Researching Crime

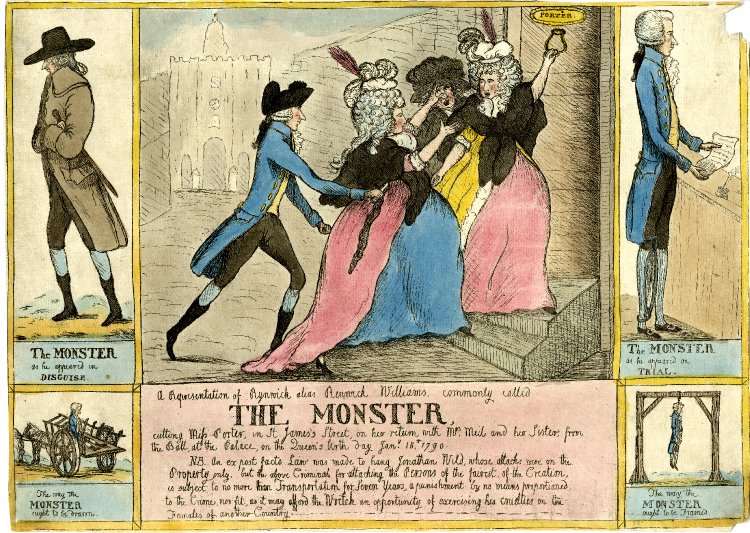

William Dent. A Representation of Rynwick alias Renwick Williams, Commonly Called the Monster. c.1790. British Museum, Satires 7730. © Trustees of the British Museum.

William Dent. A Representation of Rynwick alias Renwick Williams, Commonly Called the Monster. c.1790. British Museum, Satires 7730. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Introduction

London Lives includes a wide range of sources for the history of crime. In many cases, there are multiple records concerning individual prosecuted crimes. But it must be acknowledged that the vast majority of these documents were produced in order to record the processes of criminal justice, so evidence of actual crime must be derived by reading these records "against the grain". Nonetheless, London Lives allows users to link together the records of several different courts to trace individual criminal careers, or at least an individual's repeated encounters with the law, over a number of years. For examples of how the available sources can be used to write such stories, see the biographies of Edward Burnworth and Charlotte Walker in the Lives section. Where they exist, the Ordinary of Newgate's Accounts provide an excellent starting point for compiling criminal biographies.

For a comprehensive introduction to the criminal justice system which produced these records, see the Criminal Justice background pages.

Felonies

The most serious crimes, including treason, homicide, most forms of theft, forgery and coining, were labelled felonies. All such cases which occurred in the metropolis north of the River Thames were tried in a single court, the Old Bailey. This website includes all surviving copies of the Old Bailey Proceedings, printed accounts of trials held at the Old Bailey, as well as pre-trial examinations and depositions for these cases kept in the Sessions Papers (PS). (For the period before 1755, these are with the City, Middlesex and Westminster sessions papers [SLPS, SMPS, and WJPS], and from 1755 they are in the separate OBPS series.) The sessions papers also include some correspondence relating to procedural issues. Although sessions papers do not survive for every case, where they do exist they can provide valuable additional evidence not found in the printed account of a trial.

Two other record types which provide information about those accused of felonies are the richly detailed Ordinary's Accounts (OA), biographies of the convicts executed at Tyburn, and, from 1791, the Criminal Registers (CR), lists of prisoners in Newgate Prison. Both include some details not found in the Old Bailey Proceedings. Documents related to killings which did not result in a criminal prosecution, either because the alleged culprit was not found or because a decision was taken not to prosecute, can be found in the Coroners' Inquests (IC). These cases can shed light on the notorious dark figure of unrecorded (or unprosecuted) crime, with respect to violence.

For listings of many sources related to Old Bailey trials, including printed criminal biographies, which are not included in London Lives, see the Associated Records Database.

Watch House, Covent Garden. c.1835. © The Museum of London

Watch House, Covent Garden. c.1835. © The Museum of London

Misdemeanours

This category of petty crimes encompasses a huge range of offences whose only unifying characteristics are the facts they were tried in the criminal courts and were not felonies. They include offences against the peace (such as riot and assault), petty theft (of goods worth less than one shilling), prostitution and vagrancy, offences relating to the misbehaviour of apprentices or mistreatment by their masters, and a wide range of nuisance and regulatory offences (such as keeping a disorderly alehouse and failing to serve on the night watch).

The records of prosecutions of these crimes are less detailed than those for felonies, and fewer have been included on this website. Arguably the most comprehensive records of misdemeanour prosecutions available are those of the City of London's magistrate's courts, but the descriptions of offences in these records are very limited and they have not been included. These, and most of the other records of criminal prosecutions not included on this site, can be found at the London Metropolitan Archives (LMA).

The two most important documents concerning petty crimes included in London Lives are the sessions papers and the records of commitments to houses of correction.

For those tried at the sessions of the peace, the Sessions Papers (PS) are less useful than in the case of felonies, and include few depositions and examinations. The most relevant documents in this record series are occasional petitions and other correspondence with the court and calendars of recognizances, indictments, and prisoners (these rarely, however, provide details of the offence). For actual records of the trials, including indictment rolls and registers which document judicial decisions, it is necessary to consult the manuscripts held in the LMA.

For those accused of petty crimes who were committed to houses of correction, primarily the poor who were charged with idle and disorderly conduct, vagrancy, prostitution, and petty theft, London Lives includes the records of Bridewell, the house of correction for the City of London. Calendars of prisoners in the Middlesex and Westminster houses of correction can be found in the Sessions Papers, but these typically only list names. All these records only document the prisoners who happen to have been in the house of correction at the time the records were compiled (typically when the court met). Turnover calendars, which document every prisoner committed, survive erratically in manuscript series not included in London Lives. These too can be found in the LMA.

Questioning the Archive

For the historian of crime, the biggest challenge is to go beyond the records of criminal prosecutions to study the nature and causes of 'crime itself. Since most existing scholarship is focused on the judicial system, there is still a lot of work to do. Among the questions worth asking, and for which this website can be used to find some answers, are:

- Was poverty a primary cause of crime?

- Were those who were denied access to poor relief likely to commit theft instead?

- Why did people resort to violence, and why did the amount of violence decrease over the course of the eighteenth century?

- Was participation in certain forms of employment likely to lead to participation in crime?

- Did criminals often act in groups, or form gangs?

- Did many people engage in crime on a regular basis, as a profession or career?

- Did participation in petty crime, such as petty theft and prostitution, frequently lead to engagement in more serious forms of crime, including violence and more substantial thefts?

- Did those who were convicted and punished for felonies frequently commit further crimes? Why?

- How did patterns of male and female criminality differ?

- How much evidence is there in the records of prosecuted crime about crimes which were not prosecuted, and does this suggest that studying the history of crime through records of criminal prosecutions leads to a distorted picture?

- What sorts of people were most likely to become victims of crime?

- Did the victims of violent crimes often end up in hospitals?

- Did victims of crime ever go on to commit crimes themselves?

Back to Top | Introductory Reading

Exemplary Lives

Lives using the keyword Infanticide:

Lives using the keyword Murder:

- Daniel Vaughan, c. 1692-1716

- Edward Burnworth alias Frazier, d. 1726

- Edward Kirk, fl. 1684

- Francis David Stirn, 1735-1760

- George Lovell, alias Gypsy George, c. 1742-1772

- James Carse, b. 1758

- James Cluff, c. 1698-1729

- John Gower, c. 1658-1684

- Joyce Hodgkins, c. 1672-1714

- Louis Houssart, c. 1684-1724

- Mabel Hughes c.1678-1755

- Samuel Badham, 1692-1740

- Sarah Malcolm, 1710-1733

- William Blewit d. 1726

Lives using the keyword Prostitute:

Lives using the keyword Burglary:

- Ann Somerville, fl. 1790-1796

- Christopher Leonard, fl. 1721-1726

- Garret Lawler, 1725-1751

- John Page fl. 1742-1757

- John Trantum or Trantrum, 1701-1721

- Mary Nichols, alias Trolly Lolly, c. 1685-1715

- Richard Trantum or Trantham, 1698-1723

- Sarah Malcolm, 1710-1733

- Shadrach Guy, c. 1693-1715

- William Tidd, c. 1729-50

Lives using the keywordsHighway Robbery:

Lives using the keyword Pickpocket:

Introductory Reading

- Beattie, J. M. Crime and the Courts in England 1660-1800. Princeton, 1986.

- Clayton, Mary. The Life and Times of Charlotte Walker, Prostitute and Pickpocket. London Journal, 33 (2008), pp. 3-19.

- Henderson, Tony. Disorderly Women in Eighteenth-Century England. Harlow, 1999.

- King, Peter. Crime, Justice and Discretion in England, 1740-1820. Oxford, 2000.

- Linebaugh, Peter. The London Hanged: Crime and Civil Society in the Eighteenth Century. 1991.

- MacKay, Lynn. Why they Stole: Women in the Old Bailey, 1779-1789. Journal of Social History, 32 (1999), pp. 623-40.

- Shoemaker, Robert B. Using Quarter Sessions Records as Evidence for the Study of Crime and Criminal Justice. Archives, 20 (1993), pp. 145-57.

- Shoemaker, Robert B. The London Mob: Violence and Disorder in Eighteenth-Century England. 2004.

Online Sources

For further reading on this subject see the London Lives Bibliography