Parliamentary Reform

Jonas Hanway, by James Northcote, c.1785. NPG 4301. © National Portrait Gallery.

Jonas Hanway, by James Northcote, c.1785. NPG 4301. © National Portrait Gallery.

Introduction

Following two decades of dramatic expansion in the role of Associational Charities, and most particularly the Foundling Hospital, the focus of change shifted to Parliament after 1760. In part this was a reaction to the end of the period of the General Reception at the Foundling Hospital, during which a government grant had funded the admission of all comers. The grant had allowed a dramatic expansion of the Hospital's activities which in turn sustained the interest and consumed the efforts of many London-based reformers. The General Reception saw the admission of over 15,000 children, accompanied by a sharp spike in child mortality rates. The end of the parliamentary grant supporting these activities came in 1760, and caused the Hospital to sharply curtail its activities. Jonas Hanway in particular, but also hospital governors and parliamentarians such as Rose Fuller, turned their attention elsewhere.1 As well as responding to the increasingly complex system of charity and parochial relief, this new focus on parliamentary reform was also part of a larger transition in the debate surrounding the workings of the poor law and local government.

Although there had been numerous attempts to reconstitute the poor law prior to 1760 (the proposals of the Board of Trade in the 1690s and William Hay's failed bill of 1736 form the most obvious examples), no reforms that aspired to more than a permissive, local and piecemeal innovation, were successful.2 This did not change after 1760 - no comprehensive reform package relating to poor relief was passed by Parliament at any point during the eighteenth century - but a rising tide of criticism sprang from all sides, and a series of innovative and effective acts (if nonetheless local and permissive) were passed. With the exception of Gilbert's Act, this piecemeal late-eighteenth century legislation was driven by concern specifically about the poor of London and the workings of the system in the capital.3

An Annual Register of all Parish Poor Infants (1762)

