Researching Illness

William Hogarth, A Prostitute Treating Herself for the Pox, c.1731. British Museum, Croft-Murray (unpublished) 10. ©Trustees of the British Museum.

William Hogarth, A Prostitute Treating Herself for the Pox, c.1731. British Museum, Croft-Murray (unpublished) 10. ©Trustees of the British Museum.

Introduction

Illness was a frequent cause of poverty in eighteenth-century London, and the care of the sick formed a significant proportion of all poor relief expenditure. Many of the new associational charities of the century, such as the Lock Hospital, also cared for the sick, while London also inherited a significant number of older hospitals. Of these, the records of St Thomas's have been reproduced here. The role of the coroner in determining the cause of death in suspicious circumstances also required minute investigation of medical care and illness.

Although the average life expectancy in London through most of the eighteenth century was around forty, this was the result of cripplingly high infant and child mortality rates rather than adult mortality. If you survived to your teens, your life expectancy rose dramatically, but there was still plenty of ill health about.

The Parish

Illness formed both a powerful cause of real need, and a demonstrable circumstance that ensured the parish was obliged to provide relief. As a result, Overseers' Accounts (AC) frequently detail high levels of expenditure on medicine and nursing care. Particularly illuminating in this regard are the petty ledger accounts kept by St Dionis Backchurch, which over several decades organised expenditure records around individuals.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Churchwarden's Account Book, 1758 - 1762, 4222/1, LL ref: GLDBAC300070082.

London Metropolitan Archives, St Dionis Backchurch, Churchwarden's Account Book, 1758 - 1762, 4222/1, LL ref: GLDBAC300070082.

Workhouse Registers recording the admissions process, such as those for St Luke Chelsea and St Martin in the Fields, also list specific illnesses as the reason for entry in many cases - though it is important to note that these do not map onto modern illnesses in any clear and unproblematic way. Mortality rates for both infants and older paupers can also be calculated using these sources.

Infant and child mortality among the parish poor can also be researched using the Registers of Poor Children (RC) and Registers of Pauper Apprentices (RA) created as a result of Jonas Hanway's Acts of 1762 and 1767. For a more comprehensive source for the broad outline of illness in London, researchers should refer to the Bills of Mortality published once a month throughout the century, and relatively accurate through at least the 1750s. These detail how many people died of what cause, and in which parish. Unfortunately, we have been unable to included the Bills on this website.

Parish Vestry Minutes (MV) also include details of medical provision in both workhouses and through parish nurses, and occasionally specify a contractual relationship between the surgeon or apothecary who took on responsibility for the poor, usually in a workhouse, and the parish.

Hospitals

The only complete series of hospital records reproduced here are those from St Thomas's. These include the admissions registers (RH) for 1773-1800, which provide limited information about the medical condition of the patients, details of their ward (providing further evidence of the broad category of illness suffered), and precise information about who was paying for their care. Also reproduced on this site are the hospital's register of wounded seamen for the period 1672 to 1692, and register of deaths, 1763 to 1799. The three volumes of Hospital Letter Books (LB), 1704-1807, also contain information on the care of individuals and their medical circumstances, and on more general hospital policy. The hospital's Court of Governors Minutes (MG) and Grand Committee Minutes (MC) normally reflect deliberations about issues of policy, employment and the fabric of the hospital buildings rather than medical care per se.

Although Bridewell was jointly administered with Bethlem Hospital, or Bedlam, few references to the care of the mentally ill are included in the Bridewell records series posted here. A more promising source of information about the care of mental illness can be found in the Coroners' Inquests (IC). The Court Books (MG) of Bridewell itself do, however, contain occasional references to the physical health of the men and women incarcerated, and also some details of expenditure on medical care for them. The changing relationship between Bridewell and St Thomas's Hospital arising from the changing treatment of vagrants in the 1780s can also be traced in the Bridewell Court Books.

