St Dionis Backchurch

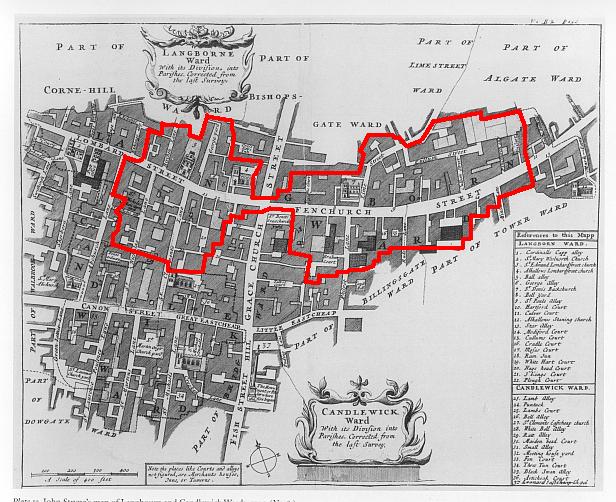

St Dionis Backchurch; John Strype, John Stow's Survey of London and Westminster, 1720. © Motco Enterprises Ltd, 2003 (base map only).

St Dionis Backchurch; John Strype, John Stow's Survey of London and Westminster, 1720. © Motco Enterprises Ltd, 2003 (base map only).

Introduction

Located in the heart of the City of London, St Dionis Backchurch was a typical small, rich City parish. With a population of under 1,000 throughout the eighteenth century, few pockets of serious deprivation and a substantial portfolio of charitable funds, the parish could afford to be generous to its pensioners and to reward its officers with regular parish dinners. In some ways, the management of St Dionis Backchurch harkens back to an older sixteenth and seventeenth-century tradition of parochial administration, but its remarkably voluminous and detailed records, the vast majority of which have been reproduced on this site, reflect careful management and administrative probity.

Location

The parish of St Dionis Backchurch is located in Langbourne Ward in the City of London, directly north of London Bridge. The parish snakes along Fenchurch Street and Lombard Street and is bisected by Grace Church Street and the southern end of Bishopsgate Street. The parish also incorporates parts of Lime Street, Rood Lane, Philpot Lane, Clements Lane, and Birchin Lane. It encompasses 4.8 acres of land.

Local Government

As a parish within the walls, St Dionis ceded many administrative functions to the ward in which it was located. This was Langbourne (or Langborn, Langbourn) Ward; although five houses belonging to the parish (out of approximately 140) were located in Lime Street Ward 1. John Strype records that:

The parish itself encompassed two ward precincts which coincided with sub-divisions of Langbourne Ward (north and south). Each precinct had a separate, parish-appointed, churchwarden. The parish was run by an open vestry, whose main activities included church maintenance, the provision of a fire engine, and poor relief.

George Shepherd, View of St Dionis Backhcurch, 1811. British Museum, Crace XXIII.30. © British Museum.

George Shepherd, View of St Dionis Backhcurch, 1811. British Museum, Crace XXIII.30. © British Museum.

In terms of religious administration, St Dionis was an ecclesiastical peculiar and lay in the Deanery of the Arches. Many of the church’s monuments were transferred to All Hallows, Twickenham when the structure designed by Christopher Wren was demolished in the 1880s.3

St Dionis is administratively unusual for its mid eighteenth century tradition of employing female sextons, such as Sarah Parker; its uncommon practice of allowing elderly parishioners to invest in parish annuities – providing a guaranteed income for several widows; and the frequency with which issues of parish policy came to a vote – the precise outcome of which was recorded in the vestry minutes.

Population

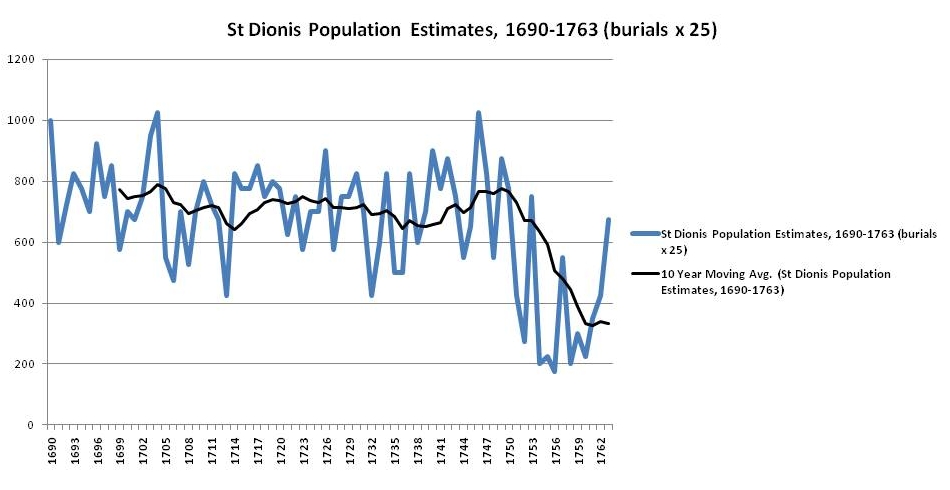

As befits a parish in the fully built-up area of London, its population remained largely stable from the late seventeenth to the early nineteenth centuries.

Jeremy Boulton puts the population at around 800 in the mid seventeenth century, based on an average of 32.5 burials per year between 1657 and 1660 (assuming a burial rate of 40 per 1000).4 Using the Bills of Mortality, it is possible to extend Boulton’s evidence through the mid 1760s. We can also compare this longitudinal estimate with the results of the 1695 Marriage Duty Assessment. According to the Marriage Duty Act returns, St Dionis had a population of 948 in 1695, occupying 148 houses, roughly confirming the population figures derived from the Bills of Mortality, which give an average parish population of 822 for the whole period from 1690 to 1750.5 If the figures for 1750 to 1763 are included, this average drops to 726. But the Bills become markedly less reliable from mid century.6

Prior to 1750 the Bills suggests that following extreme disruption caused by the plague and fire of London, the population of the parish returned to a peak of just over 900 in the mid 1680s, before declining to an average for the first half of the eighteenth century of just over 800.

Evidence from the early nineteenth century censuses suggests that the population remained largely stable in the second half of the century as well. In 1801, the first census records a population figure of 868 for the parish; in 1811, 755; in 1821, 791, and in 1831, 810 persons.

Distribution of Wealth

Ironmongers' Hall in Fenchurch Street, c.1750. T. Loveday. London Metropolitan Archives, q6013417. © City of London.

Ironmongers' Hall in Fenchurch Street, c.1750. T. Loveday. London Metropolitan Archives, q6013417. © City of London.

In the latter decades of the seventeenth century the parish could be counted among the wealthiest in London, certainly in the City of London. According to Hearth Tax evidence from the 1660s, the average dwelling in the parish contained over six hearths, just below the number recorded in the wealthiest London parishes.8 St Dionis was a part of an area noted as home to a high proportion of wealthy lodgers. Using the 1692 Poll Tax returns, Craig Spence suggests that 15.8 percent of households included occupants of this sort, showing that the parish's wealthy and settled population was accompanied by a high number of more temporary, but not poor, neighbours. 9

The high wealth of the parish is further evident in the 1693-4 Four Shillings in the Pound assessments, which suggest that the mean household rent for Langbourne Ward stood at £40 5s per annum – the third highest average rental in the City. 10

As a final measure of wealth, the number of servants per household and the occupational profile of the ward, and by extension the parish, can be derived from the 1692 Poll Tax returns. There were 1.48 servants per household, inclusive of those households headed by a lodger. 11

Economy

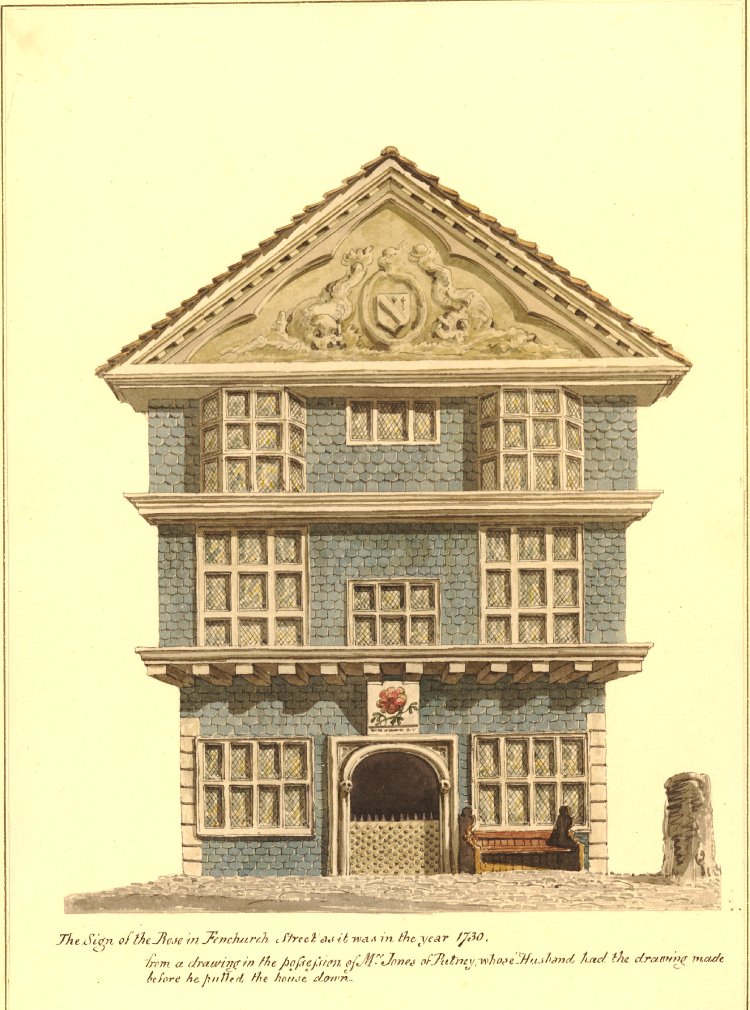

The Rose Tavern, Fenchurch Street, c. 1730. British Museum, Crace XXII.34. © British Museum.

The Rose Tavern, Fenchurch Street, c. 1730. British Museum, Crace XXII.34. © British Museum.

The parish was dominated by overseas merchants and traders. Throughout the eighteenth century it housed the Hudson Bay Company and Pewterers' Hall. Of 641 household occupations recorded in the 1692 Poll Tax returns, the five most common were overseas trade (103), financial services (58), victualling (54), apparel (42) and textiles (41). 12

There was also a range of large inns and ale houses that brought to the parish a varied set of travellers. Many of these acted as coaching and carrying inns, and were conveniently located at the intersection of the routes north to Newmarket and Cambridge, and east towards Colchester. 13 Among the best known were the Rams Head Inn, Ipswich Arms Inn, and the Elephant Inn, which played host to William Hogarth for a number of years. Many of the alehouses were either Elizabethan survivals or else hurriedly built post-fire buildings rushed up to satisfy the requirements of workmen. The best known included the Magpie and Punchbowl, Rose Tavern and King’s Head.

Housing

With the exception of a few streets at the eastern end of the parish, most houses were destroyed by fire in 1666 and rebuilt. But because the freehold for most buildings was owned by the Bridge House Estate, the rebuilding was rapid and largely complete by 1671. The new church was designed by Christopher Wren, and cost £5,737.

In 1721 John Strype described the main streets from west to east as follows:

The parish did, however, contain small pockets of less well built houses and relative poverty, mainly focussed on the older Elizabethan buildings which had survived the fire, located at the eastern end of the parish. Strype suggests that

Poor Relief and Charities

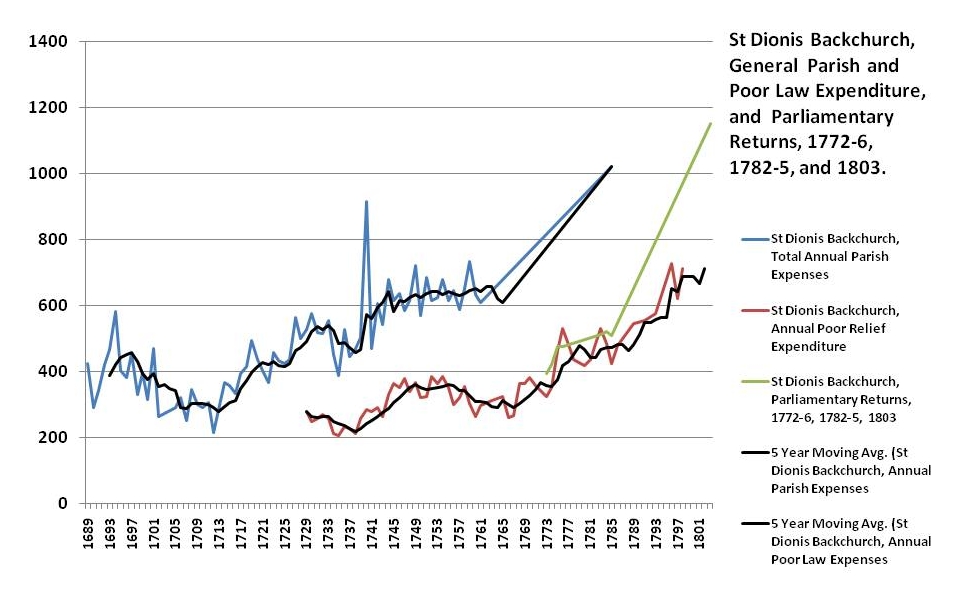

St Dionis had relatively few paupers. In most years between 1762 and 1792 the number of pensioners and the amounts they received are recorded. On average the parish supported seventy-eight individual paupers, with an average cost of £5 8s per year, and a total expenditure on poor relief of between £400 and £600. Some paupers were markedly more expensive than the average. Someone such as Charlotte Dionis - a foundling raised by the parish - had cost over £150 by the time she was eighteen. Catherine Jones, an invalid supported for some twenty-six years after she first appeared on the parish books in 1757, cost approximately £112 in total.

These figures are derived from the Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor Account Books (AC). By 1817, a parliamentary enquiry found that between 1813 and 1815 the parish spent on average £580 per year, though they claimed to be supporting a smaller number of paupers (thirty-six). Despite its stable population, the parish's expenditure on poor relief increased significantly over the century.

General Parish and Poor Relief Expenditure, 1690-1803, in ££s, Derived from Parish Records and Parliamentary Returns.

General Parish and Poor Relief Expenditure, 1690-1803, in ££s, Derived from Parish Records and Parliamentary Returns.

The parish initiated several major policy initiatives. These include the decision to force the poor to wear badges in 1703; and two abortive attempts to establish a parish workhouse in 1725 and 1730. The 1725 initiative is notable for its strategy of attempting to join with other parishes in the ward to establish a joint institution. In 1733, the parish contracted for the care of its poor with John Thruckstone, who ran a workhouse at Tottenham High Cross and also cared for the poor of St Michael Cornhill and St Helen’s Bishopgate. Thruckstone can also be found unsuccessfully applying to care for the poor of St Leonard Shoreditch in 1737, St Clement Danes in 1740, and St Andrew Undershaft in 1742.

The agreement with Thruckstone lasted only two years, and ended as a result of a concerted series of complaints from the poor which are recorded in detail in the Vestry Minutes (MV). In 1734 the parish subcontracted the care of its fully dependent and residential poor to St Mary Newington at 3s a week.

In 1750 there were several attempts (eventually successful) to create a new parish officer of street keeper to arrest vagrants. In 1761 a Nurse Jackson was contracted for care of the poor, but withdrew from the contract, and Richard Birch, the keeper of the Rose Lane workhouse was engaged. This arrangement lasted for six years until 1767, when the parish moved its poor to a house run by Messrs Hughes and Philip at Hoxton. In 1798 the parish once again changed its workhouse contractor and moved its paupers to a house run by a Mr McKensie.

Although the parish had access to, and contracted for, workhouse care throughout most of the eighteenth century, there was no point at which it implemented a thorough workhouse test. The parish also relieved a large number of casual paupers with one-off payments, while other paupers were in receipt of more formal pensions or the collection (i.e. relief funded by collecting money in church on Sunday). The granting of parish annuities for the life of a widow, bought by husbands and implemented on their death, created another type of more wealthy pensioner.

In 1820 the parliamentary returns recorded the parish as having £498 pounds in charitable holdings. Throughout the eighteenth century it distributed approximately £50 per annum to the poor from charitable endowments – the most prominent of which included Lady Harvey’s gift, which allowed £6 per year to poor householders, and a further £6 to be distributed to various parish officers. Other gifts reserved for the poor included Roger Tinndall’s gift, which produced £2 12s per annum, and Alderman Abdy’s gift, worth £7 10s per annum.

Crime and Policing

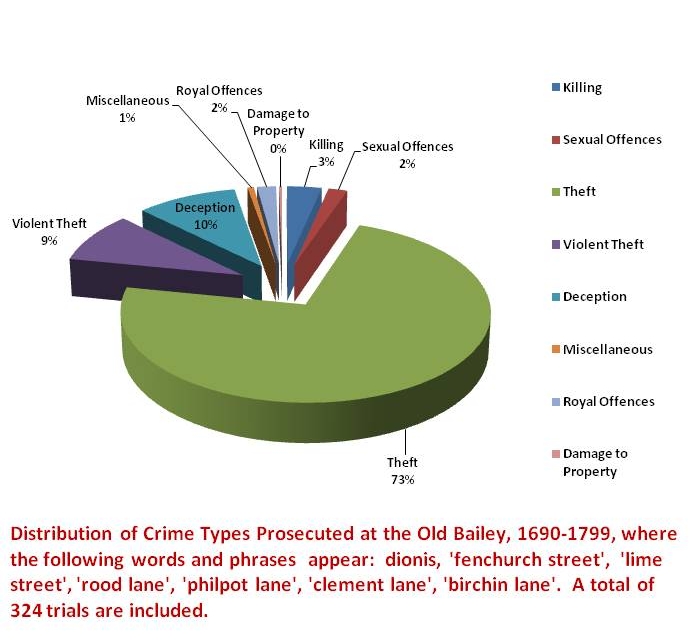

St Dionis Backchurch, Crimes by Type, 1690-1799.

St Dionis Backchurch, Crimes by Type, 1690-1799.

Very few cases of crimes committed in St Dionis Backchurch are recorded as having been prosecuted at the Old Bailey. Only 324 crimes came to trial between 1690 and 1799 where one of the following words or phrases - dionis, fenchurch street, lime street, rood lane, philpot lane, clement lane, birchin lane - reflecting the major streets in the parish was used, and the vast majority were for simple theft (73 per cent). When violent theft is added, theft accounts for 82 per cent of all crimes prosecuted in the parish. This compares to a figure of 89 per cent in these categories for all crimes tried at the Old Bailey during these decades.

The only other significant category of criminal prosecution was for forms of deception. These offences account for almost 10 per cent of the crimes prosecuted, compared to under 3 per cent in this category for all Old Bailey prosecutions. This reflects the large number of merchants and traders resident in the parish.

This relative lack of crime might be attributed to a high level of policing. This was the responsibility of Langbourne Ward, which employed twenty-three night watchmen in 1737. With 530 houses in the ward this works out at one watchman for each 23 houses, well above the City average of a watchman per 32 houses. Similarly, in the 1770s and 1780s the ratio of houses to constables was only 41:1, one of the lowest ratios in the metropolis (the average was 91:1).16

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keywords St Dionis:

Documents Included on this Website

- Bastardy Bonds: Securities for the Maintenance of Bastard Children (WB)

- Books of Clothing Provided by the Parish (BC)

- Churchwardens and Overseers of the Poor Account Books (AC)

- Churchwardens' Vouchers/Receipts from St Dionis Backchurch (PP)

- Letters to Parish Officials Seeking Poor Relief (PR)

- Minute Books of Parish Vestry Sub-Committees (MO)

- Minutes of Parish Vestries (MV)

- Miscellaneous Parish and Bridewell Papers (PM)

- Register of Poor Infants under Four Years in Parish Care (RI)

- Workhouse Inquest (Visitation) Minute Books, St Dionis Backchurch (IW)

Back to Top | Introductory Reading

Introductory Reading

- Boulton, Jeremy. Microhistory in Early Modern London: John Bedford (1601-1667). Continuity and Change 22 (1), 2007, pp. 113-141.

- Power, M. J. The Social Topography of Restoration London. In Beier, A. L. and Finlay, Roger A. P., eds, London 1500-1700: The Making of the Metropolis (1986), pp. 199-223.

- Spence, Craig. London in the 1690s: A Social Atlas. 2000.

Online Sources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.

Footnotes

1 John Smart, London... A Short Account of the Several Wards, Precincts, Parishes, &c. in London [1742], pp. 24, 25. ⇑

2 John Strype, A Survey of the Cities of London and Westminster ... Written at First in ... 1598 by John Stow ... Corrected, Improved and Very Much Enlarged by John Strype (1720). Book 2, p. 164. ⇑

3 Jeremy Boulton, Microhistory in Early Modern London: John Bedford (1601-1667), Continuity and Change 22 (1), 2007, p.134, fn. 24. ⇑

4 Boulton, Microhistory, p.133, fn. 16. ⇑

5 P. E. Jones and A. V. Judges, London Population in the Late Seventeenth Century, Economic History Review, 6 (1935), p. 19, Table III. ⇑

6 M. Dorothy George, London Life in the Eighteenth Century (1925, 1965), p. 398, Table 1 B. ⇑

7 Based on Thomas Birch, A Collection of the Yearly Bills of Mortality, from 1657 to 1758 Inclusive (1759); Worshipful Company of Parish Clerks, A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 12, 1758 to December 11, 1759 (1759); ibid., A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 11, 1759 to December 9, 1760 (1760); ibid., A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 11, 1760 to December 15, 1761 (1761); ibid., A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 15, 1761, to December 14, 1762 (1762); ibid., A General Bill of all the Christenings and Burials from December 14, 1762, to December 13, 1763 (1763). ⇑

8 M. J. Power, The Social Topography of Restoration London, in A. L. Beier and Roger A. P. Finlay, eds, London 1500-1700: The Making of the Metropolis (1986), p. 216, & Table 28. ⇑

9 Craig Spence, London in the 1690s: A Social Atlas, (2000), p. 99 ⇑

10 Spence, London, p. 176 ⇑

11 Spence, London, p. 179. ⇑

12 Spence, London, pp. 180-182. ⇑

13 Spence, London, p. 35 ⇑

14 Strype, Survey ... London and Westminster, Book 2, p. 164 ⇑

15 Strype, Survey of ... London and Westminster, Book 2, p. 164 ⇑

16 John Beattie, Policing and Punishment in London, 1660-1750: Urban Crime and the Limits of Terror (Oxford, 2001), p. 195; Drew D. Gray, Crime, Prosecution and Social Relations: The Summary Courts of the City of London in the Late Eighteenth Century (Basingstoke, 2009), p. 61. ⇑

St Dionis Backchurch Population Derived from the Bills of Mortality, 1690-1763.

St Dionis Backchurch Population Derived from the Bills of Mortality, 1690-1763.