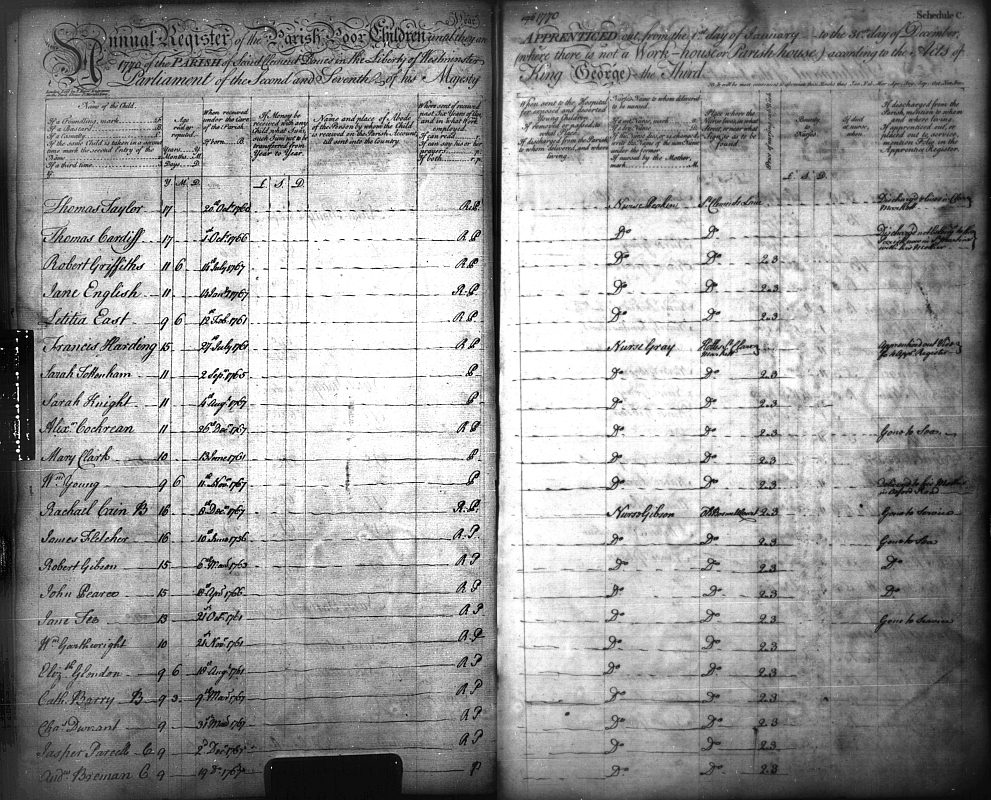

Jonas Hanway was intimately involved in the management of the Foundling Hospital throughout the 1750s, and with the end of the General Reception in 1760 sought ways to extend his contribution to preserving the lives of poor and parish children. In the first instance he hoped that all parish children could be boarded with country nurses managed by the Foundling Hospital, but finding little support for this suggestion, he turned his efforts to an extensive survey of the life expectancy of children raised by the parishes of London. The figures he generated were shocking, and were intended to shock, and their accuracy is uncertain. In the combined parishes of St Andrew Holborn above the Bars and St George the Martyr, he recorded 284 children as having been received by the parish between 1749 and 1756, of whom 222 (71%) died in childhood. In St Martin in the Fields the equivalent figures were 312 children and 158 deaths (51%).4 Armed with statistics which at their most horrific suggested a child mortality rate approaching 100% in some parishes, Hanway began promoting the passage of an Act of Parliament which would require London parishes to maintain a comprehensive Register of Poor Children received by the parish under the age of four years, and to report the contents of these registers to the both the local vestry and the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks annually.

Through the good offices of Rose Fuller, who as well as being a Member of Parliament was an active governor of the Foundling Hospital, the Act passed in the Spring of 1762, and came into force the following year.5 It included detailed schedules describing two different sorts of registers, one for parishes with workhouses, and another for parishes without. Pre-printed forms were quickly created, and many of these Registers of Poor Infants (RI) and Registers of Poor Children (RC) survive in parochial archives.6

St Clement Danes, Annual register of parish poor children, 1767-1786, Westminster Archives Centre, Ms B1257, LL ref: WCCDRC365000037 & 38.

St Clement Danes, Annual register of parish poor children, 1767-1786, Westminster Archives Centre, Ms B1257, LL ref: WCCDRC365000037 & 38.

In some respects Hanway's decision to promote an Act that had at its core an apparently simple request for information reflects his experience of the Associational Charities. These were dependent on the ability of their promoters to make a compelling, humanitarian case for whichever object of charity they hoped to relieve. Hanway was using the collection and publication of information about social problems as a device to generate social concern in precisely the same way the Associational Charities had been doing for decades, but was applying the methodology to parish governance for the first time.

In the years that followed the passage of Hanway's first Act compliance was patchy, but sufficient returns were reported to the Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks to allow Hanway to begin to build a larger case directed at both ensuring parish children were boarded in the countryside, and that parishes were held to account in relation to the apprenticeship of the children left in their charge.

Better Regulation of the Parish Poor Children (1767)

In an ever more extensive series of newspaper articles and extended pamphlets Hanway began to build a case for further reform. In 1766 he published An Earnest Appeal for Mercy to the Children of the Poor, which incorporated the statistics generated for 1765 in response to the earlier Act of Parliament. These statistics suggested that in several parishes, including St Olave and Christ Church, Southwark, and St Mary le Strand, fully 100 per cent of children born or received into the parish workhouse in the preceding year, were dead by their first birthday; and that even in large Westminster parishes such as St Clement Danes (which at this time relied on independent nurses rather than a workhouse), the equivalent figure was 90 per cent (seventeen out of nineteen children received had died).7

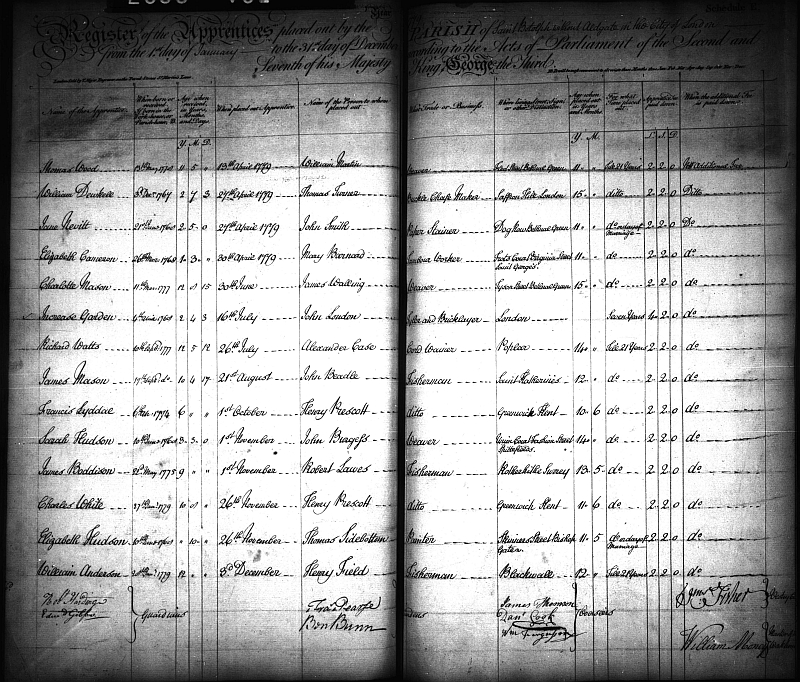

The resulting Act of 1767 extended the requirement for parishes to maintain and report clear records to include a further Register of Apprentices (RA), laid out according to a series of new schedules detailing the information to be included. More significantly, the Act also required that all children below the age of four years should be nursed in the country at least three miles from London and Westminster (five miles in certain circumstances). The length of time a London parish child could be apprenticed was also lowered to a maximum of seven years, or until the age of twenty-one for both boys and girls. The Act also stipulated that the minimum fee be given with a parish apprentice should be £4 2s, and that this fee should be paid in two instalments - the second half three years into the apprenticeship. Finally, the Act established a series of Guardians of the Poor drawn either from the nobility or the highest ranking members of the parish community, to oversee and inspect the workings of the poor relief system. To Hanway's disappointment, the ninety-seven parishes within the City of London were excluded from the provisions of the Act, as were four further urban parishes from Middlesex and Surrey.8

"St Botolph Aldgate, Register of apprentices, 1777-1805, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms 2658, LL ref: GLBARA107010009 & 10."

"St Botolph Aldgate, Register of apprentices, 1777-1805, London Metropolitan Archives, Ms 2658, LL ref: GLBARA107010009 & 10."

Between them, Hanway's two Acts drew significant attention to the issue of infant mortality in the parishes of London, and led to substantial improvements in the conditions experienced by parish children. The registers themselves provide good evidence of this. In the ten years following its passage (1768-1778), 9,727 children under the age of six were recorded as being given up to parochial care in fifteen large urban parishes, of whom only 2,042, or 21 per cent, were dead at the end of the period.9 The provisions for apprenticeship also substantially improved the position of parish children, and were extended national a few years later.

In many respects, Hanway's Acts set the tone for Parliamentary enquiries in subsequent decades. The emphasis on clear and well laid out statistics can be seen in the extensive Parliamentary reports published in 1776 and 1786, which were in turn followed by a series of exhaustive enquiries by both private individuals such as Frederick Morton Eden in the 1790s, and several long-standing Parliamentary commissions in the first decades of the nineteenth century.10

At the same time, the provisions for the nursing of parish children in the countryside encouraged the evolution of Baby Farms and Contract Workhouses on the outskirts of London, where conditions could be as brutal as those found in any urban workhouse. The specific provisions for apprentices also helped to regularise the legal position for parish apprentices, and substantially aided the evolution of a system of mass factory apprenticeships, whereby over the ensuing decades parish children from London were shipped to the new spinning and weaving factories of Yorkshire and Lancashire in their hundreds and thousands.11

Better Relief and Employment of the Poor (1782)

If Hanway's Acts drew from the experience of poverty in London and his work with Associational Charities, the Act of Parliament associated with Thomas Gilbert was in the older tradition of the Corporations of the Poor and of William Hay's Bill of 1736, in that it sought to incorporate parishes into larger units, in order both to ensure a more professional administration and to obviate the worst characteristics of the system of settlement and removal. In the 1760s and 1770s a number of East Anglian parishes had come together under the authority of local acts of parliament to establish large collective workhouses, or hundred houses (a "hundred" was a sub-division of a county and could include anywhere up to a dozen or more parishes). This kind of legal association was then taken up and regularised in Gilbert's Act, which authorised the creation of Gilbert Unions. The Act was passed in 1782.12

Beyond creating a permissive authority to combine parishes into a union for the purpose of building a large shared workhouse, the Act also restricted workhouse provision to the young, the old and the disabled, excluding the able bodied, who were to be found employment near their own homes. The Act also established a system of Boards of Guardians, drawn from the constituent parishes and the local gentry, and validated by Justices of the Peace.

Robert Barker. Panorama of London. 1792. British Museum, British Masters Portfolio. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Robert Barker. Panorama of London. 1792. British Museum, British Masters Portfolio. © Trustees of the British Museum.

No Gilbert Unions were established in London, but its provisions formed an important background to the evolution of poor law debate leading up to the New Poor Law of 1834.13

Towards the Early Nineteenth Century

During the later 1780s and 1790s essentially metropolitan concerns about the well being of children continued to take up parliamentary time. David Burton, with the energetic support of Jonas Hanway and the master sweep, David Porter, secured the passage of an Act for the Better Regulation of Chimney Sweepers and their Apprentices (1788).14 This legislation regulated the apprenticeship of children to the trade, and although chimney sweeps and the horrific conditions they suffered could be found throughout the country, the problem was perceived to be a metropolitan one. This campaign, in turn, fed into the programme of publication and enquiry, militancy and campaigning that culminated in the first Factory Act, or The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act of 1802, which itself, while regulating primarily northern factories, was directed at improving the conditions suffered by the large number of London parish apprentices sent north.15

This stream of London-centred changes and acts was paralleled by a series of in some ways contradictory developments driven by concern with essentially rural poverty and relief, and focussed on the counties of south-east England. The 1790s, in particular, witnessed a crisis in rural poor relief driven by harvest failure and war. These crises in turn drove the rapid evolution of new, or newly popular, forms of pauper labour and out relief, including the Speenhamland system.16

What was created in these decades were two distinct strands of thought in relation to poor relief and institutional care. On the one hand, the London based (and more broadly urban) tradition of large general parochial workhouses providing extensive medical care, of associational charities for specific types of poverty, and of the careful, legally defined oversight and regulation of local government and employment conditions, forms a distinct, complex and remarkably generous response to the challenges of social welfare. At the same time, the Speenhamland system and associated rural developments reflect a greater concern to manage labour and class relations at the expense of the poor. Both these strands of thought contribute to the reformulation of the system in 1834 and creation of the New Poor Law.

Introductory Reading

- Honeyman, Katrina. Child Workers in England, 1780-1820: Parish Apprentices and the Making of the Early Industrial Labour Force. Aldershot, 2007.

- Innes, Joanna. Managing the Metropolis: London's Social Problems and their Control, c.1660-1830. In Clark, Peter and Gillespie, Raymond, eds, Two Capitals: London and Dublin 1500-1840. Proceedings of the British Academy, 107, 2001, pp. 53-79.

- Innes, Joanna. Origins of the Factory Acts: The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act, 1802. In Landau, Norma, ed., Law, Crime and English Society, 1660-1830. Cambridge, 2002, pp. 230-255.

- Innes, Joanna. Parliament and the Shaping of Eighteenth-Century English Social Policy. Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, 5th ser., 40 (1990), pp. 63-92.

- Taylor, James Stephen. Jonas Hanway, Founder of the Marine Society: Charity and Policy in Eighteenth-Century Britain. 1985.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 The best account of these developments is James Stephen Taylor, Jonas Hanway, Founder of the Marine Society: Charity and Policy in Eighteenth-Century Britain (1985). ⇑

2 See Paul Slack, From Reformation to Improvement: Public Welfare in Early Modern England (Oxford, 1999), ch. 6. ⇑

3 See Joanna Innes, Managing the Metropolis: London's Social Problems and their Control, c.1660-1830, in Peter Clark and Raymond Gillespie, eds, Two Capitals: London and Dublin 1500-1840 (Proceedings of the British Academy, 107, 2001), pp. 53-79. ⇑

4 Jonas Hanway, Letters on the Importance of the Rising Generation (1768), vol. 2, pp. 80-1. ⇑

5 An Act for the Keeping Regular, Uniform and Annual Registers of all Parish Poor Infants Under a Certain Age, Within the Bills of Mortality (1762), 2 George III c. 22. ⇑

6 Taylor, Jonas Hanway, p. 106. ⇑

7 Jonas Hanway, An Earnest Appeal for Mercy to the Children of the Poor (1766). ⇑

8 An Act for the Better Regulation of the Parish Poor Children (1767), 7 George III c. 39. ⇑

9 M. Dorothy George, London Life in the Eighteenth Century (1925, 1965), p. 405. ⇑

10 For a discussion of these returns as they relate to London in particular, see David Green, Pauper Capital: London and the Poor Law, 1790-1860 (Aldershot, 2010), chs. 1 and 2. ⇑

11 Katrina Honeyman, Child Workers in England, 1780-1820: Parish Apprentices and the Making of the Early Industrial Labour Force (Aldershot, 2007). ⇑

12 22 George III c. 83. See The Workhouse website for the full text of the act. ⇑

13 Green, Pauper Capital, ch. 2 ⇑

14 28 George III c.48. ⇑

15 42 George III c. 73. See Joanna Innes, Origins of the Factory Acts: The Health and Morals of Apprentices Act, 1802, in Norma Landau, ed., Law, Crime and English Society, 1660-1830 (Cambridge, 2002), pp. 230-55. ⇑

16 See Steve King, Poverty and Welfare in England 1700-1850 (Manchester, 2000), ch. 6. ⇑