Coroners' Inquests

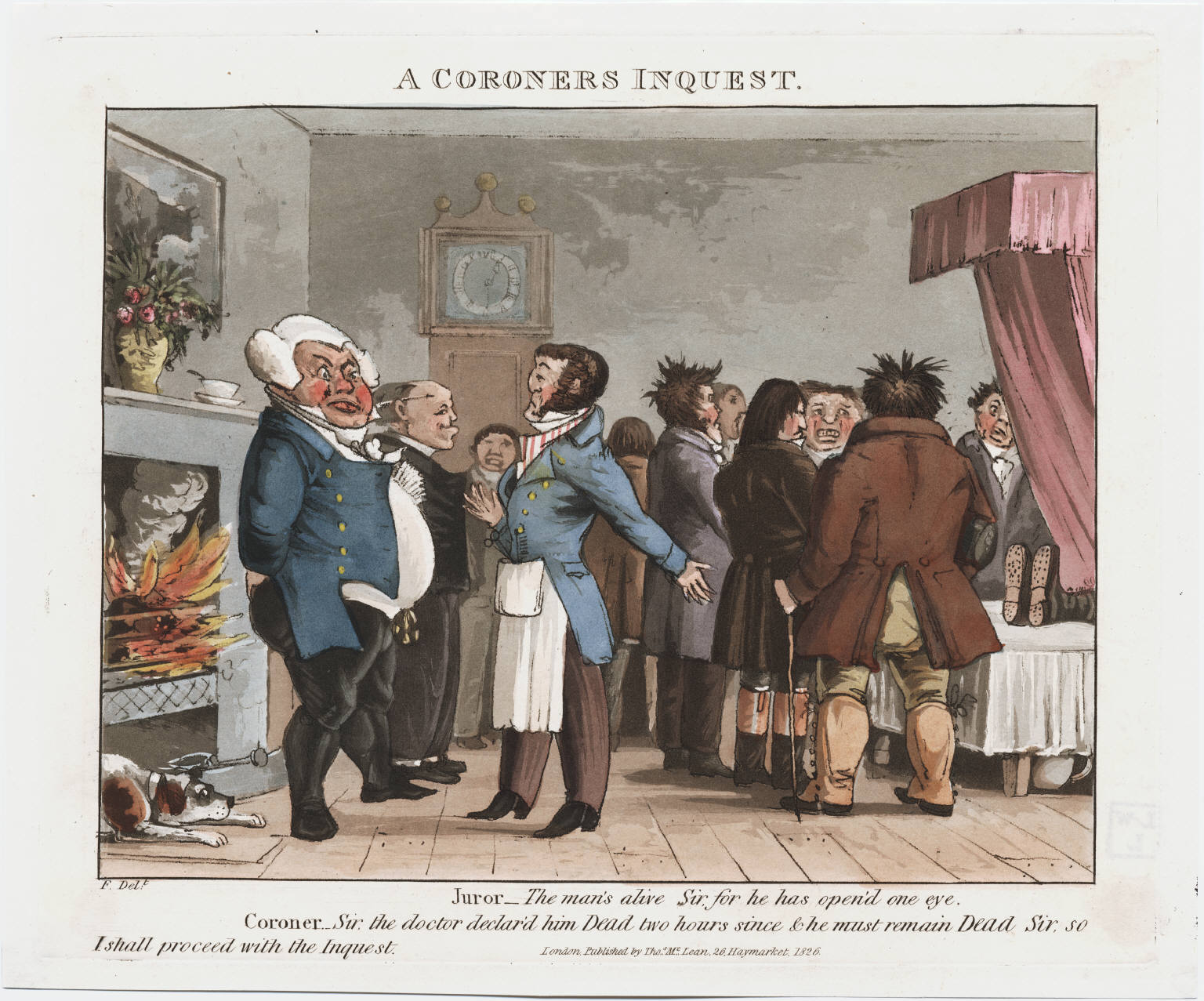

A Coroners Inquest, 1826. Lewis Walpole Library, 826.0.20. ©Lewis Walpole Library.

A Coroners Inquest, 1826. Lewis Walpole Library, 826.0.20. ©Lewis Walpole Library.

Coroners' Inquests (IC) detail the evidence gathered as part of an investigation into any suspicious or unusual death, and also the final conclusion of the coroner and his jury about whether a death was criminal. A substantial series of Coroners' Inquests for Westminster, covering the period 1760 to 1799, is included here, as well as a similar series covering the City of London and Southwark for the years 1789 to 1799. Both these series are remarkable for their inclusion in almost all instances of extensive depositional evidence recorded within hours of a death. This evidence frequently includes detailed accounts of the physical condition and medical treatment of the subject of the inquest prior to death, and forms a hitherto little studied source of data about the practice of medicine outside a formal institutional context. Because a substantial proportion of these inquests resulted a verdict of felo de se or suicide, they also contain a great deal of information about the impact and treatment of mental illness.

Legally, any death that occurred in prison was subject to a coroners' inquest. Prison inquests are spread throughout the Westminster and City series, and can also be found in the Sessions Papers (PS). Although these inquests tend to be less detailed than other London inquests, and very rarely resulted in a prosecution for murder, they do include information about the treatment of the physically ill in prison.

Coroners' inquests resulting in a charge of murder or manslaughter were removed from the normal series and passed to the grand jury, to determine whether a case should be brought against a named individual. These inquests are preserved in the Sessions Papers (PS), and if a prosecution resulted a record of the trial would be appear in the Old Bailey Proceedings. The Proceedings, in any case, contain large amounts of information related to issues of health and medical care, including frequent testimonies from surgeons, but have hitherto been little used by historians of medicine.

Questioning the Archive

- How did gender impact on the experience of illness and medical care?

- What was workhouse medicine like? Did it differ from medicine dispensed in the home or a hospital?

- How did the poor view their bodies - in illness and in health?

- What constituted health in the eighteenth century?

- How did prisoners and vagrants access medical care?

- How did the various medical institutions of London - workhouses, hospitals, charities - work together?

- Did disability exist?

- How were the mentally and physically ill treated by the criminal justice system?

- Did being ill change how the poor were viewed by their parish? Did it constitute a form of being deserving?

Back to Top | Introductory Reading

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the key phrase Ill-Health:

- Catherine Jones, fl. 1757-1783

- Charlotte Dionis, b. 1761

- Elizabeth Yexley, d. 1769

- George Barrington 1755-1804

- Mary Talbot, c. 1766-1791

- Michael Baker, b. 1682

- Repentance Hedges, d. 1730

- Richard Hedges, d. 1716

- Samuel Badham, 1692-1740

- Sarah Pilch fl. 1793-1818

- Sophia Pringle, c.1767-1787

- Timothy Dionis, 1704-1765

Lives using the keyword Insane:

Introductory Reading

- Landers, John. Death in the Metropolis: Studies in the Demographic History of London, 1670-1830. Cambridge, 1993.

- Levene, Alysa. Childcare, Health and Mortality at the London Foundling Hospital, 1741-1800: "Left to the mercy of the world". Manchester, 2007.

- Porter, Roy. Flesh in the Age of Reason: the Modern Foundations of Body and Soul. New York, 2004.

- Siena, Kevin. Venereal Disease, Hospitals and the Urban Poor: London's "Foul Wards," 1600-1800. Rochester (NY), 2004.

Online Resources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography.