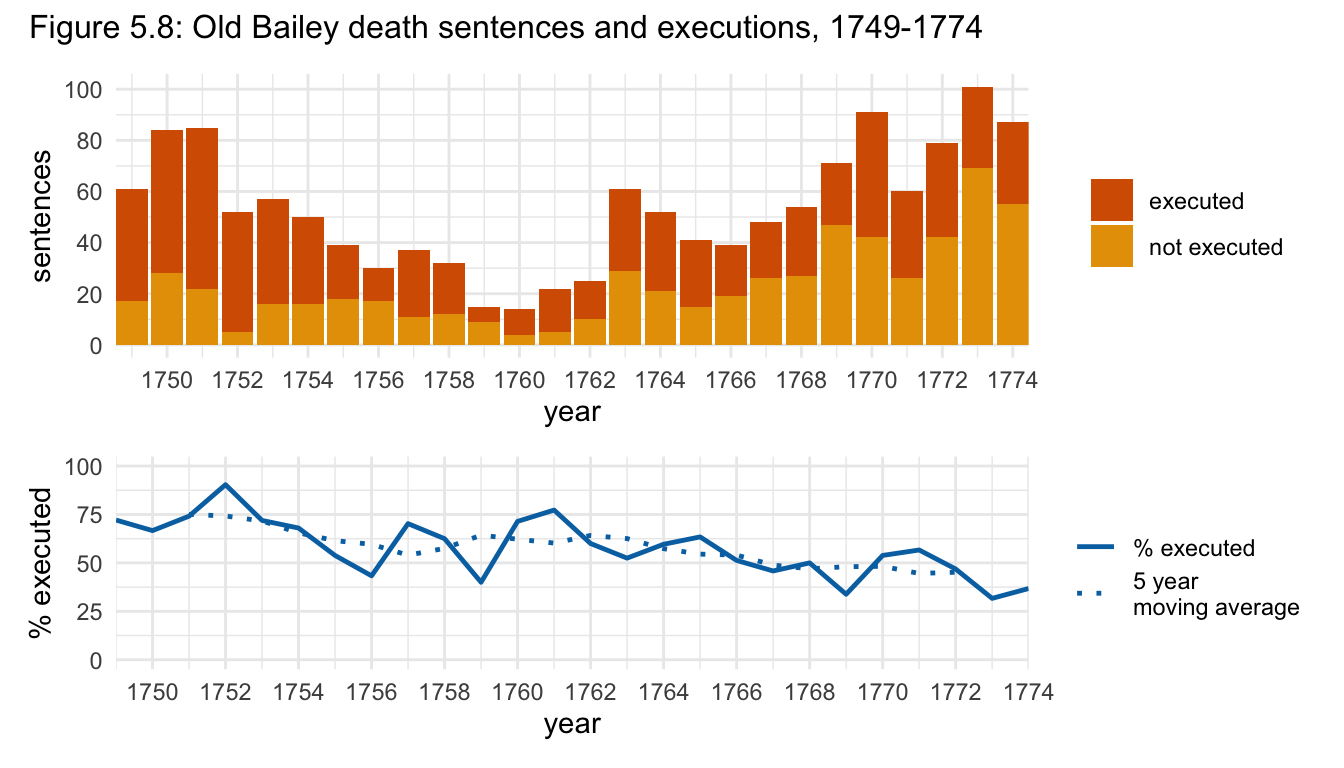

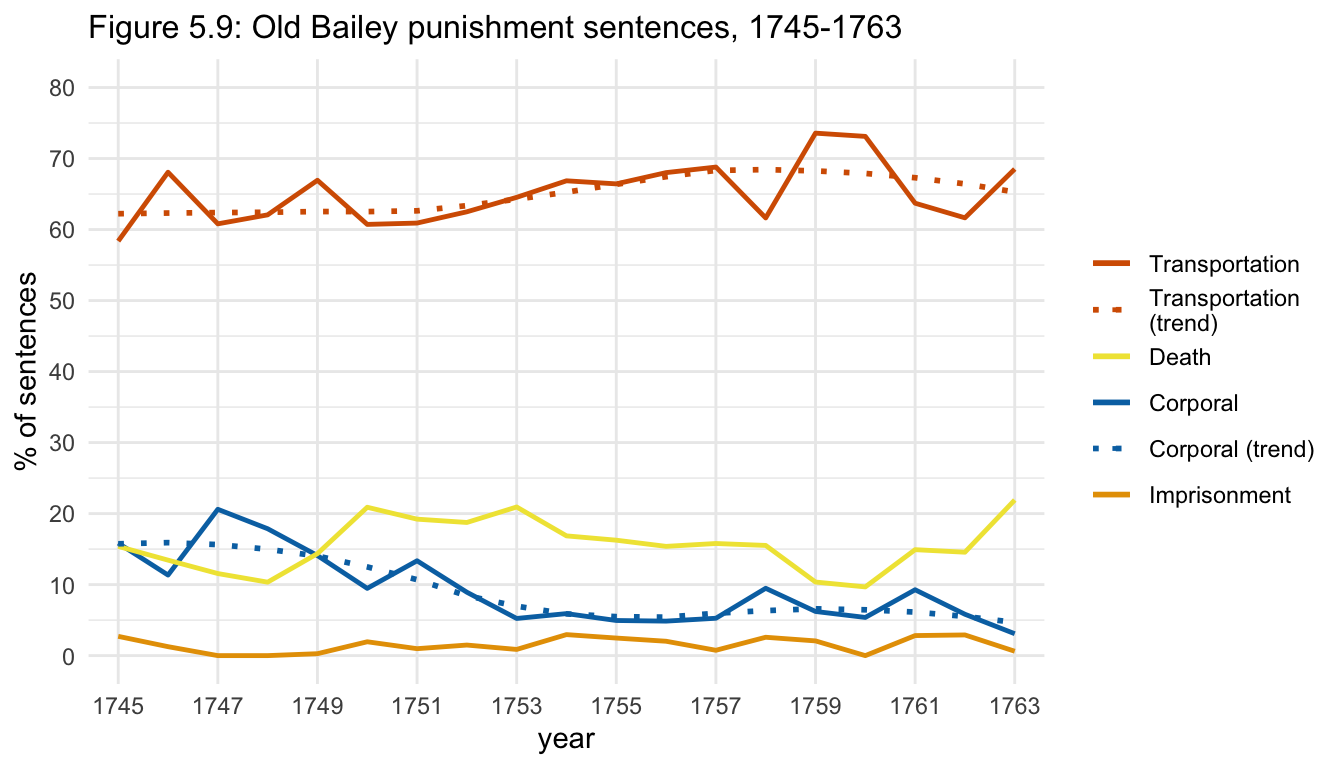

If neither the Gin Act nor the Disorderly Houses Act had any substantive effect on plebeian behaviour, the Murder Act, also passed in 1752, was more successful – at least in as much as it altered penal practice with respect to those convicted of murder. Crowd behaviour at executions also changed, but disorder did not disappear. Although not a direct response to any of the recommendations of the Felonies Committee, the Murder Act was passed with ‘incredible speed’ in 1752, urged on its legislative course by a spate of widely publicised murders, including horrific crimes committed by Mary Blandy and Elizabeth Jefferies, collectively represented in the press as ‘a pressing social problem’. The Act modified the punishment for murder in order to add ‘some further terror and peculiar mark of infamy to the punishment of death’, by ensuring that convicted murderers were executed almost immediately following their conviction (two days later), and that their bodies were either hung in chains or handed over to the surgeons to be ‘dissected and anatomized’. This made execution more certain, as few pardons could be organised in the short space between sentence and execution, and more horrible, by playing on popular beliefs about the significance of keeping the corpse intact. At one and the same time, the Act attempted to reduce disorder at Tyburn while securing a regular supply of fresh cadavers for the dissection tables at Surgeons’ Hall.

In one respect this statute is most impressive for what it did not do. It did not follow the careworn pattern typical of early eighteenth-century legislation of extending capital punishment to a wider range of offences – there was no desire to increase the number of executions. This needs to be understood in the context of the dramatic increase in executions in the years 1749–52, driven by the post-war wave of prosecutions, and the disorder which accompanied them. Despite the presence of strong guards and the sheriffs’ attempts to negotiate with the crowd over control of the bodies of the executed, battles occasionally broke out between the crowd and the surgeon’s men, with sailors and the Irish (who also figure frequently among the executed) prominent in the mêlée, often armed with bludgeons.

The presence of a contingent of foot guards as well as civil officers at the execution in 1748 of former sailor John Lancaster, for example, did not prevent a ‘company of eight sailors with truncheons’ rescuing the body from the surgeons’ men after they left Tyburn and carrying it ‘in triumph through London’. The execution of the ‘Gentleman Highwayman’ James Maclaine, hanged with eleven other men in October 1750, unsurprisingly attracted a huge crowd: ‘the greatest Concourse of People at Tyburn ever known at any Execution’. In the chaos following the day’s executions, the negotiated allocation of the bodies between friends of the deceased and the surgeons broke down. Maclaine’s celebrity status meant that it was impossible to retain his body for dissection (though improbably his skeleton appears in the surgeons’ hall in Plate 4 of William Hogarth’s Four Stages of Cruelty). His body and that of William Smith (convicted of forgery) ‘were taken away by their friends in Hearses, in order to be interred’, while the surgeons were given the body of John Griffith (convicted of highway robbery). However, as the London Evening Post reported, while the bodies of ‘the others, who had Friends or Relations, were taken care of by them’, ‘three or four were suffer’d to be carried off by the Mob, who dragg’d their naked Bodies about’. After six men, including two Irishmen, were hanged in November 1751, the London Evening Post reported that the execution ‘was performed with great Decency and Order’, after ‘a great Number of Sailors, and others, appearing arm’d with Bludgeons, under pretence of rescuing their Acquaintances from the Surgeons’ were disarmed. But this paper failed to report that a battle took place involving ‘near a quarter of a hundred chairmen and milkmen, [who] seemed to be all concerned in taking away the cart [and] horses, with the bodies’ of two of the condemned. The men, including Michael MacGennis, an Irish milkman, had seized the cart in order to carry away the bodies, but the cart’s owner, Richard Shears, resisted, and in an ensuing scuffle Shears was fatally stabbed. Subsequently, MacGennis and his accomplice drove the cart in triumph to Tower Hill, where they exhibited the bodies.

Elite concerns about the disorder at ‘Tyburn Fair’, given renewed impetus by William Hogarth’s representation of Tyburn in Plate 11 of Industry and Idleness in 1747 and by Henry Fielding’s comments in his Enquiry four years later, were not without foundation, though they failed to understand plebeian motivations. Both forcibly suggested that the death penalty was not working because spectators had come to treat executions as a form of entertainment and were not learning the right lesson. Instead of recognising the consequences of sin, the terror of the gallows had become, in the words of another commentator, subject to ‘the ridicule and mockery of an audacious vulgar’. Contemporaries worried that at best the crowd treated executions as a holiday, while at worst they came to share in the defiance of those convicts who chose to die ‘game’. They believed ‘a bond had grown up between the condemned and the mob that the authorities were impotent to sever’.

The authorities had no wish to exacerbate this disorder, whether prompted by disputes over taking bodies for dissection or a more general challenge to the forces of order, by staging more executions. Instead, in an attempt to intimidate the crowd, the Act added a further dimension of terror to the executions of those convicted of the most egregious crimes. In a subsidiary clause, it addressed the problem of the grotesque fights over corpses at the gallows by prescribing transportation for anyone convicted of attempting to rescue the bodies of those sentenced to dissection or hanging in chains. The Act also constituted a direct challenge to the culture of defiance among convicts and their supporters. By requiring that condemned murderers be kept in solitary confinement during the much shortened interval between their sentence and their execution, the Act constrained the prison visits that contributed to the celebrity culture of crime and made the job of the criminal biographers more difficult.

Nonetheless, these provisions applied only to those convicted of murder. Prison visiting did not end, and criminal biographies continued to be published. While the Murder Act is generally believed to have reduced disorder at Tyburn, a strong potential for conflict remained when non-murderers were executed, and some riots still occurred. When five convicts were executed on 12 May 1755, for example, ‘the Surgeons had got Possession of two of the Bodies, but the Mob soon deprived them of their Prize, and buried them in the Fields’. To the extent that disorder did decrease after 1752, much of the explanation lies with the sharp fall in the number of executions between 1752 and the early 1760s, rather than in any change in the behaviour of surgeons and the crowd.

Rewards, thief-takers and the Bow Street Runners

The net result of the legislation passed in consequence of the post-war panic about crime was limited. The few Acts that made it onto the statute books were more significant for their aspirations to discipline plebeian London than for their impact in suppressing crime and vice or controlling the crowd. Several contemporary proposals which would have wrought substantial changes to policing were not adopted, including Henry Fielding’s 1749 draft bill, while the proposals that emerged from the Felonies Committee giving justices of the peace greater oversight over the parish watch and poor relief, designed ‘to induce Parishes to do their Duty’, were quietly shelved. The parishes won this battle for control of the watch and the workhouses, and the only legislation on policing passed took the form of additional watch acts, extending the system already in force in Westminster and the west end to the eastern and northern suburbs. Instead, the most significant development in policing in these years was the initiative of Henry Fielding, reacting to the threats posed by highwaymen (particularly when in gangs) and the corrupt thief-takers who were supposed to apprehend them, to create the Bow Street Runners.

Despite the executions of several members of the Black Boy Alley gang in 1744, groups of criminals continued to act in concert, elites continued to construe these groups into ever more threatening ‘gangs’ and the authorities were forced to respond. In the introduction to his Enquiry, Fielding claimed:

there is at this Time a great Gang of Rogues, whose Number falls little short of a Hundred, who are incorporated in one Body, have officers and a Treasury; and have reduced Theft and Robbery into a regular System.

Fielding was referring to the ‘Royal Family’ – a large group centred around members of a privateering squadron which included former participants in the Black Boy Alley gang. The Royal Family became notorious in January 1749 when they staged an armed attack on the Gatehouse Prison to rescue Thomas Jones alias Harper. Jones had been arrested for pickpocketing, and at least ten members of the gang were involved in the rescue. The Royal Family may not have been as large and coherent as Fielding claimed, but it was nonetheless formidable, and they were willing to publicly challenge judicial authority. One witness described how following the attack, ‘they made a terrible huzzaing; after they had got him out, I heard them say they would come back and pull down the goal [sic]’ . This was not the only gang active at this time: another, less well known (and unnamed), group was centred around Henry Webb and Benjamin Mason, alias Ben the Coalheaver. This group contained at least thirteen men, who ‘committed a great Number of Robberies together’.

The government’s response was the tried and failed one of offering rewards for the apprehension of the most notorious criminals. In February 1749 the £100 reward for the conviction of street robbers and highwaymen in London was reinstated (this remained available until early 1752), and in January 1750 a special £100 reward was offered for the capture of Thomas Jones. Other rewards were offered by parishes and individual victims. Measured by the amount of money paid out, these rewards were a huge success: in 1750–2 the government proclamations cost the Treasury £11,100, indicating at least eighty successful prosecutions for robbery. Many of the thief-takers who had been active in the 1740s were thereby enabled to continue or resume their activities, including William Palmer Hind, Charles Remington, John Berry and Stephen McDaniel, and many new ones became active. Ruth Paley lists twelve ‘leading thief-takers’ and twenty-two ‘less active ones’ working in this period. As always, thief-takers relied not only on supportive local justices of the peace but also on their connections with criminals for information. Many had criminal records themselves: Edward Mullins had been a member of the Royal Family.

Instead of preventing crime, the rewards encouraged it, as a result of thief-takers subverting their purpose. Taking advantage of the moral panic, it became easy for thief-takers to secure convictions, as their ‘evidence was received with extraordinary credulity’ in the courts. Consequently, thief-making gangs once again flourished, staging crimes and initiating false prosecutions in order to profit from the rewards. Through extensive use of perjury, extortion and blackmail, as well as violence, in Ruth Paley’s assessment they turned ‘the legal system into what was, in effect, a sophisticated offensive weapon’, for profit as well as in order to persecute their enemies. This amounted to ‘a systematic manipulation of the administration of the criminal law for personal gain’. In the end, the thief-takers were as much of a threat to law and order as the robbers they were meant to apprehend.

It was in response to both the apparently unprecedented law-breaking of highwaymen and gangs and the corruption of the thief-takers that Henry Fielding introduced the Bow Street Runners. In 1749–50 he organised a group of men, comprising constables, ex-constables, prison officers and thief-takers, whom he could send out on a regular basis to apprehend serious offenders for examination at Bow Street. While he paid these men a retainer (and thus maintained some control over them), they also kept any statutory rewards they were entitled to claim. According to many historians, these officers (they would not actually be called ‘Bow Street Runners’ for many years) mark the origins of the world’s first modern police detective force. Indeed, Fielding made strenuous attempts to emphasise the novel character of his runners, and to differentiate them from the frequently corrupt thief-takers who came before. However, this proved impossible. Joshua Brogden, Fielding’s clerk, had long-standing connections with thief-takers, and some of the men Fielding recruited in the early years were thief-takers themselves. There is even some evidence that Stephen McDaniel and John Berry were among Fielding’s recruits. These two men had already been involved in a thief-making scandal in 1747 and would be even more sensationally caught out in another one in 1754. Fielding soon replaced the most corrupt and criminal of these men and claimed that his officers were restricted either to constables or ex-constables, but nonetheless he felt the need to keep their names secret. Moreover, seeking to have it both ways, he justified the work of thief-takers in his Enquiry.

In spite of their tainted origins, by creating this new body of organised detectives Henry Fielding and his half-brother John, who took over the Bow Street office in January 1754, had radical ambitions to change how London was policed. Henry advocated withdrawing government rewards, and in 1752 convinced the Privy Council to stop offering extraordinary rewards by royal proclamation. Instead, he argued for his force to be at least partly funded from central resources, and from 1753 obtained £200 per annum from the government, increased to £400 in 1757. While the runners continued to rely on rewards offered by victims, this funding change altered the character of the relationship between criminals and the police charged with their capture.

Perhaps more importantly, victims of crime and the public were encouraged to rely on these officers to apprehend serious offenders, rather than attempt to capture them themselves. In newspaper advertisements from as early as 1749, the public were asked to send descriptions of thieves and stolen goods to Bow Street so they could be advertised, and from 1754 they were effectively requested to hand over responsibility for apprehending the culprits to the runners. This change was in part a response to the growing temerity of the public in seeking out and arresting criminals – something commentators including John Fielding frequently derided. However, it also represents an attempt to gain greater direct judicial control over the processes of detecting and arresting suspects in order to prevent extra-legal negotiations between criminals and those who apprehended them. The Bow Street Runners were also given wider policing responsibilities. In particular high-risk areas or where local inhabitants demanded it, such as in Westminster squares and on highways leading into the city, the officers conducted patrols both on foot and on horseback. As is clear from the accounts submitted by John Fielding to the Treasury, they also spent a substantial amount of time regulating and suppressing forms of popular recreation which were thought to lead to crime. As he explained in his Account of the Origin and Effects of a Police Set on Foot by His Grace the Duke of Newcastle in the Year 1753,

In large and populous Cities, especially in the Metropolis of a flourishing Kingdom, Artificers, Servants and Labourers, compose the Bulk of the People, and keeping them in good Order is the Object of the Police, the Care of the Legislature, and the Duty of the Magistrates, and all other Peace Officers.

In sum, through their prominent role in apprehending criminal suspects throughout the metropolis as well as in regulating popular entertainments, the Runners, in the words of John Beattie, ‘changed the face of official policing in London’. But since links with thief-taking were impossible to eliminate, the runners remained tainted by accusations of corruption (this was not helped by the fact that John Fielding continued to call them ‘thief-takers’). Hostility was also prompted by their methods. Like thief-takers, the Bow Street officers relied on paid informers who passed on gossip and rumours picked up in alehouses and taverns, and, in a new departure, they used the records kept by Fielding at Bow Street ‘about people suspected of committing offences and of those who had been charged but escaped conviction and punishment’. In some cases, ‘the runners went after men and women on their lists of “known offenders” who seemed to fit the descriptions given by the victims’. In the process, Fielding and the runners formalised the time-honoured police practice of ‘rounding up the usual suspects’. Focusing on the ‘usual suspects’, however, provoked hostility leading in turn to a need for anonymity for the Runners. As Fielding recognised, ‘as the thief-takers are extremely obnoxious to the common people, perhaps it might not be altogether politic to point them out to the mob’.

Despite popular hostility, the Fieldings claimed their new methods were a success. They planted numerous reports in the newspapers of robbers apprehended and gangs broken up by their men. In December 1753 Henry claimed that in the few weeks since the Duke of Newcastle had begun to fund the runners: ‘not one Robbery, or Cruelty hath been heard of in the Streets, except the Robbery of one Woman, the Person accused of which was immediately taken’. This was a disingenuous exaggeration since there are four trials in the Old Bailey Proceedings alone for violent thefts committed between 10 November and 4 December. And while 1754 did see a decline in prosecutions for violent theft, there were still twenty-seven offences prosecuted at the Old Bailey. Neither individual nor gang crime could be crushed so easily. Despite the onset of the Seven Years War in 1757, which was expected to lead to a reduction in crime, John Fielding reported that new gangs had begun to operate. Under the guise of the ‘Family Men’ or the ‘Coventry Gang’, members of the Royal Family continued to commit crimes into the 1760s.

There was also the continuing problem of thief-making. While the Bow Street officers appear to have pushed corrupt thief-takers out of Westminster, they continued to flourish in other parts of the metropolis throughout the 1750s, and, as Paley argues, ‘not only [Henry] Fielding but also the whole of the contemporary legal establishment must have been well aware of what was going on’. The most notorious scandal involved the thief-taker Stephen McDaniel, who had apparently acted as a Runner and participated in arresting a member of the Royal Family before he was dismissed from Bow Street by Fielding in 1751. McDaniel continued to act as a thief-taker and his ‘gang’ engaged in numerous thief-making conspiracies throughout the early 1750s, though they seem to have avoided bringing cases to the Old Bailey (prosecuting cases outside London instead). In August 1754 they were exposed at the Kent Assizes by Joseph Cox, high constable, who arrested McDaniel, John Berry, James Salmon and James Eagan and charged them with conspiracy to initiate a false prosecution against Peter Kelly and John Ellis for robbery in order to profit from the parliamentary reward. In February 1756 all four were tried and convicted of this conspiracy at the Old Bailey. Cox also exposed several of the gang’s other conspiracies. In June, McDaniel, Berry and Mary Jones were tried and convicted for the murder of Joshua Kidden , whom they had falsely charged and convicted of robbing Jones in February 1754. Kidden had ‘declar’d his innocence to the last’, and his friends and even the Ordinary of Newgate were entirely convinced. Regardless, he was hanged on Monday 4 February 1754, while the crowd threw snowballs and behaved as if they ’had been rather at a bear-baiting, than a solemn execution of the laws’.

Although sentenced to death, the punishments of McDaniel, Berry and Jones were never carried out, owing either to concerns about the legal validity of the offence of ‘murder by perjury’ or to a desire on the part of the legal establishment not to put these thief-takers in a position where they might expose damaging information about official collusion in their activities. They were sentenced to the pillory instead, and the fact that McDaniel and Berry were heavily protected by the keeper of Newgate and one of the sheriffs, shielding them from understandable popular outrage at their crimes, suggests that the officials were worried. As Ruth Paley argues, ‘the reason the thief-takers were tolerated for so long was that to make any move against them was to risk exposing the corruption of the whole system of the administration of the criminal law in the metropolis’.

Thief-taking (and no-doubt thief-making) continued, but defendants acquired a useful card to play in their defence. The ill-disguised link between the Runners and thief-taking provided defendants with a tactic to use in court, where they could attempt to discredit the Runners by accusing them of acting like thief-takers. When one of the most active early Runners, William Pentlow, testified against Thomas Lewis and Thomas May in a highway robbery case in 1750, ‘The two prisoners, especially May, much abused this headborough, as a person that would swear away any person’s life for a trifle.’ Henry Fielding was forced to rise to Pentlow’s defence, saying ‘he sincerely believed there was not an honester, or a braver man than he in the king’s dominion’, and the two defendants were convicted. Others were more successful. When William Page, a notorious highwayman zealously pursued by John Fielding, was finally tried at the Old Bailey in February 1758, he attacked the principal prosecution witness, his alleged accomplice William Darwell, suggesting that his association with Fielding undermined the validity of his testimony:

I know nothing of him, and why he should place this matter to my account, I don’t know. He has had access to my lodgings, and has had a long connection with Mr. Fielding from his own testimony. He is every thing that is bad and infamous, in declaring himself a highwayman. He would have given testimony against any person that he should happen to fix upon, to save his own life. He glories in his wickedness.

Page was acquitted. When the highwayman Paul Lewis was tried for robbing Mary Brook in 1762, he also conducted his own defence, carrying out robust cross-examinations of the prosecution witnesses. In doing so, he suggested that the prosecuting attorney had framed him and that the constable was a ‘hired constable’ and a ‘thief-catcher’ (he, too, was acquitted). These arguments were also used by defence counsel.

In response to the success of defence strategies like these, the Fieldings introduced a further innovation – more elaborate pre-trial hearings. Traditionally, the function of a preliminary hearing was limited, since justices were required to commit all accused felons to prison and forward the accusations against them for consideration by the grand jury. However, the Fieldings began to use their Bow Street office not simply to determine which of the accused to commit and take the necessary depositions but also to assess the evidence against suspects and solicit additional evidence where it was thought to be necessary to strengthen weak cases. As reports in his Covent Garden Journal suggest, Henry pioneered the practice of examining witnesses separately and waiting for the contradictions to emerge. While to modern eyes this seems like a natural detective practice, it was actually in contradiction of traditions of open justice in which all those involved in a dispute spoke to the same audience. Just as the introduction of counsel into criminal trials from the 1730s and 1740s had made the proceedings more ‘adversarial’, Fielding’s innovations meant that pre-trial hearings began to acquire the character of an increasingly unequal interrogation.

In cases where the evidence was judged to be weak, suspects were held while new victims and witnesses were located through advertisements in the press, inviting anyone with potentially useful information (or a grudge) to come and view the prisoner, and participate in a ‘re-examination’. Although this system was perfected by John Fielding, it was probably initiated by Henry, based on a provision of the 1752 Disorderly Houses Act which allowed justices to hold persons accused of theft for up to six days without charging them. Cases for the prosecution were thus potentially much stronger by the time they were forwarded to the Old Bailey, where cases originating at Bow Street became increasingly common. In John’s first decade in office (1756–66), ‘more than a third of the accused felons sent for trial at the Old Bailey from Middlesex were committed as a result of proceedings at Bow Street, the vast majority conducted by Fielding himself’. The pre-trial publicity Fielding generated by reporting these hearings in the newspapers provoked criticism in the 1770s, but from their beginning those subjected to the Fieldings’ new methods of arrest and pre-trial hearings fought back. When the burglar William Tidd was examined by Henry Fielding, he ‘d – d the justice, and said he was as big a thief as himself’. Innovations at Bow Street evolved in a continuing dialectic with the challenges posed by the thief-takers, thief-makers and the accused thieves of plebeian London.

‘The dogs of reformation’

Virtually the entire response to the post-war anxiety about crime can be seen as a renewed attempt at a reformation of manners, picking up where the previous campaign left off when it collapsed in 1738. Understandings of the causes of crime remained firmly traditional, blaming irreligion, immorality and idleness. The 1750s approach to the reformation of manners, however, was different in two respects. First, this new campaign more clearly differentiated the vices of the poor from the forgivable failings of the well-to-do. Henry Fielding’s social policy prescriptions explicitly focused on the poor and their supposed propensity for ‘luxury’. While he occasionally criticised the vices of the rich in the Covent Garden Journal and set himself up as ‘censor of the nation’s morals’, he did not think the wealthy needed judicial discipline. Similarly, his half-brother John opined in 1763 that while all brothels were to be condemned, the ones that needed to be closed most urgently were the ‘low, and common bawdy-houses, where vice is rendered cheap, and consequently within the reach of the common people’. The second distinctive feature was the limited involvement of magistrates. Despite resolutions passed by justices of the peace in the early years of the post-war crisis and the passage of the Gin and Disorderly Houses Acts in 1751–2, there were few extra prosecutions in the early 1750s. Magistrates were actively concerned about the opposition a new campaign would create. No doubt aware of the difficulties encountered during previous attempts to close down disorderly houses, particularly during the late 1720s, they treaded cautiously.

The only exceptions were the Fieldings, who, motivated by their ambitious redefinition of policing, defied the trend. In the early 1750s, Henry was involved in a campaign against gaming houses, and from 1755 John waged a battle against forms of popular culture which he believed encouraged vice. The annual accounts of expenditure he submitted to the Treasury between 1755 and 1758 include sums for suppressing several types of plebeian recreation, including ‘cock-scaling on Shrove Tuesday’ and ‘an illegal meeting of servants and apprentices at a dance at the Golden Lyon near Grosvenor Square’. He devoted even more effort to prosecuting vice following the onset of war in 1757. He drafted a successful bill which prohibited gaming by journeymen, labourers and servants in public houses, and pursued a vigorous campaign against gaming houses. While he attempted to avoid formal prosecutions, relying instead on warnings and threats to withdraw licences, his tactics, including paying large fees to secret informers (in one case he even paid for a ‘disguise’) and burning gaming tables in public, were deeply unpopular. As he himself recognised, he had become ‘obnoxious to many Bodies of People’. This may explain rumours spread in the summer of 1758 that he had been suspended from the bench and committed to Newgate prison.